The rocky road to EU accession

Armin Steinbach is a Non-Resident Fellow at Bruegel and Jean Monnet Professor for EU law and economics at HEC Paris

Executive summary

The Western Balkan countries and the countries of the Eastern Partnership are moving towards European Union accession at different speeds. We explore whether and how the variable speed towards EU accession can be traced to different legal regimes governing European integration: Stabilisation and Association Agreements (SAA) for the Western Balkan countries, and Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreements (DCFTA) for the countries of the Eastern Partnership (EaP).

We find that DCFTAs apply more lenient conditionality to intra-regional cooperation. They subject non-tariff barriers to a more explicit regime than the Western Balkan SAAs. The DCFTAs also off er a more rigid and comprehensive approach to the approximation of laws than the SAAs, and the DCFTAs are more inclusive with regard to the role of civil society.

However, there is no indication that the differences in legal governance have translated into stronger economic performance in the EaP countries or greater integration with the EU, compared to the Western Balkans.

The Western Balkan countries remain significantly more integrated than the EaP countries with the EU in trade terms, while convergence with the EU has been stagnating both for the Western Balkan and the EaP countries. Economic shortcomings in the Western Balkan still need to be addressed.

Conditionality attached to both integration into the EU single market and EU funding should be nuanced; the eradication of non-tariff barriers should be prioritised both inter-regionally and intra-regionally between Western Balkan countries; the need for stronger EU investment in the region is reinforced by geopolitical concerns about Chinese investments coming without EU-type conditionality attached; and governance should give a stronger role to civil society.

In order to address the shortcomings in SAAs, a pragmatic solution is to use the existing governance framework under the SAAs.

1 Introduction

Until the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the European Union pursued a two-track approach to its south-eastern and eastern European neighbours. The EU accession prospects of the Western Balkan (WB) states (Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, North Macedonia, Montenegro, Kosovo and Serbia) were more promising than those of their eastern counterparts – in particular Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine – which were associated with the EU through its Eastern Partnership (EaP).

Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine declared they wanted to join the EU in the mid-2000s, but for a long time the EU preferred alternative models: first the European Neighbourhood Policy (in 2004) and then the EaP (in 2009). But though the EU pursued an integration model in relation to the EaP that did not aim at EU accession, Russia’s war against Ukraine triggered a change to this two-track approach.

Suddenly, the process, at least with Ukraine, Geogia and Moldova (which are the reference point of comparison with the WB in this paper), turned into an accession process, ushering in the initiation of accession negotiations with Ukraine and Moldova in December 2023.

The three eastern European states had practically no waiting time before being accepted as candidate countries right after application (Box 1). This contrasts with the Western Balkans, with either, as for North Macedonia, a decade of waiting for the opening of accession negotiations because of resistance from some EU member states or, as for Serbia, a decade of dragging negotiations because of democratic backsliding.

As the progress report in Box 1 shows, given that WB applications to accede to the EU date back as far as 2004, the accession process has advanced much more slowly than for the EaP countries that applied only in 2022.

Yet, new impetus has spilled over to the WB, as the EU opened accession talks with Albania and North Macedonia in July 2023 and with Bosnia and Herzegovina in March 2024, while Kosovo officially submitted its membership application in 2022.

The new ‘reversed order’ of accession, with Ukraine seemingly outpacing the WB since 2022, adds to a dissatisfaction with the WB accession process that has long been growing. Among WB countries, the dominant perception was that the EU promise of WB membership was not credible, while the EU felt persistently concerned about the lack of “genuine domestic reforms” and remaining political rifts in the region (Dabrowski, 2022).

Ukraine’s rapid move towards accession raises the question – notwithstanding the political accelerator for Ukrainian accession arising from the Russian assault – whether there are lessons to be learned from the new ‘front runners’1.

With the relationship between the EU and Ukraine, Georgia, and Moldova now governed by a different set of agreements and governance, this paper explores possible differences between the relationships the two blocs have with the EU.

It has been argued – but not analysed in depth – that the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreements (DCFTA) led to Ukraine, Georgia and Moldova being better integrated with the EU in terms of their access to its markets, than the Stabilisation and Association Agreements (SAAs) did for WB countries (Blockmans, 2018). The DCFTAs form part of the countries’ Association Agreements with the EU and supplement and deepen their integration into the EU internal market.

Our analysis explores more deeply the comparison between the two groups of agreements. Clearly, we consider the pre-war situation and as such exclude that war-related geopolitical factors changed the accession pace of EaP countries, and of Ukraine in particular.

Specifically, we seek to better understand the differences in regimes and access to the EU internal market. First, we systematically assess and compare the substantive, procedural and institutional differences between the eastern European AA/DCFTAs and the WB SAAs with respect to their potential in offering access to the EU internal market.

Despite large similarities between the agreements, we find considerable differences in legal governance related to conditionality, non-tariff barriers of trade, trade in services, foreign direct investment (FDI) and the approximation of laws. We extend the comparative analysis to shortcomings in the governance and implementation process of the relevant SAAs and working plans.

Second, in view of the differences, we explore the extent to which they may have had an impact on economic performance in terms of convergence with the EU, trade in goods and services, non-tariff barriers, FDI and what measures should be implemented to overcome the existing shortcomings.

These could be implemented either by modifying the WB SAAs or through modifications to the level of technical implementation. We caution against claiming a causal effect in terms of the differences in legal governance leading to Ukraine to obtain the status of accession negotiations so rapidly (geopolitical reasons are likely to trump the modest performance of Ukraine, for example).

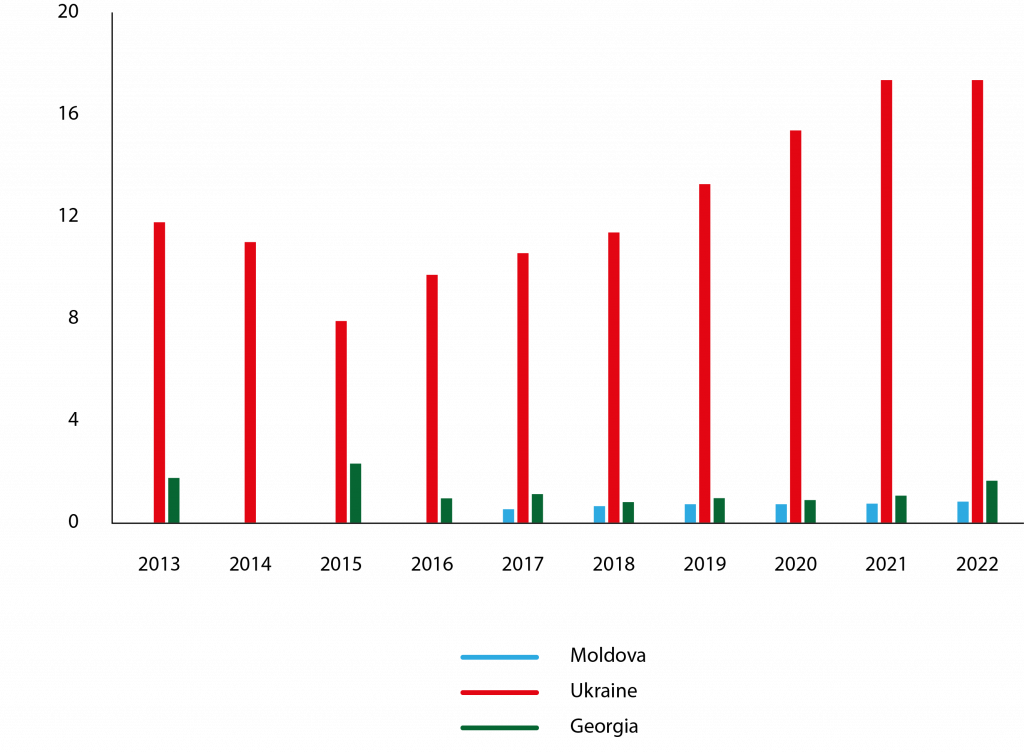

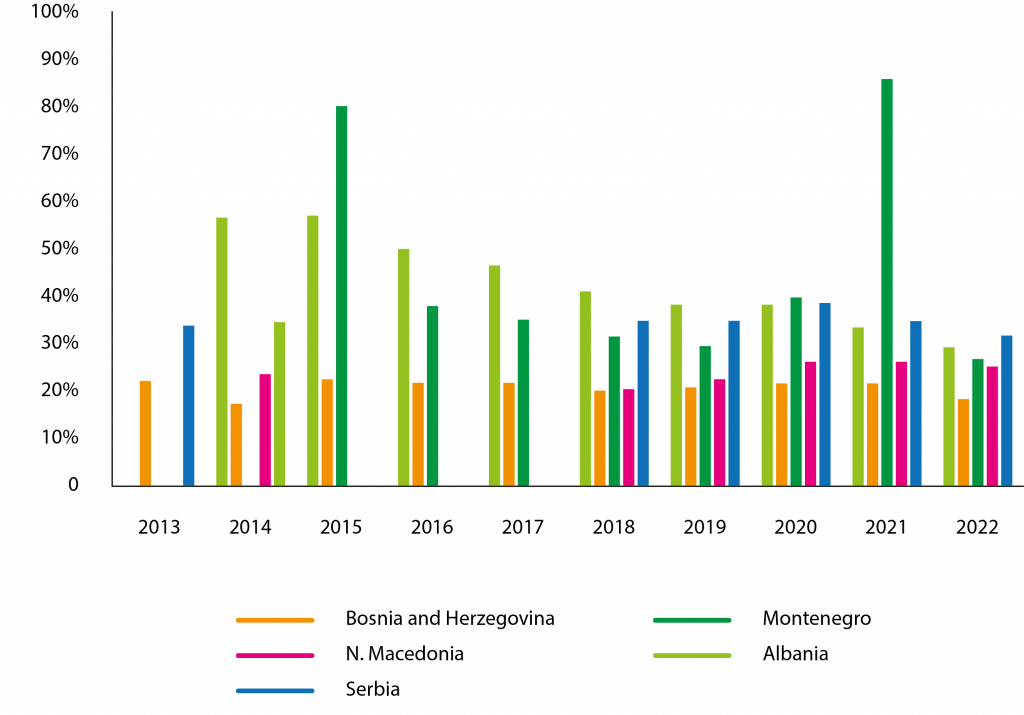

Our analysis comes at a critical time. Political sentiment in some WB countries, particularly Serbia and North Macedonia, blames the EU for slow accession, while democratic backsliding and authoritarian regimes in the WB is leading to China and Russia, as underpinned by an influx of Chinese FDI (Figure 7), to be seen as alternatives to moving closer to the EU, with the EU portrayed as just one among the external players in the region (Vulović, 2023).

The new Growth Plan (European Commission, 2023a) and the draft Reform and Growth Facility for the Western Balkans (European Commission, 2023b) seek to revive WB integration. While additional funding for the region will be made available, the new proposal brings a demanding degree of conditionality, increasing the pressure for domestic reforms (in line with the EU Copenhagen, or accession, criteria), and setting additional intra-regional integration as cumbersome preconditions, both for internal market access and funding eligibility.

Yet, the current negotiations of a roadmap for Ukraine’s accession to the EU may offer a new momentum for the WB states to integrate further into the EU single market, by underlining the mutual benefits. The new geopolitical reality enhances the significance of the EU’s enlargement policy, but for it to materialise, it requires modification of the current regime governing market access, financial investment and governance.

