Accelerating strategic investment in the EU

Maria Demertzis is a Senior Fellow at Bruegel and Professor at the Florence School of Transnational Governance, EUI, David Pinkus is an Affiliate Fellow at Bruegel and Affiliated Researcher at Copenhagen Business School, and Nina Ruer is a Research Intern at Bruegel

Executive summary

The European Union’s ability to meet its long-term objectives – primarily managing the climate and digital transitions and achieving greater economic resilience – will depend crucially on how much it invests and what it invests in.

For the two transitions, the EU member states collectively face a total annual investment gap of at least €481 billion up to 2030. Closing this gap, which is necessary if the EU is to achieve its strategic objectives, will rely on the efficient use of public resources and on mobilising private investment.

We discuss a potential long-term EU approach to the financing of strategic objectives. We define the notion of strategic investment in the context of the EU, set conditions for such investment to be (co-) financed at EU-level, and make recommendations about strategic investment in the EU beyond 2026.

We argue that EU (co-)finance would be justified if there is demonstrable EU value added, for example in the form of crossborder efficiency gains. The term ‘strategic’ would help prioritise how the EU pursues its economic and security interests.

Examples that would qualify as European strategic investments include energy and connectivity infrastructure with crossborder impact, and facilities that boost innovation and promote economic security and resilience at the EU level.

We examine various past and present EU strategic project financing programmes. We also survey national programmes to identify best practices in public investment management. We make the following main policy recommendations:

1. There is a lack of continuity in the way that the EU has pursued investments in that programmes have been finite and sporadic, with different sources of funding and overlapping objectives. We propose the creation of a dedicated and permanent fund for European Strategic Investments (ESIs), that can come in the first instance from a partly repurposed European budget (the Multiannual Financial Framework).

2. We argue that the European Investment Bank (EIB) would be the natural manager of such a fund. The fund itself should employ all the financial instruments at its disposal to finance projects. Projects should be evaluated in terms of how well they provide European added value and contribute to the EU’s strategic objectives.

3. Beyond current financing means, the EU still needs to make progress on establishing new own resources, or revenues for the EU budget, to repay debt issued under the NextGenerationEU post-pandemic recovery instrument. At a later stage, a consequence of having established new own resources will be that the EU will then have additional dedicated financing streams that it could use for ESIs. This would ensure continuity in pursuing strategic objectives.

1 Introduction

The European Union’s ability to meet its long-term objectives, from managing the twin transitions (climate and digital) to greater economic resilience, and from security to promoting multilateralism, will depend crucially on how much it invests and in what.

The huge investment that has been identified as a prerequisite to move forward on some of these objectives will require the participation of the private sector and public authorities alike.

In this study, we explore the EU’s role, beyond that of member states, in financing directly some of the strategically relevant projects.

A major objective for the EU economy is to remain competitive globally, without resorting to protectionist measures that go against the multilateral system.

A necessary ingredient to remaining competitive in a world of big players is to increase and maintain scale. Deepening and expanding the EU single market for goods and services are ways of promoting scale. European economies still operate with a considerable home bias that favours domestic firms over those that may reside even just over the border.

A bigger and deeper single market for goods and services is necessary for developing big firms that can compete globally, and for creating conditions for innovation and ensuring dynamism in the labour force.

Finance should play an important role in deepening the single market but when it comes to financial inter-mediation, there are no unified markets for banks and capital across the EU. Despite the creation of a banking union, banks still operate predominantly within national borders. Making progress with completing the banking union would help move in the direction of a unified market that would increase the financing capacity in each country.

But bank finance also has its limits as it is not conducive to risk-taking (Demertzis et al 2021). To deal with these risks, the EU must develop deeper and more unified capital markets to finance riskier projects.

In the meantime, the lack of such risk finance means that the public sector must absorb some of the risk associated with delivering on longer-term and less-certain investments. Some of these investments may be strategic in nature. As not all countries have the same fiscal capacity, they may opt to pursue some of these European strategic objectives at different speeds.

This can be problematic. Pursuing, say, climate goals at different speeds may compromise the ability of all countries to achieve important milestones. This is why we see an important role for the EU to ensure that all countries advance at a minimum acceptable speed, at least for some of the most important European public goods, such as climate or connectivity.

With European elections in 2024, this is a natural point for the EU to reflect on its long-term strategy, including on how to invest beyond 2026, the year when the new European budget will have to be agreed and the NextGenerationEU initiative (NGEU) comes to an end.

We define the notion of strategic investment in the context of the EU, set out conditions for such investment to be co-financed by the EU and make recommendations about what these should be in the EU beyond 2026. We present first the EU’s main long-term objectives, in the context of the challenges it faces. All member states and the EU as an entity will have to plan how to accelerate investment to meet these objectives.

We discuss the rationale for EU-level financing of some of these objectives, alongside private sector and member state financing. EU involvement would necessarily require there to be value added, for example in the form of crossborder efficiency gains, in pursuing some of these long-term objectives.

This is necessary on economic grounds and is also crucial for democratic legitimacy and acceptability. Having identified projects that offer such efficiency gains, the EU needs to prioritise those that are strategic – in other words, pivotal to the EU’s economic interests and economic security.

We look at the EU’s previous efforts to finance long-term projects using funds from the European budget (Multiannual Financial Framework, MFF) and the newly established NGEU. We observe a lack of continuity in the instruments used to pursue these objectives as programmes span at most seven years and typically between three and five.

Also, multiple institutions oversee different programmes that sometimes have over-lapping objectives. Additionally, we look at how countries have used public investments to advance their own objectives, as a way of identifying best practices in terms of maximising the impact of public resources.

We make two main contributions in this study. First, we define strategic investment in the context of the EU and set out conditions identifying when to finance projects with EU resources. Strategic investment, in the form of gross fixed capital formation, is investment consistent with the EU’s long-term objectives and priorities.

We discuss when there is a good case for the EU to finance some of these strategic objectives directly, beyond what EU countries and the private sector do. When EU ‘additionality’ is established, it means that projects will be underprovided if left to countries or the private sector alone. Crossborder efficiency gains would be one example of a justification for EU financing.

Second, we formulate recommendations on how to think about European strategic investments, grouped into three categories:

1. Reform current funds and tools. The EU’s previous attempts to finance projects of strategic relevance have been characterised by a series of time-limited programmes. Such funds are finite in that they last only a few years, they come from different sources of funding, and they often overlap. We propose creating a dedicated fund for European Strategic Investments (ESIs).

The priorities in terms of achieving long-term objectives need to be evaluated periodically. Such continuity will require dedicated funds that can come in the first instance from a partly repurposed European budget (the MFF).

2. Put the European Investment Bank in charge. A dedicated fund will also require a dedicated manager. We argue that the EIB is the natural manager for such a fund. Financial support should be distributed on a project-by-project basis once the European added value has been established.

The EIB has the resources and skills to evaluate complex and technical projects and can build tools for transparent monitoring of projects.

3. Work towards new funding tools. The EU still needs to make progress with finding new ‘own resources’ to finance the debt it has issued under NGEU. At a later stage, a consequence of establishing new sources of income for the EU budget will be that the EU will have dedicated financing streams for ESIs as a way of ensuring continuity.

As ESIs are relevant to all EU citizens of current and future generations, they are a prime candidate to be financed by common EU resources and through long-term debt.

2 The EU’s long-term objectives and the role of public investment

In this section, we identify the long-term objectives the EU has set for itself. Then we summarise some of the budgetary needs that have been identified in the literature and discuss the benefits of public investment, as described by the literature.

2.1 The EU’s long-term objectives

As is the case for any investment, strategic investment needs to be consistent with a set of long-term objectives. This is necessary to ensure consistency in the way investments are selected and implemented.

