A framework for geoeconomics

Christopher Clayton does research in finance, international macro-finance, and macroeconomics, Matteo Maggiori is the Moghadam Family Professor of Finance in the Graduate School of Business at Stanford University, and Jesse Schreger is the Class of 1967 Associate Professor at Columbia University

Governments use their countries’ economic strength from existing financial and trade relationships to achieve geopolitical and economic goals, a practice often referred to as ‘geoeconomics’. Great power competition between the US and China has made geoeconomics part of daily news and an active policy choice in democracies and autocracies alike.

Recent examples include China’s Belt and Road Initiative, the US attempting to restrict the use of Huawei’s 5G technology in Western countries, and the US using the dollar-based financial system as part of a range of trade and financial sanctions against Russia.

In two landmark contributions, Hirschman (1945, 1958) relates the structure of international trade to international power dynamics and sets up forward and backward linkages in input-output structures as a foundation for structural economic development.

In a new paper (Clayton et al 2024), we introduce a framework, inspired by this work, that uses an input-output network model of the world economy to explain how geoeconomic power arises from the ability to consolidate threats across multiple economic relationships (eg. finance and technology jointly) to pressure a target entity.

In our model, a hegemon like the US exerts its power on firms and governments in its economic network by asking them to take costly actions that manipulate the world equilibrium in the hegemon’s favour.

Geoeconomic power arises from the ability to jointly exercise threats from separate economic activities, for example, threatening to cut off a deviating entity from both financial services and critical manufacturing inputs.

We characterise the optimal strategy of a hegemon and show that a hegemon asks targeted firms to take costly actions such as imposing or accepting mark-ups on goods or higher rates on lending, but also import restrictions and tariffs.

The network nature of the world economy makes controlling certain strategic sectors more valuable for the hegemon. Strategic sectors increase the hegemon’s power over other sectors or its influence over the world economy due to network amplifications.

We apply our framework to two prominent examples: (1) national security externalities in the setting of US-China competition; and (2) China’s Belt and Road Initiative as a sovereign lending programme.

Collective power over multiple entities gives rise to the hegemon’s macro-power – its ability to reshape the world’s equilibrium in its favour

Hegemonic threats to friends and enemies

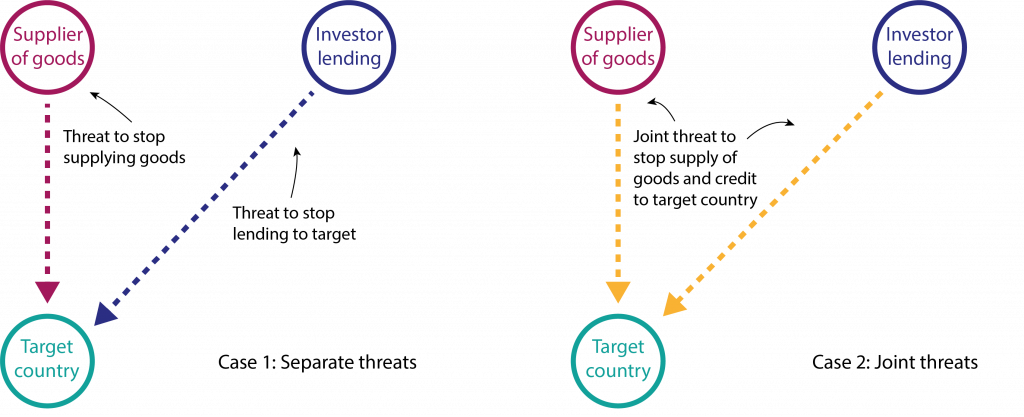

Hegemons build power by threatening to retaliate against a deviating entity across multiple economic relationships. For example, a target country might be importing both intermediate goods and foreign capital (Figure 1a). If these inputs are controlled separately, there is some value to individual threats.

Generally, however, threats to withdraw both inputs at once (Figure 1b) are more powerful in the sense of inducing greater losses for the target country if exercised.

Figure 1. Networks and joint threats

Many threats are either not feasible or not valuable. A threat is not feasible if the hegemon does not control the input. Not valuable means that the target country can easily find a substitute for the input that is withdrawn. For example, Russian threats to withdraw natural gas supplies are less powerful if alternative suppliers can be found.

