India’s commitment to renewable energy

Nirupama Soundararajan is the CEO, and Arindam Goswami a Fellow, at Pahle India Foundation

India has been committed towards alternative energy sources since early 2000. In 2002, renewable energy constituted a mere 3.2 per cent of total energy generation in India. However, by 2016 India’s focus on renewables paid off and the share of renewables to total energy increased to 42.6 GW from a mere 3.4 GW1.

The strong growth in share of renewable energy (RE) is testament to India’s continued commitment to the cause. India set an ambitious target of reaching 175 GW of renewable energy generation by 2022 in the 2015 Paris climate summit. Towards this end, India has introduced various policy measures.

India has initiated a two-pronged approach to tackle climate change issues. First is the National Action Plan on Climate Change (NAPCC) adopted on June 30, 2008, comprising of eight National Missions focussing on domestic issues and encompasses action plans in relation to different sectors interrelated to energy, industry, agriculture, water, forests, urban spaces, and the environment which are in line with the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

The National Missions are on Solar Energy, Enhancing Energy Efficiency, creating a Sustainable Urban Habitat, Conserving Water, Sustaining the fragile Himalayan Eco-system, creating a Green India through expanded forests, making Agriculture Sustainable and creating a Strategic Knowledge Platform for serving all the National Missions2.

The second is India’s Intended Nationally Determined Commitments (INDC) submitted to the UNFCCC on October 2 2015, which centres around sustainable lifestyle, cleaner economic development, reducing emission intensity of gross domestic product (GDP), increasing the share of non-fossil fuel-based electricity, enhancing carbon sink (forests), mobilising finance, and technology transfer and capacity building3.

As per India’s Ministry of New and Renewable Energy’s 2020-21 Annual Report4, as of January 2021, India’s installed RE capacity was at 92.54 GW, 24.53 per cent of total installed energy capacity. While India may miss her target for 2022 by an acceptable margin, her commitment towards RE remains ambitious and unshaken.

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s five core commitments, dubbed as the Panchamrit, or five nectar elements to deal with the global climate change crisis, at the recently concluded 26th session of the Conference of the Parties (COP 26) of the United Nations Climate Change Conference (UNFCC) garnered tremendous appreciation from the UNFCC members and from global media alike.

The five core commitments as promised by PM Modi include taking India’s non-fossil energy capacity to 500 GW by 2030, meeting 50 per cent of India’s energy requirements from renewable energy by 2030, reduction of the total projected carbon emissions by one billion tonnes from 2020 until 2030 by India, reduction of the carbon intensity of the Indian economy by less than 45 per cent, and become a net zero carbon emitting economy by 20705.

As part of India’s focus on RE, there has been an explicit thrust on electric vehicles (EVs), given the increase in vehicular numbers and congestion. India has a target of reaching 30 per cent share of EV by 20306.

While this is in line with India’s declared agenda for 2030 in COP26, this alone will not help. While EV will go a long way in reducing carbon emissions from vehicles, the incremental electricity load that will be required to run these vehicles would still predominantly be met through burning of fossil fuels.

A case study for New Delhi indicates that the incremental consumption of electricity could range between 755.4 MU to 1,762.6 MU assuming all households in Delhi own some form EV. Delhi’s monthly electricity generation as of 2019 was only 523.3 MU7.

The incremental electricity required for 30 per cent share of EV pan India is predictably immense, and since India is yet to put in place a suitable action plan to meet this electricity through renewables, it is imperative that alternative fuel sources are also considered to meet India’s 2030 targets.

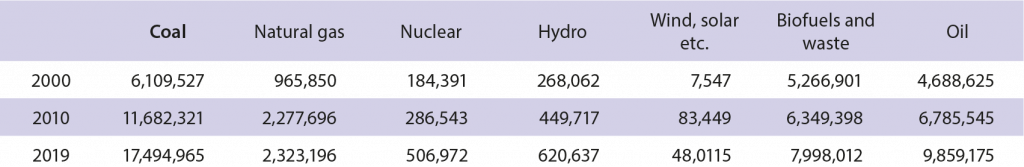

We know that one of the focus areas for the Government of India is to meet its COP26 objectives by reducing its dependence on fossil fuel, that is predominantly imported, and increase the uptake of non-carbon emitting fuel. Hence the increasing focus on biofuels (Table 1).

Table 1. India’s energy consumption mix

Note: All units in Terajoule.

Source: https://www.iea.org/

The National Policy on Biofuels (NPB) 2018 iterates India’s commitment to reducing fossil fuel use by concurrently increasing biofuel production and use. At present the Government of India has mandated the sale of ethanol blended petrol across the country except in the Union Territories of Andaman and Nicobar Islands and Lakshadweep.