European strategic investments should therefore be consistent with the long-term objectives set at EU level. Based on European Commission publications, we group high-level EU objectives into the following five groups.

1. Open strategic autonomy and competitiveness

The European Commission Joint Research Centre’s 2023 strategic foresight report (Matti et al 2023, p. 30) states that “Open strategic autonomy refers to the EU’s objective of strengthening independence in critical areas, supporting the EU’s capacity to act, while being open to global trade and cooperation.”

Open strategic autonomy became an important topic initially after the first supply chain interruptions during the pandemic, and later with the increased geopolitical tensions globally following the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

The objective of competitiveness refers to strengthening Europe’s global competitiveness. The EU needs to identify the conditions that will allow its industries to promote sustainable growth internally and to compete in global markets.

It is particularly important to ensure that new legislative proposals and high-level projects, such as the Twin Transition (see below), do not harm the region’s competitiveness. Fostering EU leadership in technology and cybersecurity have also been highlighted as crucial to ensure European competitiveness on the global stage.

2. Twin transition

EU policymakers employ the concept of the ‘twin transition’ when talking about transforming EU economies into more environmentally sustainable and more digitalised systems. The objectives of the landmark European Green Deal were set out in the European Commission’s priorities for 2019-20241.

They are: (i) no net emissions of greenhouse gases by 2050, (ii) economic growth decoupled from resource use, and (iii) not leaving any citizens behind in the transformation.

The digital transition aims to prepare businesses and citizens for the increasing importance of digital technologies. Building the necessary infrastructure to take advantage of new technologies is part of the ‘European Digital Decade’, as is enabling citizens to participate in transforming labour markets through re-skilling. Ensuring proper and safe development and use of artificial intelligence is also part of this objective.

3. Resilience and economic and territorial cohesion

The 2020 Strategic Foresight Report (European Commission, 2020a, p. 3) defined resilience as “the ability not only to withstand and cope with challenges but also to undergo transitions in a sustainable, fair, and democratic manner.”

This objective aims to prepare Europe for future economic, social and health shocks. Recently the concept has been captured by the notion of de-risking, which refers to the reduction of extreme dependencies on critical goods and promotes EU economic security. Fostering the resilience and strength of health systems in the EU is also part of this objective.

Economic and territorial cohesion refers to strengthening the internal cohesion of the EU, including efforts to address imbalances between countries and regions. The goal is to achieve a level playing field inside the EU for all economic players and to preserve the integrity of the single market. In the process, it is important to provide equal opportunities to all citizens across all regions.

4. Security and European values

The European Council listed “protecting citizens and freedoms” as part of its 2019-2024 agenda (European Council, 2019). The relevance of this theme has only increased with the Russian invasion of Ukraine. This objective includes securing the EU borders and ensuring the security of supply chains. Defending and promoting European values, such as ensuring and strengthening democracy and protecting the rule of law, is a key EU objective.

5. Open markets and rules-based multilateralism

Europe’s relationship with the rest of the world is defined by adherence to rules-based multilateralism and open markets. Supporting and cooperating with other regions and economies to achieve common goals, such as the twin transitions, is also part of this objective.

The Global Gateway facility – with an objective of investing internationally in high-quality and sustainable infrastructure to foster development and growth in partner countries – is an example of such a policy2.

The EU can play an important role in making sure that the necessary investments in energy and transport systems are done by all countries, while also safeguarding a fair transition

2.2 European budgetary needs

The European Commission has identified a series of budgetary needs to be met for the EU to meet its long-term objectives. These span several areas. A non-exhaustive list includes:

1. Climate and energy transition. Pisani-Ferry et al (2023) reported that for the EU to achieve a 55 percent emissions reduction by 2030, compared to 1990, it will need annual additional investment (compared to investment levels from 2011 to 2020) amounting to about 2 percent of GDP (€356.4 billion).

This represents investment in energy and transport systems. Pisani-Ferry et al (2023) also estimated that when it comes to the green transition, annual public investment is expected to be within 0.5 percent to 1 percent of GDP in the future (see also Darvas and Wolff, 2022). A substantial part of the gap will need to be filled by the private sector.

Lenaerts et al (2021) reported similar numbers that go beyond 2030 and studied how to reach climate neutrality by 2050. More specifically, achieving the benchmarks set forth in the ‘Fit for 55’ package – a body of EU laws facilitating the reduction of net EU greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55 percent by 2030 compared to 1990 – would demand annual investment of approximately €487 billion for the energy sector and €754 billion for the transportation sector from 2021 to 2030.

Additionally, REPowerEU, a programme put together after the Russian invasion of Ukraine to increase the EU’s energy resilience by decoupling from Russian fossil fuels, entails total investment of €210 billion between now and 2027 (European Commission, 2022a).

2. The digital transition. Bridging the investment gap within the EU for the digital transition will entail a minimum annual expenditure of €125 billion between 2020 and 2030 (European Commission, 2020b). According to Papazoglou et al (2023), the principal EU funding instruments – the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF), the Connecting Europe Facility 2 (CEF2) Digital, the Digital Europe Programme, Cohesion Policy and Horizon Europe – will contribute a total of over €165 billion up to 2027 to support the Digital Decade targets, to be achieved by 20303.

More than 70 percent of these funds will come from the RRF. Ockenfels et al (2023) estimated an overall investment gap of at least €174 billion to meet just two of the twelve Digital Decade targets (specifically the fixed Gigabit coverage and providing ‘full 5G service’). Again, they argue that the private sector will have to play a major role to fill this gap.

3. Defence and security. The financial implications of the new geopolitical landscape are also substantial. Defence spending by EU countries reached €214 billion and €240 billion, in 2021 and 2022 respectively (European Defence Agency, 2023). This marks the eighth year of consecutive growth in defence spending. Several EU countries still fall short of their NATO obligation of military spending of 2 percent of GDP.

4. Reconstruction of Ukraine. The reconstruction efforts in Ukraine will necessitate a collective contribution of €384 billion from all partners over the next decade (World Bank, 2023). This amount will increase in line with the duration of the war, and it is also expected that the private sector will bear a part of that.

In 2021, the Council of the EU approved the establishment of the European Peace Facility (EPF), with a current financial ceiling exceeding €12 billion. The EPF aims to prevent conflicts, promote peace and enhance international security.

In October 2022, the EU Military Assistance Mission in support of Ukraine (EUMAM)was formed with the purpose of providing individual, collective and specialised training to Ukraine’s Armed Forces, and to coordinate and synchronise the activities of member states delivering this training.

5. Health Union. Similarly, an EU4Health programme with a budget of €5.3 billion was put together in 2021 for the period 2021-2027 to advance the EU’s health policies, towards a European Health Union, intended to ensure collective preparation for, and response to, health crises4.

Amounts stated above include both investment and spending needs, as it is often not possible to separate the two. From 2021 to 2027, EU spending power is just over €1800 billion, of which €1050 comes from the MFF and €750 billion from NGEU. This amounts to an average of €257 billion in annual spending power.

This average annual total spending power falls significantly short of the €356.4 billion in additional annual investment needed for the green transition alone, as estimated by Pisany-Ferry et al (2023). Even if the EU were to spend its entire budgetary resources only on the green transition, it would fall very short of what is needed.

And that is only one of the EU’s objectives. This is why many voices have called for private investment to be mobilised to help achieve the EU’s objectives.

EU policymakers recognise the importance of maximising crowding-in of private capital for strategic projects. This was a central aim of two EU investment programmes: the investment plan for Europe (the so-called ‘Juncker Plan’) and InvestEU (see section 4.2 for details of these programmes).

These two initiatives were established in 2015 and 2021, respectively, to increase overall investment levels in the EU. EU initiatives need to be careful to maximise the impact of the limited resources, including by avoiding the crowding-out of private-sector investment. Instead, private investment should be facilitated by EU actions.