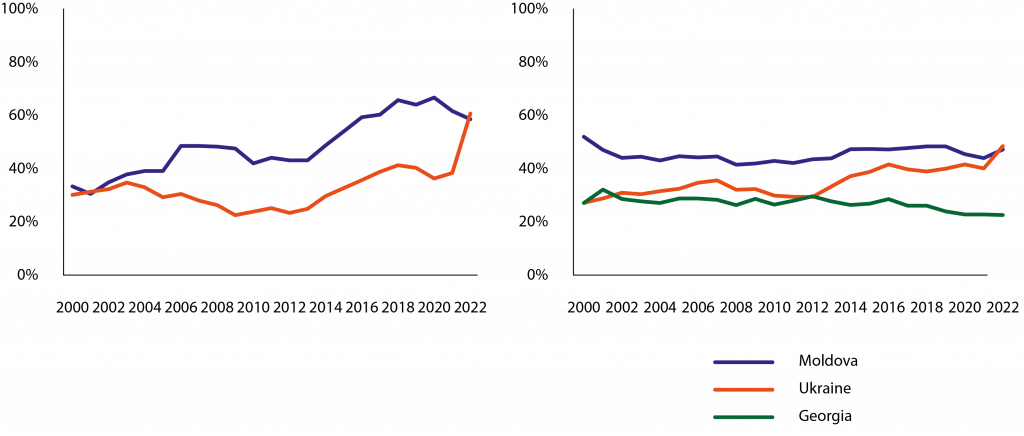

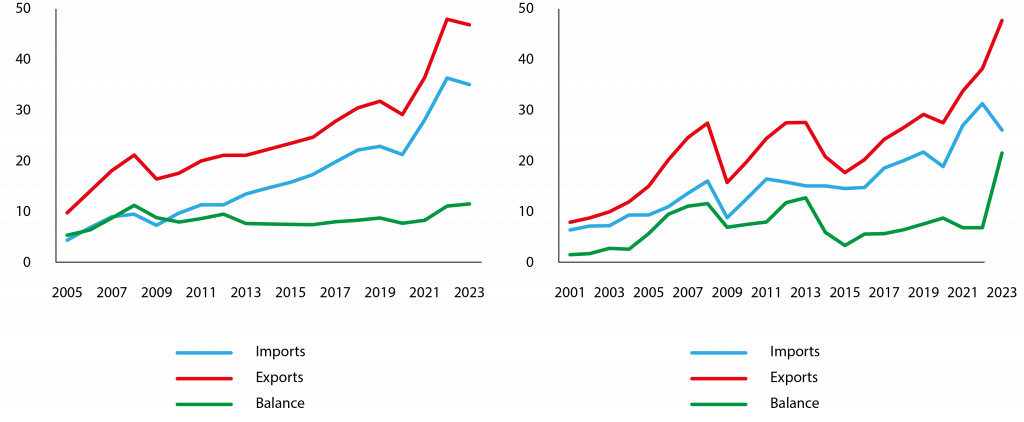

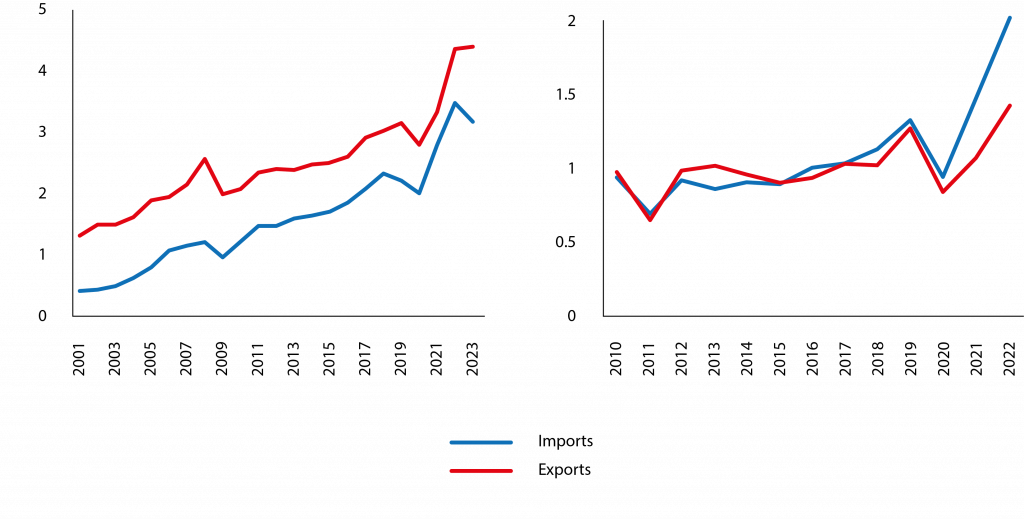

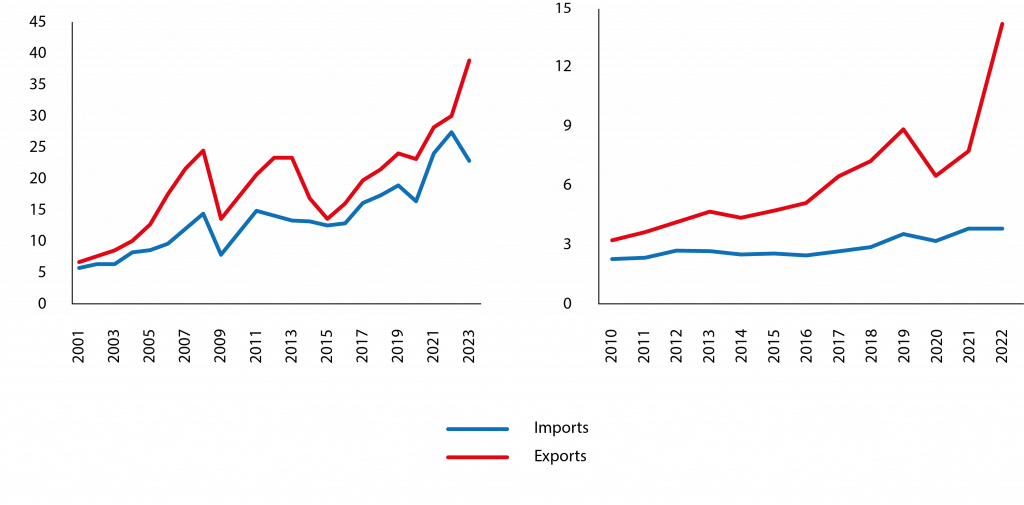

We focus on access to the single market both from the perspective of substantive market access and governance of the implementation. The EU is the key trading partner of the Western Balkans, with WB goods exports to, and imports from, the EU in 2022 amounting to €37 billion and €48 billion respectively (equating to simple averages of approximately 59 percent and 49 percent of their respective trade totals; Figure 1). Services trade between the two is also significant, with exports to and imports from the EU amounting to approximately €8.5 billion and €7.5 billion respectively for the same year (Figure 6)2.

However, the WB share of exports to and imports from the EU27 has been constant in average over the last twenty years. Since the sequential entry into force of SAAs since 2004 there has not been a significant increase in trade integration with the EU. In turn, the share of the EU as an export destination for EaP goods has on average increased (Figure 1b).

Figure 1a. The EU as an export destination (left) and import source (right) for WB goods (% of total exports and imports respectively)

Figure 1b. The EU as an export destination (left) and import source (right) for EaP goods (% of total exports and imports respectively)

Source: Bruegel based on IMF Direction of Trade Statistics.

At the same time, the rate of convergence of the Western Balkans countries was described in the new Growth Plan as “not satisfactory” and “holding back their progress on the EU track” (European Commission, 2023, p.1).

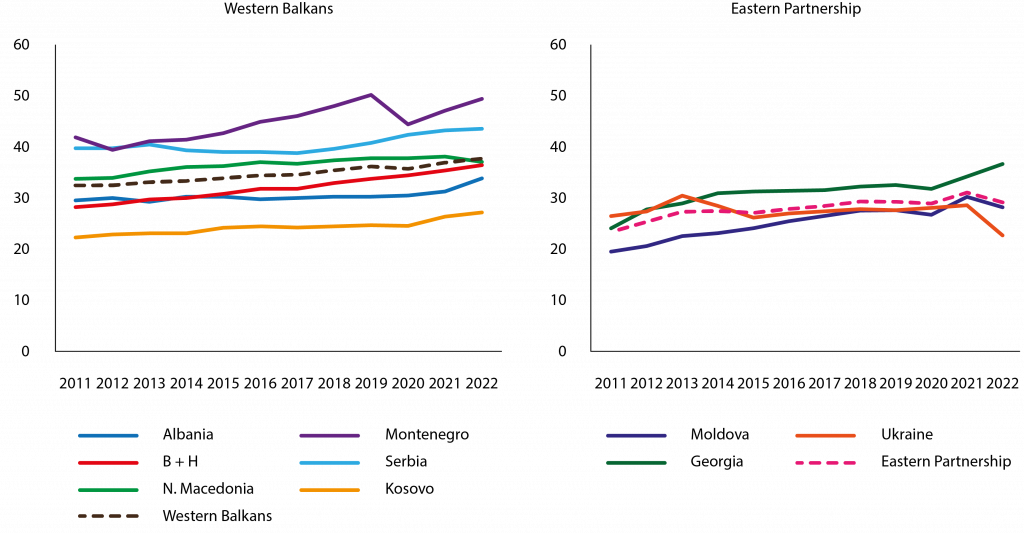

As illustrated in Figure 2, both regions have struggled with GDP per capita convergence to the EU27 average, recording moderate gains between 2011 and 2021. WB countries had higher initial GDP per capita level than the EaP countries (by approximately 10 percentage points of average EU27 GDP) but caught up less quickly up to 2021. In 2022, Ukraine and Moldova recorded reversals of their previous growth trends, because of Russian aggression against Ukraine.

Figure 2a. GDP per capita in PPP (percent, EU27 = 100)

Figure 2b. GDP per capita in PPP (percent, 10 central and eastern European countries = 100)

Note: The Western Balkans and Eastern Partnerships dashed lines are simple averages. For an insight into convergence in the regions in general, a weighted approach to account for population may be more appropriate. However, the relevant metric for accession is the convergence of the countries in question, not the regions as a whole. These averages are only included for ease of comparison.

Source: Bruegel based on World Bank World Development Indicators.

The stagnating share of the EU27 in trade with the WB, and the moderate pace of convergence, provide the economic motivation for our analysis and for exploration of a possible connection to the legal regime set out in the SAAs.

Based on our comparative legal and institutional analysis, we identify a number of differences between the agreements the EU concluded with the eastern European countries and the WB. Yet while differences in the legal governance of DCFTAs and SAAs would suggest WB economic underperformance compared to the EaP, because of a legal framework limiting WB integration into EU internal market in comparative perspective with the DCFTAs, this is not supported by the available economic evidence.

While these differences are significant deficiencies and should be addressed, we hasten to say that there is no compelling evidence that remaining shortcomings can causally been traced to the different legal treatments.

In any case, taking the DCFTAs as an example, the remaining constraints in the SAAs and in the new Growth Plan should be lifted to untap further potential for WB convergence with the EU internal market.

The importance of EU single market membership to West Balkan economic prospects cannot be overstated

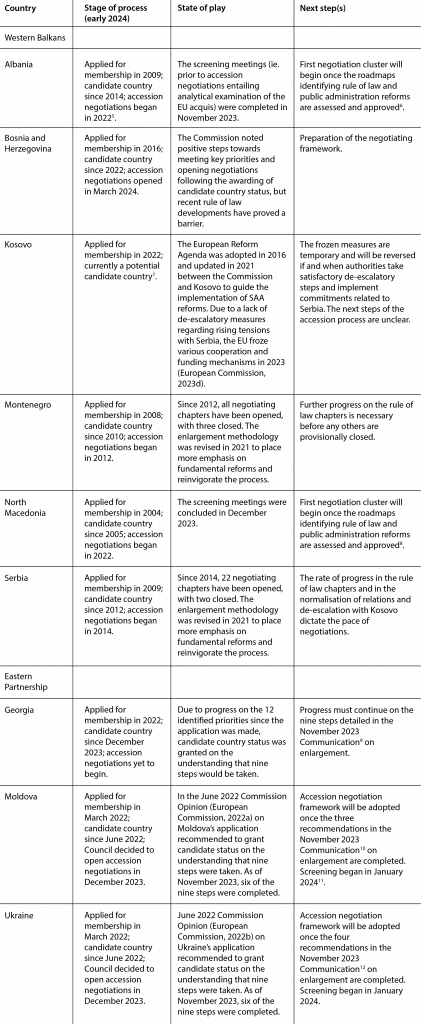

Box 1. The nature and state of play of the Accession talks3

The EU accession process involves five main steps4. First, a country must apply to the Council of the EU to become a member. Article 49 of the Treaty on the European Union (TEU) stipulates that any European country that respects and commits to the values of the EU as expressed in Article 2 TEU can apply, and this is the stage that Kosovo is currently at.

