Is the post-war trading system ending?

Uri Dadush is a Non-Resident Fellow at Bruegel

Executive summary

The world trading system is reeling from the trade war between China and the United States, the disabling of the World Trade Organization Dispute Settlement Understanding and repeated rule-breaking by WTO members. This does not mean the end of the post-war system, but it is being transformed into a more complex, politicised and contentious set of trade relationships.

The new framework is likely to evolve around a WTO in maintenance mode with weak and largely unenforceable rules, and three blocs built by regional hegemons. Trade within the blocs will be relatively free and predictable, but the blocs are far from cohesive, contributing to the politicisation of the system. Trade relations between the blocs, especially among the regional hegemons, will be tense and potentially unstable.

Countries across the world need to rethink their trade and foreign policies to reflect the new reality. They need to continue to lend support to the WTO but also to accelerate work on regional and bilateral deals, while entering plurilateral agreements on specific issues – within the WTO if possible, or outside it if not.

Beyond these general prescriptions, the priorities of different economies vary greatly. The trade hegemons of China, the European Union and the US face vastly different challenges.

Middle powers on the periphery of the regional blocs, or outside them, such as Brazil, India and the United Kingdom, face an especially arduous struggle to adjust to a less predictable system. Small nations will be forced into asymmetrical deals with the hegemons or will play them off against each other, adding to the politicisation of trade relations.

The continued dysfunction of the World Trade Organisation (WTO) as a negotiating forum, the disabling of its dispute settlement mechanism, the trade war between China and the United States, and a proliferation of protectionist measures (Global Trade Alert, 2021) raise big questions: is the post-war multilateral world trading system, which enabled open and predictable trade, and which coincided with unprecedented economic progress, coming to an end?

If so, what will take its place? These questions are especially critical for the European Union, whose members are among the countries most dependent on trade, and which is multilateralist by virtue of its construction.

The future is unknown, but bad and good scenarios can be sketched out and their consequences examined. Bad scenarios require preparation and mitigation; good scenarios may present opportunities to be seized early on.

This Policy Contribution assesses how the trading system has changed over the last five years – roughly coinciding with the start of the Trump administration and one year of President Biden – and sets out scenarios for how the situation might evolve. Where possible, it derives some policy implications.

1 What constitutes the world trading system?

Much of the discussion of the trading system is cast in legal terms. Though essential, the legal perspective offers only limited insight into the economic effect of trade measures. Even the most egregious violation of WTO rules can have minuscule economic and systemic effects, while interventions that can be plausibly defended as legal can have far-reaching adverse consequences.

The enforcement of international law depends on the willingness of the most powerful sovereign nations to submit to it. So, it makes a big difference, for example, whether the rule-breaker is, say, Tunisia, or the United States – the principal architect of the post-war trading system.

Our interest here is not the number of violations of the rules, but their cumulative economic effect and what they imply for the sustainability of trade flows.

In that spirit, I depart from standard approaches in two ways. First, I define the world trading system as all rules and regulations governing world trade, including the WTO but also rules established under regional trade agreements and national law.

The WTO plays a central role in the world trading system because it is a near-universal treaty and it aims to govern the framework at all three levels, so members are obliged to fashion regional agreements and many domestic laws in a way that is WTO-compliant.

Though each regional trade agreement (RTA) comprises only two or a small group of partners, all RTAs together now cover most of world trade and often go much further than WTO disciplines. For example, while WTO agreements commit only to an upper bound for tariffs on most sectors, RTAs typically commit to zero applied tariffs on over 90 percent of trade. In 2020, nearly all EU members sent more than half of their goods exports to other EU members free of tariffs.

Domestic rules and regulations apply only in a single territory and are not enshrined in international treaties unless agreed explicitly. However, their coverage of commerce is comprehensive and detailed and can either promote or impede international trade in many ways.

Most disputes involving international companies are adjudicated in national courts, and rules and regulations governing trade in services, e-commerce and government procurement are still predominantly national or local. Thus, all three levels of law – global, regional, national – are crucial in determining the state of the world trading system.

