Trump’s tariffs as fiscal folly

Kimberly Clausing is the Eric M Zolt Chair in Tax Law and Policy at the UCLA School of Law, and Maurice Obstfeld is C Fred Bergsten Senior Fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE)

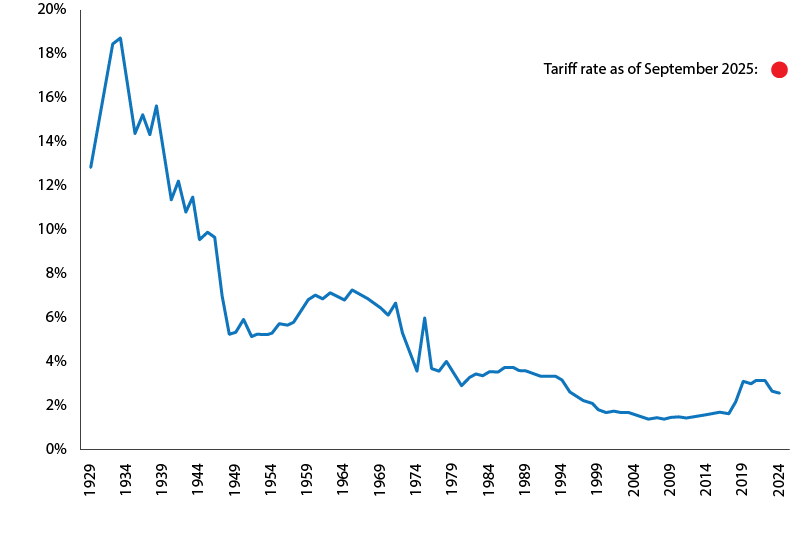

In 2025, the US government underwent a large fiscal switch. The US Congress enacted large income tax cuts, while the second Trump administration put new tariffs on goods at levels not seen in the US since the Great Depression. Such high tariffs are unheard of in the modern experience of most rich nations.

Typically, in high-income countries, tariff revenues account for a mere 1.25% of the value of goods imports and less than 2% of total government revenues1.

Figure 1. US effective tariff rates: Customs duties relative to total spending on goods imported, 1929-2025

Note: Actual revenues may be lower than those implied by this rate due to myriad exemptions.

Source: Data on customs and imports are from the US Bureau of Economic Analysis. The 2025 tariff is from Budget Lab (2025a).

While there are ample analyses of the first Trump administration’s China tariffs2 and detailed histories of the use of tariffs in the US (Irwin 2017), the full implications of the administration’s 2025 fiscal pivot will take time to unpack. In a recent paper (Clausing and Obstfeld 2025), we begin by evaluating tariffs as a broad tool of fiscal policy, reviewing both tax policy and macroeconomic considerations.

By these criteria, this fiscal switch will leave most Americans worse off. The negative distributional effects of tariffs are compounded by high efficiency costs, negative political economy consequences, and the twin macroeconomic pressures of negative supply shocks – upward price pressures and reduced economic growth.

While tariff revenues have burgeoned under the new Trump tariff policies, reaching about $30 billion per month in August 2025, several factors will determine the long-run revenue potential of US tariffs, including increasing rates of pass-through over time (as companies raise prices more if tariffs prove long-lasting), behavioural responses, tax avoidance, and the ability of firms to lobby for exemptions.

Other key considerations also reduce the fiscal benefits from tariffs, including mechanical reductions in other parts of the tax base (as tariff dollars cannot be simultaneously taxed elsewhere), payments to industries losing market share abroad (eg. farming), and the effects of reduced economic growth on the overall tax base.

There are also legal uncertainties regarding the President’s tariff regime. If the US Supreme Court backs lower court rulings that invalidate the President’s broad use of tariff authority under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) – as many legal scholars deem highly possible – that will reduce the administration’s flexibility in raising tariffs and is likely to substantially dampen tariff revenue. In 2025, most new US tariff revenues flow from IEEPA tariffs.

If such broad tariffs survive legal challenges, tariffs could net about $2 trillion in revenue over the coming ten-year budget window. While projected US tariff revenues are insufficient to pay for the tax cuts enacted as part of the 2025 budget legislation ($3.4 trillion over the budget window), they may prove hard for future US administrations to forgo, given the high current path of US deficits and debts3.

Still, potential tariff revenues are limited. Even if tariffs were levied at revenue-maximising rates, they would finance less than one-fifth of current US federal personal income tax revenue. Even tariffs at today’s rates come with serious downsides.

We calculate that tariffs have efficiency costs that approximate 30% of revenue raised at current (September 2025) US tariff rates, and efficiency costs would reach 90% of revenue raised at revenue-maximising tariff rates4.

Moreover, tariffs are a more regressive tax than the income tax, since poorer households save very little of their income in comparison with richer households. (While tariffs are less efficient than value-added taxes, they have similar distributional effects; saving is exempt from both taxes.) The 2025 tax and budget legislation (OBBBA) cut Medicaid and food assistance, generating negative income effects for the bottom three deciles of the US population.

