The EU’s digital deregulation push

Mario Mariniello is a Non-Resident Fellow at Bruegel, specialising in digital and competition policy

Executive summary

To boost the European Union’s digital economy, the European Commission is seeking to reduce the burden of its digital rulebook. However, the Commission’s deregulatory strategy lacks a rigorous, evidence-based analysis of the expected effects entailed by proposed burden reductions, is insufficiently transparent and accountable in relation to potential distributive trade-offs and is overly focused on a narrow geopolitical goal of ‘catching up’ with the United States, which may neglect Europe’s distinct social and institutional priorities.

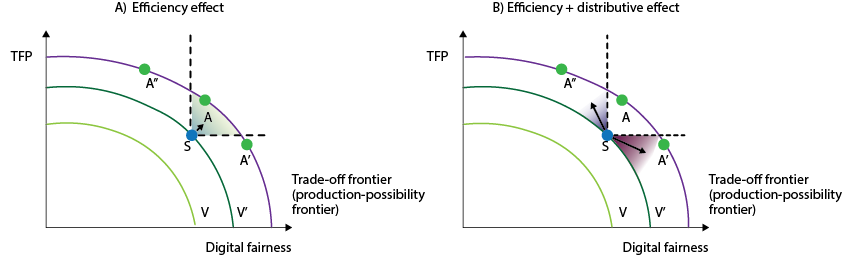

This paper introduces a framework to analyse these issues. It distinguishes between efficiency effects that enhance total societal value, and distributive effects which determine how value is shared within society. The framework explains how total factor productivity (a proxy for competitiveness) may have a complementary and a substitutive relationship with digital regulatory protection.

The Commission’s deregulatory initiatives may entail both efficiency and distributive effects, but that the Commission typically only acknowledges the former. This misrepresentation leads to unrealistic goals, such as EU companies matching the same level of data use as US companies without compromising European privacy standards.

Digital regulation can be designed to generate value and can distribute that value in accordance with the goals the Commission intends to pursue. A distinction should be introduced between ‘mitigating’ distributive effects, in which the proposed initiatives shift the distribution of value among players without fundamentally altering business models, and ‘steering’ distributive effects, in which proposed initiatives may encourage the development of alternative approaches to technological development.

In pursuing a deregulatory strategy, the Commission should be more transparent about its aims. The Commission should ground reforms in robust impact analysis, without a preconceived goal in terms of the desired amount of reduction in regulatory burden. It should also clearly identify the end goals while detailing potential trade-offs between them, and adopt measurable indicators for efficiency, mitigating distributive effects and steering distributive effects, in order to assess the potential effectiveness of its initiatives and to understand their actual impacts.

1 Introduction: The European Commission’s deregulatory strategy

On a number of indicators, European Union technological markets are trailing the United States, particularly in the development of artificial intelligence. In 2024, for example, only four of the world’s top 50 technological companies were European.

Also in 2024, European AI startups raised $12.8 billion, compared to $80.8 billion raised by their US-based counterparts1. The US ranks first in ‘Global AI Vibrancy’, a composite index developed by the Stanford Institute for Human-Centred AI (SIHC)2. The top EU country according to this index, France, ranks sixth, scoring 22.5 compared to the US’s 70.

The EU’s lagging performance is seen as worrying because thriving technological markets are considered crucial for future prosperity. Digital technologies play an infrastructural role and increasingly support the production and delivery of public goods, including public services, education, environmental policies and military security (McMillan and Varga 2022). They can significantly boost productivity (Brynjolfsson et al 2025). When used effectively, they may foster inclusivity (UNCTAD 2019).

The EU’s priorities for the digital economy have typically been framed in regulatory terms. The EU has come to be perceived as a ‘referee’ of digital markets, rather than a successful, active player3. A substantial number of EU regulations directly applicable to digital markets have been introduced.

Among the most important are the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR, Regulation (EU) 2016/679), the Digital Markets Act (DMA, Regulation (EU) 2022/1925), the Digital Services Act (Regulation (EU) 2022/2065), the Data Act (Regulation (EU) 2023/2854) and the Artificial Intelligence Act (AI Act, Regulation (EU) 2024/1689) but the overall list is much longer (Bruegel Dataset 2023).