A hegemon uses these threats to exert power over firms and governments in its network and ask them to take costly actions. These actions can take the form of monetary transfers, mark-ups on trade prices, and surcharges on loans, but also restrictions on import-export (tariffs and caps) and political concessions.

We provide a theory-based notion of friends and enemies of the hegemon (see also Kleinman et al. 2020). Our notion of friendliness is not based solely on nationality or political affinity, but on how an activity impacts the hegemon’s welfare either directly or indirectly via its impact on others.

For example, the US might consider a sector producing semiconductor technology in the Netherlands unfriendly in as much as its output is indirectly increasing production of unfriendly technology by China.

Which sectors are strategic?

The designation of an activity as ‘strategic in the national interest’ is often abused in economic policy. It can mask protectionist or nationalistic aims of government policy. The abuse is possible due to the lack of a clear definition and policy framework against which to assess a candidate policy.

In our framework there are two notions of power: micro-power and macro-power. Sectors are strategic if they increase these powers. A sector is strategic in the micro-power sense if it increases the hegemon’s ability to make valuable threats on other entities.

We refer to this as micro-power since it takes as given all aggregate quantities and prices. Strategic sectors tend to supply inputs to other sectors that are widely used and are not easily substitutable. Some sectors have physical properties of this kind, for example rare earths.

Other sectors exhibit these properties because of increasing returns to scale and natural monopolies. An example is the dollar-based payment and settlement system that the US often uses in geoeconomic threats. The dollar system is so ubiquitous that on the margin countries that are excluded have only poor alternatives.

Collective power over multiple entities gives rise to the hegemon’s macro-power – its ability to reshape the world’s equilibrium in its favour. Some sectors have high indirect influence on world outcomes by affecting prices or quantities produced by other sectors.

These sectors are strategic because control over these sectors allows a hegemon to influence indirectly a large part of the world economy that it does not directly control. Research and technology, especially at the cutting edge or for military use, are sectors of this kind.

Understanding the US restrictions on Huawei

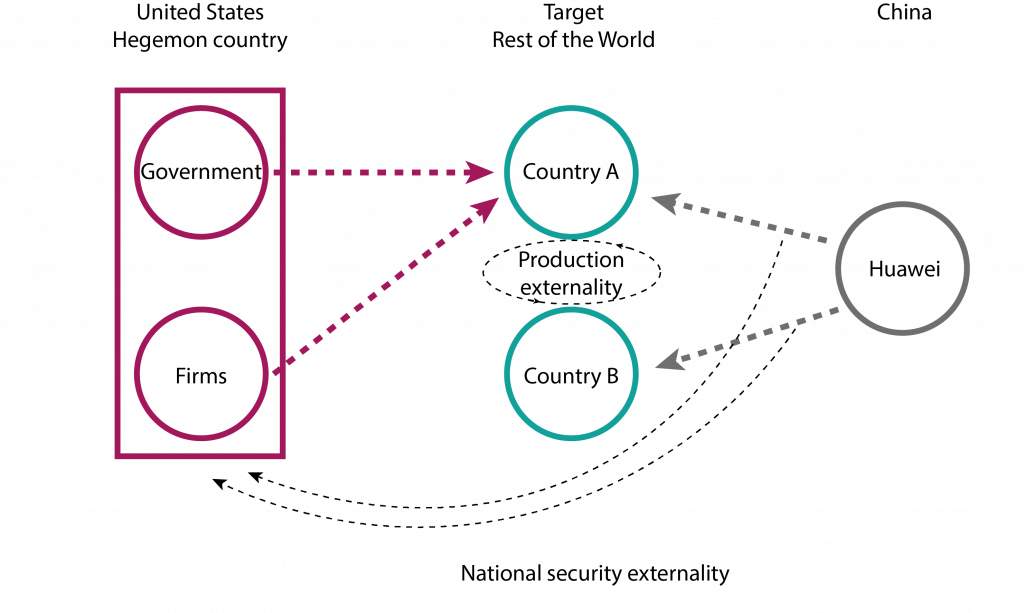

We consider the US hegemon demanding that countries in Europe stop using a technology input from China that is a national security concern for the US.

As illustrated in Figure 2, the hegemon US can pressure firms and governments in third party countries to curb their imports of Chinese company Huawei’s 5G telecommunication infrastructure even though there are benefits to these users from using such technology.