While tariffs can be a useful tool for some circumstances in a rules-based system, the Trump administration’s ad hoc deployment of high tariffs against nearly every country in the world does serious harm to US international economic and political relations

The legislation has a further regressive impact overall because tax cuts are a higher share of after-tax income for households higher in the income distribution. The tariffs add to this regressivity, and they generate a negative net impact for most households. For all but the top decile of the US income distribution, tax increases from tariffs outweigh the gains from OBBBA tax cuts (Budget Lab 2025b).

In addition to their economic costs, tariffs create political dysfunction, as they encourage rent-seeking and corruption. Foreign governments, firms, and lobbyists seek better treatment than their competitors (through lower tariff rates or tariff exemptions).

Adding to the distortions, the Trump administration has levied tariffs in a highly coercive manner, forcing several foreign governments to offer unprecedented terms including promises of multi-hundred billion dollar investment funds that apparently would be directed by the Trump administration.

US tariffs have also been used as a punishment based on criteria completely divorced from trade. As just one example, the US levied a 50% tariff on Brazilian products due in large part to displeasure with the Bolsonaro prosecution5.

The current implementation of US tariff policy is haphazard and uncertain, adding both opportunities for rent-seeking and substantial unpredictability. In less than eight months (though end of August), more than 87 major policy developments have shifted the US trade environment (Bown 2025). At the same time, de minimis exceptions that streamline the customs treatment of small packages were abruptly ended, and complex new rules have complicated compliance.

These factors create administrative frictions that are particularly burdensome for smaller enterprises, and they raise costs for US importers and customs officials alike.

Supporters of tariffs may quibble with elements of implementation yet still describe the costs to households as ‘worth it’ to ensure two laudable aims: addressing US trade imbalances and increasing US manufacturing production and employment. Yet tariffs will not address US imbalances, since they do not address the root cause of the imbalances.

The US is a net international borrower, driven in large part by the large fiscal imbalances of the US federal government; US budget deficits now exceed 6% of GDP in a time of peace and full employment. So far, 2025 budget deficits are following a pattern that is nearly identical to those of 2023 and 2024 (Congressional Budget Office 2025), and the OBBBA will expand budget deficits relative to pre-OBBBA forecasts in the coming years.

Further, the Trump administration’s insistence that countries commit to larger foreign investment in the US, if effective, would increase trade imbalances by driving up the financial inflows that are the mirror of US current account deficits.

Although tariffs will reduce imports, they will also reduce exports through several channels. First, tariffs reallocate resources in the economy toward import-competing industries and away from export industries. All else equal, tariffs generate dollar appreciation which helps drive this reallocation6.

Second, exports are harmed by retaliation; the current plight of US soybean farmers is just one example of shirking markets for US exporters. Third, many US exports contain imported inputs, so tariffs raise input costs, generating negative competitiveness effects.

Beyond macroeconomic imbalances, the tariffs are also failing to lead a US manufacturing renaissance. This fact is unsurprising to those that studied past tariff episodes, including the China tariffs levied during the first Trump administration, which reduced job growth7.

US production in many industries has been harmed by disruption, uncertainty, and competitiveness shocks due to higher input costs. On net, the efficiency costs of tariffs will harm economic growth.

Ultimately, tariffs are a negative supply shock. Beyond harming output, they also generate upward price pressure, as both imports and goods that compete with them (or that use imported inputs) become more expensive. Upward price pressure takes time to propagate through the system for several reasons.

There was some import stockpiling before tariffs were levied, there are lagged effects of tariffs on intermediate goods, and some firms may be reluctant to raise prices until tariffs are more certain.

Indeed, there are serious uncertainties about the future path of tariffs, due to the mercurial nature of policy implementation as well as the strong possibility that the tariffs will be overturned by the Supreme Court. Still, tariffs inevitably lead to higher price levels, and the data indicate that this process is already underway.

In the end, the Trump administration’s use of tariffs is misguided. Combining income tax cuts with large tariff increases risks makes the tax system less efficient, less progressive, and more prone to political abuse. The Trump tariff regime also generates stagflationary headwinds and reduces goodwill with foreign partners.

While tariffs can be a useful tool for some circumstances in a rules-based system (for example, as a remedy or safeguard), the Trump administration’s ad hoc deployment of high tariffs against nearly every country in the world does serious harm to US international economic and political relations.

The underlying policy aims of tariffs, some of which are laudable, would be far better addressed through other tools. For instance, many other changes in the tax system can raise general revenue, the income tax system can redistribute income, and subsidies can encourage strategic industries, all at a lower efficiency cost than deploying tariffs.

Endnotes

1. Calculations are based on high-income OECD countries using import data from Harvard Atlas of Economic Complexity and tariff and tax revenue data from the OECD.

2. See Amiti et al (2019), Cavallo et al (2021), Fajgelbaum et al (2020a, 2020b), Fajgelbaum and Khandelwal (2022), Flaaen et al (2020), Houde and Wang (2023), Flaaen and Pierce (2024), Russ (2019), Russ and Cox (2020a, 2020b), Autor et al (2024), and Handley et al (2025).

