Broader border taxes in the EU

Pascal Saint-Amans is a Non-Resident Fellow at Bruegel

Executive summary

There is widespread agreement on the need for new resources to fund the European Union’s budget in order to meet increasing spending demands, not least repayment of debt incurred as part of the EU’s post-pandemic economic recovery.

In particular it is seen as desirable that the EU should have ‘own’ resources, or reliable ongoing revenue streams. But there is little agreement on what new own resources could consist of.

Limited reform so far has led to the introduction of a levy paid by EU members depending on plastic packaging waste generated in their territory and not recycled. Meanwhile, the European Commission has proposed resources for the EU budget from emissions trading revenues, and from levies collected under the EU carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM). There proposals are pragmatic and move in the right direction, but do not go far enough.

The debate about own resources should focus on whether the EU will be able to build genuine own resources based on common tax policies. The EU suffers from ‘tax leakage’ in which profits are shifted from high-tax to low-tax EU countries, and from there onto no or low-tax non-EU jurisdictions, often without the application of withholding taxes.

It may not be too much of a stretch to compare this situation of tax leakage with the situation addressed by CBAM – a quasi-tax at the border. So far, an opportunity for what could be seen as a tax at the border of the internal market, aiming to protect the market from harmful competition, may have been missed.

Such a tax could reflect the undertaxed profit rule agreed as part of the international deal on the corporate minimum tax. Focusing on protecting the revenues of EU members by common tax borders could offer scope for new own resources.

1 Introduction

While the budgets of its member countries are funded primarily by taxes approved by their parliaments, the funding of the European Union budget is much more complex, reflecting in part the ambiguous nature of the EU. The Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union provides that “without prejudice to other revenue, the budget shall be financed wholly from own resources” (Article 311).

‘Own resources’ are ongoing streams of revenue mainly collected by member countries and passed onto the EU, with EU governments responsible for deciding by unanimity what these resources should be.

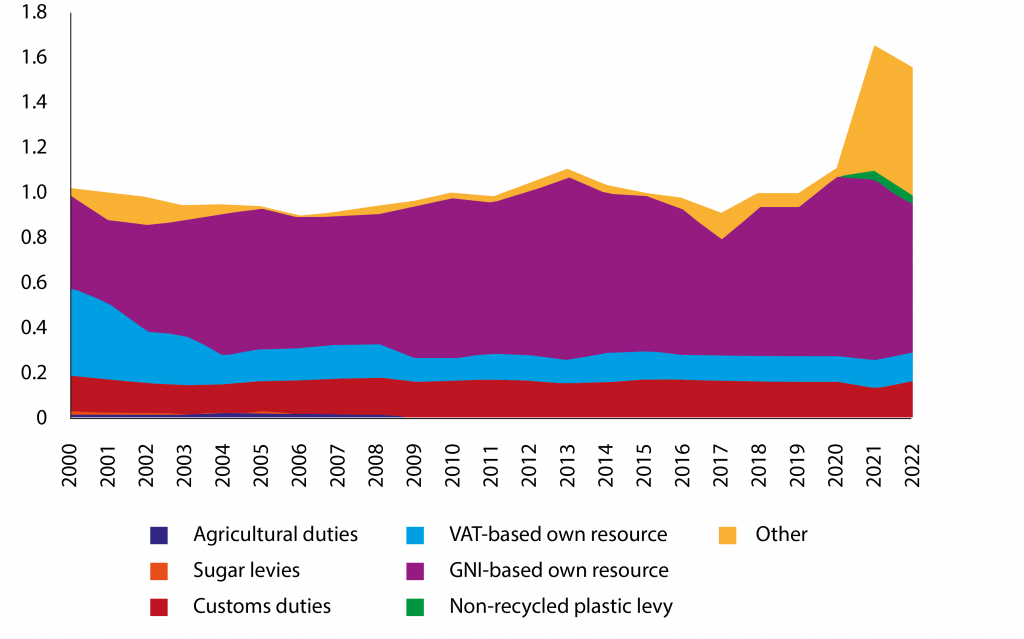

Consequently, revenues for the EU budget comprise a mixture of so-called ‘genuine’ own resources (levies that belong to the EU, such as custom duties) and other contributions from member countries, usually based on statistical aggregates, like value-added tax and gross national income (GNI)1. The latter have significantly increased over time and represented almost three-quarters (72 percent) of the EU budget in 2020 (Figure 1; for pre-2000, see European Commission, 2021).