Second, I depart from standard approaches by referring to ‘world trade’ or ‘international trade’ to include not only trade in goods and services but also foreign direct investment. The system of laws governing foreign direct investment is quite separate from that of trade in goods and services.

Investment protection is provided by bilateral investment treaties (BITs), while investment market access is governed by national laws and in some instances under regional trade agreements. The WTO’s coverage of foreign direct investment in goods remains minimal.

However, regardless of their legal separation, trade in goods and services and foreign direct investment have become inextricably connected through the globalisation of production, or global value chains. The locally procured sales of foreign subsidiaries are often larger than exports from a home base, and the lion’s share of services trade occurs under Mode 3 (foreign establishment/commercial presence). Therefore, any realistic assessment of the state of the world trading system must include restrictions on investment.

2 The system post-Trump

President Trump was elected on a nationalist and protectionist platform. On his third day in office, 23 January 2016, he abandoned the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a trade agreement that 12 nations, with the US leading, had negotiated over 10 years, but which had not been submitted for ratification by the US Congress.

Trump made numerous anti-trade and anti-WTO interventions subsequently, including tariffs on aluminium and steel on national security grounds applied to allies Canada, Japan and the EU, and, most notably, Section 301 punitive tariffs against China, starting in July 2018.

Trump also refused to renew the appointment of WTO Appellate Body judges, disabling it at the end of 2019. Though Joe Biden ran successfully against Trump on a platform highly critical of his trade policies, and has mended fences with the EU, he has shown little inclination to date to take a substantially different tack from Trump on China or on WTO dispute settlement.

As anticipated during his election campaign, Biden has declined even to consider new free trade agreements as he focuses on the pandemic and economic recovery.

There has been a major acceleration in bilateral and regional deals, and an improvement in their coverage and depth

The World Trade Organization

US dissatisfaction with the WTO long preceded Trump’s arrival. The failure of the Doha Agenda – initiated in 2001 – and the failure even to agree that it has died, means the WTO has not been able to move forward on a multilateral deal entailing major trade liberalisation.

The Trade Facilitation Agreement of 2013, which marked progress in establishing rules for custom procedures, is the only major achievement since the WTO was established in 1995. The last ministerial conference, held in Buenos Aires in 2017, ended without agreement.

COVID-19 has repeatedly forced indefinite postponement of the 2019 conference. During Trump’s tenure, the WTO was fundamentally damaged in two ways: the Dispute Settlement Understanding, considered the institution’s crowning achievement, has been disabled, meaning that rules are in practice no longer enforceable; and the outbreak of a trade war between the largest trading nations, China and the US, and the associated rule breaking, has undermined the WTO’s legitimacy and its prospects for reform.

The WTO contends with divisions among its members on crucial issues beyond China-US trade relations. These include a refusal of members such as India and South Africa to consider plurilateral deals as an alternative to the inoperable single undertaking/consensus procedure; opposition of China and India to the doing away of special and differential treatment for the best-performing developing economies; and the US refusal even to propose reforms of the Appellate Body that would assuage its concerns.

Despite the WTO’s dysfunction and the deep divisions over how to reform it, none of its members appear ready to leave or dismantle it. The EU remains strongly committed to multilateral negotiations and has been part of an effort, with China and about 40 other members, to establish an interim arrangement to settle disputes, using arbitration under Article 25 of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) while the WTO Appellate Body remains inoperable.

The Biden administration has departed from Trump by voicing support for the WTO. China has signalled in different forums that it will entertain structural reforms designed to allay concerns about its subsidies and other distortive measures (Dadush and Sapir, 2021).

China has joined negotiations on various ‘open’ plurilateral deals1, and has helped bring one – on domestic services regulation – to a successful conclusion. The WTO’s rule book, its acquis, continues to be valued by its members, giving it life despite the shortcomings.

Regional trade agreements

Since 2017, there has been a major acceleration in bilateral and regional deals, and, more importantly, an improvement in their coverage and depth.

