Beyond money

Fabio Panetta is Governor of the Bank of Italy

The euro itself was launched 25 years ago, in January 1999, and at the end of that year Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, Slovakia, Bulgaria and Malta were invited to start negotiations to join the European Union (EU)1. These events are all part of a single, coherent historical process, driven by the integration project that Europe undertook in the post-war period.

The Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) is one of the most ambitious elements of this project, and the euro is both a key achievement and a powerful symbol of success. Given my role and background, you might expect me to talk about the euro from a purely monetary perspective.

However, I will not do that. Finance is a means to serve society, and the euro is no exception: the single currency has objectives and implications that go far beyond the monetary sphere. Its fate shapes Europe’s role in the global economic and financial landscape.

Its function as an international reserve currency affects Europe’s strategic autonomy and geopolitical position. From the perspective of 2024, the relevance of these issues can hardly be overstated. My remarks are structured around three broad themes.

First, why we care about the international role of the euro (IRE), second, how this role has evolved over time, and third, what we can do to strengthen it.

1. Why do we care about the international role of the euro?

Before February 2022, most people would have answered this question in purely economic terms. Issuing a currency that is widely used internationally for commercial and financial transactions brings both benefits and risks to an economy.

It is crucial for a central bank to consider these factors in order to achieve its price stability objective and preserve financial stability. Let me summarize them. Before the global financial crisis, the benefits were traditionally considered to be threefold.

First, high seigniorage for the central bank, and ultimately for the taxpayers of the issuing country2. Second, a reduction in transaction and hedging costs for users of the currency. Third, the ‘exorbitant privilege’3: as long as there is strong global demand for safe assets, an economy issuing a reserve currency enjoys lower funding costs than its peers and hence it earns a positive return on its net foreign asset position4.

The main risks were associated with higher volatility in monetary aggregates and capital flows due to exogenous shifts in demand and risk appetite. The global financial crisis prompted a re-examination of these issues.

On the one hand, we realized that the ‘exorbitant privilege’ could become an ‘exorbitant duty’ at times of international stress, when the dominant economy unwillingly becomes a global bank and experiences a sharp exchange rate appreciation5.

On the other hand, we learned that an international reserve currency reduces the pass-through of exchange rate shocks to domestic inflation, making foreign exchange volatility less of a concern, and that, in a financially integrated world, it can make monetary policy more powerful by generating positive spillovers and spillbacks6.

All in all, the macroeconomic benefits of issuing a reserve currency should largely outweigh the risks7. The estimates obtained from US data are instructive in this respect. Research shows that the US Treasury historically issued long-term bonds at a discount of 30 to 70 basis points relative to private securities with comparable characteristics, generating seigniorage revenues of the same magnitude as those obtained by the Federal Reserve from the monetary base.

For the euro area, assuming a hypothetical 50 basis points discount, seigniorage could in principle generate a revenue of ½ percentage point of GDP per year8. These numbers are purely indicative, but they may give us an idea of the magnitude of the potential gains9.

More importantly, Russia’s aggression against Ukraine was a stark reminder that these monetary benefits only tell (at best) half the story: the other half has more to do with politics than monetary economics. In a politically volatile world, a country that issues an international currency is less exposed to financial pressures from other (possibly hostile) nations.

The reason for this is that its financial and payment flows do not require the use of other currencies. In and of itself, an international currency is a pillar of the issuer’s ‘strategic autonomy’. It acts as an insurance policy – a function that may seem worthless in normal times but becomes very valuable in bad times.

Europeans are fully appreciating its value today. The issuer of a global currency can use its financial power to influence international developments. This power must be used wisely, however, because international relations are part of a ‘repeated game’: weaponizing a currency inevitably reduces its attractiveness and encourages the emergence of alternatives.

A scarce supply of safe euro-denominated assets is perhaps the single most important constraint on the CMU, and hence on the global reach of the euro

The case of the renminbi is instructive in this respect. The Chinese authorities are explicitly promoting its role on the global stage and encouraging its use in other countries, including those sanctioned by the international community following the invasion of Ukraine.

Most of Russia’s imports from China, as well as some of its oil shipments to China, are now invoiced in renminbi10, and the share of Chinese trade settled in renminbi has doubled over the past three years11. As a result, at the end of 2023, the renminbi overtook the euro as the second most used currency for trade finance12 and the yen as the fourth most used currency for global payments13.