Figure 1. Sources of financing for the EU budget (% of EU GNI)

Note: Borrowing to finance NextGenerationEU is included for 2021 and 2022, reflected in the large increase in the ‘Other’ category. This category also includes smaller sources of revenue such as fines, surplus from the previous year and revenue from EU policies.

Source: Bruegel based on European Commission.

‘Genuine’ own resources now account for a small portion of the overall budget, which is a good illustration of why the EU needs a new approach to funding its activities. The adoption in December 2020 of the EU’s post-pandemic recovery programme NextGenerationEU (NGEU), allowing debt financing for the first time in European Union history, was an opportunity to reopen the debate on own resources.

Also in December 2020, an EU Inter-Institutional Agreement2 on the EU budget provided that “The repayment of the principal of such funds to be used for expenditure under the European Union Recovery Instrument and the related interest due will have to be financed by the general budget of the Union, including by sufficient proceeds from new own resources introduced after 2021.”

On 14 December 2020, the Council adopted a new own resource – on non-recycled plastic waste – for the first time in years, as if a new era was beginning. The European Commission then proposed, in December 2021, three new own resources:

1. Contributions from the EU emissions trading system (ETS);

2. Contributions from the carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM), which is designed to equalise the carbon cost of certain goods, whether produced inside the EU or imported;

3. A share of the revenue expected from the application of an Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development agreement on the taxation of the residual profits of large multinational companies.

Though endorsed by the European Parliament, this proposal failed to trigger much discussion among EU countries. In June 20233, the Commission tabled a revised proposal for ‘An adjusted package for the next generation of own resources’ (European Commission, 2023a).

As well as setting out new ideas for revenues, the proposal called on EU countries “to accelerate the negotiations”, with the objective of getting a unanimous decision by 1 July 2025 for the introduction of the new own resources in January 2026.

The question is what such new own resources should be, and particularly, whether it is possible to identify additional ‘genuine’ own resources with a European character – as opposed to statistically-based contributions such as VAT and GNI shares, which encourage thinking about the EU budget in terms of net balances received or contributed by member states (Fuest and Pisani-Ferry, 2020).

Before assessing the Commission’s proposal, one can only note the lack of appetite among EU countries to move this debate forward. In February 2024, an agreement among EU countries on a midterm review of the EU’s seven-year budget (the Multiannual Financial Framework, MFF) gave only a cursory mention to new own resources, with no update on the position of member states on the Commission’s proposed package4.

The purpose of this paper is two-fold: first, to review the Commission’s revised proposal in the context of the new financing challenges resulting from NGEU, and second to contribute some new ideas for ‘genuine’ own resources.

We find that the Commission has taken a pragmatic approach aimed at speeding up the negotiations, rather than revisiting the nature of the own resources. As to new ‘own resources’, we offer some recommendations that draw on recent progress on international taxation.

2 Background: the impact of NGEU on the EU budget and its financing

In adopting NGEU, EU countries called for a revision and expansion of the EU’s own resources, to finance the borrowing costs for the approximately €421 billion in NGEU grants and to reduce reliance on the GNI-based own resource (Council, 2020).

They also agreed to raise the maximum potential amount of their annual contributions to the EU budget by an additional 0.6 percent of GNI, expressly for the purpose of servicing NGEU interest and debt.

For the first time in decades, a new resource based on non-recycled plastic waste, was adopted and entered into force in 20215. However, this new resource is relatively small money compared to the debt service required for NGEU, contributing only about 3 percent of total EU revenues (European Commission, 2023b). Moreover, it is not an EU levy, but is based on contributions from members, reflecting their levels of non-recycled plastic packaging waste.

With the first repayments of NGEU borrowing due in 2028, a timeline was agreed to revisit this issue and find new resources. The December 2020 Inter-Institutional Agreement provided that “the expenditure from the Union budget related to the repayment of the European Union Recovery Instrument should not lead to an undue reduction in programme expenditure or investment instruments […] It is also desirable to mitigate the increases in the GNI-based own resources for the member states.”

In absence of an agreement on additional own resources, the burden of financing this debt will fall directly on EU countries through the increased ceiling, leading to an even greater reliance on the GNI-based contribution to the EU budget. It could also translate into cuts in current programmes to make room for debt service.