These include participating in the financing of projects, by picking up the risk tranches that the private sector is reluctant to take on, reducing red tape and unifying regulatory frameworks for infrastructure. The scarcity of resources also underlines the importance of well-designed allocation mechanisms and the prioritisation of objectives.

EU countries have a crucial role to play by deploying public funds to help finance investments of strategic relevance for the EU. But not all countries have the same ability to play a role in this regard. Darvas et al (2023a) reported that the European Commission projects that 18 of 27 EU countries will have either a debt level above 60 percent of GDP or a budget deficit above 3 percent of GDP in 2024, which under the old fiscal framework5 would trigger the EU excessive deficit procedure (EDP).

The EDP was suspended in 2020 because of the COVID-19 pandemic but its reinstatement is planned in 2024. A reform of the EU fiscal framework agreed at the end of 2023 requires from EU countries very ambitious fiscal adjustment of more than 2 percent of GDP over the medium term, in addition to what had already been planned for 2023-24 (Darvas et al 2023b).

In addition, there is also the issue of the speed at which countries are asked to reduce debt, which will constrain some countries even further in the medium term (after countries have brought their deficit below the level of 3 percent of GDP.

Budgetary limitations and the need to reduce high levels of debt will directly affect the ability of countries to undertake strategic investments at national level. Part of the rationale for pursuing certain ESIs at EU level is based on the need for all member states to advance at a common minimum speed to ensure that EU long-term objectives are not threatened by lack of progress in individual countries.

Tighter fiscal rules might lead countries to cut back on investment support, increasing the importance of a well-defined framework for EU strategic investments.

Given the importance of the issue of how to finance the EU’s objectives, the discussion goes beyond the two main current tools, the MFF and NGEU, and touches on the wider issue of EU fiscal capacity.

One possibility is to pool resources at EU level, in other words to establish a stream of additional ‘own resources’ that can be used to fund, among other things, strategic investments. For the moment the discussion on own resources is motivated by the need to repay NGEU borrowing, which involved the largest EU bond issuance in its history.

As a one-off instrument however, own resources are also finite. We argue that if permanent new income streams were to be established, then ESIs would be the next natural candidate item to be funded through vehicles other than the MFF.

European Commission (2021) proposed three new sources of revenue for the EU budget: 1) the EU emissions trading system, 2) the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), and 3) taking an allocation from member state taxes on the largest multinational companies.

The European Parliament supports these three sources of revenue and has asked the Commission to also explore several other potential sources as a basis for own resources, including corporate taxation (derived from a aggregation of the corporate tax base in the EU, as put forwards in the Business in Europe: Framework for Income Taxation (or BEFIT proposal), a tax on cryptocurrencies, a tax related to the digital economy, a financial transactions tax (FTT) and an EU ‘fair border tax’ (European Parliament, 2023a).

In a February 2023 resolution, the European Parliament (2023b) urged the Commission and member states to make progress on adopting an FTT to help the EU boost its industrial competitiveness and other policy priorities.

To that we would add the point that temporary issuance of debt for the RRF meant that the EU did not benefit from its full potential (Claeys et al 2021). Even though the European Commission followed the diversification practices of big issuers, the markets still priced a premium on this debt over and above what fundamentals justify.

This was a consequence of: i) the issued volume being small and therefore not fulfilling the purpose of issuing a significant new safe asset, and ii) the issuance being presented as a one-off event, thus making it less attractive to investors. A permanent stream of own resources would lead to more favourable issued debt by the EU than now.

Last, the intergenerational nature of ESIs makes a case for financing them with intertemporal means, such as long-term debt issued by the EU. Naturally, other instruments than debt issuance should also be considered (Helm, 2023).

2.3 The macroeconomic impact of public investment

The role of public investment in promoting economic growth has been studied extensively in the literature. The consensus is that public investments have a positive multiplier effect on the economy, but the magnitude of this multiplier effect varies depending on the economic situation, the composition of investments and the economy’s absorption capacity.

Public investment is seen as a potential driver of long-term growth by catalysing private sector investment and by enhancing productivity by modernising infrastructure, stimulating innovation and promoting education.

Moreover, public investment can play a crucial role in stabilising the economy by mitigating the negative effects of economic contractions. The EU Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) offers a good example, having the objective of supporting investments in the twin transition during a severe recession when public resources were very limited.

By helping to sustain the course on meeting long-term targets, the RRF has relieved national budgets and allowed countries to deal with the serious contraction during the pandemic.

Based on the literature, we summarise next the effects of public investment on the macroeconomy.

2.3.1 Impact on economic growth

Public investment in infrastructure and education has played a central role in growth and poverty reduction strategies designed by many developing countries in recent decades (United Nations, 2020). This role is only likely to increase in importance in a post-COVID-19 world as countries seek to restore pre-pandemic growth rates and repair the scarring effects that lockdowns and closures have inflicted on human capital (Agarwal, 2022; Larch et al 2022).

There is a substantial body of work that seeks to quantify the macroeconomic effects of such investment efforts and its financing (Atolia et al 2021; Gurara et al 2019; Zanna et al 2019).

An increase in public investment can affect economic growth in two ways. First, an increase in public investment has positive effects on aggregate demand. Second, efficient public investment can contribute to the economy’s productive capacity by increasing the stock of public capital.

However, it is important to consider the costs and benefits of additional public capital carefully, taking into account the financing alternatives and their effects on output and public finances. Considerable uncertainty surrounds the size of short-term fiscal multipliers.

They are, for example, larger during recessions, but found to be smaller in the presence of weak public finances, particularly when debt sustainability is at risk. In addition, multipliers depend on how the expenditure is financed, through debt, increases in revenues or cuts to other expenditure categories.

Empirical estimates of the effect of public capital on output tend to be positive but variable (Romp and De Haan, 2007). Studies by Barro (1988) and Aschauer (1989b) found that increases in public capital, such as infrastructure investment, have a positive impact on long-term economic growth by contributing to the economy’s productive capacity.

Meta-analyses reveal an average long-term elasticity ranging from 0.12 (Bom and Ligthart, 2014) to 0.16 (Nuñez-Serrano and Velazquez, 2017) for public capital. Thus, for every 1 percent increase in public capital, long-term output tends to increase by somewhere between 0.12 percent to 0.16 percent, which is far below Aschauer’s (1989b) estimate of 0.39 percent.

Abiad et al (2016) found positive and significant effects of public investment on output for advanced economies, both in the short-term and long term. For low-income developing countries, Furceri and Li (2017) found a positive effect of public investment on output in the short and medium terms. Ramey (2021) underlined the macroeconomic perspective on government investment, offering robust evidence in favour of the enduring advantages of infrastructure expenditure.

2.3.2 Impact on productivity, job creation and inequality

One of the primary channels through which public investment affects economic growth is by enhancing productivity. Infrastructure investment, such as roads, bridges and telecommunications networks, reduce transportation costs and improve the overall efficiency of the economy (Munnell, 1990).

Public investment also plays a vital role in job creation. Investment in infrastructure projects generates employment opportunities in construction, engineering and related industries. Cingano et al (2022) evaluated a public investment subsidy programme in Italy. Under this scheme, funds were allocated through calls targeting different sectors, primarily in industry. The main objective of this policy was job creation.

The authors found that the policy induced the desired behavioural response in terms of job creation: firms benefitting from the programme increased investment by 39 percent and employment by 17 percent over a six-year period, compared to similar firms not eligible for the subsidy.

Infrastructure investment can have an impact on income inequality beyond its effect on aggregate income. Infrastructure can improve the access of the poor to services and productive opportunities. It can also improve access to human capital.