There is little evidence so far that political fragmentation is systematically translating into currency fragmentation14, but we should be alert to the possibility that politics will have a greater impact on international currencies in the coming years. And, of course, vice versa.

2. The performance of the euro since its launch

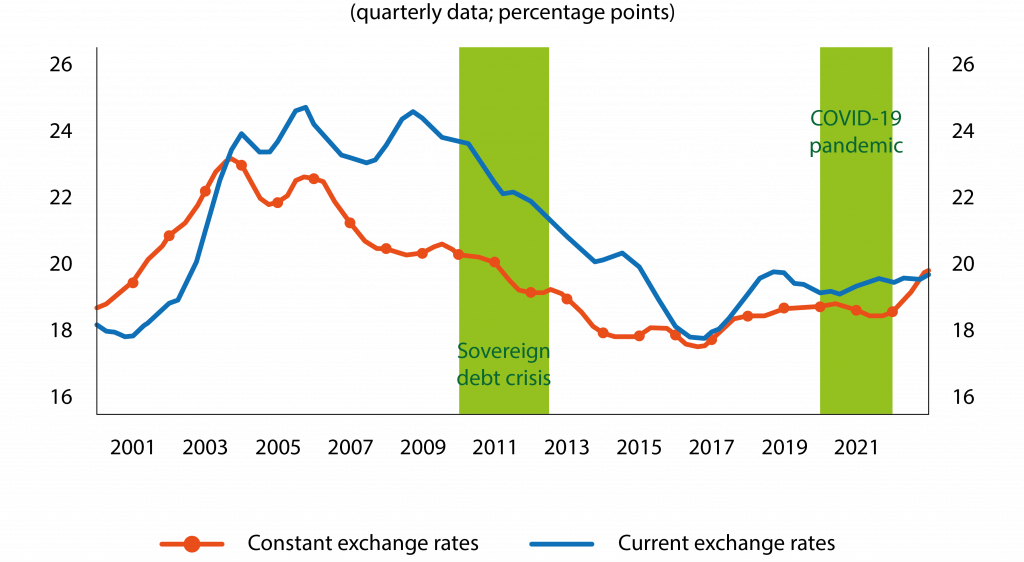

How has the euro performed over its 25-year journey? Between 1999 and 2022, the euro’s share in global portfolios fluctuated between 17 and 25 per cent (Figure 1)15. The dominance of the US dollar has remained unchallenged. In terms of foreign exchange reserves, for example, the euro accounts for 20 per cent of the total, while the share of the US dollar is three times as high and has only recently fallen below 60 per cent.

Figure 1. ECB Composite Index of the International Role of the Euro (1)

(1) Four-quarter moving average, at current and constant Q4 2022 exchange rates. Arithmetic average of the shares of the euro in stocks of international bonds, loans by banks outside the euro area to borrowers outside the euro area, deposits with banks outside the euro area from creditors outside the euro area, global foreign exchange settlements, global foreign exchange reserves and global exchange rate regimes. See ECB (2023).

Source: ECB.

