The next steps for European economic security

Ignacio García Bercero is a Senior Fellow and Niclas Poitiers is a Research Fellow, both at Bruegel

Executive summary

The European Union’s economic security strategy was initially developed at a time of close transatlantic cooperation and focused largely on risks linked to Chinese dominance of certain parts of global manufacturing. However, given the diminished commitment of the United States to its traditional alliances and to multilateral rules, EU economic security planning now also needs to take into account the risk of US coercive action.

The EU must combine a medium-term strategy to reduce dependencies on both China and the US in critical areas with the capacity to react in the short term to threats of coercion. This requires supply chain chokepoints to be identified. There should also be a political discussion with EU countries on the circumstances in which the EU Anti-Coercion Instrument should be deployed, and the appropriate measures to respond to coercion.

The EU’s various tools for responding to urgent threats to its economic security need to be adapted to the new geopolitical context. The EU should prioritise support for research and development in relation to critical technologies and should ensure a more targeted and effective approach to state aid. It should avoid ‘buy Europe’ policies that contradict its international commitments and limit the scope for partnering with third countries.

On traditional economic statecraft tools, screening of foreign investment needs to be transformed to responding more effectively to economic security threats, while export controls need to be better coordinated. Given the need to de-risk relationships with both the US and China, strengthening economic partnerships has become ever more important.

Moreover, more robust governance structures to manage the use of economic security tools and partnerships with like-minded countries internationally need to be developed.

1 Introduction

In 2023, the European Commission published a European economic security strategy (European Commission, 2023a)1. It was conceived at a time when the European Union could rely on close cooperation with the United States and was part of a coordinated transatlantic response to the risk of the weaponisation of economic dependence by China. China’s dominant position in several manufacturing sectors, particularly in the processing of critical raw materials, was a particular focus.

EU-US alignment on economic security justified using the G7 as institutional platform to coordinate responses to economic coercion and, potentially, to develop economic security standards. On the EU side, the 2023 strategy is now being developed into an economic security ‘doctrine’ that focuses on how different policy tools can contribute towards mitigating economic security risks.

The move to a new economic security doctrine, in addition to EU initiatives on critical raw materials and on industrial policies, deserve a broader discussion on how to mitigate economic security risks in the new geopolitical environment.

The world has changed fundamentally (Sapir et al 2025). The administration of US President Donald Trump has shown little interest in coordinating action with allies when it comes to ‘de-risking’ relations with China. The US has even threatened the EU and its members with coercive action. This threat remains despite the EU-US trade deal inked in July 2025 envisaging cooperation on economic security2.

All of this is happening in the context of war on the European continent and the major threat from Russia. US weaponisation of economic interdependence, which was thus far mostly wielded in favour of common transatlantic objectives (Farrell and Newman, 2019), might now become detrimental to European interests. Meanwhile, China has shown its readiness to weaponise economic dependencies through its dominance of the processing of the critical raw materials relied on by EU manufacturing.

The 2023 EU economic security strategy triggered risk assessments in four areas3:

1. Supply chain vulnerabilities;

2. Critical infrastructure;

3. Technology security;

4. Economic coercion.

The strategy did not clearly define economic security but rather used economic security as an umbrella term for a collection of instruments (Chimits et al 2024). Such a lack of conceptual clarity could lead to confirmation bias or confusion about the instruments needed to respond to different types of economic security threat (Pisani-Ferry et al 2024).

Some ambiguity can be helpful in providing leeway when deciding on defensive action, but vague risk assessments can be problematic when trying to devise strategies to minimise risks. This implies that while it can make strategic sense to not be too tied down to reactive policies, proactive policies should be based on thorough risk assessments and definitions.

This is particularly the case for measures aimed at reducing supply-chain vulnerability, for which a balance is needed between industrial policies and foreign economic policies. Given the changing external threat environment, the EU economic security doctrine needs to be continuously reviewed and adapted. Since the economic security strategy was published, various steps have been taken as part of its implementation (Table 1).

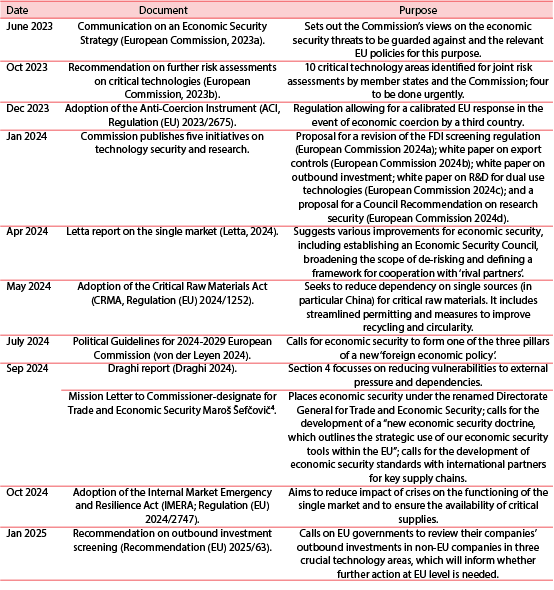

Table 1. EU policy developments on economic security since 2023

Source: Bruegel.