RTAs notified at the WTO since 2017, or on which negotiations have concluded and are in the process of being ratified, include the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), accounting for over 13 percent of world GDP, and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (RCEP), which includes China and several Asian economies that are also part of CPTPP, and which accounts for 30 percent of world GDP.

Other notable deals include the United States, Mexico and Canada agreement (USMCA) which revises and extends the previous arrangement, and which also accounts for about 30 percent of world GDP, and the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), which accounts for about 3 percent of world GDP.

At least two important bilateral deals have come into force: EU-Canada and EU-Japan. Negotiations between the EU and Mercosur have been concluded but the deal faces major ratification obstacles, as does the innovative Comprehensive Agreement on Investment between the EU and China.

The number of RTAs in force notified at the WTO increased by a similar amount in the last five years as it did from 2011 to 2016: 68 in the latter period, compared to 61 in the previous one. Recently, several new agreements arose from Brexit and the subsequent rearrangement of the United Kingdom’s trade relations with third parties.

More important than the raw numbers, however, are the type and size of agreements that have been reached. After a fallow period from 2009-2010 in the wake of the global financial crisis (GFC), deals notified from 2011 to 2016 included no mega-regional agreements and consisted of relatively small bilateral deals. Australia-Japan and China-Korea were among the largest.

In contrast, recent deals including CPTPP and USMCA are ‘deep’ agreements encompassing large parts of world trade and containing important new WTO+ provisions on ecommerce, state-owned enterprises, subsidies, and labour and environmental standards.

The RCEP is a less deep agreement but includes harmonised rules of origin, which will significantly facilitate the operation of value chains across Asia.

AfCFTA should also be seen as a landmark agreement because it aims to integrate the market of Africa, the world’s poorest continent, home to many countries which took a sceptical view of the benefits of free trade after their colonisation by European powers ended some six decades ago.

Economists sometimes underestimate the importance of regional agreements, viewing them correctly as second-best to multilateral deals. Studies of regional trade agreements based on static simulation models typically identify only small net welfare gains accruing to the parties, even when agreements are large and comprehensive – less than 1 percent of GDP once and forever. They also indicate welfare losses in third parties as trade is diverted from them.

However, while these calculations are useful in many contexts, they fail to account for long-term dynamic gains from trade, such as those arising from competition and learning from the frontier. Most importantly, they use the status quo – ie. relatively free trade under WTO rules – as the counterfactual, which is precisely the assumption that ought to be questioned in the present circumstances.

For the United States, prior to USMCA, the last notified agreements were small and date back to 2012, when those with Panama, Colombia and Korea came into force. India has also stood back from major deals, dropping out of RCEP at the last moment, even as it resists all initiatives for WTO reform.

It is difficult to escape the conclusion that, faced with WTO negotiating dysfunction, India’s obstructionism and US opposition to the point of withdrawal from its adjudication function, nations worldwide have sought predictability in their trade relations elsewhere.

They are doing so by striking deals with their most important trading partners, even the most distant. If anything, this trend appears to have been reinforced recently, as shown, for example, by China’s and the United Kingdom’s applications to join the CPTPP2.

Domestic laws and regulations

The only source of regularly updated information on trade interventions that claims to cover domestic laws and regulations – as well as changes in tariffs – is Global Trade Alert (GTA)3 (Evenett and Fritz, 2021).

Drawing on various national sources, GTA reports 33,000 harmful rules (‘harmful interventions’) and 7,100 ‘liberalising interventions’ in the last five years, compared to 18,400 harmful interventions and 4,300 liberalising measures from 2011 to 2016.

Thus, harmful interventions have been four to five times more frequent than liberalising interventions, and the number of harmful interventions increased by 80 percent in the last five years compared to the previous five.

Only 7 percent of harmful interventions are tariff measures. Even before the pandemic, subsidies of various kinds that placed foreign producers at a disadvantage – whether at home or abroad – accounted for the vast majority of these measures. The remaining measures consist mainly of contingent protection and foreign-investment restrictions.

Contrary to the popular view, trade-distorting subsidies are frequent in manufacturing, and not just in agriculture, in violation of WTO rules. Moreover, though China is a major offender, so are the European Union and the United States.