The EU digital rulebook is consistent with a traditionally risk-averse regulatory approach enshrined in the EU Treaty4. EU digital laws are based on a precautionary approach, imposing limitations on companies ex ante, protecting public interests and preventing possible irreversible harm before it emerges (Draghi 2024). By contrast, in other jurisdictions – most notably the US – regulators tend to intervene only after evidence of harm emerges: a regulatory approach generally considered more innovation-friendly, as companies face fewer regulatory hurdles when launching new products or services5.

The persistent question for the EU therefore is whether its digital rulebook contributes to the technological gap between the EU and comparable economies? If so, should a deregulatory agenda be pursued to close that gap? The European Commission appears to believe the answer to both questions is ‘yes’ and is pursuing an approach that involves a structural recalibration of focus from regulation to competitiveness. In other words, it is primarily preoccupied with fostering development and growth of digital technologies, rather than protecting against potential harm.

The Commission’s strategy to reduce the EU’s digital regulatory burden entails plans to facilitate companies’ compliance with existing rules, making compliance less costly. It also includes policies with potentially substantial implications, such as easing regulatory reporting requirements for companies6.

The Commission is grouping such measures into so-called ‘Omnibus’ packages. An ‘Omnibus IV’ proposal in May 2025 was intended to ease GDPR compliance for smaller companies7. A ‘Digital Omnibus’ proposal, published on 19 November 20258, meanwhile, seeks to boost AI development by broadening access to data for companies, a vital issue for AI training and operation.

For example, it would expand the definition of ‘non-personal’ data, putting it beyond the scope of personal data protection. This might be done for pseudonymised data, from which the original data subject supposedly cannot be reidentified by the data processor – though another processor might be able to do so (Henriksen-Bulmer and Jeary 2016). This would create substantial new risks for data subjects.

The deregulatory strategy may also manifest passively, with the Commission choosing to refrain from acting, or abandoning or delaying previously planned proposals. For example, the EU has considered supplementing the AI Act to protect workers from potential misuse of AI in the workplace, but has not yet done so, despite prodding from the European Parliament (2025). In February 2025, the Commission withdrew a proposal to regulate standard-essential patents, despite it having already been approved by the European Parliament9.

Finally, the strategy also involves implementation delays. There have been many requests for a lengthening of the AI Act’s tight compliance timeline10. Among other things, the AI Act requires European standardisation organisations to develop standards to help providers and deployers of high-risk AI systems demonstrate compliance. These standards have yet to be developed, and in the November 2025 Digital Omnibus the Commission laid the ground to postpone the enforcement of the obligations from August 2026 to December 202711.

The Commission’s initiative may have substantive implications and we therefore term it ‘deregulatory’, rather than the Commission’s preferred term of ‘simplification’ (European Commission 2025a). We use the term ‘deregulatory’ to describe any action to reduce the burden of EU digital regulation, regardless of whether it involves lowering regulatory standards or is limited to cutting compliance costs without reducing protection. The term ‘simplification’ can be misleading, implying that the strategy will have no substantive implications.

In fact, the Commission’s digital deregulatory strategy has three main shortcomings:

1 .The deregulatory process lacks solid evidence. The Omnibus proposals have not been supported by impact assessments (IA) and have not gone through the structured ex-ante processes normally applied to evaluate the potential economic, social and environmental effects of the Commission’s initiatives. The Commission argues that IAs could not be conducted because it would take too long, while the demand for deregulation is urgent (European Ombudsman, 2024)12. However, IAs could, for example, recommend that reporting obligations cannot be further reduced, because this might have significant social or environmental repercussions.

2. The process lacks transparency. The lack of empirical evidence makes it difficult to assess whether the Commission’s strategy can effectively reduce regulatory burdens for companies. Most importantly, it hampers understanding of whether the strategy might make certain constituencies worse off, because of the proposed changes or because of regulatory inaction. This results in diminished accountability, as the Commission fails to assume responsibility for the distributive choices it implicitly asks EU legislators to make.

3. The entire digital deregulatory strategy hinges on a presumed end goal of ‘catching up’ with the US and reclaiming lost ground compared to its global competitors (as expressed in Draghi 2024). The urgency of the deregulatory strategy is justified by the technological gap between the EU and the US in terms of, for example, investment in digital infrastructure, such as data centres, funding of AI companies and adoption of digital technologies by traditional industries. The goal itself is not problematic: there is a compelling need to keep pace with the technological frontrunners and to increase the competitiveness of the European economy. However, it is risky to direct the entire strategy solely towards that specific objective, for two reasons:

First, comparing technological markets in the EU and the US is analytically unsound, for instance, because the two systems protect personal rights differently, and it is therefore obvious that markets perform differently.