Infrastructure can also support the integration of poor and marginalised communities into the wider society and economy (Calderón and Servén, 2014). Empirical evidence indicates that infrastructure development and access is negatively correlated with various measures of inequality, although with some measurement limitations (for an overview see Calderón and Servén, 2014). While the evidence on infrastructure and inequality is limited, the impact on inequality should be taken into account when planning infrastructure projects.

2.3.3 Differences between countries and investment types

The effectiveness of public investment is shown to depend on a country’s level of development, institutional quality and governance. Governance of the public investment process affects the macroeconomic effects of public investment in different ways (Miyamoto et al 2020).

Countries with stronger governance achieve a stronger output impact of public investment. Stronger infrastructure governance6 helps public investment yield a higher growth dividend by improving investment efficiency and productivity, and it stimulates private-sector investment.

By contrast, weak infrastructure governance is shown to crowd out private investment, lead to higher debt-to-GDP ratios and cause significant waste of public money, all of which have a negative impact on output, even after sizeable public investments.

Moreover, the type of investment matters. While infrastructure, education and healthcare investments are all recognised as having positive effects on output, the effect varies in magnitude (Ramey, 2021; Atolia et al 2021).

Holmgren and Merkel (2017) performed a meta-analysis of the relationship between infrastructure investment and economic growth. They found significant variance in the effect of infrastructure investment on production.

Specifically, the estimated effects of a one percent increase in infrastructure investment range from a 0.06 percent decrease to a 0.52 percent increase in output. The effects appear to vary depending on the type of infrastructure in which the investment is made, and the type of industry.

A more recent line of research indicates that investment multipliers are more pronounced for green investments. According to Batini et al (2022), spending on clean energy, such as solar, wind or nuclear, exerts a GDP impact approximately two to seven times greater (depending on the technology and timeframe analysed) than spending on non-environmentally friendly energy sources, including oil, gas and coal.

Afonso and Rodrigues (2023) studied the impact of public investment in construction and R&D in 40 countries, notably on economic growth and on crowding-out effects on private investment. They compared the effects of these investments in emerging and advanced economies by controlling for the level of economic development.

They found that: i) innovations in public investment have more positive effects on GDP growth and private investment in emerging economies; ii) the positive impulse of public investment on the private sector is pronounced and significant in emerging economies; iii) government construction investment has a more positive effect on economic growth in emerging economies; iv) innovations in public construction crowd out private investment spending in advanced countries; v) emerging economies benefit from public R&D investment.

Two recent, timely papers (Kantor and Whalley, 2023; Gross and Sampat, 2023) showed that public R&D may have large effects locally and also at the aggregate level. Both papers examined episodes of applied public R&D ‘moonshots’: the US government’s massive R&D effort during the Second World War and the US Apollo mission in the 1960s that culminated in the moon landing. In both cases the level of public investment was massive.

Bloom et al (2019) discussed several of the main innovation policy levers and described the available evidence on their effectiveness: tax policies to favour research and development, government research grants, policies aimed at increasing the supply of human capital focused on innovation, intellectual property policies and pro-competitive policies.

They brought together this evidence into a single-page ‘toolkit’, in which they ranked policies in terms of the quality and implications of the available evidence and the policies’ overall impact from a social cost-benefit perspective. The authors found that, in the short term, R&D tax credits and direct public funding prove most impactful.

However, increasing the supply of human capital yields greater effectiveness in the long run. Additionally, while competition and open trade policies may offer somewhat modest benefits for innovation, they are cost-effective.

In conclusion, there is general agreement that public investment can play a positive role in economic growth and the achievement of policy objectives. However, the effective implementation of these investments and their alignment with economic and policy priorities are pivotal to their success.

3 Defining European strategic investments

The term ‘strategic investment’ is used often but very seldom defined. In his award-winning book Chip War, Chris Miller (2022) quoted a Reagan Administration economist who, in response to the multiple Silicon Valley requests for support for the semiconductor industry, invoking its strategic relevance, stated: “Potato chips, computer chips, what’s the difference? … They are all chips. A hundred dollars of one or a hundred dollars of the other is still a hundred.”

The quote illustrates the lack of a common definition of the notion of ‘strategic’. Is strategic something that you cannot do without, or is it something that aims to achieve long-term objectives, or possibly both, or something else entirely?

According to the Cambridge Dictionary, the term strategic refers to investments made by a company with the intention of enhancing its long-term success. This might involve investing in a new business that offers access to new markets or developing innovative products.

Milgrom and Roberts (1992) defined strategic investments as investments that benefit the entire organisation, not just the specific unit making the investment decision. These investments are crucial for businesses as they can lead to competitive advantages through cost reduction and product differentiation, ultimately creating value (Porter, 1980; Makadok, 2003). These definitions from the business context have only limited application to a policy context.

A common theme in these definitions is the emphasis on long-term impact. Strategic investments are typically seen as financial commitments made with a focus on creating long-term value, rather than seeking short-term returns. In essence, they involve allocating financial resources to projects, assets or initiatives aimed at achieving specific long-term objectives and strengthening an organisation’s competitive edge.

Closer to the policy context is the concept of strategic investment funds. Divakaran et al (2022) defined such funds as having six attributes: i) they are initiated and (partially) capitalised by governments or quasi-sovereign institutions, ii) they invest primarily in unlisted assets and aim to achieve financial returns as well as pursue policy objectives, iii) they aim to mobilise co-investment from private investors, iv) they provide long-term, patient capital (mostly, but not exclusively, equity), v) they operate as professional fund managers seeking financial returns for their investors, and vi) they are investment funds established as separate legal structures.

Looking at the EU’s past efforts labelled as strategic investments, this definition is only a partial fit. In particular, achieving financial returns has not been a major objective of some of the main strategic investment initiatives in the EU.

3.1 European strategic investments: a working definition

Bringing together insights from the literature, and international and EU experiences with strategic investment, we define ‘European strategic investments’ (ESIs) as follows:

Investments, defined as gross fixed capital formation, carried out at the national or EU level are ESIs if they are consistent with the EU’s long-term objectives and priorities7.

The term ‘strategic’ must provide a rationale for prioritising investments and therefore the order in which long-term objectives are pursued. European strategic investments can be financed by the private sector, by EU countries or with EU financing. Therefore we supplement our definition with:

The decision to (co-)finance some of these ESIs at the EU level additionally requires that those investments are European public goods (EPGs). This means that there is added value to be had by pursuing investment at the EU level instead of solely at member state level.

Not all European public goods are investments as some might refer to consumption, for example, common procurement of vaccines. Equally, not all investments that are EPGs are necessarily strategic, in other words, of the highest priority.

In this paper, we only focus on ESIs that merit EU financing according to the thinking just described. However, the objective is to encourage the participation of both the private sector and member state governments. The remainder of this section discusses the concepts of EPGs and ‘strategic’ in more detail.

3.1.1 What are European public goods (EPGs)?

A starting point for the provision of any public good is the presence of a market failure that prevents the private sector from taking up a specific economic activity. In the presence of externalities, a good or service either will not be provided or will be underprovided by the markets.

For EPGs, there is also a failure at the national level, in that a good or service will not be provided or will be underprovided if EU countries are left to provide for it individually.

The concept of EPGs encompasses the concept of additionality that is cited in the regulations that underpin many EU investment instruments. Additionality means that EU financing does not displace financing from any other source.

In other words, the additionality principle states that the project would not be realised, or not to the same extent, without EU financial support. Importantly, efficiency gains such as shorter delivery times or lower cost can also satisfy the additionality principle.

Fuest and Pisani-Ferry (2019) justified the provision of a public good at the EU level when the benefits of doing that exceed the benefits of providing it at member state level. Such added value could come from economies of scale, crossborder spillovers and similarity in country preferences and interests.