It is difficult to characterise such a vast mass of interventions, but one can point to some important developments in the largest traders. For example, the US and the EU have adopted more stringent foreign-investment screening measures, especially those designed to guard against security risks and subsidised competition from China.

Under its Buy American Act, the United States has further restricted foreign access to its public procurement. China has stepped up various forms of control over foreign-invested companies, including in the political sphere – for example, by penalising firms that refuse to buy or produce in Xinyang4. However, its 2020 Foreign Investment Law introduced many important liberalisation measures.

3 Quantification

The previous discussion shows that large parts of world trade have become less open, most notably between China and the United States, the world’s largest economies. But it is also evident that other parts of world trade have become more open as huge regional deals have been struck.

At the same time, since WTO rules are no longer enforceable under the Dispute Settlement Understanding, all trade that is not covered by trade agreements has become less secure and predictable. While trade within the European Union, and that within USMCA, CPTPP and RCEP, to take four major examples, can rely on agreed enforcement mechanisms, trade that is covered only by the WTO cannot.

This is an especially ominous development because the world’s largest trading nations are by far the most reliant on WTO dispute settlement. No bilateral agreements exist between China, the EU, the US and India, for example. The smallest and poorest nations, in contrast, only rarely resort to the WTO to settle disputes5, though even the possibility that they can do so is a check on all members.

What is the net effect on trade flows of the restrictive and liberalising interventions that have been put in place over the last five years? This question could in theory be addressed in two ways: by estimating the tariff-equivalent effect of thousands of specific measures, or by examining the recent evolution of world trade against a counterfactual.

Unfortunately, without a major modelling exercise (and possibly not even then), neither approach can provide an unequivocal answer, based on the information and modelling techniques presently available.

Analyses of major interventions can shed some light, however (Box 1). The single most important restrictive event is the China-US trade war, which has resulted in additional tariffs of 20 percent on about $500 billion in bilateral trade.

Yet, China-US trade in goods accounts for less than 3 percent of total world trade in goods, and, according to Petri and Plummer (2020), the combined effect on global welfare of CPTPP and RCEP more than fully offsets the impact of the China-US trade war, though not for China and the US, which are net losers from the increased tariffs.

Box 1. Chronology of trade events

Note: From 2017 to 2020 the EU concluded FTAs with Canada, Japan and Vietnam, and concluded negotiations with Mercosur.

Estimates of US welfare losses from the trade war place them at around $50 billion, equal to just 0.04 percent of US GDP (Fajgelbaum and Khandelwal, 2021). And these losses are unlikely to have been offset by USMCA, which – though it contains innovative features – was essentially a revision of an existing agreement. As concerns openness to trade, the US is almost certainly in a worse place than it was five years ago.

In contrast, trade conducted by the EU is almost certainly somewhat freer than five years ago on account of its recent trade agreements. Brexit was a setback, but trade between the EU and the UK remains largely free under a revised framework.

Tariffs on EU exports of aluminium and steel to the US are now effectively lifted and replaced by a presently non-binding tariff rate quota arrangement (Dadush, 2021), and an agreement was struck in the long-standing Airbus-Boeing dispute6.

The tens of thousands of restrictive domestic measures listed by Global Trade Alert are certainly alarming. However, their quantitative impact is unclear. For example, GTA identifies thousands of subsidy interventions by the United States, most of them in manufacturing, identifying their source but not their size.

In fact, the two main sources of non-agricultural subsidies are the US Small Business Administration and the Export-Import Bank (Evenett and Fritz, 2021, pp 53-60). These organisations mainly dispense loans at preferential interest rates and their overall portfolios and budgets grew only modestly in the years preceding the pandemic. Accordingly, the grant element of net new loans and transfers dispensed by them is unlikely to be much above several billion dollars a year.

There is little doubt that these interventions break WTO rules (or at least depart from the spirit of non-discrimination) and their trade-distorting effect is significant for some firms in some sectors, but their quantitative impact on trade appears limited.