Second, focusing mainly on imitating US investment strategies risks missing an opportunity to develop alternative approaches to technological development. For example, the Commission might be more concerned with the amount of AI innovation produced or adopted, rather than with which kinds of innovation gain traction in Europe. Minimising systemic differences with the US, moreover, could be hazardous by making EU technological markets more vulnerable to systemic shocks (such as the potential bursting of an AI bubble). This does not mean that the EU should not attempt to boost competitiveness, including by learning from the US. Rather, this should not be the EU’s only strategic goal.

This paper sets out a simple analytical framework to explain why these three problems risk undermining the Commission’s overarching digital goals. To address the problems, the Commission should be clear about its goals and should be more transparent on the potential effects of its regulatory and deregulatory initiatives.

The discussion in this paper, however, should not lead to the conclusion that regulation or deregulation can play a pivotal role in ensuring success in the digital economy. Quite the contrary: the roots of Europe’s problems are deep and EU regulation is only one potential contributor – and probably not the most important13. Regulation is also only one tool that policymakers must pursue to achieve public goals. It should be considered a complement rather than a substitute for industrial policy.

To analyse the effects of regulation alone, an assumption must thus be made that investing economic or political resources in changing the regulatory framework does not imply crowding out other policy instruments (which would be the case, for example, if significant political capital is invested in adopting an Omnibus proposal, reducing the chances of adopting a new subsidy scheme). This assumption is significant but necessary to evaluate the Commission’s deregulatory strategy on a standalone basis.

The next section explains the theoretical foundation of the framework proposed in this Policy Brief14. Section 3 analyses the scope for efficiency improvements to the EU digital rulebook. Section 4 discusses the distributive choices entailed by regulation. Recommendations are set out in section 5.

The entire EU digital deregulatory strategy hinges on a presumed goal of ‘catching up’ with the US

2 A model for efficiency and distribution in EU digital regulation

Regulatory changes can have two types of effects: efficiency effects and distributive effects15. Efficiency effects increase the economic value created, while distributive effects determine how that value is allocated within society16. Differentiating between them is often challenging, since a regulatory norm can produce both kinds of effects.

For example, a regulation designed to encourage market competition may have efficiency effects (as competition boosts productivity and innovation, while also reducing the risk of abusive conduct that may harm consumers) and distributive effects (by shifting value from sellers to buyers). The efficiency and distributive effects triggered by competition are highly relevant for digital markets, which tend to have a structural tendency towards concentration17.

The dynamics underpinning efficiency and distributive effects can be more easily understood through a simple economic model. Consider an economy – the EU – with an administration – the European Commission – that aims to maximise its citizens’ prosperity. It does so by producing two sets of public goods18:

The first relates to competitiveness, to how productive the EU economy is. This can be measured by total factor productivity (TFP), the part of economic growth not explained by increases in labour or capital (TFP thus depends on technological innovation, development and adoption). TFP can be considered a public good because a higher TFP means higher average incomes and tax revenues. It is associated with higher levels of prosperity, from which citizens cannot be excluded (for example, TFP is positively correlated with average wages).

The second set of public goods relates to digital fairness (DF), an umbrella term encompassing the security, safety, resilience and trustworthiness of the EU digital economy. DF includes privacy protection, online safety, cybersecurity, consumer protection, digital inclusion and AI ethical standards. DF is a public good because everyone benefits from reducing the average risk of harm when dealing with digital technologies. DF can be interpreted to include also strategic autonomy, or the EU’s ability to develop, adopt and regulate digital technologies independently, without relying excessively on foreign countries’ supply chains.

In the model, the Commission can deploy only one production factor: regulation19. Depending on how regulation is designed, it results in varying levels of TFP and DF in the economy (for example, a regulation designed to reduce barriers to entry and boost competition can produce more TFP and DF).

From a regulatory perspective, TFP and DF can be complementary but also substitutes: regulatory design may sometimes increase both TFP and DF. However, there can also be a trade-off, with one of the two indicators increasing and the other decreasing.