The challenge now is for economic security is to move beyond a process of risk assessments to risk-mitigation strategies based on the coherent deployment of economic security tools. The foundation for economic security policies has to be a clearly articulated view about the geopolitical positioning of the EU and the relationship between economic security and the EU’s overall economic strategy.

In this Policy Brief we assess the main threats to EU economic security (section 2) and then analyse and make recommendations on the roles of industrial policies, foreign economic policies and economic statecraft tools in mitigating the economic security risks facing the EU, and for the governance of economic security (section 3).

This is not to suggest that these instruments are the only tools for the mitigation of economic security risks. Horizontal policies that reinforce growth in the European economy, and notably underpin the single market and an open trade policy, are also critical enablers to promote economic security.

The move to a new EU economic security doctrine deserves a broader discussion on how to mitigate risks in the new geopolitical environment

2 The main threats to EU economic security

2.1 Import dependency

Overreliance on crucial imports is a clear risk to the EU economy. The ability of countries to restrict access to these imports strengthens their coercive power. Moves by both the US and China to restrict certain exports of chips5 and raw materials6 show this risk must be taken seriously.

A particular challenge is that a de-risking strategy for sectors such as the processing of critical raw materials requires close coordination among like-minded countries and substantial investment before dependency can be reduced significantly. An effective strategy to develop alternative sources of supply for critical raw materials, for example, would have to be structural in scope and implemented over the medium to long term7.

The 2023 European economic security strategy listed various ways to identify dependencies, such as stress tests, and the Commission has developed some metrics already. The Commission’s Joint Research Centre has published a set of economic indicators to capture the EU’s trade dependencies on third countries, broken down by exporting and importing countries and sector (Piñero Mira et al 2024).

However, both data and analytical challenges make identifying genuine import dependencies very hard (Mejean and Rousseaux 2024). It is difficult to measure substitutability, both intertemporally and cross-product. In other words, it is hard to know which products are genuinely critical to EU production or consumption.

Because of re-exporting and complex supply chains, it is also difficult to capture the EU’s ability to produce the products in question in the event of a shock, and to identify ultimate import and export dependencies8.

Broader import diversification is welcome, especially given the documented churn in the products for which the EU has dependencies (Vicard and Wibaux 2023). Detailed risk assessments and attempts to reduce dependencies should be limited to areas for which weaponisation would lead to greatest macroeconomic or social impacts.

There is broad agreement that de-risking is necessary for a narrow category of goods. These include semiconductors, batteries, critical raw materials and some pharmaceuticals (Pisani-Ferry et al 2024). These dependencies relate primarily to China (Figure 1).

The attitude of the Trump Administration means that areas previously overlooked must now also be considered. For instance, a thorough examination of critical defence dependencies should be prioritised (Burilkov and Wolff 2025; Mejino-López and Wolff 2025). Similarly, while energy dependence has generally been associated with Russia, EU dependence on imported liquified natural gas (LNG) from the US since the Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine should be considered a potential pressure point (Keliauskaitė et al 2025).

Beyond these categories, it is difficult to know exactly where to de-risk. Thus, engagement with the private sector in critical sectors is crucial, especially to identify upstream inputs for which there may be significant bottlenecks. Another important factor is that not all dependencies require the same policy response. For some, the EU might want to diversify imports (eg. LNG), whereas in defence, it could prioritise boosting European production or procurement from close allies such as the United Kingdom and Canada.

More importantly, the fact that many import dependencies can only be reduced in the medium term implies the need to develop strategies to deter coercive action in the short term. More attention should be paid, in close cooperation with member states and the private sector, to the identification of chokepoints based on reverse dependencies (ie. chokepoints under EU control), which could be targeted in attempted economic coercion.

Identifying such chokepoints may be critical if the EU Anti-Coercion Instrument (ACI, Table 1) is to be used in a targeted way – the ACI empowers the EU to react with a broad range of retaliatory measures should it threatened with economic coercion. In such cases, other measures may be more effective than import tariffs because affected countries may be able to diversify or simply absorb the tariff.

2.2 Export vulnerabilities

China has sought to apply economic coercion to the EU through restrictions on imports to its market (McCaffrey and Poitiers 2024). For example, Chinese attempts to sway member state decisions on the imposition of countervailing duties on Chinese electric vehicles included threats to limit access to the Chinese market for Spanish pork9 and French cognac10.

While such limitations are not macroeconomically significant, they have the potential to shape political outcomes. In the end, however, Chinese threats did not prevent the adoption by the EU of countervailing duties on electric vehicles11. But these types of threats might be more successful in areas in which the EU can only act on the basis of a positive qualified majority.

Understanding these risks is crucial. It is not always direct exposure that matters, as export restrictions may be applied further down the supply chain (China threatened to restrict imports of EU cars that contained parts from Lithuania in response to the opening of a Taiwanese representative office in Vilnius; McCaffrey and Poitiers 2024).

Such instances have helped firms understand that they may become casualties in this new geopolitical landscape, and firms seem to be diversifying supply chains and, in some cases, building secondary supply chains12.

The conclusion of new free trade agreements would make a significant contribution to diversifying export markets and could go together with tools to facilitate trade and the integration of value chains, such as negotiation with FTA partners of a common protocol on rules of origin or a supply chain resilience agreement.