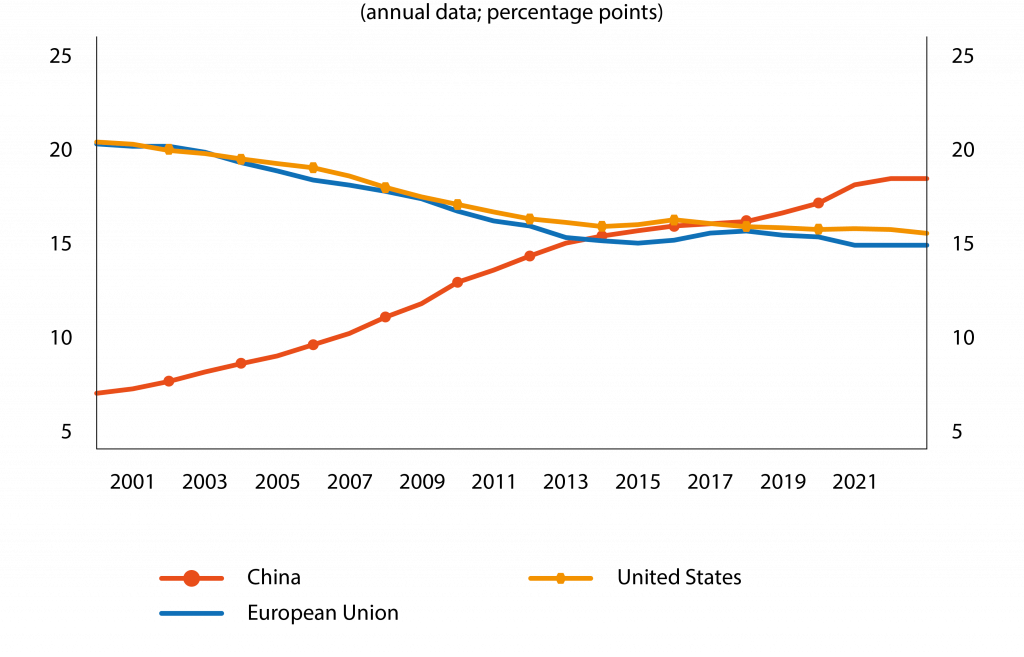

Given the size of the underlying economies, one might think that the euro is ‘punching below its weight’16. After all, the US and European economies are about the same size (Figure 2). A closer look at the data sheds light on why the euro failed to gain more ground in global markets.

The share of the euro declined significantly during the financial and sovereign debt crisis, between 2009 and 2015, when the euro area was hit by asymmetric shocks that were met with inadequate policy responses. During this phase, fiscal policies supported the economy for a short time but then turned into procyclical fiscal consolidation. Interventions were uncoordinated and inconsistent with the appropriate fiscal stance at European level.

Figure 2. GDP based on purchasing power parity (1)

(1) Share of world GDP.

Source: IMF, World Economic Outlook, October 2023.

As a result, a fault line emerged between a ‘core’ and a ‘periphery’, leading to deep economic, social and political divisions. Investors believed that the euro area could break up under pressure.

Unsurprisingly, procyclical policies and conflicting messages from policymakers did little to reassure them. It was President Draghi’s ‘whatever it takes’ statement that turned the tide in financial markets, making it clear to everyone that the euro would weather the storm17.

Now let’s fast-forward to more recent times. Between 2020 and 2022, Europe was hit by a series of large and persistent supply shocks. The pandemic and the invasion of Ukraine depressed economic activity and caused a rise in uncertainty that was in many ways more significant than that experienced a decade earlier.

These shocks also clogged production lines, and dramatically disrupted trade flows. However, this time round they hit an institutional system that was better equipped to deal with them.

Moreover, they were countered by a mix of strong and coherent policy responses at both European and national level. As a result, they had no impact on the IRE: the euro held its ground, and by some measures even strengthened during this period.

It is risky to draw general conclusions from a few observations. However, it seems clear to me that both the nature of the shocks and the policy responses were crucial in these episodes. The euro area is vulnerable to shocks that fragment its economy and financial markets along national lines; the problems are exacerbated when coordination problems hamper or even impede an effective policy response.

Yet Europe can easily withstand large shocks, as long as it sticks together and responds quickly and decisively with appropriate policies. While it may still be true that Europe ‘will be forged in crises’, as Jean Monnet famously declared18, it is also true that not all crises are equal and not all responses are the same.

3. Enhancing the international role of the euro

So, how can we promote the IRE? The creation of a global currency is a complex phenomenon that requires many ingredients. Economic size is certainly essential, but not sufficient. Three other factors come to mind.

3.1 The policy mix

The first and most obvious ingredient is macroeconomic stability. When foreign investors buy euro-denominated assets, they are effectively buying a stake in our economy. The dividend they expect is economic growth and low and stable inflation, and the only way to guarantee this dividend is to implement credible, effective and countercyclical macroeconomic policies.

Even a structurally sound country would struggle to maintain its global role if it lurched from one recession to the next, or experienced frequent bouts of inflation or deflation. This means that getting the ‘policy mix’ right is of paramount importance.

The Great Moderation is now a fading memory, and there is a good chance that Europe will again face situations that require a joint European monetary and fiscal response. The pandemic provides a template for how these situations should be managed; the sovereign debt crisis arguably provides a template for how they should not be managed.

3.2 Capital markets

The second key ingredient is a better meeting place for savers and borrowers. To retain domestic investment and attract resources from abroad, Europe needs liquid and integrated capital markets.