To illustrate the effects, consider privacy protection. Data privacy may increase overall productivity. For example, it may address market inefficiencies, increase consumer trust and expand and stabilise market demand, particularly in the long term. Lefouili et al (2024) showed that, when a sufficiently large proportion of the population is privacy-conscious, privacy regulation may increase demand among users to such an extent that a company’s incentive to innovate and generate additional revenue is enhanced (see also Choi et al 2019; Acemoglu et al 2021; Niebel 2021; Blind et al 2024; Adepeju et al 2025).

However, there is also significant evidence that privacy constraints can reduce corporate profitability by limiting their ability to tap into data (eg. Goldfarb and Tucker 2011; Campbell et al 2015; Jia et al 2021; Frey and Presidente 2024). For example, a rule that forces companies not to use personal data without consent, if binding, necessarily implies a suboptimal choice for the company.

Other examples of such constraints include rules on consumer protection, online safety, digital inclusion, AI ethics and cybersecurity. In all these examples, a case can be made for a potential negative relationship with competitiveness20. There may also be a significant trade-off between competitiveness and strategic autonomy (Meyers 2025).

For example, Lysne et al (2019) found that banning the use of Huawei telecoms equipment for security reasons increased 5G rollout costs significantly. Thus, while the relationship between TFP and DF is not linear, for the purposes of the model, it is sufficient that they can be negatively correlated, even if only occasionally21.

Finally, the model assumes that EU citizens have variable preferences related to TFP and DF and want them in differing combinations. A digital company’s shareholders may attach relatively more value to TFP than members of a minority population group at higher risk of online discrimination, for example. Thus, within this model, efficiency effects arise whenever, in the wake of Commission regulatory or deregulatory action, the sum of TFP and DF increases, expanding total economic value. Conversely, for distributive effects to arise, it is sufficient that one of the two variables decreases.

Figure 1 represents the model graphically using a typical economic illustration of a production trade-off under resource scarcity. The slopes represent different levels of prosperity (V = economic value). The EU economy is currently at the starting point – S in Figure 1. Through value-enhancing regulation, it can move upwards and/or outwards, until it reaches the maximum value that can be produced with the available resources. This maximum is represented by the purple line, known as the production-possibility frontier.

Figure 1. Regulation and the production-possibility frontier

Source: Bruegel.

Figure 1 Panel A shows how the Commission typically presents regulatory initiatives. The Commission might argue that GDPR streamlining proposals will serve a public goal (for example, simplifying compliance and increasing competitiveness) without compromising privacy protection (eg. European Commission 2025d).

In the November 2025 Digital Omnibus, the Commission has proposed controversial measures that may, for example, allow companies to use pseudonymised data that would have previously considered as personal data and thus subject to stricter protection. This could generate new risks of discriminatory conduct by data controllers22.

Nonetheless, in the introduction to the Digital Omnibus, the Commission states: “the measures are calibrated to preserve the same standard for protections of fundamental rights” (European Commission 2025c).

Conversely, the Commission might assert that introducing stricter privacy rules will not harm competitiveness. For example, the impact assessment accompanying the GDPR proposal more than a decade ago claimed that the new regulatory framework would support innovation and growth in the digital single market (European Commission 2012).

None of the impact assessments accompanying a sample of 14 significant Commission digital regulatory initiatives since 2019 mentions possible negative effects on growth (TFP in the model), instead often anticipating significant net positive effects on competitiveness and innovation23. In other words, the Commission generally expects its proposals to encourage the EU economy to shift from S to another equilibrium within the area highlighted in green (for example, to point A; Figure 1, Panel A).

But reality is harsher. Even if regulatory initiatives increase economic value, they are likely to also have significant distributive effects. Figure 1 Panel B shows how the economy might move to other equilibria (to A’, where TFP is lower – the purple area – or to A’’, where DF is lower – the blue area – for example). Distributive effects should always be disentangled from efficiency effects and, if possible, quantified.

For example, Aridor et al (2021) found that an opt-in requirement in the GDPR for online tracking led to a 12.5 percent reduction in consumers using a major online travel intermediary, lowering advertising revenues (this loss was partly offset by the valuable information that those customers who consented to share their data conveyed to the intermediary).

Similarly, the AI Act obliges providers of high-risk AI systems to ensure that datasets are relevant, representative and free of bias, and to implement procedures to detect, prevent and mitigate discriminatory effects. Von Zahn et al (2022) demonstrated that removing gender bias from AI prediction models in e-commerce led to an 8 percent to 10 percent increase in financial costs for model promotors. That is the cost requiring fairness in AI: if companies cannot use gender to predict consumer behaviour, they lose a tool to increase profits (Von Zahn et al 2022).