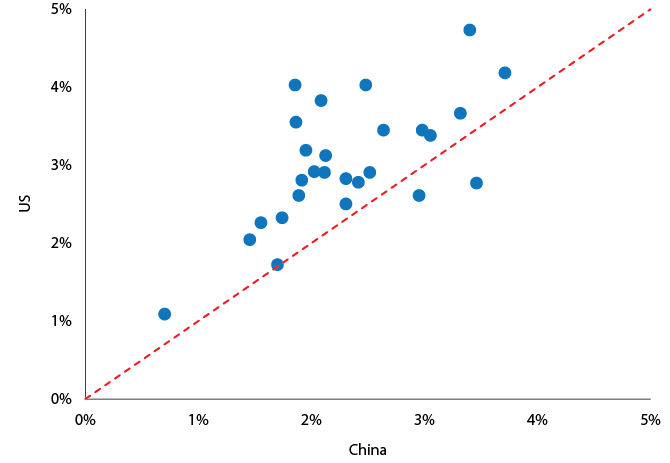

Figure 1. Dependencies of EU countries on US vs China (% of GDP, 2022)

Note: each dot represents a country and its position on an index that captures the “domestic gross value added generated by the exports of an economy to a trade partner directly and indirectly through third countries. This indicator is built up on domestic value added in exports and domestic value added in foreign final use” (Eurostat).

Source: Bruegel based on Eurostat trading partner exposure index.

2.3 Foundational technologies

The area of foundational and emergent technologies presents the strongest case for active industrial policies in the name of economic security. These are technologies with the potential to significantly disrupt and reshape the global economy.

A strong presence in the development of such technologies will help ensure the EU’s future strategic indispensability. In other words, the EU would be better equipped to hit back at the coercive measures of others and by doing so would change the decision-making calculus of would-be adversaries.

The semiconductor sector is a prime example. The EU does not control the fabrication of semiconductors, but, in ASML in the Netherlands, has a monopoly on the machines used for their production (Poitiers and Weil 2022b). This means the EU cannot be easily excluded from semiconductor value chains. On the other hand, allowing other economies to develop monopoly power in critical technologies would tie the EU’s hands.

The EU needs to protect its lead in the areas in which it maintains a significant edge, such as the ultraviolet lithography machines produced by ASML. However, given the scale and speed of developments in these sectors, it is equally important to play a pioneering role in the next generation of foundational technologies.

The EU previously held a dominant position in research and development in clean tech, before falling behind China (García-Herrero et al 2024). Eulaerts et al (2025) have identified emerging critical technologies using a range of techniques and these could be a solid basis for guiding future R&D support.

2.4 Financial and digital dependencies

Given US dominance in finance, there may be a risk of US financial coercion, not only trade coercion13. This was a feature of the first Trump administration when, for instance, pressure was put on HSBC over its interactions with Huawei, and on Swift to disconnect Iranian banks. Given the US desire to maintain the dominant role of the dollar and trust in its financial system, it is unclear exactly how far coercion in this sector could go.

However, the record of the first Trump administration and the actions of the second to date imply that this risk should be taken seriously. This is especially important given that finance did not feature in the European economic security strategy and, therefore, preparations in this area may justify a specific new risk assessment14.

The EU also relies on US digital services in many areas. The US tech giants often enjoy monopolistic power, and there are often few alternatives, apart from Chinese providers. This dependency is a potential EU weakness, especially when it comes to critical digital infrastructure such as cloud services and satellites15.

European attempts to break these US monopolies and compete in digital services continue to be significant sources of friction in transatlantic relations, resulting in US threats of trade restrictions as a response to the enforcement of EU digital regulations16.

The EU should, therefore, prioritise reducing its reliance on US digital infrastructure and finding the most effective responses to US threats. As with critical raw materials dependencies, reducing dependencies linked to US digital or financial dominance requires a medium- to long-term strategy and a combination of different EU tools.

3 The development of risk mitigation strategies

3.1 Industrial policies

Economic security is often presented as a justification for more proactive industrial policies, boosting domestic industry, particularly through state aid. Important Projects of Common European Interest (IPCEI) are the main EU-level tool for this. These are large-scale industrial projects using novel technologies and serving a strategic European interest, supported by public subsidies.

The European Chips Act (Regulation (EU) 2023/1781) follows this mould, as a more lenient sector-specific version of an IPCEI. It’s state-aid pillar uses the same R&D justification for state aid as ICPEIs and has the same conditionality, with the exception that it not only allows the promotion of completely new technologies, but also supports the introduction of technologies to the EU in the case of chip foundries (Poitiers and Weil 2022b).

For this type of industrial policy, there is a lack of clarity on the criteria for identification of industrial sectors for which an expansion of domestic production is both economically viable and necessary from an economic security perspective.

Whereas much of the focus has been on sectors for which there is an import dependency, not all import dependencies represent an economic security threat; in several sectors, diversification of import suppliers may be a better economic strategy. A better approach may be to subsidise R&D and its deployment in sectors that are at the technological frontier.