This was the idea behind the Capital Markets Union (CMU) initiative launched by the European Commission in 2015, as well as the Commission’s Action Plan of 2020. The CMU could play a key role in diversifying the financing of EU companies, in strengthening private risk sharing and in providing better investment opportunities for domestic and foreign savers.

However, capital markets in Europe are still underdeveloped compared with those in other major advanced economies. Despite efforts to harmonize rules and integrate national markets through the implementation of European legislation, progress towards a single European market has been limited.

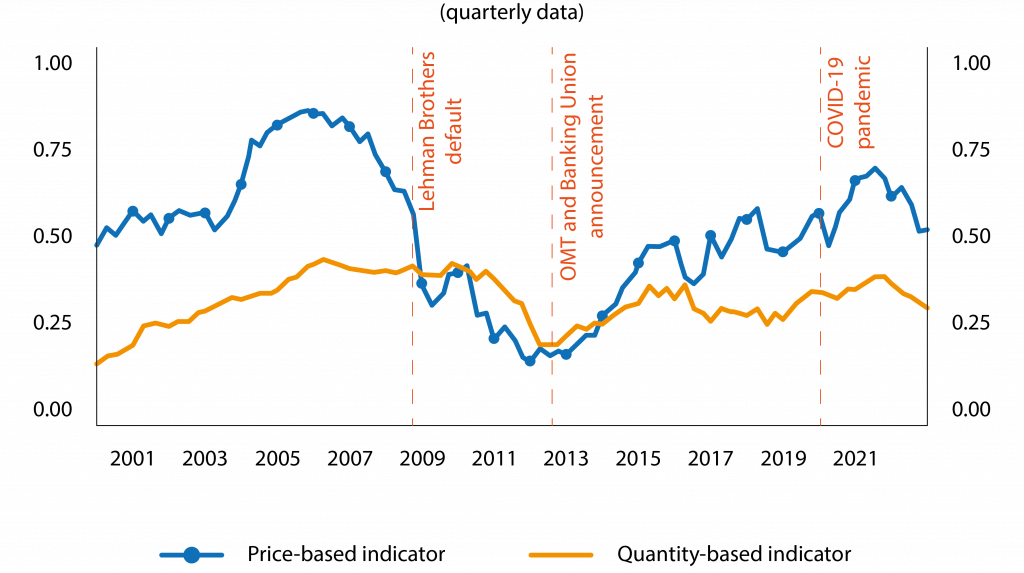

Over the past 25 years, financial integration has followed roughly the same path as the IRE (Figure 3). After rising steadily in the early 2000s, it fell to a minimum in the sovereign debt crisis. The positive trend resumed in 2012, following the announcements of the establishment of the Banking Union and the ECB’s Outright Monetary Transactions and, apart from a temporary dip in 2020, integration maintained its momentum throughout the COVID pandemic.

Figure 3. Financial integration composite indicators (1)

(1) The price-based composite indicator aggregates ten indicators for money, bond, equity and retail banking markets; the quantity-based composite indicator aggregates five indicators for the same market segments except retail banking. Both indicators measure integration on a scale from zero (no integration) to one (perfect integration). See Financial Integration and Structure in the Euro Area, ECB Committee on Financial Integration, April 2022.

Source: ECB.

This is no coincidence: it indicates that the global relevance of the euro goes hand in hand with the degree of financial integration within the EMU. The data also show that, after these ups and downs, European markets are about as integrated today as they were in 2003-2004. I dare say that this result falls short of the European Commission’s initial aspirations19.

How can we do better? I will not bore you with a detailed review of the CMU, but I would like to mention two issues that I consider critical from the perspective of a ‘global euro’. The first problem is the lack of a European safe asset. The availability of a common risk-free benchmark is necessary for critical financial activities.

It would facilitate the pricing of risky financial products such as corporate bonds or derivatives, thereby stimulating their development. It would provide a common form of collateral for use in centralized clearing activities and crossborder collateralized trading in interbank markets.

It would help diversify the exposures of both banks and non-banks. It would form the basis of the euro-denominated reserves held by foreign central banks. And the list goes on.

A scarce supply of safe euro-denominated assets is perhaps the single most important constraint on the CMU, and hence on the global reach of the euro20.