3. Congressional Budget Office (2025b) estimates the budgetary impact of the 2025 legislation. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) also has a static estimate of revenue potential from tariffs of $3.3 trillion in Congressional Budget Office (2025c), higher than the $2 trillion we note here and close to the cost of OBBBA. However, as CBO notes, tariffs will shrink the size of the economy, which will lower this estimate; CBO also does not account for some of the other relevant considerations acting to lower revenues over time. We discuss the range of tariff revenue estimates more fully in Clausing and Obstfeld (2025).

4. Revenue-maximising tariff rates are about 43%, averaging results from the two import demand specifications in Clausing and Obstfeld (2025).

5. In contrast, the Milei government in Argentina, more kindred in spirit to the Trump administration, has been promised a “whatever it takes” financial bailout, although the terms and success of this bailout remain to be seen.

6. During 2025, the US dollar has broadly depreciated. This departure from the theoretical prediction likely reflects other factors that are operating at the same time, including retaliation, political attacks on the Federal Reserve’s independence, and a possible US economic slowdown. Still, econometric studies that control for macro variables suggest that tariff shocks typically lead to appreciation and little change in trade balances (Ostry et al 2025, Furceri et al 2020, 2021).

7. See sources in footnote 2.

References

Amiti, M, SJ Redding, and DE Weinstein (2019), “The Impact of the 2018 Tariffs on Prices and Welfare”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 33(4): 4.

Autor, D, A Beck, D Dorn, and G Hanson (2024), “Help for the Heartland? The Employment and Electoral Effects of the Trump Tariffs in the United States”, NBER Working Paper 32082.

Bown, CP (2025), “Trump’s Trade War Timeline 2.0: An up-to-Date Guide”, Peterson Institute for International Economics.

Budget Lab (2025a), “State of U.S. Tariffs: September 4, 2025”, The Budget Lab at Yale, 4 September.

Budget Lab (2025b), “Combined Distributional Effects of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act and of Tariffs”, The Budget Lab at Yale, 12 August.

Cavallo, A, G Gopinath, B Neiman, and J Tang (2021), “Tariff Pass-Through at the Border and at the Store: Evidence from US Trade Policy”, American Economic Review: Insights 3(1): 1.

Clausing, K and M Obstfeld (2025), “Tariffs as Fiscal Policy”, Peterson Institute for International Economics Working Paper 25-19 (forthcoming in National Tax Journal).

Congressional Budget Office (2025a), Monthly Budget Review, September 2025.

Congressional Budget Office (2025b), “Estimated Budgetary Effects of Public Law 119-21, to Provide for Reconciliation Pursuant to Title II of H. Con. Res. 14, Relative to CBO’s January 2025 Baseline”, 21 July.

Congressional Budget Office (2025c), “Budgetary and Economic Effects of Increases in Tariffs Implemented Between January 6 and May 13, 2025”, 4 June.

Fajgelbaum, PD and AK Khandelwal (2022), “The Economic Impacts of the US–China Trade War”, Annual Review of Economics 14(1): 1.

Fajgelbaum, PD, PK Goldberg, PJ Kennedy, and AK Khandelwal (2020a), “Updates to Fajgelbaum et al. (2020) with 2019 Tariff Waves”, 21 January.

Fajgelbaum, PD, PK Goldberg, PJ Kennedy, and AK Khandelwal (2020b), “The Return to Protectionism”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 135(1): 1.

Flaaen, A, A Hortaçsu, and F Tintelnot (2020), “The Production Relocation and Price Effects of US Trade Policy: The Case of Washing Machines”, American Economic Review 110(7): 7.

Flaaen, A, and J Pierce (2024), “Disentangling the Effects of the 2018-2019 Tariffs on a Globally Connected U.S. Manufacturing Sector”, The Review of Economics and Statistics.

Furceri, D, SA Hannan, JD Ostry, and AK Rose (2020), “Are Tariffs Bad for Growth? Yes, Say Five Decades of Data from 150 Countries”, Journal of Policy Modeling 42(4): 850–59.

Furceri, D, SA Hannan, JD Ostry, and AK Rose (2021), “The Macroeconomy After Tariffs”, The World Bank Economic Review 36(2): 361–81.

Handley, K, F Kamal, and R Monarch (2025), “Rising Import Tariffs, Falling Exports: When Modern Supply Chains Meet Old-Style Protectionism”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 17(1): 1.

Houde, S and W Wang (2023), “The Incidence of the U.S.-China Solar Trade War”, SSRN preprint, 8 May.

Irwin, D (2017), Clashing Over Commerce: A History of US Trade Policy, University of Chicago Press.

Ostry, D, S Lloyd, and G Corsetti (2025), “Trading Blows: The Exchange-Rate Response to Tariffs and Retaliations”, CEPR Discussion Paper 20452.

Russ, K (2019), “The Cost of U.S. Tariffs Imposed Since 2018”, Econofact, 11 October.

Russ, K, and L Cox (2020a), “Steel Tariffs and U.S. Jobs Revisited”, Econofact, 6 February.

Russ, K and L Cox (2020b), “The Trade War Has Cost 175,000 Manufacturing Jobs and Counting”, Econbrowser, 19 September.

This article was originally published on VoxEU.org.