These partial analyses suggest that – except in the case of the United States and, possibly, China – trade for many nations, especially those in the Pacific rim, the EU and Africa, may be freer today than five years ago.

However, it is not possible to draw firm conclusions. What is the trade and investment deterrent effect, for example, of the uncertainties generated by the disabling of the WTO Appellate Body? And will this deterrent effect become magnified over time as trade disputes fester? These important research questions remain open.

If the cumulative effect of the restrictions applied over the last five years was large, it should be visible in the evolution of trade flows, in the form of a sharp reduction in the growth of world trade.

At this stage, it is not possible to say with any confidence whether or not this has occurred. World trade slowed sharply in the wake of the global financial crisis, well before Trump’s arrival. According to the International Monetary Fund World Economic Outlook (October 2021; Figure 1), over the last five years the volume of trade in goods grew at the average annual rate of about 2.8 percent, the same rate as the previous five years.

China-US trade, where one would be most likely to see the effect of protection, grew rapidly in 2021 from the pandemic-stricken levels in 2020. Although China-US trade is down from its peak in 2018, it is a little larger than in 2016.

Of course, there are significant confounding influences that prevent identification of the effect of protectionism on trade. In 2019, world trade stagnated reflecting a large slowdown in global economic activity arising from many factors unrelated to trade policy. The pandemic, which hit in early 2020, caused the biggest decline in world trade since the Great Depression, followed by a very sharp recovery.

Figure 1. annual growth of world GDP and trade volume of goods and services, % change

Source: Bruegel based on IMF World Economic Outlook Database, October 2021.

In any event, it is early days to gauge the effects of protectionist measures on global trade flows. Though the atmospherics of trade had deteriorated already in the run-up to Trump’s election, and markedly on the US withdrawal from TPP and with the levying of tariffs on aluminium and steel, major restrictive measures took effect only in 2018 with the Section 301 actions against China.

The WTO dispute settlement mechanism was known to be under threat even before Trump’s election, but it was disabled only at the end of 2019. Growth of trade in 2021 is still only an early estimate.

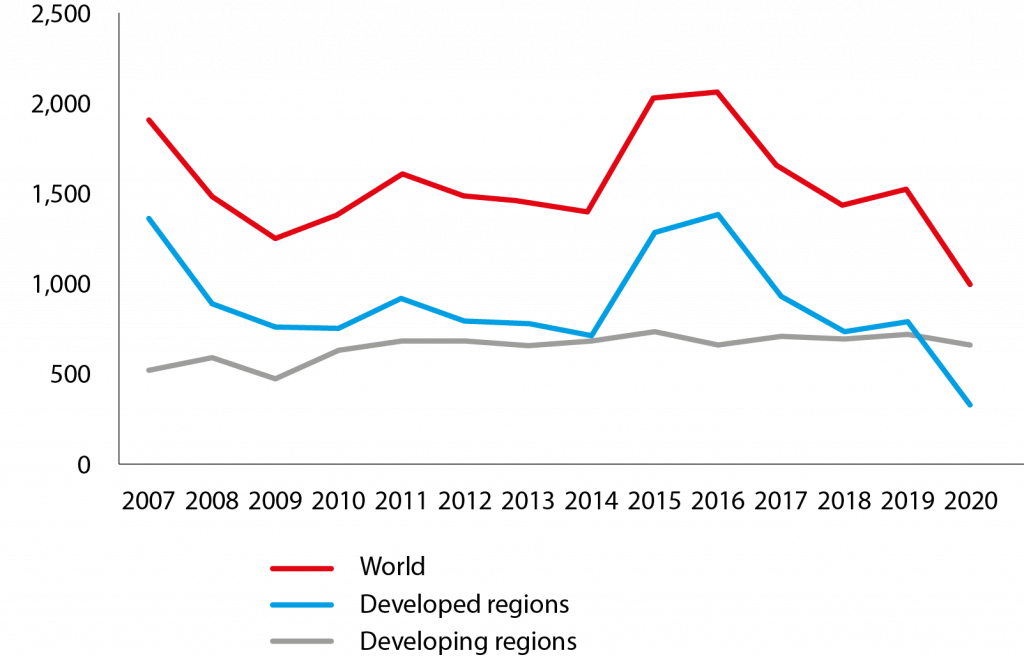

In 2021, world FDI had recovered from very low levels during the pandemic7. However, it remains about 20 percent below the level reached in 2016, on account of a decline in both inward and outward FDI in Europe and the United States, while flows of developing countries, including inward flows to China, have remained at similar levels as five years earlier. Despite the trade war, the US and China retain their ranks as the premier FDI destinations.