Moreover, IPCEIs have not been an unqualified success. Selection of individual large projects for significant subsidies has seen a number of notable failures. The Chips Act’s flagship project was to be a semiconductor factory in Magdeburg Germany, slated to receive €10 billion in subsidies.

Meant to promote European high-end manufacturing, the project was halted in 202417. Northvolt, a Swedish battery company that received significant ICPEI subsidies to build a battery supply chain independent of China went bankrupt in early 2025 (Tagliapetra and Trasi 2024).

ICPEIs are not the only policy tool intended to promote economic security by promoting investment in European strategic industries. The Critical Raw Materials Act (see Table 1) and the Net Zero Industry Act (NZIA, Regulation (EU) 2024/1735) introduce standards and procurement rules that seek to promote the diversification of European supply in sectors in which China has a market-dominating position (Le Mouel and Poitiers 2023; Tagliapietra et al 2023).

The main economic security tool under the NZIA has been the introduction of resilience criteria, sometimes combined with criteria related to sustainability or protection against cybersecurity risks. Resilience criteria require public buyers to diversify supply sources when procuring strategic technologies (ie. when the EU is dependent on a single supplier for more than 50 percent of its imports).

This approach needs to develop further. While the need to support certain industries through industrial policies (including subsidies) is clear, IPCEIs are not up to the task. The process of agreeing an ICPEI requires significant haggling between national government funders and large companies.

This favours established national industries over areas of import dependency, in which there is a lack of well-connected European industries. Furthermore, its use of an R&D state-aid exemption to support strategic industries makes the process onerous, while political pressure to approve projects under this narrow rule undermines the stringency of state-aid control (Poitiers and Weil 2022a).

Similarly, a better understanding of the problems that these policies try to solve is needed in order to design more targeted policies. The Chips Act’s emphasis is on foundries producing high-end chips but this does not address the causes of shortages during the pandemic and the EU’s strategic vulnerabilities relative to China.

The European Commission has also published work mapping the EU’s import vulnerabilities to its comparative production advantages, a valuable exercise that should help to inform when and how to implement industrial policies (Arjona et al 2023; Poitiers et al 2024).

Trade and Economic Security Commissioner Šefčovič has been asked “to develop economic security standards for key supply chains with our G7 and other likeminded partners” (see footnote 2). As discussed in section 3.4, it is not clear that the G7 is the relevant forum for developing such standards. There is also a need for greater conceptual clarity about the reasons for such standards. For instance, should such standards be met to benefit from certain incentives, or as a condition of market access? So far, the only standard with a clear economic security rationale is the NZIA resilience criteria.

In relation to consumption subsidies for green products or preferences for green procurement, the promotion of lead markets would argue for standards based on well-defined carbon-footprint and circularity requirements, which in cases of high dependency may be combined with resilience standards.

However, the risk of the emergence of an amalgamation of unrelated requirements to establish an ill-defined ‘economic security standard’ could lead to discrimination and protectionism.

One particular concern is the introduction in the EU’s February 2025 Clean Industrial Deal (European Commission 2025) of the concept of ‘Buy Europe’ or ‘minimum European content’, under which only products with a certain level of European content will benefit from access to government procurement or other benefits, such as consumption subsidies. Such policies would be incompatible with the EU’s international obligations and could also become a major obstacle to developing partnerships as part of the economic security strategy.

Moreover, the introduction of such criteria is not necessary to de-risk from China since China is not a member of the World Trade Organization Government Procurement Agreement and ‘resilience’ criteria will often be sufficient for de-risking purposes outside of government procurement. A ‘Buy Europe’ policy could be a major obstacle to partnerships with likeminded countries and for the diversification of supply chains.

A more coherent approach to the deployment of industrial and foreign economic policies for economic security purposes requires a multi-step analysis:

1. Identify the most economically significant economic security risks in terms of supply chain dependencies and risks in relation to critical technologies;

2. Conduct an economic assessment of the extent to which the EU has the capacity to increase production in the EU, or to maintain its lead or develop foundational technologies;

3. Identify the most effective tools to achieve the industrial policy objectives; and

4. Develop partnership strategies for the diversification of external supplies as the most cost-effective approach to reducing vulnerabilities.

The economic security doctrine should contribute towards better governance on the use of industrial policy and its interface with trade and other external policies.

3.2 Economic statecraft instruments

In certain instances, the promotion of economic security justifies the introduction of export or investment restrictions. These are the two most traditional economic statecraft instruments, use of which has intensified in recent years. In the EU, they are managed at member state level, though there have been ongoing attempts to reinforce EU coordination.

The EU has also adopted a specific instrument to respond to economic coercion: the Anti-Coercion Instrument (ACI; Table 1), which empowers the European Commission to retaliate against economic coercion with a variety of coordinated measures. To be triggered, the Council of the EU decides whether an instance of economic coercion has taken place. Once this decision has been taken, the European Commission has broad powers to retaliate against the offending country in a proportionate manner.

At the time of writing, the EU has not yet deployed the ACI, though Chinese responses to the EU countervailing duties on EVs or President Trump’s so-called reciprocal tariffs could have fallen within its scope. The unwillingness to deploy the ACI in circumstances of clear coercive threats raises serious questions about its credibility. The EU must be ready to deploy the ACI in case US threats of digital regulation materialise, or if China seeks to weaponise critical raw materials dependencies to influence EU decision making.