The issuance of the Next Generation EU bonds is a first and welcome step in this direction, but a one-off programme is not a game changer: to stimulate the development of the CMU and strengthen the IRE, we would need a steady, predictable supply of ‘safe assets’.

The second problem is that we do not have a fully-fledged banking union (yet). The creation of a Single Supervisory Mechanism and a Single Resolution Mechanism after the financial crisis was a quantum leap in this respect, but it was not sufficient to create a single banking market.

The European banking sector remains largely segmented along national lines: in 2021, banks held domestic assets worth more than four times the value of their non-domestic euro-area assets21. This poses a problem for the creation of a genuine CMU, as banks play a central role in all the major financial centres.

They operate – and often lead – in key segments such as asset management, bond underwriting and initial public offerings, they provide financial advice and they trade actively in securities markets, often providing critical market-making services. It is therefore difficult to imagine a genuine CMU without banks that are able to operate smoothly throughout the euro area. Improving in these dimensions is as important as ever.

In the coming years, Europe may have to navigate a more challenging global political environment than in the past. It will also have to deliver on its ambitions in areas such as defence and the green and digital transitions. As I have argued elsewhere, a fully functioning CMU would greatly enhance its chances of success22.

3.3 Payment systems and market infrastructure

The third component is payment and market infrastructures fit for the 21st century. These are an essential part of the ‘plumbing’ of the financial system.

Digitalization is clearly the defining challenge of our time: it is a profoundly transformative process that is already having a vast and complex impact on society. Payments are no exception to this trend: demand for digital payment services has grown markedly around the world, especially in the aftermath of the COVID pandemic23.

In this landscape, a central bank digital currency (CBDC) can play an important role24. The good news is that Europe is in many ways at the forefront of the progress in this area. Many will be familiar with the digital euro, the retail CBDC that is being considered by the Eurosystem.

In addition to making life easier for European citizens, a digital euro would offer great opportunities at international level if it could be made available outside the euro area or used for cross-currency payments25.

The same applies to a wholesale CBDC. Unlike the retail version, this is already a reality: the TARGET infrastructure operated by the Eurosystem, which allows banks to settle euro-denominated digital transactions in central bank money via a central ledger, has been operating successfully for decades26.

Building on this experience, the Eurosystem is now exploring new solutions based on distributed ledger technology (DLT), and how these could interact with the existing TARGET infrastructure27. Digital central bank money is not the only game in town: many other initiatives have been launched to modernize and enhance the EU’s infrastructures.

These include, for instance: (i) promoting the linking of TIPS (the euro area’s Target Instant Payment Settlement mechanism) with fast payment systems in other countries28; (ii) developing the Eurosystem Collateral Management System29; (iii) adopting the new EU Regulation on Markets in Crypto Assets (MiCA) to regulate the cryptoasset ecosystem30; (iv) adopting the Eurosystem’s Cyber-resilience strategy for Financial Market Infrastructures31; and (v) revising the European Market Infrastructure Regulation (EMIR) to support the growth and resilience of European clearing services and reduce reliance on third-country central counterparties32.

As well as supporting the IRE, these developments will give a much-needed boost to global crossborder payments, which are currently expensive, sluggish and not very inclusive33.

4. Conclusions

Before I conclude, let me step back from the technicalities and take a look at the big picture. The rise and fall of global currencies is often seen as a structural process that unfolds slowly and smoothly over time.

History tells us otherwise: in the last century, the dollar overtook sterling as the main invoicing currency in the immediate aftermath of the First World War and equalled its share of global bond issuance around 1929.

However, its rise reversed sharply with the Great Depression, and the two currencies coexisted at the apex of a bipolar monetary system until the 1950s. In short, the making – or unmaking – of an international currency is not only complex, but also volatile, non-linear and less predictable than most people think.

This means that the IRE is not set in stone. Over the next decades, the euro could maintain its role, be relegated to the periphery of the global monetary system, or gain a stronger position at its centre. A combination of factors is needed to strengthen its role.

We need effective macroeconomic policies that deliver macroeconomic stability; a fully-fledged banking and capital market union; and dynamic, future-proof payments and market infrastructures.

The common thread behind these initiatives is that they all reinforce the integration process; they would allow us to build on our past achievements and take the EMU a step closer to a truly integrated monetary, fiscal and political union.