The second step is a positive assessment of the Commission recommending the granting the candidate status. Third, candidate status is approved based on a unanimous decision of the European Council, which is what happened for Georgia for instance in December 2023. However, this does not necessarily mean that formal negotiations have been opened.

The fourth step is the accession negotiations, which begin with a detailed examination (screening) carried out by the Commission, together with the candidate country, of each policy field (chapter), to determine how well the country is prepared. This initial screening exercise of the EU’s acquis serves to identify levels of preparedness in each policy field (which Albania and North Macedonia completed in 2023).

If completed satisfactorily, negotiations ensue focusing on six different thematic clusters, each consisting of various chapters; these negotiations take place at intergovernmental conferences (Montenegro, for instance, has opened negotiations on all chapters and closed three).

Fifth and finally, the process concludes when all chapters have been closed and an accession treaty is approved unanimously by the European Council and receives the consent of the European Parliament. Each EU country must also ratify the treaty according to its constitutional procedures (Dabrowski, 2014).

2 Comparing DCFTAs and the Western Balkan SAAs in terms of EU market integration

This section highlights differences between the legal regimes governing market access for the eastern European countries of Ukraine, Moldova and Georgia (on basis of DCFTAs) and the applicable framework under the Western Balkan SAAs. Differences are explored in relation to five benchmarks: conditionality, non-tariff barriers to trade, trade in services, movement of capital and the approximation of laws.

Annex I provides a comprehensive comparative assessment of the relevant agreements and the applicable rules, while this section discusses some of the marked differences. What facilitates the comparison (while highlighting the stark differences between the regimes) is a large degree of homogeneity in agreements within each group – within DCFTAs and Western Balkan SAAs. For the purpose of making comparisons, the Serbia SAA13 will be the reference point for the WB SAAs, while the Ukraine AA/DCFTA14 is referred to to exemplify the agreements the EU concluded with the eastern European partners.

2.1 Regional integration as conditionality

One core distinguishing feature between the DCFTA and the WB SAAs is the degree of conditionality attached to intra-regional integration as a precondition for further access to the EU internal market.

Most recently, this emphasis has been reiterated in the draft New Growth Plan, which, as an extension of the WB SAAs, makes single market access conditional not only on political and economic domestic structural reforms, but on the progress made in intra-regional market integration.

The Serbia SAA emphasises regional cooperation by requiring the WB country to “enhance its cooperation” and to “implement fully the CEFTA” (Article 14 Serbia SAA) – the Central European Free Trade Agreement governing trade relations between the WB states.

The Serbia SAA further requires the conclusion of additional bilateral conventions with WB countries that foster political dialogue, establish free trade, cooperation in justice affairs and provide free market access more globally (Article 15 Serbia SAA).

This conditionality has been constantly upheld in the EU’s policy on the WBs, with the most recent draft Growth Plan tying access to EU internal market benefits and the release of funds under the draft Reform and Growth Facility (the financial assistance vehicle of the plan) (European Commission, 2023b) to a wide set of reforms.

This extends not only to traditional conditionality securing the Copenhagen criteria, including democracy, rule of law and human rights (which apply to WB and EaP countries alike). In the case of WB, the political conditionality also extends to requiring Serbia and Kosovo to normalise their relations and comply with the relevant agreements governing reconciliation, and to negotiate the Comprehensive Agreement on normalisation of relations (European Commission, 2023b, Article 5).

Importantly and in addition, the EU requests economic intra-regional integration as precondition and conditionality attached to access to the EU single market. For example, the Commission envisages making access to EU financial support through its draft Reform and Growth Facility (European Commission, 2023b) conditional ex ante on the implementation of the Common Regional Market Action Plan.

This Plan is the outcome of the Common Regional Market Initiative of the WB countries, which builds on the CEFTA framework (and thus connects to the conditionality embedded in the SAA). The Plan requires, inter alia, the development of a regional digital market, which requires investment in broadband internet access, 5G and digital services.

The Plan also foresees expansion of green lanes at the border to cut waiting times. Hence, the extended conditionality regime allows the EU to make internal market access and access to funding conditional on WB ex-ante investment in these areas.

This conditionality contrasts with the absence of mandatory regional cooperation under the DCFTAs. The agreements are silent on this type of intra-regional conditionality. Specifically, the Ukraine-DCFTA provides for “regional stability”, stipulating a vague obligation for Ukraine, Moldova and Georgia to “intensify their joint efforts to promote stability, security and democratic development in their common neighbourhood” (Article 9 DCFTA Ukraine).

The main conditionality in the Ukraine-DCFTA is the approximation of the relevant EU law by Ukraine along with the Copenhagen criteria, which must be respected by all EU aspirants. However, the DCFTAs lack the intra-regional layer of conditionality that the EU, in relation to the WB, has increasingly insisted on.

Not only are the DCFTAs lenient on regional integration as a requirement, the question is also whether the EU’s persistent insistence on regional economic cooperation is an adequate requirement. Intra-regional conditionality is plausible if it seeks to alleviate political rifts between Serbia and Kosovo, and societal tension and political blockages in decision-making (European Commission, 2023a; Ghodsi et al 2022). But the economic intra-regional conditionality referred to above appears much more ambivalent.

On one side, creating a common regional market for goods, services and labour within the Western Balkans offers opportunities for increased trade – according to one estimate15, regional economic integration in the Western Balkans could generate up to 2.5 percent of GDP growth, should the level of integration reach the level of that of the European Free Trade Association (EFTA), while it could even generate up to 7 percent should it reach the EU’s level of integration.

The most ambitious initiative negotiated in this regard is the creation of the Common Regional Market16 as an outcome of the Berlin Process, launched in 202017. It foresees WB intra-regional freedoms of goods, services, capital and people, including aspects relating to digital, investment, innovation and industry policy.

On the other side, barriers to intra-regional economic integration lie in the lacking physical infrastructure and persistent inequality in the WB. In particular, lack of public investment in roads, digital infrastructure, railways and energy have been identified as limiting factors (Ghodsi et al 2022).

The Commission itself noted in its November 2023 Communication on enlargement that “there is a strong need to upgrade infrastructure; investments should be… consistent with the priorities agreed with the EU” (European Commission, 2023c, p.11).

Panel B of Figure 3 highlights the limited progress achieved on improving the trade-related intra-regional infrastructure and in closing the gap with the EU, using the broader logistics performance index18 (Figure 3, Panel A), similarly showing low levels of convergence.

Even the central and eastern European EU members (a more adequate group for comparison with WB countries) seem to have been more successful in improving trade-related infrastructure by reducing the gap with other EU members. However, convergence has not been better across the same indicators for the EaP countries (see Annex 4).

Figure 3. Logistics and trade-related infrastructure

Note: Data is available for 2007, 2010, 2012, 2014, 2016, 2018 and 2023. Data for Serbia, Montenegro and Georgia unavailable for 2007. Data for Albania is unavailable for 2014. Data for Kosovo unavailable throughout. WBs is a simple average of the relevant countries. CEE 10 and Rest of EU refer to the simple averages of the central and eastern European countries that joined the EU in the 2000s19 and the other 17 EU countries, respectively. See Annex 4 for the same exercise for EAP countries.

Source: Bruegel based on World Bank Logistics Performance Index.

The connection to conditionality is that with limited public investment in infrastructure identified as one persistent barrier to regional integration in the WB20, the EU should not implement ex-ante conditionality on WB public investments in digital infrastructure or crossborder trade facilities, as set out in the Common Regional Market Action Plan (eg. lanes at borders or customs procedures).

The EU should fund these ‘win-win’ investments, which are beneficial to the WB and the EU alike, rather than blocking EU internal market access because of the lack of these investments. This concerns in particular crossborder infrastructure and networks that are often underfinanced because of a mismatch between costs and benefits and that are, under EU internal market standards, typically eligible for funding. WB infrastructure should be prioritised accordingly. Conditionality attached to these kinds of projects is not a sensible approach.

In fact, intra-regional crossborder transport infrastructure has significant positive spillovers, such as the potential to reduce income disparities across the EU and its neighbouring regions.

In this regard, it is positive that the draft Growth Plan implies revising the trans-European transport framework (TEN-T), in order to include a new corridor crossing the Western Balkan region (Western-East Mediterranean corridor), and the EU’s recent Economic and Investment Plan for the Western Balkans offers financing of rail transport21.

However, conditionality of the new Growth Plan should be relaxed for these infrastructure projects more generally and the involvement of European Investment Bank and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development funding in the investment should be further facilitated (Ghodsi et al 2022).

Finally, conditionality should also be rethought in light of geopolitical rivalry. EU conditionality contrasts with Chinese investment in the region without strings attached, which makes Chinese FDI more attractive.

Again, the legal comparison of WB SAAs with the DCFTAs shows that the latter offer a more explicit acknowledgement of internal market integration. The Ukraine AA is explicit about its objective of bringing Ukraine into the EU internal market (Article I (d) of the Ukraine-DCFTA), while such an explicit recognition of this objective is absent from the Serbia SAA, in which language is limited to “gradually develop a free trade area between the Community and Serbia” (Article 1 (f) Serbia SAA).

While more assertive language in the agreements does not guarantee more favourable economic outcomes, specifying the objective in the agreement can bind the institutions under the SAA to work towards that goal.

2.2 Trade in goods and non-tariff barriers

The EU-Ukraine association agreement has been praised by European Commission officials as “the most ambitious Agreement that the EU has ever developed with any partner”22.

Indeed, by integrating the DCFTA into the Association Agreement, the integration of Ukraine, Georgia and Moldova into the EU has been propelled through wide-reaching market access and regulatory approximation, ushering in increased trade with the EU.

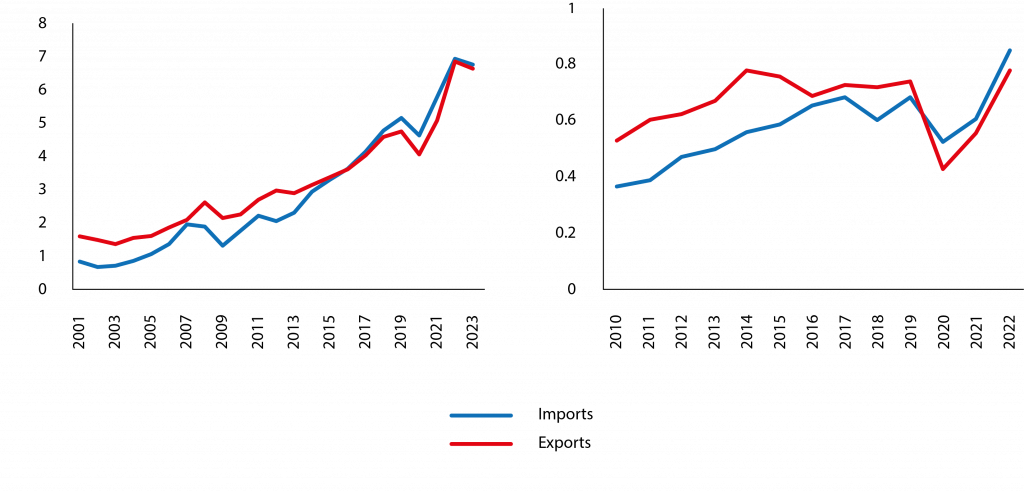

Figure 4. EU27 trade in goods with WBs (left) and EaP countries (right), € billions

Note: See Annex 2 for data disaggregated by country.