The Government of India formally initiated the ethanol blending petrol (EBP) programme way back in 2003 when it considered supplying of 5 per cent ethanol blended petrol in nine states and four union territories (UT) in the country.

By 2008, blending of 5 percent ethanol with petrol was mandated in twenty states and four UTs with the further option of increasing the blend up to 10 percent of ethanol. The formulation of the National Policy on Biofuels in 2009 allowed ethanol to be procured from non-food feed stock like molasses, celluloses and lignocelluloses material including petrochemical route.

In 2013, oil manufacturing companies (OMCs) were directed to sell ethanol blended petrol with percentage of ethanol up to 10 per cent as per the Bureau of Indian Standard’s (BIS) specifications to achieve 5 per cent ethanol blending across India.

… one of the focus areas for the Government of India is to meet its COP26 objectives by reducing its dependence on fossil fuel, that is predominantly imported, and increase the uptake of non-carbon emitting fuel

The same year a decision was taken by the Cabinet Committee on Economic Affairs (CCEA) to procure ethanol only domestically and only from molasses and disallowed the usage of sugarcane and sugarcane juice as raw material. This had a negative impact on the supplies of ethanol.

Since 2014, the Government initiated reforms to boost indigenous production of ethanol. Some of these reforms over the years include reintroduction of administered price mechanism, opening of alternate route for ethanol production, amendment to Industries (Development & Regulation) Act, 1951 which legislates exclusive control of denatured ethanol by the central government, and reduction in Goods & Service Tax (GST) on ethanol meant for EBP Programme from 18 per cent to 5 per cent.

Notification of National Policy on Biofuels in 2018, which aims at mainstreaming of biofuel generated from non-food feedstock through next generation technology, explains the pledge towards climate change mitigation while enhancing energy security. The National Policy on Biofuels in 2018 aims to reach 20 per cent ethanol blending in petrol by 20308, which has subsequently been advanced to 2025.

Table 2. Annual world fuel ethanol production (million gallons)

Source: https://ethanolrfa.org/markets-and-statistics/annual-ethanol-production

Recently, an expert committee formed under the NITI Aayog submitted its report titled Roadmap for Ethanol Blending in India 2020-25 in July 2021 appraising the work undertaken by the Government in regard to the EBP. The Committee highlighted few of the steps which have worked for furthering EBP in India such as:

-Approval of the interest subvention for augmenting and enhancing ethanol production capacity by the Union Cabinet in December 2020

-Setting of standards for E5 (Ethanol 5 per cent, Petrol 95 per cent), E10 and E20 blends of EBP by the BIS

-Notification for adoption of E20 fuel as automotive fuel and issuance of mass emission standards for it by Ministry of Road Transport & Highways (MoRT&H) on 8th March 2021

-Notification for safety standards for ethanol blended fuels on the basis of Automotive Industry Standard (AIS 171) laying down safety requirements for type approval of pure ethanol, flex-fuel and ethanol-gasoline blended vehicles in India by MoRT&H on 25th May 2021

-Approval for BS-VI Emission norms for E20 Vehicles since 1st April 2020

The Committee pointed out that as a result of such efforts, the ethanol blending rose from 1.53 per cent during Ethanol Supply Year (ESY) 2013-14 to 7.93 per cent in ESY 2020-21. The Committee has further estimated that based on the expected growth in vehicle population of India, the ethanol demand till 2025 for achieving the goal of E20 will be 1,016 crore litres (10.16 billion litres) and has provided its recommendations based on the same.

To increase the ethanol production capacity, the Committee has recommended that the production of ethanol in India be raised to 760 crore litres (7.6 billion litres) from the existing 426 crore litres (4.26 litres) generated through molasses and 740 crore litres (7.4 billion litres) from the existing 258 crore litres (2.58 billion litres) generated through grain-based distilleries.

This, the Committee predicted will require 60 lakh MT of sugar and 165 lakh MT of grains per annum in ESY 2025. The Committee called for use of technology for production of ‘advanced biofuels’ from non-food feedstock.

On ethanol blending, the Committee recommends that pan-India availability of E10 fuel by April 2022 should be notified at the earliest and launch of E20 by April 2023, while additionally notifying all public and private sector OMCs to mandatorily join the programme.

The Committee also suggests formulation of specifications for intermediate blends such as E12 and E15. Literacy programme for consumers has also been suggested. Dispensing mechanism for various blends such as E10, E20 and E100 for two wheelers at retail outlets with lesser space requirements and logistical options for supplying ethanol all over the country have been suggested to augment infrastructure of OMCs.

Measures to expedite environmental clearances for producing ethanol, setting up a single window clearance for new projects for ethanol productions, and allowing unrestricted movement of denatured ethanol have been suggested to push the regulatory clearances for ethanol producing units.