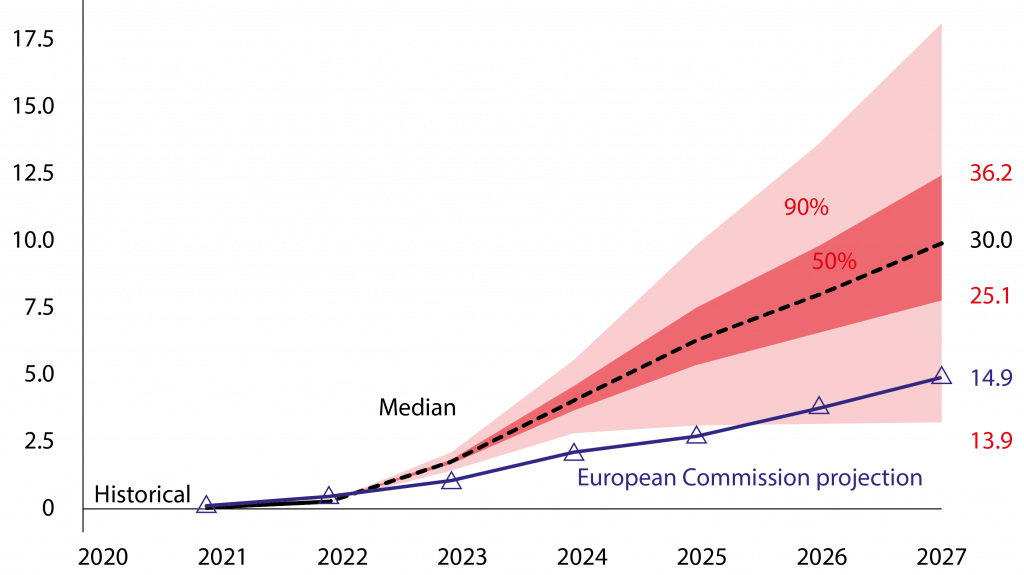

The Commission has already had to propose changes to the current MFF to respond to the much higher-than-expected interest rates on EU borrowing costs (Figure 2)6. Hence, the debate on increasing own resources is critical to EU-funded policies.

Figure 2. Projected annual and total interest costs borne by the EU (in € billions)

Source: Claeys et al (2023a).

3 The European Commission proposals on own resources

3.1 The initial Commission proposal of December 2021

A first package of three new own resources was proposed by the European Commission in December 2021 (European Commission, 2021). This package introduced what could be considered ‘genuine’ own resources, with 25 percent of the emissions trading system (ETS) revenues and 75 percent of carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM) revenues going to the EU budget.

CBAM, which would levy a border toll (the Commission refrains from using the word ‘tax’) on certain carbon-intensive imports, entered into force in October 2023 and will become a definitive system in 2026. It will not be a significant revenue raiser.

However, CBAM shares some similarities with custom duties as it is an EU levy at the point of entry of goods into Union territory. The ETS, meanwhile is clearly an EU-wide policy and, even though revenue can be tracked nationally, with most of the revenue allocated to each member state, the over- all approach remains an EU approach.

The Commission’s proposal was therefore to rebalance own resources away from contributions from member states, whether based on VAT or GNI, and towards EU policy-based resources.

The third element of the December 2021 proposal related to the potential revenue generated by the agreement reached at the OECD on the reallocation of taxing rights among more than 140 countries to some of the profits of the world’s largest and most profitable companies.

This was the culmination of an issue debated for more than a decade in the context of the idea that market jurisdictions were not receiving fair shares of revenues from the world’s biggest digital companies. While the OECD negotiations on a global approach progressed slowly, some EU members, led by France, pushed for the introduction of an EU digital services tax (DST), which failed to obtain unanimity in 2019.

Some members introduced domestic DSTs from 2018 to 2021, while the OECD was still negotiating a multilateral solution within its Inclusive Framework on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (bringing together 140+ countries7). In July 2020, EU countries agreed that, in the case of a failure of the OECD negotiations, a tax on digital companies would be agreed and would be an own resource.

In 2021, the Biden Administration rebooted the negotiations, which resulted in a two-pillar agreement at the OECD. Pillar 1 provides that a quarter of the rent (defined as the profit above a 10 percent profit margin on sales) earned by the largest and most profitable multinationals (above €20 billion in revenues and 10 percent profitability) would be allocated to market countries (countries where the goods or services are sold) using a formula based on sales, whether or not the company is physically present in the country.

This is a significant departure from traditional transfer pricing rules and a move towards what economists call ‘destination’. Interestingly, Pillar 1 would not be limited to tech companies, as was initially asked for by most European countries.

The Commission’s December 2021 proposal proposed that 15 percent of the revenue accruing to EU countries from the Pillar 1 taxing rights reallocation would become an own resource.