Figure 2. FDI inward flows for the world, developed and developing countries, $ billions

Source: Bruegel based on UNCTAD World Investment Report 2021.

In summary, some of the institutional underpinnings of world trade have been damaged, while others – mainly due to RTAs – have been strengthened in the last five years. Because of RTAs, the trade of the EU and Japan is probably freer.

US trade is almost certainly less free and trade among the largest economies has become less predictable as the crisis in the WTO has deepened. However, it is not possible to say with certainty whether the net effect of these big changes is to make trade across the world less or more restricted.

Though the headline average growth rate of world trade has not changed, it is also not possible to say whether, because of institutional changes, trade flows have slowed or accelerated relative to a counterfactual where institutional arrangements did not change. If anything, the evidence underscores the resilience of trade and foreign investment, even in very difficult circumstances.

4 Scenarios

Very bad and very good scenarios for world trade are both possible. However, the worst and best outcomes are equally unlikely. A more likely scenario lies in between (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Worst, medium and best-case scenarios for global trade relations

Source: Bruegel. Note: DSU = Dispute Settlement Understanding.

A worst-case scenario is conceivable, in which China and the US decouple, the WTO unravels, and the world descends into a dark age of protectionism, with declining world trade. There are two reasons to think it will not materialise: globalisation is not stopping, and countries are increasingly compelled to cooperate.

Countries that stand back from globalisation pay a heavy price in terms of foregone welfare and, ultimately, history shows, loss of international competitiveness and political legitimacy at home. Globalisation persists because vast arbitrage opportunities remain in the markets for goods, services and capital, and these opportunities are difficult to resist.

Arbitrage opportunities remain despite the global market integration of past decades because many developing countries, home to most of the world population, are growing rapidly and because product and process innovations continue.

Severe restrictions on migration (that do persist because they are supported domestically) imply that very large wage and price differences will remain. These can only be narrowed through trade and investment over a long time.

Meanwhile, ICT-based innovations, including remote work, e-commerce, artificial intelligence, blockchain and cryptocurrencies, are reducing trade costs, sometimes dramatically, by improving the ability to coordinate and exchange.

Meanwhile, globalisation itself and other factors that are largely extraneous to economic forces are greatly raising the stakes for international cooperation, of which trade is an essential part. Without trade in vaccines and personal protection equipment, there would have been many more COVID-19 victims, and economies would have struggled even more than they did to compensate for domestic supply disruptions. Mitigation of climate change and adaptation to it will be much more costly without open and predictable trade.

A best-case scenario, in which China and the US resolve their differences, WTO dispute settlement is reanimated, the WTO recovers its capacity to strike major deals, and MFN tariffs decline, is not impossible, but is also unlikely.

There is little reason to believe that the impasse on the big dividing issues at the WTO can be overcome, given the increased complexity of the issues confronting it, the diversity of its membership and the limitations imposed by its consensus rule.

The deepening geopolitical and security divide between China and the US adds greatly to the complexity (Dadush, 2022). Trade relations between the two giants are now less dependent on the technicalities of trade distortions than on geopolitics, and the prospects there are not good. Against that background and given its sharp political divisions on trade, the US does not appear likely to submit itself once again to binding adjudication in the WTO.

5 Prediction

The most likely scenario is a trading system based on trade blocs built around China in Asia, Germany/France in Europe, and the US in the Americas. Within the blocs, trade will be largely open and predictable -as presently seen within the EU and USMCA, for example – but none of the blocs are cohesive. Within each bloc, individual members – including the largest – will be attracted by the gravitational pull of large members outside the bloc.