Figure 2. US national security and 5G infrastructure from China

This application highlights the power of endogenous amplification through the production network. We assume that this technology has a strategic complementarity: each user finds the technology more productive the more other users are also using the same technology. These complementarities are typical of information technology but are also present in financial technologies like payment systems.

The US wields its macro-power by demanding entities in its network to curb the use of this technology. As targeted sectors use less of China’s technology, the technology becomes less attractive also to other sectors that the US cannot directly pressure, increasing the overall impact of US demands.

Understanding the Belt and Road Initiative

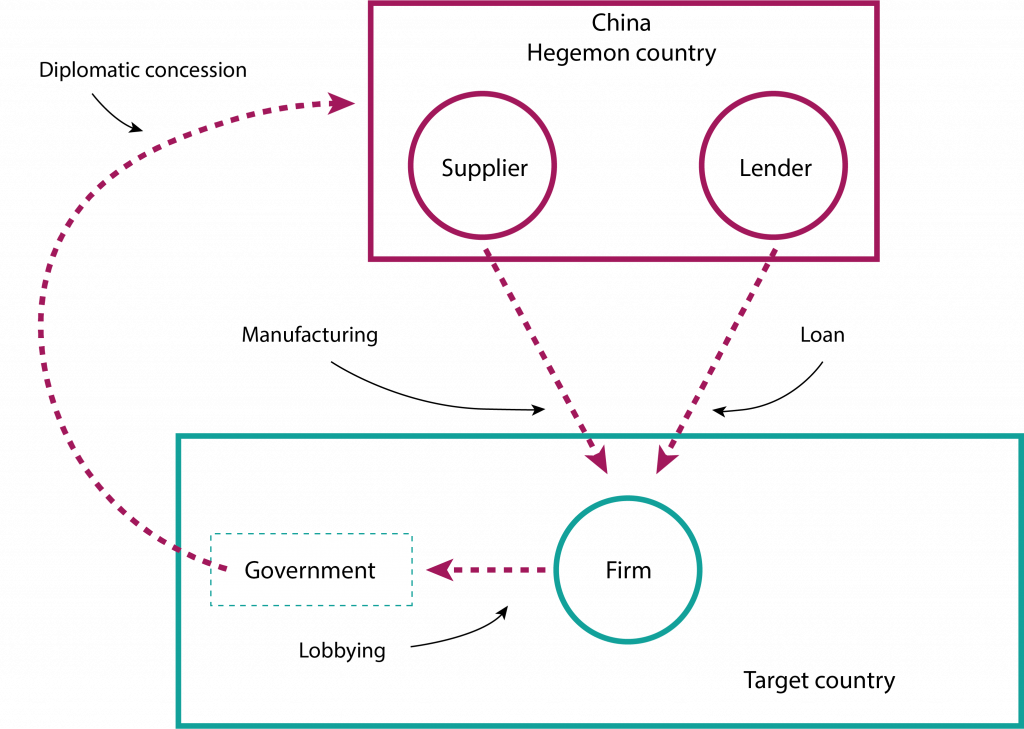

China’s flagship Belt and Road Initiative provides countries involved package deals of lending, infrastructure projects, and manufacturing inputs. China often extracts political concessions and or better access for its firms to new markets.

We model how China can combine lending and manufacturing exports to extract political concessions (Figure 3). We consider a target country with low legal enforcement, eg. an emerging or frontier market. In the absence of China’s geoeconomic power, the country has limited willingness to repay the debt.

However, China can threaten to jointly stop the financing and reduce the supply of manufacturing goods if the target country does not repay the debt or attempts to expropriate the goods. This joint threat is very powerful, and it expands economic activity that can be carried out in the targeted country.

China extracts some of the value created in these economic relationships in the form of political concessions, for example, closer alignment over the recognition of Taiwan.

Figure 3. China’s Belt and Road Initiative

References

Clayton, C, M Maggiori and J Schreger (2023), “A framework for geoeconomics”, NBER Working Paper No. w31852.

Hirschman, AO (1945), National power and the structure of foreign trade, Vol. 105, University of California Press.

Hirschman, AO (1958), The Strategy of Economic Development, New Haven: Yale University Press.

Kleinman, B, E Liu and SJ Redding (2020), “International friends and enemies”, NBER Working Paper No. w27587.

This article was originally published on VoxEU.org.