The identification of chokepoints and reverse dependencies is crucial in identifying possible response measures. The EU also needs to build the capacity to respond to possible escalation by the coercer. A discussion with EU countries should take place ahead of any invocation of the ACI to identify the appropriate tools to deter or respond to threats linked to digital regulation or the dependency on critical raw materials.

More broadly, the ACI should not be treated only a measure of last resort. The instrument allows targeted responses against measures or threats that seek to influence sovereign choices by the EU or its member states. Not responding to coercion would fundamentally weaken the EU as a geopolitical actor.

Another measure to protect European economic interests against foreign interference is screening of foreign direct investment. This is intended to protect strategic technologies from acquisition by potential geopolitical adversaries.

However, the European Commission plays only an advisory and coordinating role on FDI screening. EU governments decide themselves whether or not to block FDI, based on national-security concerns. The Commission has proposed reinforcing FDI screening (see Table 1) so that all EU countries have the capacity to screen investments in sectors that are critical for economic security; this would improve the coherence of investment screening.

The adoption of the Commission proposal (European Commission 2024a) is the minimum required to ensure adequate protection against risks of technology leakage, or relating to the protection of critical infrastructure.

The US has increased the use of export controls on dual-use technologies, particularly those related to semiconductors. China has introduced controls on critical raw materials exports, potentially causing major economic disruption. For the EU, greater coordination of export controls among member states is critical, in case escalating geopolitical tensions result in tit-for-tat export controls by the US and China.

The economic security framework should propose reinforced coordination of export controls at EU level, including an early warning mechanism under which the Commission and EU governments would be notified when a member state is considering the introduction of new controls.

3.3 Foreign economic policies

The two main foreign economic policies that can be deployed to reinforce economic security are trade policy and development cooperation policy. The EU’s vast network of free trade agreements (FTAs) is an essential tool to reduce export dependencies at time when the EU is vulnerable to the combination of US protectionism, and the Chinese focus on exports as the main source of growth.

Of particular importance are trade agreements with emerging economies that are both highly protected and have a substantial growth potential, such as the Mercosur bloc, India and Indonesia. It is also essential that the EU seeks to maintain maximum stability and predictability by leading a broad coalition that prepares the ground for World Trade Organization reform (García Bercero 2025).

Since WTO reform will take time, the EU should also seek ways to reinforce linkages between its bilateral trade agreements. This could be done, for example, through a common protocol on rules of origin, or closer cooperation with likeminded partners on supply chain resilience.

The EU could work with the members of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership as the starting point for such reinforced cooperation. To develop partnerships with third countries, inward-looking economic security policies should be avoided and support for rule-based trade must be maintained.

However, FTAs alone are unlikely to make a decisive contribution to the diversification of imports because WTO-mandated most-favoured nation tariffs for the areas in which the EU is highly dependent on China are often zero or very low18.

Moreover, FTAs and the WTO often have limited disciplines on export restrictions, or on issues relating to the business environment. Clean Trade and Investment Partnerships (CITPs) such as that signed with South Africa in November 202519 could fill this gap. To be successful, such partnerships should bring together all the relevant tools available to the EU to prepare balanced packages that are attractive to developing partners, including:

1. Identification of projects for which EU companies are ready to invest in the green value chain, including financial de-risking tools;

2. Rules relating to the business environment that address the main obstacles to investment in the country concerned;

3. An offer to provide technical cooperation and regulatory dialogue to facilitate compliance with European Green Deal regulations. This could include cooperation on carbon pricing or on the development of national deforestation plans, for instance.

CTIPs could be negotiated as self-standing agreements or in the context of broader FTA or investment facilitation agreement negotiations. For CTIPs to be effective, it is critical to have sufficient EU-level funding to support both financial de-risking and technical-assistance activities. This could be done through an ‘external partnerships’ window in the new Competitiveness Fund.

3.4 Governance of economic security

The implementation of economic security strategies raises a governance challenge. At EU level, there is a need to coordinate deployment of the various economic security tools, for which different parts of the Commission are responsible, and to ensure a robust framework for sharing information and for the coordination of EU and member state instruments. At international level, the relationship between WTO rules and economic security measures, and whether a new institutional framework is needed to coordinate economic security policies, must be clarified.

The creation of the role of European commissioner responsible for economic security was an important step towards better coordination of the work being done in the Commission, both on risk assessment and on ensuring synergy and coherence in the deployment of the different economic security tools. This would imply a reinforcement of cooperation between the relevant Commission services, with a coordinating role for the trade directorate-general.

At the political level, the Commissioners’ Project Group on Economic Security20 could steer work on risk-mitigation strategies and arbitrate in case of potential conflicts between services.

The Commissioners’ Project Group could perform two critical functions. It should agree on the prioritisation of economic security threats and should ask a lead service to coordinate the preparation of risk-mitigation strategies, based on contributions from all relevant services.