The Asian bloc (built mainly around RCEP and CPTPP) is likely to remain the least cohesive, reflecting its many territorial disputes. Large Asian nations such as Japan must trade with China but also fear it, and are reliant on the US security umbrella.

India, protectionist and a rival to China, remains outside any of the blocs. The EU, a customs union and a single market in many respects, is the most cohesive trade bloc but because of divergent trade interests, internal divisions, and its reliance on the US security umbrella to contain Russia, it will struggle to define a trade strategy that accommodates both China and the United States.

The United States dominates in North America, but further south, Brazil and other nations, for which China and the EU represent very large export markets, are likely to chart a more independent course.

The WTO will languish in a kind of maintenance mode, as at present, but will not collapse. It will remain a reference framework, a forum for discussion and a purveyor of limited disciplines on international trade. Its weak and unenforceable rules mean that relations between the blocs will be tense, uncertain and potentially unstable, especially among the three regional hegemons.

Inter-regional disputes, such as those on aluminium and steel between the EU and the US, will proliferate and will be resolved in ad-hoc bilateral negotiations, or will simply fester when those fail. Outside the blocs, the absence of a binding adjudication process will lead to the politicisation of issues in many instances.

Many small and middle powers – ranging from the likes of Morocco to Brazil, India and the United Kingdom – will operate on the periphery of the blocs. In the event of trade disputes, they will be left with few defences.

These nations will be either forced into asymmetric deals with regional hegemons or will try to play the hegemons off against each other, adding to the politicisation of the trading system.

6 Policy

To deal with a world trading system based on regional blocs, and to guard against worst-case scenarios, countries should initiate or consolidate bilateral and regional deals with their main trading partners, including those outside their geographic regions. Where bilateral deals are not possible, countries should at least seek to establish regular consultation mechanisms.

These could prove useful not only to forge deals when the time is right, but also to avert disputes and, when a dispute occurs, to set up ad-hoc resolution procedures, such as arbitration.

Countries should continue to support multilateral and plurilateral initiatives in the WTO and should aim to re-establish the dispute settlement system in some form (eg. arbitration under GATT Article 25 as per the interim arrangement of which the EU is part).

However, they should also recognise the limitations of what can be achieved in that forum. Where progress stalls, countries should consider pursuing ‘closed’ or ‘open’ plurilateral deals outside the WTO.

Within this broad framework, policy priorities will vary depending on each country’s situation: a fertile area for further research.

EU members are already well positioned, since a large share of their trade occurs within the bloc and, as members of a customs union, they can rely on a vast network of agreements with third parties.

Some of these are high quality, deep agreements that go beyond trade in goods to cover services and investment. The EU’s main challenge is to develop a coherent trade strategy that captures opportunities in China while retaining strong links with the US.

The EU’s trade policy – like that of China and the US – will be heavily conditioned by geopolitics, so the deftness of the EU’s diplomacy will matter greatly in determining trade outcomes. The EU should revive the idea of a trade agreement with the US, perhaps a less ambitious deal than the ill-fated Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership.

The EU could also consider applying to CPTPP, as China and the UK have done, mainly in a quest to cement its links with all of East Asia, the world’s largest and fastest growing economy. The EU and China should seek a political compromise that enables ratification of the CAI.

China has continued to support the WTO and has complied with its rulings when found at fault. In recent years, China has also sought to negotiate numerous bilateral and regional deals, with considerable success. The size of China’s market and its dynamism provides it with a big advantage in trade negotiations, whether they are aimed at reciprocal opening or to avert and deal with disputes.

China’s ideal may be to build a free trade area covering Asia or even across the Pacific. But to do so, it will either risk suffering great losses in its most important export market, the US, or it will have to find a modus vivendi with its rival. Achieving that goal will require geopolitical and security compromises that go beyond the scope of this Policy Contribution.

In the narrow economic sphere, to reach a measure of agreement with the US, China will have to pursue structural reforms that limit the trade-distorting effects of its mixed economy. China will also have to recognise that, though it is a self-declared developing country, it bears major systemic responsibilities given its weight in world markets. China’s application to CPTPP is a step in the right direction.