The recipe may seem difficult to implement, but it is what Europe’s citizens expect of their governing institutions: the IRE is just another good reason not to let them down. The stakes are high, because the euro is the keystone of the EMU, and the EMU is much more than just an economic arrangement: it reflects the dedication of its members to European unification.

In times of geopolitical tensions, it also functions as a collective defence clause: any attack against a member affects the single currency, a crucial aspect of our shared sovereignty, and is consequently an attack against the entire Union34.

The EMU is the vehicle that generations of Europeans have built to pursue peace, freedom and prosperity together. It embodies their desire to walk and work together on the world stage. As such, it deserves our unwavering support.

Endnotes

1. At the Helsinki summit in December 1999, the European Council decided to convene bilateral conferences to begin negotiations with Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, Slovakia, Bulgaria and Malta.

2. Seigniorage is the profit made by a central bank (and hence by a government) by issuing currency. This profit can be very significant when a currency is widely used internationally.

3. The expression ‘exorbitant privilege’ was created by Valéry Giscard d’Estaing in the 1960s with reference to the advantages that the United States has due to the US dollar’s role as the global reserve currency.

4. ECB, 2019, The international role of the euro; Gourinchas, Rey and Sauzet, 2019, The international monetary and financial system, Annual Review of Economics 11, 859-893.

5. Rey, 2019, International monetary systems and global financial cycles, Bank of Italy Baffi Lecture on Money and Finance.

6. ECB, 2019, cited.

7. See eg. Cova P, Pagano P and Pisani M (2016), ‘Foreign exchange reserve diversification and the “exorbitant privilege”: global macroeconomic effects’, Journal of International Money and Finance, 67, 82-101.

8. The estimate for the US is taken from Krishnamurthy A, and Annette Vissing-Jorgensen, A (2012), ‘The aggregate demand for Treasury debt’, Journal of Political Economy, 120 (2), 233-267. The paper shows that the discount depends on the debt-to-GDP ratio and is lower when debt is high (implying an ample supply of government bonds). Based on an average debt-to-GDP ratio of about 44 per cent in the pre-2008 data, the authors estimate an average discount of 53 basis points and a seigniorage revenue of 0.23 per cent of GDP. The euro area calculation reported in the text assumes similar debt demand curves for the US and a hypothetical euro area debt issuer, which is clearly a simplification. We apply the discount to the euro area debt-to-GDP ratio observed at the end of 2022, which was 91 per cent.

9. Financial markets provide another perspective on this issue. Bond purchases by central banks, finance ministries and sovereign wealth funds have a large impact on yields: a $100 billion purchase can reduce the 10-year Treasury yield by 50 basis points over a one-year horizon (see Ahmed, R, and Rebucci, A, 2022, ‘Dollar reserves and US yields: Identifying the price impact of official flows’, National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper no. 30476). At the end of 2022, global foreign exchange reserves amounted to €11.4 trillion, of which 80 per cent (around 9.1 trillion) were in currencies other than the euro. Based on the above estimate, and assuming euro- and dollar-denominated bond markets to behave in the same way, a shift of 1% of these reserves (0.9 trillion euros) into euro-denominated bonds could reduce European yields by 45 basis points.

10. Wall Street Journal, ‘How China manages its currency, and why that matters’, 2 January 2024. The share increased from 13 per cent to about 25 per cent between 2020 and 2023.

11. Wall Street Journal, ‘China’s Yuan is quietly gaining ground’, 27 December 2023.

12. After the dollar. See Financial Times, ‘China’s renminbi pips Japanese yen to rank fourth in global payments’, 21 December 2023. The ranking is based on the currencies’ shares in the payments settled through the Swift platform.

13. After the dollar, euro and sterling.

14. See eg. ECB, 2023, The international role of the euro.

15. The figures are based on the composite indicator employed in the ECB (2023). The indicator is the arithmetic average of the shares of the euro in stocks of international bonds, loans by banks outside the euro area to borrowers outside the euro area, deposits with banks outside the euro area from creditors outside the euro area, global foreign exchange settlements, global foreign exchange reserves and global exchange rate regimes.

16. Ilzetzki, E, Reinhart, CM and Rogoff, KS (2020), ‘Why is the euro punching below its weight?’, Economic Policy, 35(103), 405-460.