Efficiency gains at the EU level would come either through crossborder spillovers or through cost-savings arising from economies of scale if a good is financed at the EU level rather than separately by each country. Buti et al (2023) argued that providing EPGs could strengthen cohesion across countries and, therefore, also benefit the EU as a political entity.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic crisis and then the energy crisis following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the discussion on market failures has broadened to include not only the under-provision of a good or a service, but also the issue of underinvestment in resilience (Grossman et al 2023).

The idea here is that firms themselves might be individually sufficiently diversified in how they organise their supply chains, for example, but sectors might not. This could make a sector vulnerable and could, if economically systemic, pose a significant risk to a whole country’s ‘business continuity’.

Public intervention is then justified as a way of internalising this systemic vulnerability. The rationale suggests that if efficiency gains are achievable at the EU level, say because of crossborder spillovers, conducting this public intervention at the EU level is most fitting.

An example of such a vulnerability that unravelled was relying entirely on imports for the provision of face masks at the start of the pandemic, a good that was critical for safeguarding public health.

The question then is, what public goods can achieve efficiency gains if provided at the EU level? Buti et al (2023) identified six areas where EPGs exist: digital transition, green transition and energy, social transition, raw materials, security and defence, and public health.

These public goods could include both investment (for example in infrastructure) and consumption (as the joint purchase of face masks), or could require joint action at EU level (for example procurement). In our definition of European strategic investments that are eligible for EU financing, we thus only include EPGs that refer to investments.

3.1.2 When is an investment strategic?

A common theme that underpins all definitions of strategic investment is the need to respond to long-term objectives. However, long-term investment has been challenged in the past 15 years with the world economy hit by extreme shocks that originated in very different geographies and parts of the economy.

Extreme events now occur seemingly more often, and it is no longer safe to assume that similarly severe shocks will not continue to occur. A financial crisis, followed by a pandemic and more recently the Russian invasion of Ukraine that has forced the EU to reconfigure its energy relationships, all in the space of 15 years, has meant that investments have had to be delayed or re-prioritised to deal with urgent issues.

In response to these three extreme shocks, the EU has had to redefine its priorities. The financial crises required the EU to invest in strengthening its institutional power to monitor and safeguard its banking sector.

The pandemic required protecting the economic value of households and firms, prioritising the financing of critical goods such as vaccines and reassessing the length of international supply chains. The energy crisis has forced the EU to change its energy mix and rethink how it can secure its energy supply.

Arguably, some of the investments made in fossil fuels in the EU to ensure energy security (such as in liquid national gas terminals or the re-opening of coal mines) can be understood as an example of reprioritising the objective of energy security above climate objectives, at least in the short run. No one could doubt that such investments were of strategic relevance to the EU’s interests.

Nevertheless, adhering to long-term objectives remains crucial in the process of identifying strategic investments. The challenge for policymakers in identifying and pursuing ESIs is to navigate the high levels of uncertainty present while remaining consistent with a long-term vision.

3.2 Examples of European strategic investments

A non-exhaustive list of projects that are ESIs potentially qualifying for EU financial support under our definition would include8:

Energy infrastructure and projects boosting energy efficiency, especially crossborder projects. These include power plants, power grids and energy-storage facilities. There is a strong case for EU action since reaching the EU’s climate goals depends strongly on the European energy mix and the infrastructure to transfer energy across the Union. The actions of a single country will benefit or harm the global climate, and therefore have direct implications for other EU countries.

Projects with a direct crossborder element, such as crossborder grids or grid interconnectors, could particularly benefit from EU action. While not necessarily constituting infrastructure, projects to boost energy efficiency, such as the refurbishment of buildings, would also qualify as being of EU value added.

ICT infrastructure, especially crossborder projects. This category includes infrastructure needed to connect European citizens within and across borders. Examples would be the 5G rollout or the development of optical fibre networks. Fast internet connections are becoming increasingly important for European competitiveness. Ensuring the continuity of services across borders would benefit the EU as a whole and justify EU action.

Transport infrastructure, especially crossborder projects. This category includes projects that physically connect European citizens and goods, as well as connections with the rest of the world, for example, roads, railways and ports. EU support is justified particularly for crossborder projects or facilities on important European transport axes. Projects that aim to make transport more sustainable, such as electric-vehicle infrastructure or sustainable urban transport infrastructure, should also be considered.

Facilities enhancing economic security and resilience. Within this category are essential facilities that, if absent, would pose a threat to the EU’s economic security and autonomy. An example of such critical industries would be critical raw materials or semiconductors.

When it comes to economic security, the EU needs to consider strategic investments as part of the broader aim of diversifying its sources of supply. The objective is not to eliminate dependencies but to safeguard business continuity through a mix of international trade and domestic production.

Facilities and projects boosting innovation. Research and development infrastructure and projects with an expected significant impact on innovation in the EU would also qualify for EU financial support under the ESI programme. Innovation will be crucial to the EU’s global competitiveness and economic growth.

This category includes physical facilities and programmes supporting the EU’s objective to be a global leader in innovation, such as research hubs and R&D projects in strategic sectors. This group could also include social infrastructure projects important for citizens’ welfare, such as research hospitals and medical research facilities.

4 EU programmes to finance long-term objectives

This section focuses on the EU’s approach to long-term investment. We develop a taxonomy of the EU’s public investment instruments and initiatives and examine the outcomes in terms of private capital mobilisation.

4.1 Taxonomy of EU public investment instruments and initiatives

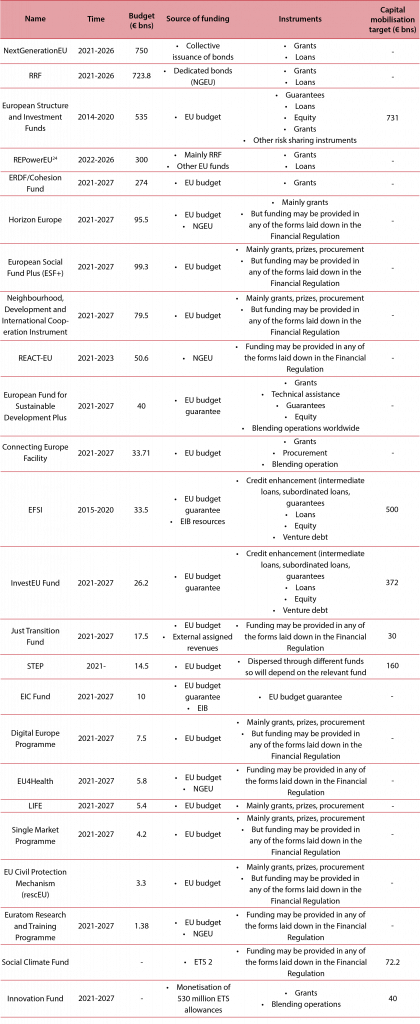

We have identified 24 public investment initiatives implemented by the EU that are relevant to our study.

We discuss the six largest and most important initiatives in more detail: the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF), REPowerEU, the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) and the Cohesion Fund (summarised in a single item because they share the same EU regulation), Horizon Europe, the European Fund for Strategic Investments (EFSI), and InvestEU.

We focus on these programmes because of their size and relevance to the concept of strategic investment in the EU.

We describe here briefly the purpose of each of these programmes and include a detailed taxonomy of all EU initiatives in Appendices 2 and 39.

1. The RRF, created in 2020, provides €723.8 billion in grants and loans to support reforms and investments in EU countries. It is the centrepiece of NGEU, a temporary recovery instrument to support the economic recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic and to build a greener, more digital and more resilient future for the EU. NGEU is worth €806.9 billion as of 2023 and is scheduled to operate from 2020 to 202610.

2. The related REPowerEU initiative was put together to help deal with the energy crisis following the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022. It aims to facilitate an affordable phase-out of Russian gas by 2027 and was funded by the €225 billion at the time still available in the loan component of the RRF that had not been claimed by member states.