Source: Bruegel based on Eurostat (DS-018995).

How do the agreements facilitate market integration? The WB SAAs have eliminated tariff barriers with the EU to a great extent, and trade with the region has grown by almost 130 percent over the past 10 years.

Figure 5 confirms that trade between the EU and WB has grown in absolute terms (though did not further increase the already high levels in relative terms, Figure 1), and there is no indication of being outpaced by the Eastern Partnership countries. Yet, non-tariff barriers (NTBs) remain significant – both barriers with the EU and within the Western Balkans region.

NTBs can generally be associated with technical regulations, customs procedures, licensing requirements and other regulatory obstacles, all of which limit trade through increased costs, delays and administrative burdens.

For example, the waiting and processing time only at crossing points in CEFTA states generates between €250 million and €300 million in costs annually (World Bank, 2015). While reliable data on the scope of NTBs is limited, some proxies indicate their presence.

For instance, World Bank Trading Across Barriers data points to higher costs, both financial and in terms of time taken, associated with border and documentary compliance for importing goods to the Western Balkan countries, than to the EU or high-income OECD countries (Annex 5). While the same data limitations make it difficult to identify non-tariff barriers in EaP countries, the consensus is that they also pose challenges to trade in these countries.

Comparative legal analysis of the treatment of NTBs reveals a more detailed legal regime in the Ukraine DCFTA in three respects. First, the Serbia SAA does not foresee a non-discrimination rule regarding non-tariff measures, while the Ukraine DCFTA established a national treatment rule (Article 34).

It has been argued that the current legal reference to freedom of goods in the SSA should be interpreted in line with EU law and would thus suffice to ban non-tariff barriers (Sretić, 2023).

Second, the Ukraine DCFTA explicitly addresses technical barriers to trade (TBTs), in particular the “adoption and application of technical regulations, standards, and conformity assessment procedures” (Article 53).

Again, the Serbia-SAA is silent on the treatment of technical barriers to trade. The CEFTA addresses TBTs and provides for a governance structure to minimise them (Article 13). There have been further attempts to address NTBs in the WB intra-regional integration process. For example, the Common Regional Market (CRM) has established green lanes at borders within the region.

Through better exchange of customs data before goods arrive at crossing points, the transit times for goods have greatly reduced (European Commission, 2023a). The draft Growth Plan, while requesting alignment with EU standards, does not foresee a regime to address further eradication of NTBs.

Yet overall the lack of salience of TBTs in the SAAs does not correspond to the significance of this source of impediment to market integration. Estimates suggest that a three-hour reduction in waiting times is the equivalent of a 2 percent reduction in tariffs (Del Mar Gomez et al 2023).

The OECD has considered the trade reducing effects of being outside the single market associated with TBTs and sanitary and phytosanitary measures (SPS) measures, suggesting these costs amount to 50 percent of the ad-valorem equivalent of measures on goods imported into the European Union from third countries (RCSPI, 2023). We infer that NTBs remain under-addressed at the level of the SAA agreements between WB countries and the EU.

Reducing NTBs is pivotal. Slow customs procedures are often the result of lacking infrastructure. For example, electronic payment of duties and charges and pre-arrival processing are essential infrastructure elements, lacking in all CEFTA economies. Serbia and Montenegro are reported not to offer the option of paying the fees for exports online (GIZ, 2022).

As argued above in relation to crossborder infrastructure and networks, infrastructure facilitating customs procedures should qualify for EU funding without (or with limited) conditionality, because the positive intra-regional economic effects are significant. The EU should allocate financial resources to the modernisation of such facilities, in particular infrastructure that facilitates the payment of duties, taxes and other fees for the importation process.

In addition, mutual recognition also helps to reduce waiting times caused by scanning procedures and sample testing. The EU has created separate lanes with WB countries, and the same practice should be applied between WB countries (GIZ, 2022).

Again, where EU funding could facilitate this, there should be unconditional support for expanding joint crossing point facilities and establishment of separate lanes.

Likewise, concerning intra-regional commerce with ‘mutual recognition’ having proved itself as a motor for fostering intra-EU trade, WB countries should pursue recognition of conformity assessments procedures across the CEFTA region. The CEFTA provides the framework for this both in the field of SPS measures and NTBs more generally, but the available legal space under the agreement for eradicating NTBs (Articles 12, 13 CEFTA) should be exploited further.

In particular, Article 13 para. 4 CEFTA paves the way for WB countries to implement “mutual recognition of conformity assessment procedures”, offering a powerful tool for eliminating non-tariff barriers.

Finally, the EU should see advantages for itself not only in liberalising access to the internal market but also in outbound investment into the WB region. Access to the EU internal market and EU-financed crossborder infrastructure would reduce WB dependence on geopolitically risky partners.

For example, given Serbia’s persistent dependence on Russian energy supplies, the EU should integrate the WB into its energy internal market by fostering the construction of electricity and gas connections – in the EU’s own best interest and without conditionality.

At a time when economic security is becoming so important, helping to integrate the WBs into the supply chain could be very useful and help reduce dependencies. The Trans-Balkan electricity corridor is a good example23, but further energy-oriented EU investments efforts could be directed to financing solar-energy capacity in the Western Balkans or wind and hydropower projects (Ghodsi et al 2022).

The EU can also do more to provide loan guarantees and investment incentives for private firms to invest in infrastructure in the region, in addition to tying this to reform and green agenda benchmarks. With EIB and ERBD expanding targeted loan guarantees to firms investing in these areas, the investment potential would be increased (Ghodsi et al 2022).

The draft Growth Facility aims at accelerating the green transition towards decarbonisation and to boost innovation, particularly for SMEs and in support of the green transition, yet no reference is made in the draft Facility to technological and industrial support to that end.

Energy-related infrastructure is an important policy field in view of the politically controversial energy dependence of WB countries on Russia (in particular Serbia). However, the CEFTA agreement is silent on issues of infrastructure, energy or gas supplies, leaving untapped a natural area of cooperation.

While integration into Europe’s energy markets is part of the goals under the Serbia SAA (Article 109), there is no provision for translating these goals into substantive market access and specific cooperation obligations.

By contrast, the Ukraine DCFTA offers a comprehensive and substantive regime on energy, covering, inter alia, prohibition of trade-restrictive measures and striving for the emergence of energy markets (Article 338).

As long as there is no integration into EU energy markets in the WB, trade in energy will be constrained significantly by insufficient investment in transmission infrastructure and production capacity. China and Russia are likely to fill a void left by the EU, using state-driven investments in essential infrastructure in the WB (Stanicek, 2022).

Against this background, a proposal worth exploring on the level of implementation is to integrate the Western Balkans fully into the EU emissions trading system (ETS), which would accelerate the energy transition in the WB and be a significant new source of funding (Egenhofer, 2023).

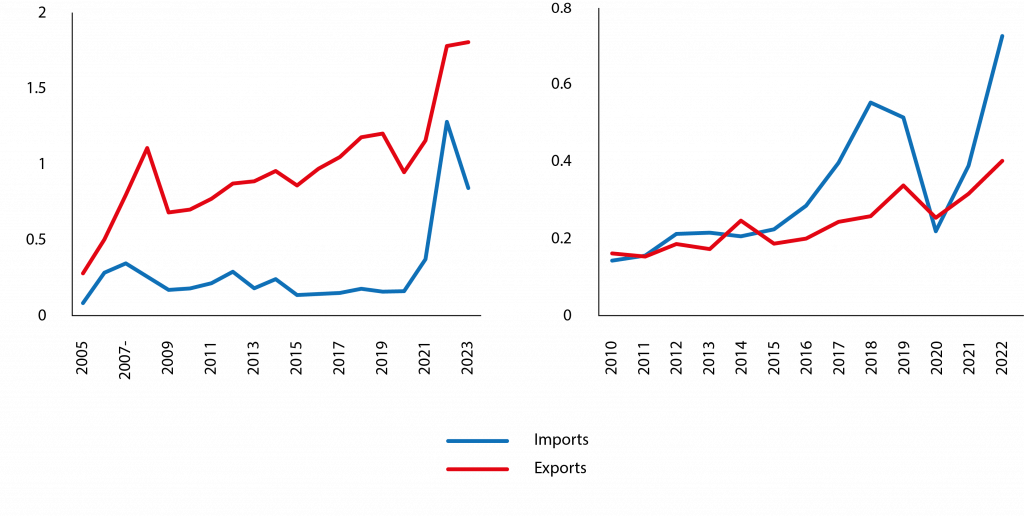

2.3 Freedom of services

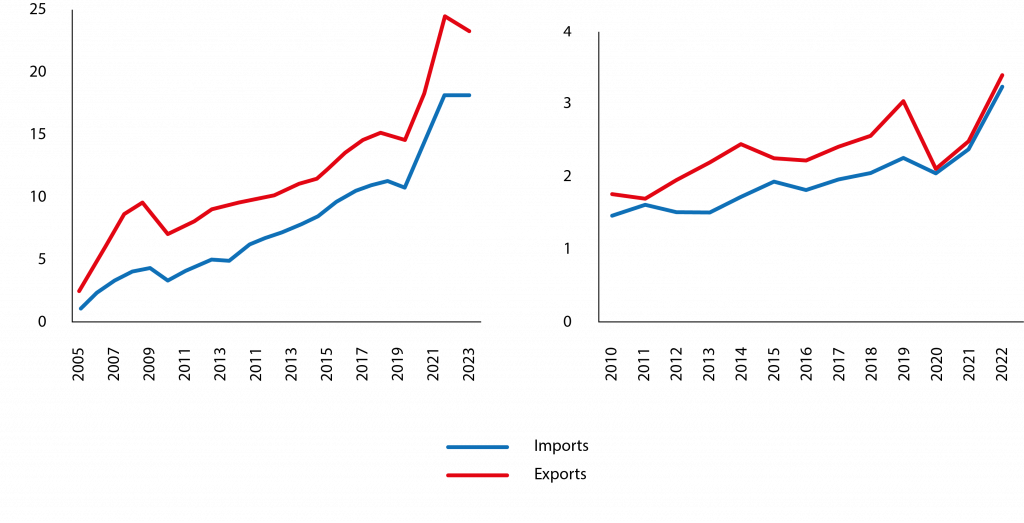

From a comparative perspective, data on trade in services shown in Figure 6 indicates that WB services trade with the EU has grown less quickly than goods trade (compare with Figure 4). Also, EU services exports have grown more quickly with the EaP than with the WB, though from a very low basis.

One reason for this may be associated with the shortcomings in unleashing the potential of services, which can be illustrated by the inferior treatment of services in the Western Balkans SAAs compared to the Ukraine DCFTA. The EU-Ukraine DCFTA establishes a non-discrimination standard for Ukrainian services provided in the EU.

Specifically, these services must be granted “treatment no less favourable” than EU domestic services (Articles 93, 94). While this does not apply to all services, it extends to an extensive list of services. Consequently, the available evidence on Georgia supports the idea that its services sector has been expanded, with exports more than doubling in size since the entry into force of the DCFTA between 2014 and 2019 (Akhvlediani et al 2022).

Figure 5. EU27 trade in services with the Western Balkans (left) and EaP (right), € billions

Note: Data for Kosovo is not available. Data is presented from the perspective of the EU. See Annex 2 for data disaggregated by country.