Prioritisation of threats should be based on a rigorous analysis of the risk of weaponisation of dependencies, and on the economically efficient means to mitigate such risks. In this context, the Commissioners’ group could seek an economic analysis from the Commission’s economic and financial affairs directorate-general.

Such risk-mitigation strategies should assess how all available tools that can contribute towards risk mitigation can be deployed coherently. These strategies should then be dis-cussed with member states to encourage consistency between EU and member state actions, and to provide a basis for a ‘Team Europe’21 approach to engage with third countries to develop de-risking partnerships.

At the working level, the Commissioners’ group should regularly update risk assessments and review cooperation activities with third countries. There should also be opportunities to consult the private sector when developing sectoral de-risking strategies.

In this context there may also be a need to develop instruments to gather the information needed to underpin economic security. This may require working more closely with those member states and economic operators present in priority value chains, to identify vulnerabilities that need to be de-risked. This work would be particularly relevant to identify reverse dependencies.

It is critical to fully involve member states in the assessment of risks, the development of risk-mitigation strategies and in seeking coordinated responses in areas of national competence, particularly when there is external pressure to align with the US. The Commission has already established an Economic Security Network to promote integrated advice from member states.

This should be reinforced (Steinberg and Wolff 2023; Letta 2024) through the establishment of a Council Working Group on Economic Security. The group should also evaluate policies relating to investments and export controls, on which most decisions are made at member state level. At the ministerial level, a Council meeting of ministers responsible for trade and industrial policies should be held once a year.

The WTO framework provides a basis for the development of economic security policies, even if there are gaps that should be clarified as part of a plan for WTO reform (Pinchis-Paulsen 2025; Pinchis-Paulsen et al 2024). The current rule book provides enough policy space for countries to adopt sanctions in the event of war or other emergencies, or to adopt measures to restrict investments or exports of dual-use technologies. WTO rules are, therefore, no obstacle for the use of traditional economic statecraft tools or sanctions in response to hard security threats.

The WTO rules on subsidies are also sufficiently flexible to accommodate policies that may need to be adopted for economic security purposes, though there may be a need to reinforce these rules to prevent their use to generate dependencies and to clarify when resilience criteria can be applied. In other words, economic security should not become a justification for adoption of WTO-incompatible measures.

The WTO does not at this stage provide a forum in which economic security policies can be discussed. There are also questions about whether the WTO dispute-settlement mechanism is the most appropriate tool to address conflicts arising from the implementation of economic security measures. The WTO framework could, however, be critical role in preventing tit-for-tat escalation by ensuring that any response to measures based on essential security concerns remains proportionate.

For instance, instead of reviewing the legal justification for export controls on dual-use technologies, an arbitration panel could establish the economic impact of the measures and review the proportionality of possible responses. All of these issues could be part of the discussion on WTO reform.

Beyond WTO, the G7 has been important for discussions on economic security. However, it is unlikely that the Trump administration would be ready to enter into a genuine process of consultation on economic security policies and measures. When the US might try to coerce other G7 members, it is difficult to see how meaningful any discussions in a G7 anti-coercion forum would be.

Nevertheless, there may be scope to cooperate on policies aiming at de-risking import dependencies in certain priority areas, such as critical raw materials.

In the absence of effective G7 cooperation, the EU could seek to reinforce bilateral dialogues on economic security issues with likeminded partners, notably the UK, Japan, Canada, Australia and South Korea. This could provide the basis for an informal group to coordinate policies on the de-risking of critical value chains and on responses to coercion.

4 Recommendations and conclusions

Our main policy recommendations arising from the analysis in section 3 are:

New economic security risk assessments should be started to evaluate risks associated with EU dependencies on digital and financial infrastructure;

The Commission should accelerate work on the identification of supply-chain choke-points, based on reverse dependencies;

Medium-term risk-mitigation strategies need to be developed for priority economic security risks, particularly related to dependencies on critical raw materials and digital and financial infrastructures;

The Anti-Coercion Instrument should be made ready for deployment in case threats related to digital regulation or export controls on critical raw materials are used as a coercive instrument;

The Commission should propose reinforced coordination on export controls, and the investment screening regulation should be reinforced based on the Commission proposal;

Any proposal to use industrial policy for economic security reasons should be preceded by a robust assessment of the economic security risks and an economic analysis that establishes the proper balance between industrial policies and foreign economic policies;

Measures inconsistent with the EU’s international commitments should be avoided;

The EU should include cooperation on economic security in its international trade and investment agreements, and should develop clean trade and investment partnerships as an instrument to support diversification of green value chains;

A new Council Working Group should be established to discuss priority risk-mitigation strategies and to attend, at least once a year, a ministerial-level discussion on the implementation of the economic security strategy;

At the international level, the EU should include discussions on economic security in its strategy on WTO reform, while coordinating policies with an informal group of like-mind-ed countries and negotiating a supply-chain resilience agreement with the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership.

The current geopolitical context implies that the EU needs to de-risk its relationships with China and the US, while facing a major hard security threat from Russia. This challenging environment makes it essential for the EU to develop broad alliances with countries that wish to maintain rules-based cooperation. The EU will need to stay decoupled from Russia economy for as long as it represents a threat.