The US is a special case because more than any other country it can – despite its diminishing sole superpower status – shape the world trading system as much as it must adjust to it.

A huge and diverse economy rich in human capital and natural resources, the US is the nation least forced to depend on international trade, but – because of its technological lead and the primacy of many of its firms in the fastest growing sectors – it is also that most likely to derive benefits from exporting and investing across the world.

More than at any time since the Cold War, its national security and the preservation of its alliances demand that it remains engaged in world trade.

The US faces a major choice: whether, as a nation of laws, it wants a world trading system based on rules, or one that is based on power. If it opts for the former, it will have to sacrifice some autonomy, but it is possible that some aspects of the good scenario described above will

materialise. The resuscitation of WTO dispute settlement is largely in the hands of the US, for example.

If – as appears more likely – the US opts for a power-based world trading system, it will retain more freedom of manoeuvre and will derive some advantages in the short-term, but it will also generate great uncertainty for its firms, antagonise its allies and may not retain its dominance for long as China rises.

Whichever path it chooses, the US must both expand its network of regional and bilateral trade agreements and seek a basis of understanding with China. Its current stance, which is to impede the WTO dispute settlement mechanism, cast China as the arch-rival and eschew all new trade agreements, is the worst of all possible courses.

Endnotes

1. ‘Open’ plurilaterals, such as the Information Technology Agreement, convey the benefits of the deal to all WTO members, whether they are participants or not, and do not require a waiver from the whole membership. They are possible when a critical mass of countries commits (ie. there are few significant free riders) and when the reforms they commit to are seen as promoting their own competitiveness. ‘Closed’ plurilateral deals, such as the Government Procurement Agreement, do not convey benefits to non-participants and typically do not include a critical mass of countries. However, under current WTO rules, closed plurilaterals require a waiver from the whole membership. No closed plurilateral deal waiver has been granted since the Uruguay Round.

2. See https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/uk-position-on-joining-the-cptpp-trade-agreement

3. See https://www.globaltradealert.org/

4. See Reuters, ‘China warns Walmart and Sam’s Club over Xinjiang products’, 31 December 2021.

5. Settling disputes at the WTO relies on the ability of the plaintiff to apply retaliation, which small and poor members tend to find ineffectual in a small market, or even impossible for the lack of alternative domestic suppliers. Moreover, the process is lengthy, expensive and requires legal capacity that may be lacking.

6. See for example France24, ‘US and EU reach deal to end 17-year Airbus-Boeing trade dispute’, 15 June 2021.

7. See Paul Hannon, ‘Foreign Investment Bounced Back Last Year but Did Little to Ease Supply Strains’, Wall Street Journal, 19 January 2022.

References

Dadush, U and A Sapir (2021) ‘Is the European Union’s investment agreement with China underrated?’ Policy Contribution 09/2021, Bruegel

Dadush, U (2021) ‘What to make of the EU-US deal on steel and aluminium?’ Bruegel Blog, 4 November

Dadush, U (2022) ‘Why the China-U.S. Trade War Will not End Soon’, Atlantic Currents, Policy Center for the New South, forthcoming

Evenett, S and J Fritz (2021) Subsidies and Market Access, the 28th Global Trade Alert Report, CEPR Press

Fajgelbaum, P and A Khandelwal (2021) ‘The economic impacts of the US-China trade war’, Working paper 29315, National Bureau of Economic Research

IMF (2021) World Economic Outlook Database: October 2021 Edition, International Monetary Fund.

Petri, PA and MG Plummer (2020) ‘East Asia decouples from the United States: Trade war, COVID-19, and East Asia’s new trade blocs’, Working Paper 20-9, Peterson Institute for International Economics

UNCTAD (2021) World Investment Report 2021, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development.

The author is grateful to Bruegel colleagues, especially Marek Dabrowski, André Sapir and Guntram Wolff, for useful comments. This article is based on Bruegel Policy Contribution Issue no04/22 | February 2022.