The rationale behind that reallocation seemed to be more reflective of a political mood (‘taxing the digital economy’, or “taxing the GAFA” as the French finance minister repeated, in Council throughout 20188, even though the scope of the OECD agreement had already broadened) than about building a genuine own resource, as could have been the case with the initially planned DST.

The proposed rate of 15 percent was hard to explain (at the global level, the reallocation of profit for taxing has been projected to be in the range of €150 billion).

Pillar 1, however, is subject to the development of a multilateral convention, which would require ratification by all signatories, including the United States, with a two-thirds Senate majority. The development of the multilateral convention is running late, with a new deadline in June 2024 for signing, and very uncertain prospects for ratification.

Interestingly, the Commission did not propose anything on own resources in relation to Pillar 2 of the OECD agreement, which provides for the establishment of a global minimum tax of 15 percent on the profits of multinationals with revenue above €750 million.

The expected additional tax revenues globally from this pillar are higher (in the range of €200 billion), with a complex three-tier mechanism that might be interesting from an EU own-resource perspective. We return to this issue in section 4.

In proposing new own resources, it was wise for the Commission not to go back to the idea of a European digital services tax

3.2 The revised European Commission package

The Commission’s June 2023 “adjusted package for the next generation of own resources” (European Commission, 2023a) added to the December 2021 plan in three ways: an increased slice of ETS revenues for the EU budget, a change to the date when some supplementary ETS revenues would start to flow into the budget, and a proposed new own resource related to corporate profits.

The EU budget share of ETS proceeds would increase from 25 percent to 30 percent, with no change related to CBAM. As the carbon price has increased, this would still leave more revenue to member states (€46 billion per year from 2028) while securing an annual €19 billion for the EU budget. CBAM, meanwhile, would be expected to generate €1.5 billion as of 2028 for the EU budget.

The June 2023 proposal formally maintains the 15 percent contribution deriving from the OECD deal, despite that deal’s uncertain prospects of implementation.

In addition, the Commission proposed a new statistical-based resource on company profits. This was described as a “national contribution calculated on the basis of statistics from national accounts under the European system of accounts”, a proxy for company profits.

It would be less of a genuine own resource than CBAM and ETS contributions. It is also a pragmatic reflection of the fact that an EU harmonised tax on company profits is still a distant prospect.