The objective with China and the US should be to reduce dependencies while maintaining a maximum of mutually beneficial economic engagement. The extensive nature of dependencies implies the need for medium-term de-risking strategies, combined cooperation. However, the EU must also be ready to respond to threats of coercion.

Most economic security measures are preventive: an insurance policy to limit the risk of geopolitical tensions harming economic interests. In most instances economic security is not about responding to hard security threats, so it is essential to have institutional mechanisms that allow for the evaluation of trade-offs.

In particular, trade-restrictive economic security measures need to be balanced against the economic benefits of openness, or of achieving other essential EU objectives, such as the net zero transition. Whenever possible, win-win policies, including reinforcement of the single market, support for R&D, free trade agreements and support for green investment in developing countries, should be preferred over measures that restrict trade.

Endnotes

1. See European Commission press release of 20 June 2023, ‘An EU approach to enhance economic security’.

2. European Commission, ‘The EU-US trade deal: Restoring stability and predictability’, undated. Despite the EU-US trade deal, there have been US threats of tariffs as a response to EU digital regulation (see section 2.4).

3. Other economies have also introduced policies and strategies aimed at bolstering their version of economic security. See Chimits et al (2024) for an overview of different countries’ measures.

4. Mission Letter from Ursula von der Leyen to Commissioner-designate for Trade and Economic Security Maroš Šefčovič, 17 September 2024.

5. The US policy is evolving; see Michael Acton, Dimitri Sevastopulo and James Politi, ‘US scraps Biden-era rule that aimed to limit exports of AI chips’, Financial Times, 21 May 2025. See also Kana Inagaki, Sarah White, Ian Johnston and Ryan McMorrow, ‘Carmakers gear up for chip battle after China curbs Nexperia exports’, Financial Times, 17 October 2025.

6. See Ryan McMorrow and Dimitri Sevastopulo ‘China unveils sweeping rare-earth export controls to protect ‘national security’’, Financial Times, 10 October 2025.

7. A European Commission intention to produce a ‘RESourceEU plan’ is a recognition of this. See speech of 25 October 2025 by Commission President Ursula von der Leyen at the Berlin Global Dialogue.

8. For a more detailed discussion, see Mejean and Rousseaux (2024) and Pisani-Ferry et al (2024).

9. Thomas Hale, Joe Leahy and Barney Jopson, ‘Spain’s Pedro Sánchez calls on EU to “reconsider” Chinese EV tariffs’.

10. Edward White, Adrienne Klasa and Andy Bounds, ‘China targets EU brandy imports with anti-dumping penalties’, Financial Times, 4 October 2024.

11. Matt Geraci, ‘China’s lobbying did not block the EU’s new EV tariffs. But it may yet weaken them’, New Atlanticist, 4 October 2024, Atlantic Council.

12. See Economist Impact, ‘Trade in Transition 2025: Balancing optimism with caution’, undated.

13. Gillian Tett, ‘Dollar dominance means tariffs are not the only game in town’, Financial Times, 10 January 2025; Katie Martin, ‘Trump’s freewheeling disruption could extend to the dollar’ Financial Times, 20 February 2025.

14. Miran (2024) discussed using access to swap lines, which are a crucial tool for international financial stability, as an incentive to sign an accord that would force countries to accept a write-off on US government bond holdings. See also Elisa Martinuzzi, Jesús Aguado, Balazs Koranyi, Stefania Spezzati and John O’Donnell, ‘Exclusive: Some European officials weigh if they can rely on Fed for dollars under Trump’, Reuters, 24 March 2025.

15. For a discussion on satellites, see Alan Beattie, ‘Europe tries to fix its plumbing — and leave Starlink behind’, Financial Times, 20 March 2025. More broadly on digital services, see Fabry (2025).

16. Barbara Moens and Aime Williams, ‘Donald Trump threatens retaliatory tariffs after EU hits Google with €2.95bn fine’, Financial Times, 5 September 2025.

17. Michael Acton and Guy Chazan, ‘Intel outlines plans to cut costs and boost chip business in turnaround push’, Financial Times, 16 September 2024.

18. In the case of critical raw materials, see Le Mouel and Poitiers (2023).

19. See European Commission news of 20 November 2025, ‘EU and South Africa sign first-ever Clean Trade and Investment Partnership (CTIP)’.

20. See Decision of the President of the European Commission on the establishment of a Commissioners’ Project Group on Economic Security, 7 January 2025.

21. See Team Europe Initiatives website, European Commission.

References

Arjona, R, W Connell and C Herghelegiu (2023) ‘An enhanced methodology to monitor the EU’s strategic dependencies and vulnerabilities,’ Working Paper 14, Single Market Economy Papers, European Commission.

Burilkov, A and G Wolff (2025) ‘Defending Europe without the US: first estimates of what is needed,’ Analysis, 21 February, Bruegel.

Chimits, F, C McCaffrey, J Mejino Lopez, NF Poitiers, V Vicard and P Wibaux (2024) European Economic Security: Current practices and further development, In-Depth Analysis requested by the INTA Committee, European Parliament.

Draghi, M (2024) The future of European competitiveness, report to the European Commission.

Eulaerts, O, M Grabowska and M Bergamini (2025), Weak signals in science and technologies 2024, Joint Research Centre, Publications Office of the European Union.