To support REPowerEU, the financial envelope was increased with €20 billion in new grants. These grants will be financed through the frontloaded sale of emissions trading system (ETS) allowances and the resources of the Innovation Fund11, to be partly replenished through the Market Stability Reserve12.

Additionally, EU countries have the option to voluntarily transfer €5.4 billion of funds from the Brexit Adjustment Reserve13 to the RRF to finance REPowerEU measures. This comes on top of the existing transfer possibilities of 5 percent from the cohesion policy funds14 (up to €17.9 billion).

3. The ERDF and Cohesion Fund, with a total budget of €274 billion between 2021-2027, are dedicated to reinforcing economic, social and territorial cohesion within the EU.

4. Horizon Europe, with a total budget of €95.5 billion, is the EU’s primary funding programme for research and innovation. It will be implemented in the period between 2021-2027.

5. The EFSI is the main vehicle of the investment plan for Europe (also known as the ‘Juncker Plan’), created in 2015 to boost competitiveness and growth by helping unlock European Investment Bank financing for economically viable projects that would normally have been considered too risky for EIB participation. It pledged €33.5 billion and aimed to raise €500 billion by 2020 (a goal that was achieved; see section 4.2).

6. Finally, InvestEU the successor to the Juncker Plan, was created in 2021. Just like its predecessor it aims to enhance EU competitiveness, innovation, sustainability and social cohesion. It has pledged €26.2 billion and aims to raise €372 billion in investments.

The EU regulations underlying each of these instruments define the projects eligible for investment in terms of objectives rather than sectors. These objectives are typically very broad and therefore often overlap between programmes.

Projects enhancing the competitiveness, socio-economic convergence and cohesion of the Union, particularly in the realms of innovation and digitisation, are covered by all six instruments. The same is true for projects fostering sustainability, inclusiveness in the Union’s economic growth and social resilience, including education, social infrastructure and training programmes.

All initiatives also aim at increasing access to finance for small and medium and mid-cap companies. Finally, meeting the sustainability and climate EU objectives figure prominently in each initiative.

Importantly, the regulations underlying all these recent initiatives, with a specific exemption concerning immediate energy security aims in REPowerEU and Horizon Europe, include a ‘do no significant harm’ clause, meaning that projects financed under these programmes cannot go against EU environmental objectives.

Programmes are managed and governed by different entities, but any given project can qualify for several of these programmes. Programmes are also targeted at different entities. For example, InvestEU funding is targeted at projects, while funding from the Cohesion Fund is disbursed to regions. Streamlining the number of initiatives could yield efficiency gains for strategic investment at the EU level.

Table 1. Shortened taxonomy of the main investment initiatives at EU level

Note: RepowerEU funds are for the most part from the unclaimed funds in the RRF and are therefore not new money.

Source: Bruegel.

Two main takeaways emerge from Table 1. The first is that there are two sources of funding for these programmes: the EU budget (MFF, either through direct funding or providing a guarantee) or funds raised through borrowing in the context of NGEU. Long-standing investment programmes that have been present in the EU budget for several political cycles, such as Horizon or predecessors of the ERDF or Cohesion Fund, are mainly funded with resources from the EU budget.

The RRF (and REPowerEU) are funded through an issuance of EU debt in capital markets. NGEU, created during the pandemic, was remarkable for two reasons: first, it increased EU spending capacity by 75 percent; second, it was financed by the issuance of debt. The EU had issued small levels of debt in the past to finance loans.

It was the first time, however, that it issued such high levels of debt and that it issued debt to fund grants to member states. It is worth noting that a big part of the loan component of the RRF was not taken up by many countries at the start of the RRF, even if for some countries the interest rate charged under the RRF was lower than the market rate.

Subsequently, the existence of this underutilised pot allowed the money to be repurposed to deal with energy security under REPowerEU. EFSI and the InvestEU Fund are funded through a more recent financial structure — a guarantee from the EU budget.

The idea of a guarantee backed by the EU budget was born against the background of limited EU resources to spur investment when EFSI was designed (Claeys, 2015). Using the guarantee to absorb potential losses could attract private investors to projects that are considered too risky without the guarantee.

EFSI is one of the few programmes for which ex-post evaluation is possible since it started in 2015. Its target of mobilising over €500 billion based on €33.5 billion of resources would result in a target multiplier of over 1515. According to EIB analysis, this target was achieved (Wilkinson et al 2022). Therefore, the guarantee seems to have fulfilled its purpose.

However, as noted by Claeys (2015), the programme would only have been truly successful if it unlocked financing for projects that would not have been financed otherwise. Claeys and Leandro (2016) cast some doubt on this issue for the projects financed by EFSI in its first year. The EIB acknowledged that it cannot verify that all financed projects would not have been financed without its support (Wilkinson et al 2022).

Only EFSI and the InvestEU Fund set explicit targets for mobilising private investment. Additionally, the Horizon Europe regulation mentions maximising the mobilisation of private capital where possible. Finally, the RRF regulation mentions mobilisation of private capital, but rather as an additional benefit than an objective in itself.

When EFSI was announced, it was uncertain whether the EU budget guarantee would truly change the tendency of the EIB to invest in relatively low-risk assets (Claeys, 2015). According to the EIB, EFSI altered the riskiness of its portfolio with EFSI projects being on average riskier than other projects financed by the EIB.

However, as of 2022, the cumulative number of guarantee calls was modest, at approximately €184 million. This relatively low amount could suggest that a guarantee from the EU is enough to unlock financing for most projects executed under EFSI, without significantly increasing the burden on the EU budget.

On the other hand, the low default rate of projects could simply suggest that the projects were not very risky to begin with, and that the EU budget guarantee has not led the EIB to invest in significantly riskier projects.

In this regard, it should be noted that the EIB has a fiduciary duty towards the EU budget with regards to operations under the budget guarantee, and therefore a low default rate should be seen as positive.

The second takeaway from Table 1 is that programmes differ regarding the financial instruments used to finance projects of interest. The programmes funded by the EU budget or bond issuance (RRF, REPowerEU, Horizon Europe, ERDF and the Cohesion Fund) mainly use loans and grants.

The programmes funded by an EU guarantee and managed by the EIB use loans, equity, venture debt and credit-enhancement instruments. EFSI and InvestEU reflect a broader spectrum of capital market instruments. Credit-enhancement products in particular can be suitable for financing infrastructure projects (OECD, 2021).

These products transfer risk from investors to the EIB (backed by the EU budget) and can reduce the cost of financing while attracting additional investors16. Diversifying the range of financial instruments available to projects and companies is important for optimising resources and adapting the financing structure to project needs.

Some of the lessons learned from EFSI were embedded in the design of its successor, InvestEU. For example, under the EFSI regulation, the only implementing partner for financing projects was the EIB. A side-effect of this was that only relatively large projects were eligible for EFSI financing. Under InvestEU, the range of implementing partners was extended to local institutions.

The RRF required member states to prepare Recovery and Resilience Plans (RRPs) that detail national programmes of reforms and investments over the RRF period (up to 2026). Of the plan’s total allocation, 37 percent and 20 percent should be allocated to the climate and digital objectives, respectively.

RRPs have been assessed by the European Commission and endorsed by the Council. The assessments comprise development of two documents, a Council Implementing Decision (CID), and a staff working document (SWD). Milestones and targets are associated with each reform/investment (and detailed in the CID). The Commission disburses the funds after achievement of the pre-agreed milestones and targets at each payment request. Disbursement of funds is thus conditional on reaching milestones and targets.

The RRF experience will yield valuable lessons on the viability of making funding available to member states for strategic investments in combination with implementing structural reforms.