Production of higher ethanol compatible vehicles, incentives for ethanol blended petrol vehicles, pricing policies of ethanol blended gasoline, and ways to encourage use of water saving crops to produce ethanol have been some of the other recommendations.

However, it is important to put things into perspective in terms of production and in terms of impact. First, we know that 10 million litres of blended fuel is supposed to reduce 20,000 tonnes of carbon emission9.

As per India’s COP26 targets, India plans to reduce carbon emissions by one gigatonne or 1 billion tonnes10. A basic calculation therefore suggests that if India manages to meet the ethanol demand target of 10.16 billion litres by 2025, this would result in a reduction of 0.10 billion tonnes of carbon emissions, which can barely be considered even as dent even these figures were to be extrapolated for 2030.

Clearly India needs to step up the targets of EBP. Hence purely from an impact point of view, the current EBP targets are a far cry from India’s larger 2030 objective of reducing carbon emissions.

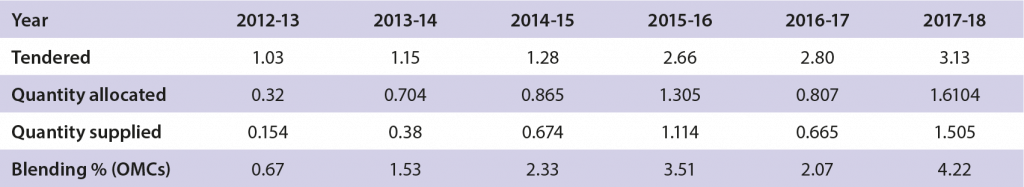

Second, it is apparent from Table 3 that the quantity supplied has almost always been less than the quantity tendered/contracted, and the quantity allocated. While phenomena like droughts, and issues like storage capacity can be listed as causes for some part of the difference in quantities, they do not explain the large discrepancy and inconsistency in supply figures.

Table 3. Ethanol supply, procurement, and blending (figures in billion litres)

Source: ‘Note on Biofuels’, Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas, 2019. http://petroleum.nic.in/sites/default/files/biofuels.pdf

Inconsistency in supply of ethanol will lead to uncertainty with regard to meeting blending targets, whether in 2022 or 2030. Part of the problem may also be that the primary feedstock for ethanol in India currently are molasses and the move to explore other sources of feedstock have been once recent. This has also been a common criticism of the ethanol blending programme11.

Alternative feedstocks for ethanol would be those from second generation (2G) pathways, such as biomass and agricultural waste with high cellulosic and lignocellulosic content that can be converted to ethanol using 2G technologies.

These are precisely the feedstocks that the NPB seeks to tap into, as the NPB notes “studies undertaken in India have indicated a surplus biomass availability to the tune of 120-160 MMT annually, which, if converted, has the potential to yield 3,000 crore litres (30 billion litres) of ethanol annually.”12 This is the path the government should opt for.

Third, in 2021 India’s domestic ethanol production was 820 million gallons or 3.1 billion litres13. In the same year, India’s total imports for ethanol was 750 million litres14. Around 25 per cent of domestic production, is being met through imports.

Ironically, India’s largest import partner is China. This does not behove India. India clearly has the capability to use domestic feedstock to meet the demand for ethanol. It makes even less sense to import from China given India’s own tumultuous relationship with the country.

India’s ethanol programme is crucial to India’s growth and self-reliance. The ongoing Ukraine-Russia standoff has already resulted in spiralling oil prices upwards. Even if India does consider procuring excess oil from Russia, it would come at the cost of jeopardising relations with other important trading partners including America and United Kingdom.

India has always had the intention of reducing her dependence on crude oil, first for economic reasons (as a way to control the current account deficit), then for environmental reasons, and now more than ever for geopolitical reasons.

Endnotes

4. Annual Report 2020-21 | Ministry of New and Renewable Energy | India (mnre.gov.in)

6. NITI Aayog, RMI, and RMI India, Banking on Electric Vehicles in India: A Blueprint for Inclusion of EVs in Priority Sector Lending Guidelines, January 2022.

7. Box 3.2, pg 34, “Reforms Required to Spur Investment in Mobility”.

8. National Policy on Biofuels, 2018, Ministry of New & Renewable Energy, Government of India

9. Pg 5, https://static.pib.gov.in/WriteReadData/specificdocs/documents/2022/feb/doc202222720201.pdf

12. ‘Para 5.10.2’, National Policy on Biofuels, The Gazette of India: Extraordinary, (June 2018): p. 17.

13. Conversion of 1 US liquid gallon = 3.78 litres

14. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1052223/india-ethanol-import-volume/