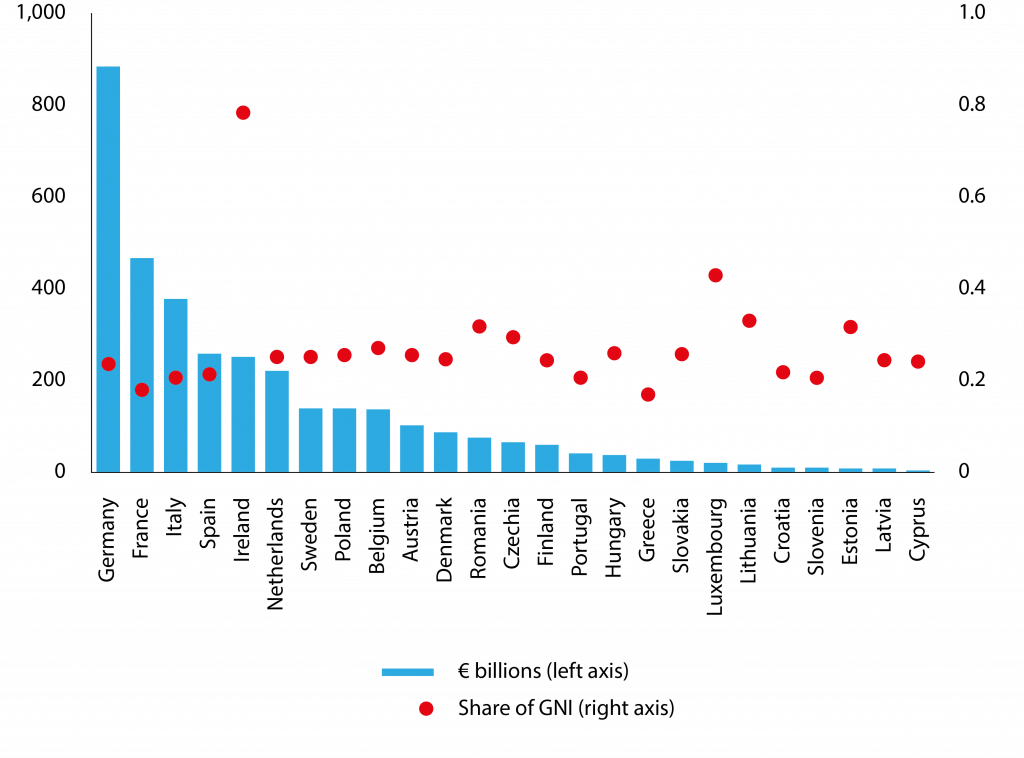

The Commission estimates the base of corporate profits could reach €3 trillion and trigger revenues from €3 billion to €16 billion per year, with a call rate of 0.1 percent to 0.5 percent. The proposed resource has merit in that it would increase the absolute contribution of the largest and most advanced EU members (Germany, France), while having the largest effects in terms of GNI on smaller members that have benefitted from decades of corporate profit shifting (predominantly Ireland and Luxembourg; Figure 3).

While the ETS own resource could disproportionately penalise some Eastern European countries (because of their shares of electricity generation from fossil fuels), this new resource would balance the contribution back to the ‘west’.

Expected amounts from the resource would be broadly comparable with €19 billion from ETS/CBAM. Finally, this resource is presented as temporary: it would be superseded by a share of taxes on corporate profits based on a common European tax base for corporations, which the European Commission is pushing for9.

Figure 3. Gross operating surplus for corporations by country in € billions and as a share of GNI, 2021

Note: Gross operating surplus data is unavailable for Bulgaria and Malta.

Source: Bruegel based on AMECO.

The new statistical based resource on company profits is one of eight potential new own resources, most of them previously mentioned by the European Parliament10 and scanned by the Commission. This ‘scanning’ exercise against three selection criteria (revenue potential, simplicity in terms of compliance and administrative burden and fast mobilisation) was brief and could look like lip service to seven potential new own resources11.

3.3 An evaluation of the Commission proposal

The Commission’s revised proposal is pragmatic and moves in the right direction, but does not go far enough.

First, the Commission rightfully puts the emphasis on ETS revenue, increasing the allocation to the EU budget from 25 percent to 30 percent. As demonstrated by Fuest and Pisani-Ferry (2020), ETS revenues fit best the criteria for EU budget resources: “carbon emissions do not primarily cause damage where they occur […] additional emissions in a particular member state should be regarded as negative externalities in other member states […] emission reduction objectives are set at the EU level.” As the authors concluded, “ETS allowances are not that different from custom duties”, making them genuine own resources.

In addition, potentially big revenue can be derived from the ETS. Since the Commission’s December 2021 proposal, the EU carbon price has increased significantly. The price per tonne of CO2 was until recently above €90 and likely to rise further in the mid-term, much higher than the price assumption of €55 for the period 2026-2030, as presented in the Commission’s legislative proposals related to the 2030 emissions reduction target of minus 55 percent compared to 1990.

Not only has the price increased, but the scope is also broadening, with a second ETS (ETS 2), which covers buildings and road transport, becoming operational in 2027. This dynamic allows the Commission to increase the EU share of ETS revenue from 25 percent to 30 percent, while leaving net increased revenue to member states at €46 billion per year from 2028.

The only downside to this approach may be of a political nature. Carbon pricing remains unpopular when directly borne by households, which is why the allocation of ETS 2 revenue was politically committed to social compensation and redistribution, rather than financing EU own resources.

Allocating part of ETS 2 to policies not directly related to greening the economy represents some political risk that the Commission and other EU institutions must be mindful of.

It will be important for the Commission to assure people that money collected from ETS 2 will be spent on climate objectives to alleviate the burden on households of the energy transition. It may make political sense to allocate the revenue to funding green policies and not divert it to other actions.

Second, the Commission is right to maintain its proposal to allocate 75 percent of CBAM revenues to own resources. Logically all resources arising from CBAM should in fact be allocated to the EU budget, but it was politically impossible for the Commission to not leave 25 percent of CBAM revenue to member states.

The Commission estimates that €1.5 billion from CBAM would accrue annually to the EU budget from 2028. This however would depend on the reaction from the main impacted EU partners. Some may adopt pricing policies, which would reduce CBAM revenues.

This would remain good news as the overall policy objective is about emission reductions and not revenue. In any case, CBAM is not where the bulk of revenue is. In the long run, when decarbonisation occurs, the fundamental question of finding a more stable revenue base will arise.