Source: Bruegel based on Eurostat (bop_its6_det).

The Serbia SAA does not stipulate a no-discrimination principle similar to the Ukraine DCFTA. The Serbia SAA provides that the EU may not take measures that are “significantly more restrictive” than the situation before the Serbia SAA. It also provides procedurally for the EU and the WB to engage in “steps to allow progressively the supply of services.”

Yet, this procedural potential has not so far been exploited, while substantive law liberalisation of services remains weak compared to the non-discrimination rule under the DCFTAs. Even the CEFTA does not provide unconditional liberalisation of services on intra-regional level.

The legal comparison points at the absence of rules providing for substantive discrimination prohibitions and the lack of regulatory harmonisation. This contrasts with the non-discrimination clearly spelled out in the agreement on trade in goods. Regulatory harmonisation (or mutual recognition) would be particularly beneficial in core service areas of the region, such as travel and transportation (RCSPI, 2023).

2.4 Capital movement

The EU accounts for approximately 60 percent of the current FDI stock in the Western Balkans24, but there is no indication that FDI is treated more favourably in either the Western Balkan or the countries of Eastern Partnership.

The rules laid down in the relevant agreements indicate a high degree of capital movement freedom. Established through a ban on discrimination, capital movement is guaranteed both in the WB (Article 63 Serbia SAA) and in the Ukraine (Article 145 Ukraine DCFTA). Both types of agreements explicitly extend the free movement of capital to direct investments.

However, specific relevant sectors enjoy less-favourable treatment in the WB. For the financial sector, for example, DCFTA agreements offer an elaborate regime to promote the access of European investment in the Eastern partnership countries.

Access is granted to payment systems (Article 132 Ukraine DCFTA), regulatory approximation is required (Article 133) and bans on discrimination exist (Article 128). By contrast, the WB SAAs emphasise that financial services are subject to significant restrictions (Articles 54, 56 Serbia SAA).

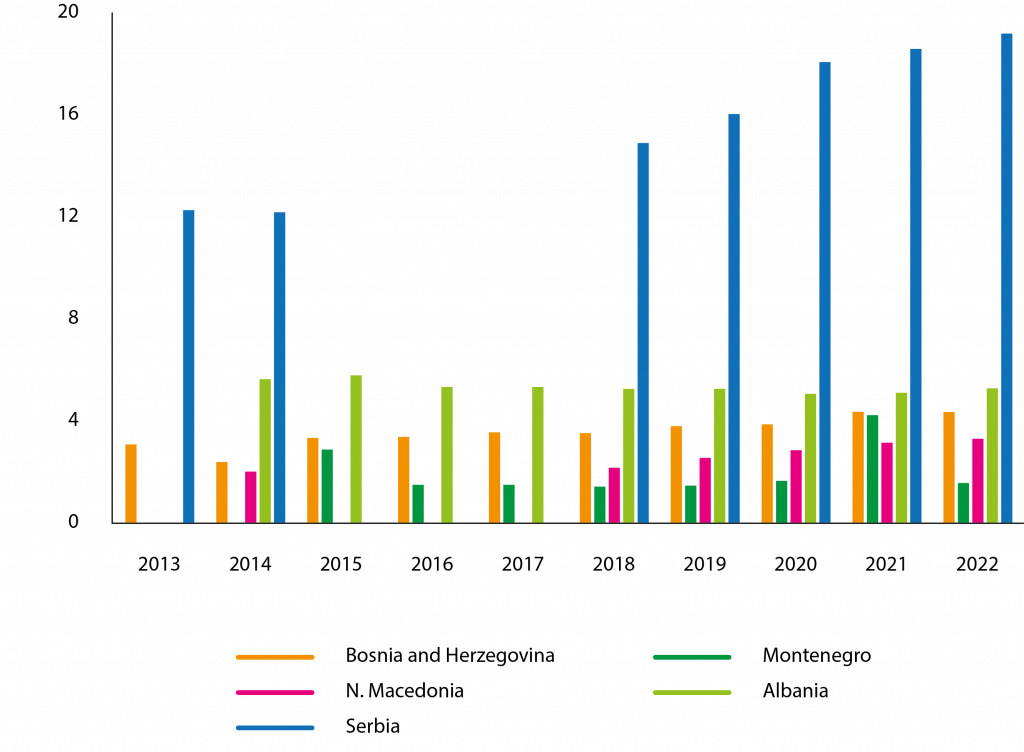

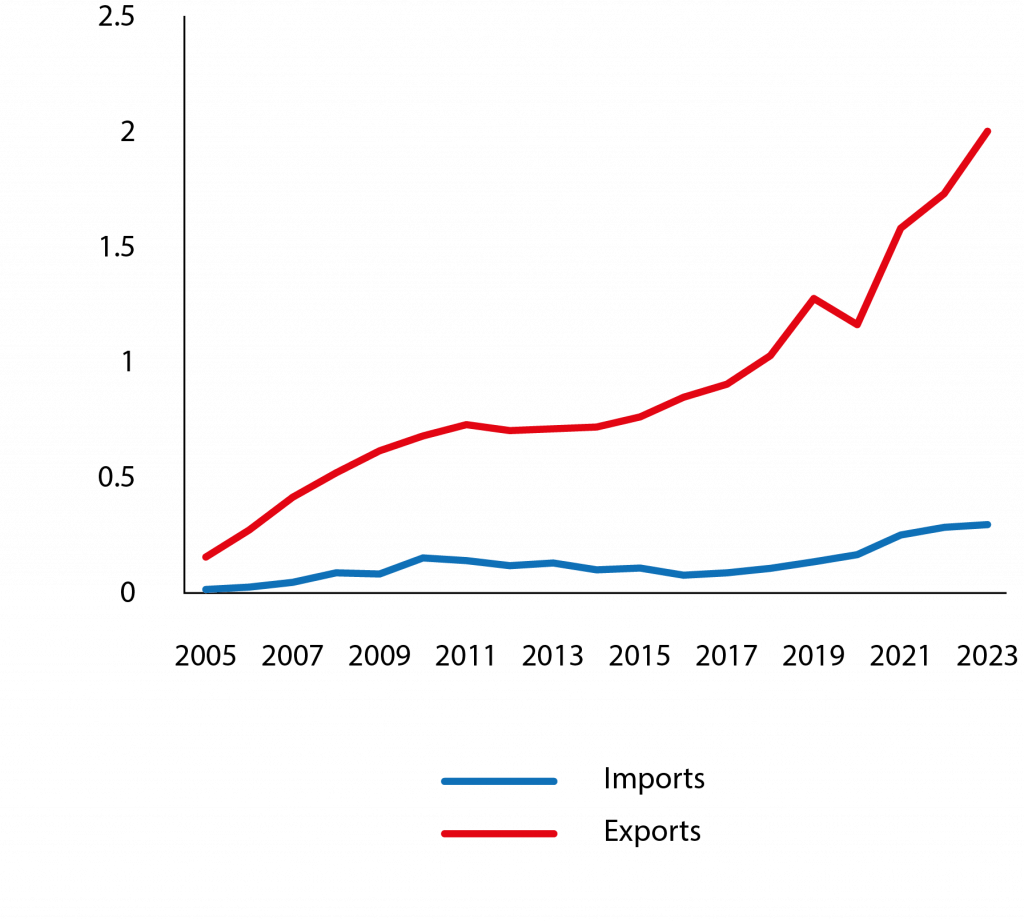

Figure 6 shows that, much like for trade, EU FDI in the two regions is mainly into Serbia and Ukraine respectively (however, see Annex 3 for a breakdown of EU FDI into the various countries as a share of their GDP)25.

Figure 6a. EU27 FDI stock in the Western Balkans (€ billions)

Figure 6b: EU27 FDI stock in the EaP (€ billions)

Note: The lack of data in some years is due to data not being reported by Eurostat for confidentiality purposes.

Source: Bruegel based on Eurostat (bop_fdi6_geo).

The evidence suggests that FDI could be driven, more than the other freedoms we have discussed, not only by the openness of market access but by factors beyond the absence of barriers to moving capital. This is also evidenced by the experience of Bulgaria and Romania.

Both saw a one-time surge in FDI after accession to the EU, but have remained at pre-accession levels since. Rather, factors associated with state-driven investment and geopolitical competition have significant effects on FDI in the WB. The EU has historically been the dominant investor in the WB (See Annex 3).

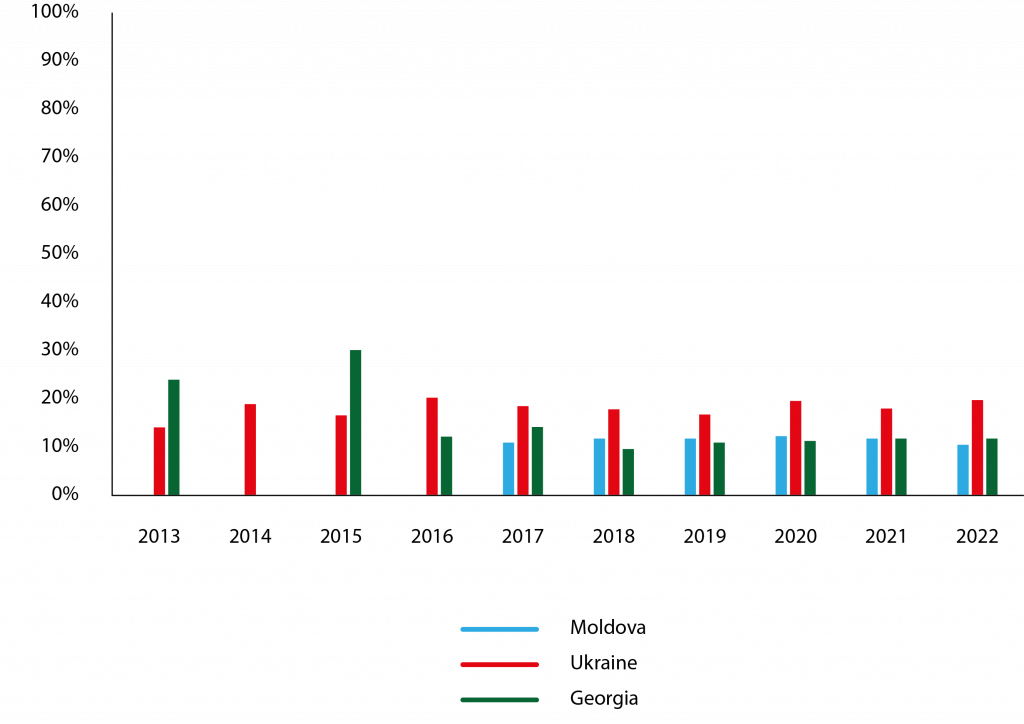

Figure 7. Share of net FDI flows to Serbia, 2010-2022

Note: The variable reported is the share of the EU27 and China net FDI in overall net FDI in Serbia. Net FDI is calculated as the difference between assets (Serbian residents’ investments abroad) and liabilities (non-residents’ investments in Serbia). Over this period there was consistently a larger inflow of investment into Serbia than outflow. This figure shows the share of that net inflow of FDI that comes from the EU27 and China.

Source: Bruegel based on National Bank of Serbia26.

In any case, a legal regime that secures non-discriminatory treatment of capital movement does not offer a complete picture on possible vulnerabilities related to FDI. This is so because state-funded, non-EU foreign investment increasingly outcompetes EU private investment. Some research points to a growing Chinese investment footprint in the region, especially in Serbia (Vulović, 2023; Bykova et al 2022), which seems to be driven by state-owned investors or by state-guaranteed finance linked to contract guarantees for Chinese companies (Ghodsi et al 2022).

Indeed, this increase in Chinese investment in Serbia is supported by China’s growing share in net FDI flows to Serbia (Figure 7).