At the outset, however, while the grant component of the RRF was taken up by all countries, only a limited number of countries took up the loan component in the beginning17 (Demertzis, 2022). This meant there were funds available that could be redirected to REPowerEU. Taking into account the latest requests at time of writing, take-up of the total loan component of the RRF (€385.8 billion) now amounts to €292.6 (or 76 percent). Some of the latest loan requests are still subject to formal approval18.

Member state performance in the context of the RRF remains to be evaluated. The RRF is a performance-based programme, in the sense that the disbursement of funds is conditional on countries achieving milestones and targets. But Darvas et al (2023a) argued that Article (2) of the regulation defines ‘milestones and targets’ as “measures of progress towards the achievement of a reform or an investment.” The expression “measures of progress towards” thus indicates a process, not necessarily the achievement of results. This has also been observed by the European Court of Auditors (2023).

Therefore, a clearer definition of ‘performance-based’ is needed and should be based on outputs and results. There is also discussion on whether the milestones and targets set are sufficiently ambitious. As mentioned by Corti et al (2023), Italy will successfully fulfil its milestones and targets but will likely not achieve some of the objectives of the measures included in its RRP, including reducing regional and local inequalities in the provision of employment and childcare services. This could indicate that milestones and targets defined under RRF are too easy to achieve and not necessarily what the programme aims for.

Last, Claeys et al (2021) claimed that the temporary nature of NGEU borrowing, and its relatively small scale compared to borrowing by national governments, increased the cost of debt. Permanent EU borrowing would be more widely accepted by financial investors and could have the added benefit of creating a true European safe asset.

In addition to providing financing for projects, EU investment initiatives have also created auxiliary services to facilitate investments. For example, the European Investment Advisory Hub, established in 2015 alongside EFSI, aimed to enhance investment after the economic crisis. The Hub provides advisory services to project promoters to support investment in the real economy.

The Hub’s objective is described (in Regulation 2015/2017) as building on existing EIB and Commission advisory services in order “to provide advisory support for the identification, preparation and development of investment projects and act as a single technical advisory hub for project financing within the EU.”

However, a report from the European Court of Auditors (2020) highlighted concerns. The Hub was deemed a ‘demand-driven’ tool without sufficient prior assessment of its advisory needs, potential demand or required resources. While it satisfactorily offered tailored advisory services, it lacked a clear strategy for targeting support where it could maximise value. Some beneficiaries questioned the uniqueness of Hub support compared to other advisory sources.

Moreover, only over 1 percent of EFSI-supported financial operations benefited from Hub assignments. Additionally, the Hub lacked proper procedures to follow up on investments resulting from its assignments, hindering performance evaluation.

By the end of 2018, the Hub had completed too few assignments to contribute significantly to boosting investment. These findings were considered in the design of its successor, the InvestEU Advisory Hub.

This Hub has replaced thirteen19 centrally managed advisory programmes and is the central entry point for advisory and technical assistance requests. InvestEU Advisory Hub partners provide project advice, capacity building and market development support to promoters and intermediaries. The Advisory Hub is aligned with the objectives of the InvestEU programme.

4.2 Leveraging private capital

One of the goals of past ESI initiatives was leveraging private capital. The two largest initiatives, the EFSI and InvestEU, have aimed explicitly at maximising the mobilisation of private capital. EU policymakers acknowledge that the investment volume needed to achieve long-term political objectives will need to be largely supplied by the private sector (European Commission, 2023a). Therefore, future efforts for ESI should also focus on maximising private-sector participation in investment projects where possible.

From a macroeconomic perspective, several studies document the positive effect of public investment on attracting private investment (Aschauer, 1989a; Abiad et al 2016; Pereira, 2001; Brasili et al 2023). Abiad et al (2016) showed that the effect is greater in times of economic slack and when public investment efficiency is high.

Brasili et al (2023) showed a positive effect of local government investment on private investment, while evidence from Brueckner et al (2022) suggested that local governments are more efficient in crowding-in private investment than national governments. Focusing on public R&D support programmes, Azoulay et al (2019) and Moretti et al (2019) showed that public R&D spending crowds-in private R&D investment.

Turning to the experience of past and present EU strategic investment initiatives, such public efforts can mobilise private investment in four ways. First, a public sector entity can finance or secure the riskiest tranche of capital of an investment project that private investors are unwilling to take on, leaving them the less risky part.

Second, public investment, notably in SMEs and mid-caps, can result in increased corporate investment. Third, having a large public institution with a good track record as part of the investor mix can enhance the credibility of a project.

Fourth, public investment in important enablers such as infrastructure or financial support for R&D activities can mobilise private capital and improve the use and allocation of resources (European Investment Bank, 2022c).

Recent EU programmes offer insights related to the first point. EFSI achieved its goal of mobilising over €500 billion of investment, according to EIB estimates, using only €26 billion in EU budget guarantees and €7.5 billion of EIB own resources, resulting in a multiplier of over 15 (Wilkinson et al 2022).

Overall, the strategic investment programmes managed by the EIB have been successful in mobilising private investment using guarantees, loans, equity and quasi-equity instruments. However, it should be noted that most of the assessment of EFSI is based on analyses by the EIB itself. The EIB’s assessment of EFSI’s activities yield some insight on how the multiplier of 15.75 was achieved.

Some, though not all, project promoters that benefitted from EFSI support under its Infrastructure and Innovation Window (IIW) highlighted in particular that the EIB’s involvement in their project attracted other investors. However, promoters indicated that in some instances, EFSI financing might have crowded-out financing from other investors (Wilkinson et al 2022).

A survey of EFSI partners also indicated that EFSI operations led to improved availability and conditions of financing for SMEs and mid-caps, notably through increased lending activity to such firms at better conditions (lower collateral, fees, interest rates) by partnering lending institutions.

One in ten of respondents, however, reported that they could have obtained financing/guarantees at similar conditions from other sources without EFSI support. The EIB describes this level of redundancy as acceptable (Wilkinson et al 2022).

On the second point (increased corporate investment), given the relevance of SMEs in the European economy, the role of public investment in helping them increase their investments is particularly important. EIB analyses show that their loans translated to better financing conditions for SMEs and mid-caps, ultimately resulting in increased employment, investment and stronger growth of supported firms.

EIB (2022a) argued that their venture loans, which typically provide liquidity between rounds of raising equity in fast-growing firms, have helped lower financing costs and have crowded-in additional debt. The EIB estimates that alleviating financing constraints for EU firms could unlock €120 billion of corporate investment annually. Similarly, better infrastructure can lower the cost of doing business for firms and increase output.

On the third point, in addition to directly affecting the financing conditions for a project or company, EIB analyses indicate that EIB investment also has a reputational effect that can attract private investors.

Finally, public investment in infrastructure or research activities can generate additional private investment and improve productivity and the allocation of capital. European Investment Bank (2022c) projected that EFSI investment operations will have long-term positive effects on the EU economy, predominantly because of such structural effects.

The EIB makes use of financial instruments other than traditional equity and loans that can unlock private sector capital. Such instruments include intermediated loans, low-interest loans, credit enhancement, guarantees and venture debt. An important question is which financial instrument is most effective at crowding-in private investment.

Credit-enhancement products in particular have the clear potential to provide a high multiplier, ie. mobilising considerable investment by using a comparatively small amount of public resources. European capital markets are not as developed as in the United States.

Consequently, European companies have greater difficulty accessing risk capital than US counterparts. Furthermore, financing conditions for European firms might be deteriorating. The EIB Investment Survey (European Investment Bank, 2023b) indicated that the share of EU firms dissatisfied with the cost of finance in the EU increased from 5 percent in 2022 to more than 14 percent in 2023.

These factors increase the potential impact of public guarantees. In the future, research comparing different instruments in terms of cost and accessibility would be valuable in designing strategic investment programmes.