Third, the new statistical based resource on a proxy for corporate profits can be considered a smart move. It does not rely on the fast adoption of BEFIT, the latest Commission proposal on harmonising corporate income tax in the EU. Whatever the merits of BEFIT, the prospect of adoption is extremely low given how difficult the corporate income tax debate has been in Europe for decades.

More importantly, it is wise for the Commission not to go back to the idea of a European digital services tax (DST) as a substitute for the OECD deal, notwithstanding that, in July 2020, EU governments recommended the adoption of a European DST in case of OECD negotiation failure12.

DSTs are taxes on transactions, which would be a proxy for EU countries to tax the profits of tech companies that leave very little profits on their territories because of aggressive tax planning that takes advantage of the inadequacy of existing international tax rules.

DSTs may seem like a good idea but to the extent that they are taxes on gross income, they would create double taxation, would be borne by consumers more than companies, and would likely generate trade tensions with the US.

For all these reasons, they are divisive and an EU DST is unlikely to garner the necessary unanimity to be adopted. By not mentioning this option, the Commission risks of being criticised by DST advocates (France, Italy, Spain), but spares itself a difficult and unpromising negotiation within the EU and tensions with the US.

While it adds little to the December 2021 proposal, the adjusted Commission proposal can be defended as a pragmatic move to facilitate a discussion of own resources with member states within a constrained calendar.

European elections are approaching, and a Multilateral Financial Framework proposal will have to be tabled by 2025, while the strategic agenda will have to be approved in 2024. With the first repayments of NGEU debt in 2028, EU institutions are running out of time.

4 EU taxation ideas worth of exploration

Beyond the urgent need to agree on a package to pay back NGEU, the debate about own resources should focus on whether the EU will be able to build genuine own resources based on common tax policies.

This is a more fundamental debate, raising the question of the nature of the European Union, and the debate between those seeing it as a confederation of sovereign states and those believing in its federal destiny.

For the time being, the Treaties reflect the situation in which tax remains at the core of national sovereignty and consent to tax, one of the fundamental human rights, a pure national exercise. The EU’s unanimity rule on tax-related decisions is the basic translation of this stubborn reality, in which it is unlikely that the European Parliament would be considered as sufficiently legitimate to consent to tax.

The decision-making difficulty resulting from unanimity is increased by the interests of member countries not being aligned. Large EU countries and other high-tax countries have an interest in establishing a common tax base, which would limit tax leakage, for both individuals and companies, even at the cost of limiting their sovereignty.

On the contrary, to attract investment, most of the small members have to compensate for the sizes of their economies, or their peripherical geography, with lower taxes, in particular on mobile factors, including corporate profits or high-income earners. Diverging interests and unanimity are why the EU is in a stalemate situation.

It could be observed that previous EU enlargement to low-tax countries, such as Malta and Cyprus, without changing the decision-making rules, or asking these countries to change their laws before joining the Union, has just made the issue more intractable.

Overall, this means that the prospect of genuine own resources deriving from harmonised taxes remains remote, as unanimity is unlikely to be reached any time soon.

Moving from unanimity to qualified majority voting in tax decisions, which would require Treaty changes, can only reflect agreement on the nature of the institutions. This does not seem feasible, especially at a time of rising populism when national sovereignty is increasingly emphasised.

The current situation, within the EU, reflects a tax anomaly. To avoid leakage, national tax systems provide for tax borders: residents are taxed on their worldwide incomes and countries tax non-residents via withholding taxes on the incomes they derive from those countries.

In short, to avoid leakage, outbound payments (including dividends, interest, royalties and salaries) are subject to withholding taxes, while anti-abuse rules ensure that residents don’t shift profits abroad. With globalisation, the robustness of these rules has been tested.

International efforts driven by the G20 and the OECD since 2008, to introduce a tax regulation of globalisation have aimed to restore these instruments in a coordinated manner, rather than a situation of pure protectionist unilateral tax measures.

The EU offers however a unique environment in which countries have lost their ability to apply taxes at the internal borders (within the internal market) following a set of EU Court of Justice decisions starting in the 1990s, which have found anti-abuse rules to be discriminatory.

As a result, high-tax countries lost their ability to limit the risk of profit shifting within the EU, where there are low-tax countries. Low-tax countries, as part of their ‘tax offer’ to foreign investors, removed their own external borders, when they had such measures.

For instance, they used to offer hybrid instruments and entities allowing companies to book profits generated in Europe in no-tax jurisdictions like Bermuda or Cayman Islands. They also usually offer no withholding taxes and no controlled foreign company regimes, providing tax planners with easy opportunities to shift profits outside the EU at a very low tax cost.