Dependence on countries perceived (from a European perspective) as geopolitical rivals increases the WB’s vulnerability to geopolitical turmoil. A high EU share of FDI in turn should align EU and WB interests.

Furthermore, from the EU perspective, FDI in WB is self-serving, as one element of a ‘de-risking’ strategy, put in place by incentivising European firms to shift production closer to home, with the Western Balkan as one region in which geopolitical competition takes place.

As mentioned above, the ERBD and EIB can play an important role in promoting EU FDI in the region and in maintaining the FDI-based ties between the EU and WB, thus sidelining investment from geopolitical rivals. Through these institutions, the EU should develop and enhance the capital market in the region, in particular by stimulating investment by smaller firms in the region (Ghodsi et al 2022).

Both EU outbound investment promotion and inbound investment control can play roles here. Outbound EU investment to WB has positive implications (both for the EU and WB countries) beyond market opportunities and should be promoted through available incentivising instruments, while WB inbound investment control becomes increasingly important in light of the state-driven and strategic investment of China and Russia in the region.

The existing EU inbound investment control regime should be treated as relevant acquis that should enjoy priority in implementation in the WB. This would help to identify (and divert) state-driven acquisitions that could ultimately increase WB dependence and vulnerability.

Within the WB bloc, this implies that EU and WB countries must develop regional guidance on screening mechanisms that respond to FDI in line with the EU investment control regime.

2.5 Approximation of laws

Another comparative imbalance between the WB and eastern European countries are their variable commitments on the approximation of laws. While the EU generally makes the adoption of the acquis an ex-ante precondition for access to the internal market, there are significant differences in how this obligation is put in place substantively and in governance structure.

Approximation of laws forms an essential element of the SAAs, which provide for seamless access to the internal market for goods originating from WB countries based on a sufficient alignment of national rules with the Union acquis.

Specifically, the WB SAAs “recognize the importance of the approximation to that of the Community” (Article 72 Serbia-SAA) and they provide for a governance structure that aims at promoting the approximation process.

What is missing beyond this general obligation is a more detailed enumeration of specific legal texts to be adopted and by when. Likewise, CEFTA provides a governance structure on “harmonization of technical regulations and standards” in the field of TBTs (Article 13 of CEFTA) but remains silent on substantive obligations and concrete legal texts.

This contrasts with the extensive approach on the approximation of laws under the DCFTA agreements, which specify the approximation of laws for individual policy areas (rather than one single encompassing global obligation).

In the DCFTAs, the agreements are much more explicit, with the listing of hundreds of directives and regulations that the Eastern partnership countries are required to implement.

Take public procurement as a specific example. The Georgia DCFTA provides for a gradual approximation of public procurement legislation in Georgia with the Union public procurement acquis based on the specific EU procurement law (Article 141 Georgia DCFTA), and it requires further approximation with the Union’s public procurement acquis (Article 146 Georgia DCFTA).

In essence, while the WB SAAs rely on a procedural framework to pursue approximation of law (through cooperation), the DCFTA agreements, in addition to a procedural framework, specify substantively the specific approximation obligation.

Evaluation of the Georgian experience shows that the gradual approximation to EU norms in public procurement improved the already reformed system (Akhvlediani et al 2022).

The higher degree of specificity in terms of the obligation to approximate the laws is also a result of a continuous practice of amending the SAAs. The Ukraine SAA has been modified and extended by new or revised Annexes to the SAA around ten times since 2018, while the Serbia AA has been amended in the same time period only once.

One reason for this difference could lie in the more compelling approximation ambition in the EaP SAAs. For example, the Ukraine SAA contains special approximation provisions for the areas of sanitary and phytosanitary and animal welfare legislation, as well as for telecommunications – these specific approximation obligations have been used to amend and further develop the Ukraine SAA. In turn, the Serbia SAA is limited to a general approximation provision but largely lacks more specific obligations.

3 Comparative assessment of governance deficiencies

While integration into the internal market is primarily an issue of substantive requirements on market access, governance is essential in implementing effectively the commitments under the agreements.

The governance structure common to SAAs typically involves an SAA Council as political body, with high-level representatives of both the EU and the country in question, tasked to supervise and evaluate the integration process. A Stabilisation and Association Committee composed of high-level civil servants supports and prepares the work of the SAA Council. Sub-committees involving civil servants meet at technical level throughout the year to discuss and monitor progress on specific subject areas covered by the SAA.

There is also a joint SA Parliamentary Committee, involving members of the national parliament and of the European Parliament, from across the political spectrum. These joint institutional structures manage the process by jointly overseeing the implementation of the SAA.

3.1 Political dialogue and civil society

With the WB as a region characterised by multiple historical and contemporaneous internal political tensions (Domi, 2023), the political dialogue as a reconciliatory and inclusive element for integration of the WB into the EU single market is key when it comes to effective implementation of the agreements.

The EaP countries and the WB have established structures of political dialogue that serve to address political and technical issues impeding implementation and deepening cooperation. Dialogue can take place at different political and technical levels between the EU and the region (Annex 1).

Building on the general governance institutions mentioned above, a number of additional formats subsequent to the initial governance under the SAAs have been initiated. Intra-regional governance is put in place through the Regional Common Council (RCC) Secretariat under the Regional Common Market initiative, in cooperation with the CEFTA Secretariat.

The different institutions perform different functions, either inter-regionally to foster convergence with the EU, or intra-regionally between WB countries.

A core difference and shortcoming of the WB structures, compared to the relationship between the EU and the EaP countries, is the absence of civil-society involvement in the framework of implementing the agreements.

Civil society plays an important role in various ways: civil society is a carrier of expertise feeding into implementation of commitments; civil society is key in identifying and eliminating barriers to trade; it collects relevant information to provide to the bodies engaging in trade facilitation or rules approximation.

Civil society also has an important and disciplining surveillance function over governmental decision-making. Also, civil society is one of the groups affected by democratic backsliding in some of the WB countries, undermining the ability of civil society to monitor government action.

The sufficient integration of civil society into the governance structure of the SAA (and the EU Growth Plan) can thus be likened to the Copenhagen Criteria for EU accession, for which involvement of civil society without political and administrative pressures is indispensable.

In that respect, the Ukraine DCFTA establishes a comprehensive structure for political dialogue involving civil society. The EU and the DCFTA countries are obliged “to involve civil society in the implementation of the agreement”, to encourage mutual exchanges of experiences and multiple other forms of connecting civil society among each other, as well as with decision-makers (Articles 443, 444, SAA Ukraine). It even creates policy-specific civil-society exchanges, such as for trade and sustainability issues (Article 299, SAA Ukraine).

By contrast, the relevant agreements involving the WB are silent on the role of civil society. The WB SAAs do not assign a task to civil society, nor has CEFTA integrated civil society into the implementation process, nor does the Working Programme of the Common Regional Market27 identify civil society as a relevant contributor to the implementation process.

In addition and likewise, the EU does not seem to attach much value either to civil-society involvement. Its draft Growth Plan foresees a role for civil society only at the evaluation stage, and only as one of many stakeholders (Article 25 of draft Growth and Resilience Facility).

The limited role of civil society in implementing the WB SAA is insufficient and forgoes benefits, both from the perspective of relevant expertise as well as a source of legitimacy and acceptance.

Again, Georgia can be referred to as a positive example in this respect. The Georgia SAA established a Civil Society Platform, which enables civil-society organisations from both sides to monitor the implementation process and prepare their recommendations to the relevant authorities.

Specifically, the Georgian National Platform of the Eastern Partnership Civil Society Forum was established in 2015 as a consultative body under the Association Agreement. It brings together up to 200 organisations, among them civil-society organisations, employee organisations, trade unions and associations.

Not only does this platform perform a bottom-up process of providing insight, but it also assures the monitoring of the AA/DCFTA’s implementation by producing recommendations to the Association Council and the relevant authorities of both parties (Akhvlediani et al 2022).

3.2 The DCFTA Trio format as role model?

There is no shortage of political bodies created under the agreements and involved in the process. Association Agreements, CEFTA, the Common Regional Market Initiative – bodies abound, yet they remain deficient. CEFTA’s governance structure lacks the enforcement capacity that other trade agreements with similar scope of ambition have.

CEFTA is designed in intergovernmental fashion, it has not created institutions endowed with competences to make legislative proposals, nor does it exercise adequate supervision over the implementation of the agreement.

While the CEFTA Secretariat is largely limited to providing technical and administrative support to the CEFTA Joint Committee and Bodies, the latter are plagued by the need to decide by consensus and are riddled by political controversies over the representation of Kosovo (RCSPI, 2023).

To some extent, the Common Regional Market initiative sought to create the missing element. The RCC Secretariat created under this framework (including countries such as Turkey and Greece) coordinates and monitors the Action Plan in close cooperation and consultation with CEFTA Secretariat.

While dialogue, reconciliation and cooperation characterise the work of the RCC, its success is limited because of the participation of countries beyond the WB, including the geopolitical rival Turkey, which limits the possibility for this governance framework to focus on the specific concerns of the WB countries in relation to the EU.

Drawing from the experience of the EaP countries, there is a need for a political framework dedicated to the joint WB endeavour for EU accession. The ‘new frontrunners’ – Ukraine, Georgia and Moldova – motivated but disappointed about the slow accession process, created an Associated Trio format in 2021 to push harder to “enhance their political association and economic integration with the EU”, in line with their European aspirations28.

The Trio format was complementary to the multiple other formats and bodies established under the Eastern Partnership, but it was complementary in a productive way by offering an agenda for the dialogues between the ‘Association Trio’ and the European Commission, in addition to the DCFTA-related issues, one that deepened cooperation in areas including transport, energy and green economy, even if the Trio has its own shortcomings and the war in Ukraine has hampered the effectiveness of this institution.

Taking the Trio format of the DGFCA countries as role model, it is worth exploring an equivalent body as a complementary element to the multiple existing formats and bodies of the Western Balkan. While WB states maintain their individual agreements with the EU, there is no sufficiently visible format that focuses on the joint WB concerns in pursuing EU accession.

Just as the Trio format of DGFCA countries established ad-hoc trilateral consultations to discuss specific issues in the framework of their integration with the EU, a similar institutionalisation could promote the concerns of the WB beyond the SAAs and the Growth Plan framework.

Such a framework could establish ‘Trio’ coordinators within the Ministries of Foreign Affairs, and coordinate meetings at expert, senior official and, when appropriate, ministerial levels.

The Open Balkan Initiative (OBI) could be a first step in this direction. Intended to intensify the economic integration between three WB countries (Albania, North Macedonia and Serbia), this initiative could grow further to become a representative body that represents WB interests in relation to the EU.

The initial motivation for the OBI arose from fatigue with the sluggish EU integration process, but it could become a productive forum by accelerating intra-regional economic integration, political cooperation in the areas of infrastructure and transport, and the fight against organised crime and terrorism (Semenov, 2022).

There is the potential that the EU finds a counterpart able to speak with one voice for WB countries. Yet, in its current setup, the OBI is not able to compensate for one of the core deficiencies of the cooperation frameworks under CEFTA and the Common Regional Market, which is the absence of an independent institution tasked with overseeing and implementing agreements, and which ensures consistent implementation across countries and alignment with the EU acquis (RCSPI, 2023).

4 Conclusions

The importance of EU single market membership to WB economic prospects cannot be overstated. This analysis sought to highlight differences between WB SAAs and DCFTAs and lessons to learn from the DCFTA process. It showed that the DCFTAs apply a more lenient approach to intra-regional cooperation.

Also, the DCFTAs subject non-tariff barriers to a more explicit regime than WB SAAs; rules governing trade in services incorporate a stronger non-discrimination standard; and the DCFTAs offer a more rigid and comprehensive approach to the approximation of laws than the WB countries. It is the latter point in particular that underscores the different integration models underpinning the WB SAAs and the DCFTAs.