European Commission (2023a) ‘European Economic Security Strategy,’ JOIN (2023) 20 final.

European Commission (2023b) ‘Commission Recommendation on critical technology areas for the EU’s economic security for further risk assessment with Member States,’ C(2023) 6689 final.

European Commission (2024a) ‘Proposal for a regulation on the screening of foreign investments in the Union and repealing Regulation (EU) 2019/452,’ COM(2024) 23 final.

European Commission (2024b) ‘White Paper on Export Controls,’ COM(2024) 25 final.

European Commission (2024c) ‘White Paper on options for enhancing support for research and development involving technologies with dual-use potential,’ COM(2024) 27 final.

European Commission (2024d) ‘Proposal for a Council Recommendation on enhancing research security,’ COM(2024) 26 final.

European Commission (2025) ‘The Clean Industrial Deal: A joint roadmap for competitiveness and decarbonisation,’ COM(2025) 85 final.

Fabry, E (2025) ‘Over-dependencies in services: A blind spot in the EU economic security strategy?’ in European Policy Centre, Turning the Tide: Towards Open Economic Security – Ten Reflections.

Farrell, H and AL Newman (2019) ‘Weaponized interdependence: How global economic networks shape state coercion,’ International security 44(1): 42-79.

García Bercero, I (2025) ‘How the EU should plan for global trade transformation’, Analysis, 21 May, Bruegel.

García-Herrero, A, H Grabbe and A Kaellenius (2023) ‘De-risking and decarbonising: a green tech partnership to reduce reliance on China’, Policy Brief 19/2023, Bruegel.

Keliauskaitė, U, S Tagliapietra and G Zachmann (2025) ‘Europe urgently needs a common strategy on Russian gas’, Analysis, 2 April, Bruegel.

Le Mouel, M and N Poitiers (2023) ‘Why Europe’s critical raw materials strategy has to be international’, Analysis, 5 April, Bruegel.

Letta, E (2024) Much more than a market, report to the European Council.

McCaffrey, C and NF Poitiers (2024) ‘Instruments of Economic Security’, in J Pisani-Ferry, B Weder Di Mauro and J Zettelmeyer (eds) Europe’s Economic Security, Paris Report 2, CEPR Press.

Mejean, I and P Rousseaux (2024) ‘Identifying European trade dependencies’, in J Pisani-Ferry, B Weder Di Mauro and J. Zettelmeyer (eds) Europe’s Economic Security, Paris Report 2, CEPR Press.

Mejino-López, J and G Wolff (2025) ‘Europe’s dependence on US foreign military sales and what to do about it’, Policy Brief 27/2025, Bruegel.

Miran, S (2024) A User’s Guide to Restructuring the Global Trading System, Hudson Bay Capital.

Pinchis-Paulsen, M (2025) ‘The Past, Present, and Potential of Economic Security’, The Yale Journal of International Law 50, forthcoming.

Pinchis-Paulsen, M, K Saggi and P Mavroidis (2024) ‘The National Security Exception at the WTO: Should It Just Be a Matter of When Members Can Avail of It? What About How?’, World Trade Review 23(3): 271–295.

Piñero Mira, P, S Banacloche Sanchez, J Rueda-Cantuche and F Montaigne (2024) ‘Macroeconomic globalisation indicators based on FIGARO’, Statistical Working Papers, Eurostat.

Pisani-Ferry, J, B Weder di Mauro and J Zettelmeyer (2024) ‘How to de-risk: European economic security in a world of interdependence’, Policy Brief 07/2024, Bruegel.

Poitiers, N and P Weil (2022a) ‘Opaque and Ill-Defined: The Problems with Europe’s IPCEI Subsidy Framework’, Bruegel Blog, 26 January.

Poitiers, N and P Weil (2022b) ‘Is the EU Chips Act the right approach?’ Bruegel Blog, 2 June.

Poitiers, N, S Tagliapietra, R Veugelers and J Zettelmeyer (2024) ‘Memo to the commissioner responsible for the internal market’, in M Demertzis, A Sapir and J Zettelmeyer (eds) Unite, defend, grow: Memos to the European Union leadership 2024-2029, Bruegel.

Sapir, A, JF Kirkegaard and J Zettelmeyer (2025) Geopolitical shifts and their economic impacts on Europe: Short-term risks, medium-term scenarios and policy choices, Report 1/2025, Bruegel.

Steinberg, F and G Wolff (2023) ‘Dealing with Europe’s economic (in-)security’, Global Policy 15: 183–192.

Tagliapetra, S and C Trasi (2024) ‘Northvolt’s struggles: a cautionary tale for the EU Clean Industrial Deal’, Analysis, December 11, Bruegel.

Vicard, V and P Wibaux (2023) ‘EU Strategic Dependencies: A Long View’, Policy Brief 2023- 41, CEPII.

Von der Leyen, U (2024) Europe’s Choice – Political Guidelines for the next European Commission 2024-2029.

The authors would like to thank Guntram Wolff for detailed comments and Connor McCaffrey for his excellent research assistance. This article is based on Bruegel Policy Brief No32/2025.