In short, the EU offers the possibility to do business in a high-tax country, shift the profits to an EU low-tax country, without any toll, and then shift the profits to a low- or no-tax country outside the EU, still without any toll.

In parallel with OECD progress on fighting base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS), the European Union has adopted an unprecedented number of tax directives, with various directives on administrative cooperation (which deal with exchange of information between tax authorities13) and two directives on anti-abuse rules.

These EU instruments implement rules adopted at the OECD by the Inclusive Framework. These directives bring more coherence to the system by increasing cooperation between tax authorities, and also by helping members to protect their tax base.

The most recent example is the directive translating into EU law the OECD Pillar 2 agreement establishing a global minimum tax, which EU countries should have implemented by the end of 2023 for entry into force in 2024 (Directive (EU) 2022/2523).

Preceded by global agreements, facilitating a worldwide level-playing field, these EU instruments show that EU members can overcome the constraints of unanimity. The EU has even been able to go beyond OECD efforts with a directive mandating publication of the country-by-country reports of multinationals (the issue was considered as non-tax and therefore was ruled with qualified majority).

Some of this recent progress could facilitate a move towards genuine EU own resources. For instance, the 15 percent global minimum tax could have offered an opportunity to mutualise some resources at the EU level as a genuine own resource.

The minimum tax rules provide for a complex three-tier mechanism to ensure that profits of multinationals, where initially taxed below an effective 15 percent in a jurisdiction, will finally be taxed at 15 percent.

First, the country of residence of the multinational will include any such low-taxed income in its tax base and will collect the additional tax (the Income Inclusion Rule, IIR).

If a country does not exercise that taxing right, countries where the company sells its goods or services will have a right to collect the additional tax (the difference between the effective tax rate in any jurisdiction where the company operates and the 15 percent effective rate), through what is known as an undertaxed profit rule (UTPR).

In addition to the IIR and the UTPR, countries where profits are taxed below 15 percent (either because it is a no-tax country, or because it offers a tax holiday, as can be the case in developing countries) can decide to take the difference themselves through a domestic minimum top-up tax (DMTT).

While the nature of the IIR and the DMTT seems quite national (a country will tax the profit of its own companies abroad), the nature of the UTPR is less domestic. Concretely, if a US or Chinese company (these two countries have not so far moved to implementing the minimum tax rules) operates on the European market with under-taxed profit in a low-tax jurisdiction (say the Cayman Islands or Bermuda where there is presently no corporate income tax for the time being), European countries will be entitled to collect the tax.

Though the collection of the tax will be national, the right to tax, which will depend on allocation rules, seems logically to belong to the internal market and the EU as a whole. It may not be too much of a stretch to compare this with the CBAM, a quasi-tax at the border.

In that sense, it is surprising that the European Commission did not examine this option, and favoured, in its initial proposal, a share of the allocation of taxing rights resulting from the other OECD Pillar (Pillar 1). It is true that the distribution of the global additional annual €150 billion to €190 billion of revenue remains unclear and that, in the long term, this revenue may dry up with tax competition being neutralised.

Still, an opportunity to push for what could be seen as a tax at the border of the internal market, aiming to protect the market from harmful competition, may have been missed.

In theory, one could argue that the DMTT is a way for low-tax countries to put an end to their aggressive tax offers, which allowed excess profit to be allocated to their territory, in a way that is not commensurate to activity deployed there.

The OECD estimates that a significant part of the additional revenue will be captured, at least in the short run, through DMTTs (Hugger et al 2024). This additional revenue could in theory be mutualised, even though, focussing on UTPR, as an external tax border, seems like a more realistic and practical way. It is also consistent with the fundamental structure of tax systems.

More broadly, exploring how other external tax borders of the EU could be restored could be a way to move towards genuine new own resources. For instance, in the area of personal income tax, establishing a common exit tax on EU countries’ residents moving abroad to avoid paying capital gain taxes could serve the purpose of protecting EU countries’ tax bases and developing a new own resource.

This could also be considered in the field of wealth taxation or inheritance duties, even though it must be recognised that the lack of harmonised approaches to these taxes by EU countries does not help define a common external policy.

Fundamentally, however, the idea of establishing external tax borders, to limit the risk of the delocalisation of the tax base (through exit taxes on unrealised capital gains for instance), could be further explored and may be a way to move forward the tax conversation in Europe.

Rather than harmonising taxes, which proves difficult, focusing on protecting the revenues of EU members by common borders may unleash some potential.