The WB SAAs were initially concluded with the prospect of addressing the adoption of the acquis during the subsequent accession negotiations (which then turned out to be delayed), rendering SAAs in some aspects less ambitious.

In turn, conclusion of the DCFTAs with the EaP countries was seen as a substitute for EU accession, which explains the (in parts) greater degree of trade liberalisation in the EaP countries than in the WB, and the more assertive stance of these agreements in particular on approximation issues.

There is no indication that the differences in legal governance have translated into a stronger economic performance in the EaP countries compared to the WB. From a comparative perspective, the analysis suggests that dubbing Ukraine and other EaP countries as the ‘new frontrunners’ appears premature if not misleading. Rather, they can be dubbed ‘quickstarters’, reflecting their rapid pace in moving from application status to candidate status and accession negotiations.

The WB remains significantly more integrated in trade with the EU than the EaP countries, while convergence with the EU has been stagnating both for the WB and the EaP. While not underperforming compared to the EaP countries, economic deficiencies in the WB nevertheless exist and should be addressed.

Conditionality attached to both internal market and EU funding should be nuanced; above all, in relation to economic intra-regional integration, it should not impede the necessary investments. The eradication of non-tariff barriers should enjoy priority both inter-regionally with the EU and intra-regionally between WB countries.

The EU’s levers for promoting investment in the region should be further enhanced, a demand that is further reinforced by geopolitical concerns about Chinese investments coming without EU-type conditionality attached, and thus creating a tempting alternative for WB countries that have been increasingly disappointed with the slow progress in EU accession.

The question is whether and how the identified shortcomings in the agreements should be addressed. One avenue is to seek amendments of the SAAs and adjust according to the shortcomings identified in this analysis, which implies bargaining with the EU on amending the SAAs on a country-by-country basis. Such a formal amendment approach is likely to undermine the negotiation stage of EU accession (into which five out of six WB states have entered).

Amending the SAAs with a view to aligning them with the DCFTAs would in the WB region be perceived as a (disappointing) substitute for EU accession. An alternative would be to seek an agreement that is complementary to the existing ones, concluded between WB countries (negotiating in unity) on the one side and the EU on the other side.

This approach would be in line with the above exploration of a joint body as a counterparty to the EU. However, the existing and persistent intra-regional political tensions make a sufficiently homogenous stance, as a precondition for crafting a joint agreement, an unlikely prospect.

A third and more pragmatic solution would be to use the existing framework to the greatest extent possible. For example, regulation of trade in services gives leeway to the SAA Council to “take the measures necessary to progressively” liberalise the supply of services (Article 59 Serbia SAA). In addition, the SAA Council has sufficiently wide procedural leeway to widen the scope of interaction with civil society and to create space for civil society in the implementation of the SAAs (Article 120 Serbia SAA).

In turn, the EU is more flexible in unilaterally adjusting its policies on the WB. It could nuance the conditionality embedded in its draft Growth Plan and the draft Growth Facility, and it can extend its tools to foster investment in the regional infrastructure, and thus contribute to stronger convergence by the region.

Endnotes

1. Lisa O’Carroll, ‘As Ukraine and others queue to join, is EU ready for enlargement?’ The Guardian, 31 August 2023.

2. Services data is missing for Kosovo.

3. Based primarily on European Commission (2023c) and the latest relevant Reports and Conclusions from the European Commission and Council, available for each country; other sources referenced as appropriate.

4. For more details, see ‘Treaty on European Union — Joining the EU’.

5. Despite Council agreement to begin negotiations with Albania and North Macedonia in March 2020, the process only began for each country in July 2022.

6. See European Commission news article of 8 December 2023, ‘Screening meetings completed as part of screening process with Albania and North Macedonia’.

7. Meaning that it “should be offered official candidate status when it is ready”; see https://neighbourhood-enlargement.ec.europa.eu/enlargement-policy/steps-towards-joining_en.

8. See footnote 6.

9. See point 16 in European Commission (2023c).

10. See point 15 in European Commission (2023c).

11. Based on media reports; see for instance Alexandra Brzozowski, ‘EU Commission to start screening process for Ukraine, Moldova after ‘surprise’ delay’, Euractiv, 17 January 2024.

12. See point 14 in European Commission (2023c).

13. See ‘Stabilisation and Association Agreement with Serbia’.

14. See Association Agreement between the EU and Ukraine.

15. See Majlinda Bregu, Secretary General of the Regional Cooperation Council, speaking at the 10th Belgrade Security Forum, 22 October 2020.

17. See https://www.berlinprocess.de/.

18. Which also includes factors such as the efficiency of the clearing process and the ability to track and trace consignments. For more details see https://lpi.worldbank.org/.

19. Bulgaria, Czechia, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia.

20. As well as political tensions and institutional factors, for example.

21. See European Commission news article of 13 December 2023, ‘European Commission announces additional €680 million investment package for the Western Balkans under the Economic and Investment Plan’.

22. Christian Danielsson, Director-General for Neighbourhood and Enlargement Negotiations, speaking on 3 March 2020. See Strategeast, ‘EU welcomes Ukraine’s progress in implementing the Association Agreement and the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area’, 4 March 2020.

23. See EU Projects in Serbia, ‘The Trans-Balkan electricity corridor’.

24. See Council of the EU, ‘The EU: main investor, donor and trade partner for the Western Balkans’.

25. FDI data is problematic, given the opacity of the ultimate investor behind the FDI in question. To address these concerns, in Annex 3 we build on the work of Damgaard et al (2019), who used firm-level data to estimate the “ultimate investor economy” in FDI data.

26. See ‘Foreign direct investments, by country, 2010-2022 (BPM6)’.

27. Available from: https://neighbourhood-enlargement.ec.europa.eu/enlargement-policy/policy-highlights/common-regional-market_en.

28. See Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine, ‘Association Trio: Memorandum of Understanding between the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Georgia and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and European Integration of the Republic of Moldova’, 17 May 2021.

29. Source and notes are consistent for each figure in this section.

30. Eurostat does not provide services data for Kosovo.

References

Akhvlediani, T, S Blockmans, J Bryhn, L Gogoberidze, D Gros, W Hu, I Kustova and F Shamsfakhr (2022) Ex-post evaluation of the implementation of the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area between the EU and its Member States and Georgia, Centre for European Policy Studies.

Blockmans, S (2018) ‘Georgia’s European Way: What’s Next?’ Policy Paper, Eastern Partnership Civil Society Forum, 27 July.

Bykova, A, B Jovanović, O Pindyuk and N Vujanović (2022) ‘FDI in Central, East and Southeast Europe’, Monthly Report, May, wiiw.

Dabrowski, M (2014) ‘EU cooperation with non-member neighbouring countries: the principle of variable geometry’, CASE Network Reports 119, Center for Social and Economic Research.

Dabrowski, M (2022) ‘Towards a New Eastern Enlargement of the EU and Beyond’, Intereconomics 57(4): 209-212.

Damgaard, J, T Elkjaer and N Johannesen (2019) ‘What Is Real and What Is Not in the Global FDI Network?’ Working Paper WP/19/274, International Monetary Fund.

Darvas, Z, M Demertzis, C Martins, N Poitiers, L Léry Moffat, E Ribakova and B McWilliams (2023) EU trade and investment following Russia’s illegal invasion of Ukraine, Study for the European Parliament INTA Committee.

GIZ (2022) Report on Non-Tariff Measures in CEFTA, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ).

Domi, TL (ed) (2023) Western Balkans 2023: Assessment of Internal Challenges and External Threats, New Lines Institute.

Egenhofer, C (2023) ‘The solution to phasing out coal in the Western Balkans?’ CEPS Policy Brief 2023-04 Centre for European Policy Studies.

European Commission (2022a) ‘Commission Opinion on the Republic of Moldova’s application for membership of the European Union’, COM(2022) 406 final.

European Commission (2022b) ‘Commission Opinion on Ukraine’s application for membership of the European Union’, COM(2022) 407 final.

European Commission (2023a) ‘New growth plan for the Western Balkans’, COM(2023) 691.

European Commission (2023b) ‘Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on establishing the Reform and Growth Facility for the Western Balkans’, COM(2023) 692 final.

European Commission (2023c) ‘2023 Communication on EU Enlargement Policy’, COM(2023) 690 final.

European Commission (2023d) ‘Kosovo* 2023 Report Accompanying the 2023 Communication on EU Enlargement policy’, SWD(2023) 692 final.

Ghodsi, M, R Grieveson, D Hanzl-Weiss, M Holzner, B Jovanović, S Weiss and Z Zavarská (2022) ‘The long way round: Lessons from EU-CEE for improving integration and development in the Western Balkans’, Joint Study No. 2022-06, wiiw and BertelsmannStiftung.

Mihajlović, M, S Blockmans, S Subotić and M Emerson (2023) Template 2.0 for Staged Accession to the EU, Open Society Foundations.

RCSPI (2023) A Proposal for a New Approach to the Western Balkans-EU Relationship, Regional Center for Strategic and Political Initiatives.

Semenov, A (2022) ‘Open Balkan: Objectives and Justifications’, Comillas Journal of International Relations 24.

Sretić, Z (2023) ‘Sectoral integration opportunities in the SAA regime’, Issue Paper, June, Open Society Foundations.

Stanicek, B (2022) ‘China’s strategic interests in the Western Balkans’, Briefing PE 733.558, European Parliamentary Research Service.

Vulović, M (2023) ‘Economic Relations between the Western Balkans and Non-EU Countries’, SWP Comment 2023/C 36, Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik.

World Bank (2015) The Regional Balkans Infrastructure Study (REBIS) Update, Enhancing Regional Connectivity, Identifying Impediments and Priority Remedies.

This article is based on a Bruegel Working Paper that was produced with financial support from The Open Society Foundations Western Balkans. The author thanks Conor McCaffrey for research assistance, along with Marek Dabrowski, Zsolt Darvas, Heather Grabbe and André Sapir for their valuable comments and suggestions.

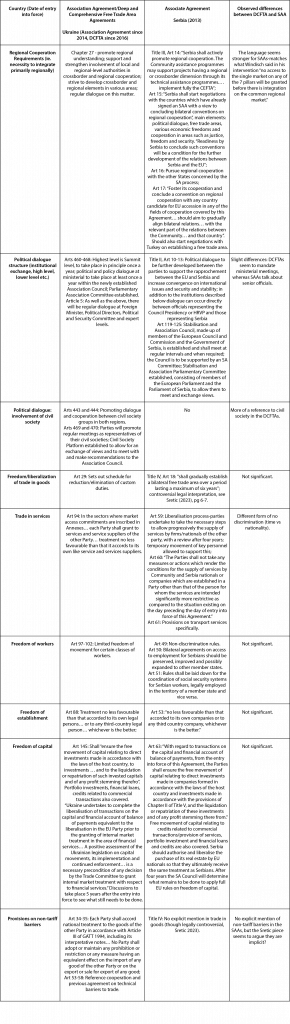

Annex 1. Legal comparison

Annex 2. Trade data

EU27 goods (left) and services (right) trade with Albania (€ billions)

Note: Exports refer to EU exports to Albania and imports the reverse29.

Source: Bruegel based on Eurostat (DS-018995).

EU27 goods (left) and services (right) trade with Bosnia and Herzegovina (€ billions)

EU27 goods (left) and services (right) trade with Georgia (€ billions)

EU27 goods30 trade with Kosovo (€ billions)

EU27 goods (left) and services (right) trade with Moldova (€ billions)

EU27 goods (left) and services (right) trade with Montenegro (€ billions)

EU27 goods (left) and services (right) trade with North Macedonia (€ billions)

EU27 goods (left) and services (right) trade with Ukraine (€ billions)

EU27 goods (left) and services (right) trade with Serbia (€ billions)

Annex 3. FDI data

Figure 3.1. EU FDI stock as a share of national GDP, Western Balkans

Figure 3.2. EU FDI stock as a share of national GDP, EaP

Source: Bruegel based on Eurostat, World Bank and OECD.