17 Panetta F, ‘Europe’s shared destiny, economics and the law’, Lectio Magistralis on the occasion of the conferral of an honorary degree in Law by the University of Cassino and Southern Lazio, 6 April 2022.

18. Monnet, J (1978), Memoirs, Collins, London.

19. Medium-term trends show that access to market-based finance for companies has deteriorated, the amount of loans transformed into market instruments such as securitization has fallen significantly, intra-EU integration has deteriorated slightly, while the amount of household wealth in the form of securities has shown little progress, AFME, ‘Capital Markets Union. Key Performance Indicators – Sixth Edition’, November 2023.

20. Ilzetzki et al (2020), cited.

21. Enria (2021), ‘How can we make the most of an incomplete banking union?’ Speech at the Eurofi Financial Forum, Ljubljana, 9 September 2021.

22. See Panetta F (2023), ‘Europe needs to think bigger to build its capital markets union’, Politico, 30 August 2023, and Panetta F (2023), ‘United we stand: European integration as a response to global fragmentation’, speech delivered at a Bruegel meeting on ‘Integration, multilateralism and sovereignty’, Brussels.

23. Glowka, M, Kosse, A and Szemere, R, (2023) ‘Digital payments make gains but cash remains’, CPMI Brief No 1.

24. Panetta, F and Dombrovskis, V (2023), ‘Why Europe needs a digital euro’, ECB Blog, 28 June 2023.

25. The ECB and the euro area National Central Banks are exploring options for using CBDCs to make cross-currency payments faster, cheaper, more transparent and more inclusive. See CPMI, BISIH, IMF, WB (2022), Options for access to and interoperability of CBDCs for crossborder payments.

26. Panetta, F (2022), ‘Demystifying wholesale central bank digital currency’, speech at the Symposium on ‘Payments and Securities Settlement in Europe – today and tomorrow’, hosted by the Deutsche Bundesbank, 26 September 2022.

27. The exploration involves trials and experiments to create a ‘technological bridge’ between the central bank’s currency settlement system and the external private DLT platforms that manage tokenized digital assets. The tests have been conducted independently so far by Banca d’Italia, Banque de France and the Bundesbank. See H Neuhaus and M Plooij, ‘Central bank money settlement of wholesale transactions in the face of technological innovation’, published as part of the ECB Economic Bulletin, Issue 8/2023.

28. Tests have been successfully carried out on the connection of the instant payment systems of the Eurosystem, Malaysia, and Singapore, using the Bank for International Settlements Project Nexus model. A Proof of Concept was successfully executed between TIPS and Buna, the crossborder and multi-currency payment platform for the Arab region.

29. The Eurosystem Collateral Management System (ECMS) is a unified system for managing assets used as collateral in Eurosystem credit operations. Together with the other TARGET Services offered by the Eurosystem, the ECMS will ensure that cash, securities and collateral flow freely across Europe.

30. MiCA aims to regulate the issuance, offer to the public, admission to trading and provision of services relating to digital representations of rights and value based on DLTs, defined as cryptoassets.

31. The strategy is based on three pillars: (i) fostering the readiness of financial entities by providing a range of tools to assess euro-area payment systems and financial infrastructures; (ii) strengthening the resilience of the financial sector as a whole, by implementing market-wide business continuity exercises; and (iii) enhancing cooperation and information sharing on cyber threats among the major financial entities through the establishment of the Euro Cyber Resilience Board for Pan-European Financial Infrastructures.

32. One of the main measures proposed by the European Commission is that all the relevant market participants would be required to hold active accounts with European CCPs. Other proposed measures are meant to strengthen the existing supervisory framework for EU CCPs. See EUR-Lex – 52022PC0697 – EN – EUR-Lex (europa.eu).

33. Panetta F (2023), ‘The world needs a better crossborder payments network’, Financial Times, 31 October 2023.

34. Article 42(7) of the Treaty on European Union states that ‘If a member state is the victim of armed aggression on its territory, the other member states shall have towards it an obligation of aid and assistance by all the means in their power, in accordance with Article 51 of the United Nations Charter’. This principle was recalled by the EU Heads of State and Government in the Versailles Declaration of 10 and 11 March 2022.

This article is based on an address delivered at the Conference Ten years with the euro, Riga, 26 January 2024.