5 Conclusion

The European Commission’s June 2023 adjusted proposal for own resources was motivated by the need to ensure a swift move towards adopting additional own resources to fund NGEU. The agreement to start debt financing the EU included an agreement to adopt new own resources.

Failure to move forward would jeopardise the ability of the EU to keep funding its existing projects, especially at a time when interest rate increases will make the repayment of both capital and interest heavier.

Time is running out, and the Commission proposed an adjusted mechanism that is pragmatic and rebalances the burden to make it more acceptable to Eastern European countries. It is a good move, even though no conversation has yet seriously taken place in the Council.

More importantly, the real debate on how to establish genuine own resources still needs to take place. A move to ETS and CBAM revenue to be mutualised is good and would give more weight to real own resources, aligned with EU policy objectives.

More needs to be done and recent international tax progress are a unique opportunity for the EU to explore how it could bring more consistency to tax systems in the EU while developing own resources.

Endnotes

1. The VAT and the GNI resources, based on statistical aggregates, are paid by members, which consider them to be national contributions, rather than resources owned by the EU.

2. In December 2020, the European Parliament, the Council and the Commission adopted an agreement on budgetary discipline, cooperation on budgetary matters, sound financial management and new own resources; see https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=uriserv%3AOJ.LI.2020.433.01.0028.01.ENG&toc=OJ%3AL%3A2020%3A433I%3ATOC.

3. This was brought forward: a decision on a second basket of own resources was initially envisaged for June 2024.

4. See European Council notice of 1 February 2024, ‘Special European Council, 1 February 2024’.

5. This own resource is proportional to the quantity of plastic packaging waste that is not recycled. EU countries contribute €0.80 per kilogramme of plastic packaging waste that is generated in their territory and not recycled.

6. See European Commission press release of 20 June 2023, ‘EU budget: Commission proposes to reinforce long-term EU budget to face most urgent challenges’.

7. See https://www.oecd.org/tax/beps/about/.

8. See for example Reuters, ‘“Enough excuses!” France’s Le Maire grows impatient over GAFA tax’, 18 October 2018. GAFA refers to Google, Amazon, Facebook and Apple.

9. The Business in Europe: Framework for Income Taxation (BEFIT) proposal, which aims to reboot negotiations on a common EU approach to taxation of corporate profits. See European Commission press release of 12 September 2023, ‘Taxation: new proposals to simplify tax rules and reduce compliance costs for cross-border businesses’.

10. See the European Parliament resolution of 10 May 2023, ‘Own resources: A new start for EU finances. A new start for Europe’.

11. The examined additional seven own resources were: (i) corporate tax BEFIT (no fast mobilisation planned), (ii) a financial transaction tax (same), (iii) an EU fair border mechanism aimed at fighting social dumping (modestly meeting the criteria), (iv) a tax on crypto-currencies (same), (v) a statistical resource based on gender pay gap (no fast mobilisation), (vi) a statistical resource on food waste, and (vii) a statistical resource based on e-waste, the latter two with a good prospect of fast mobilisation but only adequate simplicity and revenue potential.

12. See https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/45109/210720-euco-final-conclusions-en.pdf.

References

Claeys, G, C McCaffrey and L Welslau (2023a) ‘The rising cost of European Union borrowing and what to do about it’, Policy Brief 12/2023, Bruegel.

Claeys, G, C McCaffrey and L Welslau (2023b) ‘An estimate of the European Union’s long-term borrowing cost bill’ Briefing for the European Parliament BUDG Committee.

Council (2020) ‘Council Decision 2020/2053 of 14 December 2020 on the system of own resources of the European Union’, Council of the EU.

European Commission (2021) ‘The evolving nature of the EU budget’, EU Budget Policy Brief 1.

European Commission (2023a) ‘An adjusted package for the next generation of own resources’, COM(2023) 330 final.

European Commission (2023b) ‘Staff Working Document accompanying the amended proposal for a Council Decision on the system of own resources of the European Union’, SWD(2023) 331 final.

Fuest, C and J Pisani-Ferry (2020) ‘Financing the European Union: new context, new responses’, Policy Contribution 16/2020, Bruegel.

Hugger, F, AC González Cabral, M Bucci, M Gesualdo and P O’Reilly (2024) ‘The Global Minimum Tax and the taxation of MNE profit’, OECD Taxation Working Papers 68, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

This article is based on Bruegel Policy Brief Issue no06/24 | March 2024.