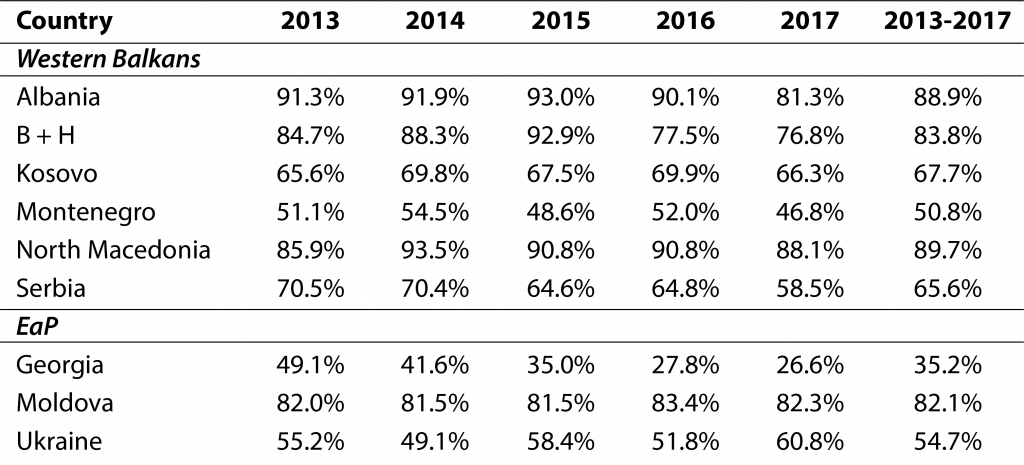

Reporting of FDI data must acknowledge that FDI statistics often mask the true origin of the investment in question, a phenomenon that is exacerbated in the case of the EU given the prominence of certain member states in global tax avoidance (Darvas et al 2023). Damgaard et al (2019) built a dataset for 2013-2017 that estimated FDI by what they term the “ultimate investor economy” (UIE). Over this period, the simple average for the WBs of FDI with the EU as UIE was 45 percent, higher than that of the EaP countries, but lower than the level of trade integration at the same time (the simple average for the EU as a share of total exports for the same period was 59 percent, Table 3.1). An average of 74 percent of the FDI reported as being from the EU across the WB countries actually had the EU as UIE, ranging from 90 percent in North Macedonia to just 50 percent in Montenegro (Table 3.2)

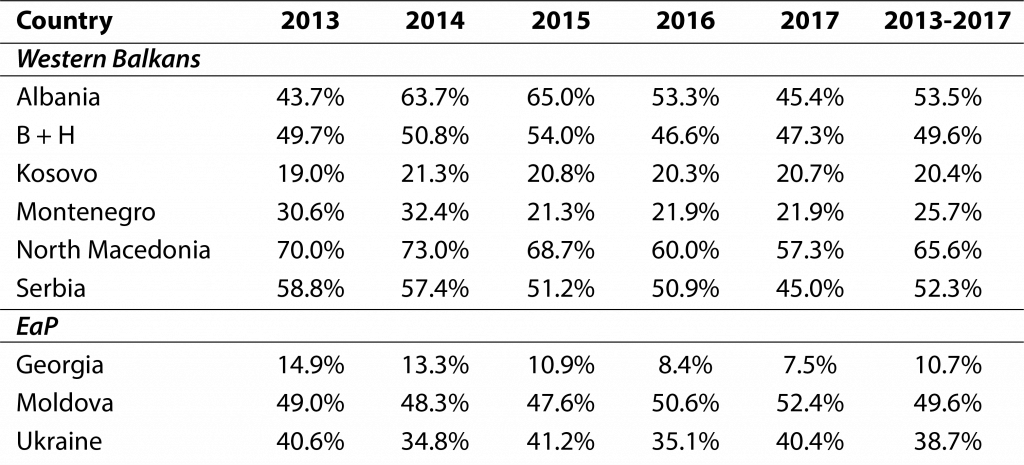

Table 3.1. Share of FDI with the EU as the ultimate investor economy in total reported FDI stock into the WB and EAP countries

Source: Bruegel based on Damgaard et al (2019) and Darvas et al (2023).

Table 3.2. FDI stock with the EU as the ultimate investor economy as a share of the reported EU FDI stock in each country

Source: Bruegel based on Damgaard et al (2019) and Darvas et al (2023).

Annex 4. Logistics and trade-related infrastructure for EaP

Source: Bruegel based on World Bank Logistical Performance Index.

Annex 5. Non-tariff barriers

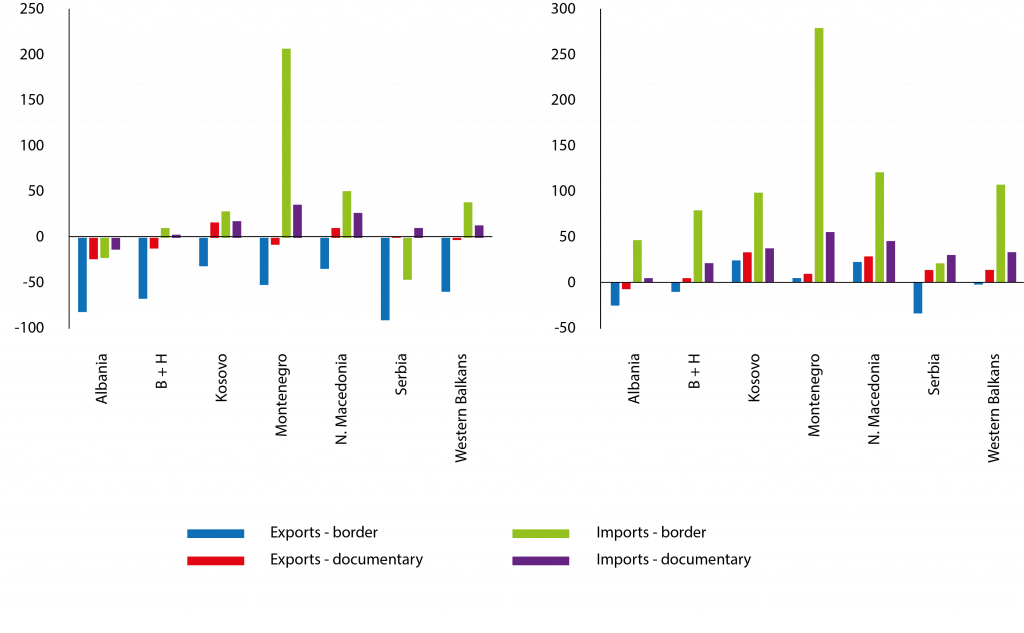

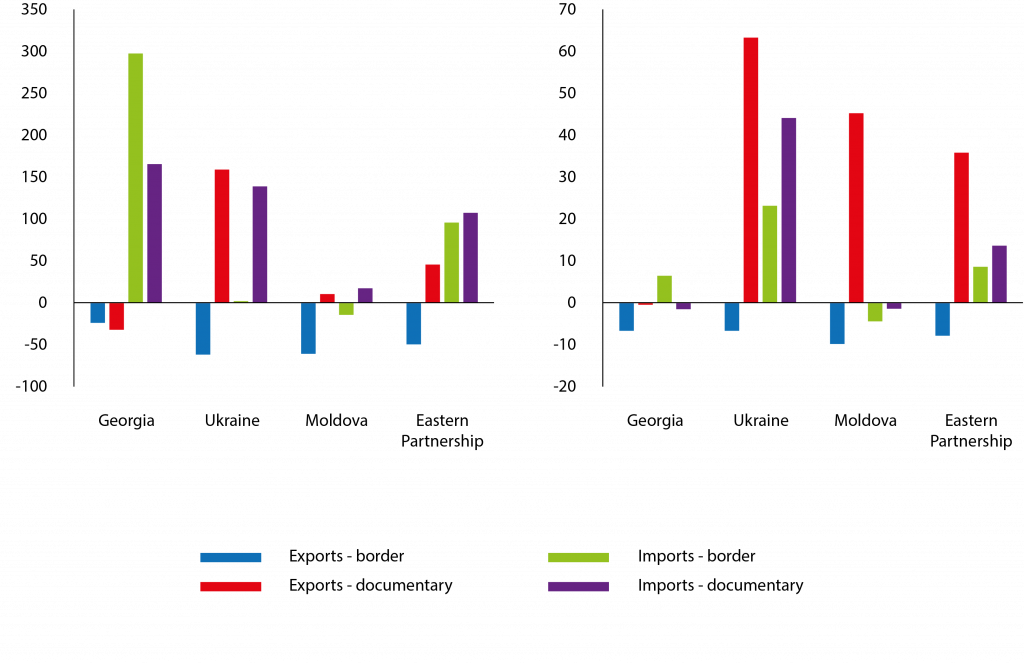

Figure 5.1. Difference in compliance costs of international trade between the Western Balkans and OECD high income countries (left) and the EU (right), $

Figure 5.2. Difference in time compliance of international trade between the Western Balkans and OECD high-income countries (left) and the EU (right), hours

Note: WBs refers to a simple average of the six WB countries. EU refers to the simple average of the EU27 countries.

Source: The World Bank ‘Trading across Borders’.

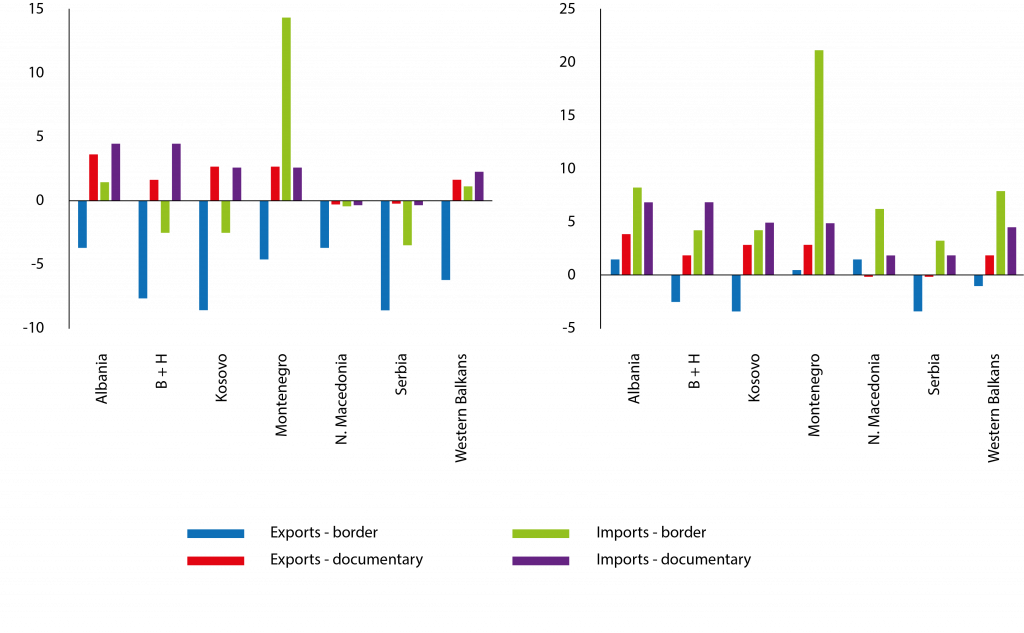

Figure 5.3. Difference in compliance costs of international trade between the EaP and OECD high-income countries in $ (left) and hours (right)

Note: WBs refers to a simple average of the six WB countries. EU refers to the simple average of the EU27 countries.

Source: The World Bank ‘Trading across Borders’.