On the equity side, large infrastructure projects sometimes require an equity or quasi-equity buffer to make the project interesting for private investors. The public sector can play an important role in de-risking large-scale projects to attract private investors, including institutional investors such as pension funds and insurance companies.

The EFSI and InvestEU experiences show that equity and quasi-equity provided by the EIB has a positive effect for SMEs and mid-caps. Future ESI initiatives should explore the potential of such instruments to provide effective de-risking to projects.

5 Public investment management

5.1 Framework and examples

Improving the management of public investment is crucial in boosting the efficacy of public capital expenditure. Recent estimates indicate that roughly 30 percent of resources are lost in the process of managing public investment (Baum et al 2020).

Governments exhibit a relatively high level of inefficiency in deploying public investment, and Rajaram et al (2014) emphasised the range of reasons behind this phenomenon. The complexity of public investment projects, involving prolonged processes and presenting challenges in planning, coordination, financing, procurement and contract implementation, often results in cost overruns and delayed completion, surpassing even meticulously planned estimates. Baum et al (2020) estimated that inefficiencies could be halved through the enhancement of public investment practices.

Efficient public investment management across levels of government – regional, national and EU-level – is crucial for designing the future of ESIs. Insights from the public investment management can inform the ESI governance framework.

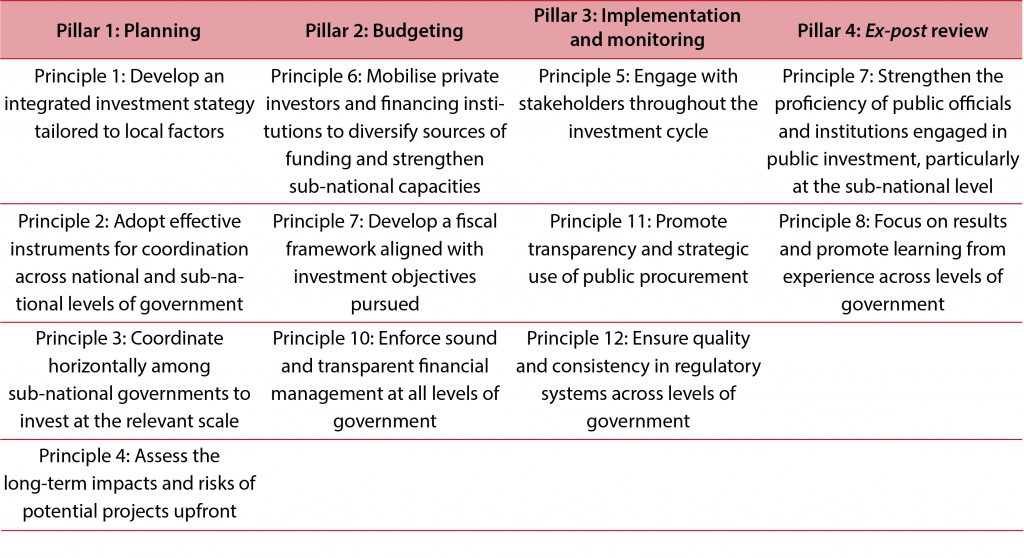

Based on this literature, we have identified four pillars for a well-functioning public investment system: i) planning, ii) budgeting, iii) implementation and monitoring, and iv) ex-post evaluation.

Underlying these four pillars are the ‘12 Principles for Action’ for effective public investment management across levels of government, published by the OECD in 2014 (OECD, 2014; OECD, 2019).

In 2015, the International Monetary Fund proposed its own framework to assess the quality of public investment management practices – Public Investment Management Assessment (PIMA; IMF, 2015).

The PIMA Framework focus is on the concrete planning of investments (with attention paid to coordination between the different policy levels), on allocating investment to the right project (based on transparent criteria and a long-term vision) and on implementing the selected projects within the set timeframe and within the planned budget.

Finally, Manescu (2022) provided fresh insights into public investment practices within the EU. The key elements highlighted for an ideal public investment system across various stages, as highlighted by Manescu (2022) include: planning, appraisal and selection, budgeting, monitoring and implementation, ex-post reviews and assets registers.

We highlight four pillars to enhance a public investment system, within which we classified the 12 Principles of the OECD:

Table 2. Fours pillars of public investment management

Note: Principles from OECD.

Source: Bruegel.

5.1.1 Planning

Governments should formulate robust investment plans based on a comprehensive, long-term strategy. These plans should include deliverables, accurate cost estimates, an assessment of existing capital assets and identified needs.

The objectives are to: i) design and implement investment strategies tailored to the specific locations they intend to benefit; ii) foster synergy and minimise conflicts between different sectoral strategies; and iii) encourage the production of data at the appropriate sub-national level to guide investment strategies and provide evidence for decision-making.

While most EU countries have some form of strategic investment planning, the extent can vary. Some examples of clear, multi-year investment plans can be found in the Netherlands (MIRT), Ireland (Project Ireland 2040) and Latvia (NDP27)20.

Coordination between different entities involved in a public investment effort is an essential aspect of success. Neglecting this can lead to misallocation of resources. In the Netherlands, a good example is the Association of Dutch Municipalities (Vereniging van Nederlandse Gemeenten, VNG), which unites all municipalities, and the Association of Provinces (Interprovinciaal Overleg, IPO) which coordinates between sub-national administrative layers.

In the UK, a Cities Policy Unit was created in 2011 with public, private, central and local stakeholders to help coordinate urban policy. The goal of the Cities Policy Unit is to work with cities and government to help cities create new ideas and turn the ideas into successful plans.

In Italy, the Interministerial committee for economic planning and sustainable development (CIPESS) is an example of efforts to minimise conflicts between different sub-national governments. CIPESS is responsible for the coordination and horizontal integration of national policies, and for aligning Italy’s economic policy with EU policies.

Finally, France has the Contrats de plan État-région (CPER), operational since 1982, which are important tools in regional policy in terms of planning, governance and coordination.

5.1.2 Budgeting

The second pillar refers to the importance of establishing a well-designed, stable and transparent medium-term budgetary framework that will ensure reliable budgeting for public investment. The goal is to promote consistency between annual budget decisions and the multi-annual lifespan of investment projects.

Additionally, involving private parties and financing institutions in investments can strengthen government capacity and bring expertise to projects, improving ex-ante assessment and achieving economies of scale and cost-effectiveness. Public-private partnerships (PPPs), enabled through innovative financing instruments, are ways of leveraging private capital that provides necessary scale and scope for investments.

The UK also utilises the Medium-Term Fiscal Framework (MTFF) to align budget preparation and public investment plans with fiscal policy. In France, key entities involved in public investment management include Bpifrance and Caisse des Dépôts et Consignations (CDC). Both institutions are tasked with investing in projects with policy goals and collaborating with the private sector.

5.1.3 Implementation and monitoring

Monitoring serves at least two related purposes: i) it can facilitate efficient capital allocation and, ii) it can identify potential problems early on and solicit remedial action. Good practices include the publication of monitoring reports, including reappraisal and termination options in project agreements, and defining and enforcing milestones.

Implementation is facilitated by ensuring consistent regulatory frameworks across the different levels of government involved. Furthermore, public entities should engage with a project’s stakeholders regularly throughout the investment cycle.

In France, the Secrétariat général pour l’investissement (SGPI) is responsible for ensuring the coherence and monitoring of the state’s investment policy through the implementation of the France 2030 plan. It is involved in the decision-making processes related to contracts between the state and investment management entities, and coordinates the preparation of project specifications and monitors their alignment with government objectives.

Moreover, it is responsible for the overall evaluation of investments, both before and after implementation. In the Netherlands, the Delta Programme represents a collaborative initiative involving the Ministry of Infrastructure and Environment, provinces, municipal councils and regional water authorities, working closely with social organisations and businesses.