These exercises focused solely on distributive effects: lost profits induced by the AI Act or the GDPR are not the result of inefficiencies in the design or enforcement of the regulatory framework. This is important because many studies that seek to quantify the effects of regulation on productivity are based on comparisons of average productivity in the market with and without regulation.

In such comparisons, it is often unclear whether the productivity effects result from flawed regulatory design (which can be corrected) or to deliberate choices by the legislator, which pursues multiple, conflicting goals.

Despite strong evidence of distributive trade-offs, however, the narrative that regulatory or deregulatory actions can pursue incompatible objectives remains firmly embedded in the public debate. For example, Mario Draghi, the former Italian prime minister and author of a major report on competitiveness intended to guide the European Commission, has said that for European companies, “one of the clearest demands is for a radical simplification of GDPR,” which has “raised the cost of data by about 20 percent for EU firms compared with US peers” (Draghi 2025).

The GDPR, however, increases data costs by design. It includes the principle of data minimisation, requiring data controllers to restrict data processing to what is necessary. US companies that are not subject to the GDPR when operating outside the EU might instead collect and process data without a clearly defined purpose. It thus makes little sense to compare data use in the EU and US and blame lower EU data use on the GDPR’s supposed inefficiencies.

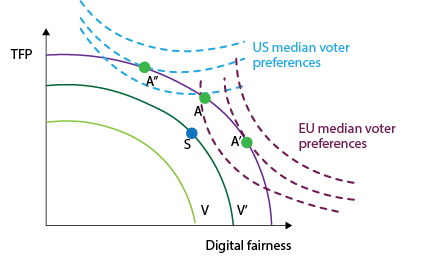

Figure 2 illustrates these dynamics. The blue lines are ‘indifference curves’, or different combinations of TFP and DF that bring the same value to the individual, for US and EU median voters. The US median voter is assumed to have flatter indifference curves than the EU median voter, meaning she values TFP over DF relatively more than her EU counterpart24.

Survey evidence supports this assumption. Germans, for example, tend to attribute a higher value to privacy when using digital technologies than Americans (Prince and Wallsten 2022; Despres et al 2024). Bellman et al (2004) demonstrated that cultural preferences influence regulatory approaches, with US internet users generally less concerned than Europeans about online safety. This provides a possible explanation for the EU’s precautionary approach and the US’s risk-based regulatory approach.

Since the European Commission aims to maximise its citizens’ prosperity, it should seek through regulation to reach the point at which the EU median voter’s preferences coincide with the trade-off frontier (Figure 2, point A’). At this point, TFP is inevitably lower than at point A’’, which would be the equilibrium if the EU median voter had the same preferences as the US median voter.

Figure 2. Differences in citizens’ preferences entail different equilibria

Source: Bruegel.

The model shows that failing to distinguish efficiency from distributive effects results entails overlooking the fact that some differences between the economic performances of the EU and the US are structural and cannot be eliminated through better regulatory design. Digital fairness may imply a TFP cost. That cost should be acknowledged. The Commission should dispel the misconception in its deregulatory agenda that, simply by streamlining the EU digital rulebook, protection and competitiveness can always be maximised simultaneously.

3 Efficiency gains: increasing value with EU digital regulation and deregulation

EU digital regulation creates value primarily by expanding digital markets from national to European level. It does this establishing common supranational rules that override national approaches: it fosters the digital single market (DSM). Since digital business models greatly benefit from economies of scale, the value created in a fully developed DSM would exceed the total of the values generated within each EU country, if considered separately. A completed DSM would reduce uncertainty for businesses and boost competition25.

Therefore, when EU regulation tackles issues such as data use that would otherwise be regulated at national level, it prevents fragmentation and thereby creates value gains. For example, the GDPR and another law, the Regulation for the Free Flow of Non-Personal Data (Regulation (EU) 2018/1807), were designed, taken together, to facilitate the seamless transfer of data across the EU, overcoming national barriers and expanding the data market from the national to the EU level, with notable efficiency benefits (European Commission 2025b)26.

The DSM remains incomplete, however. Regulations that appear effective on paper often fail to deliver in practice. The GDPR is not enforced uniformly across the EU as originally intended, for example (Gentile and Lynskey 2022). It is this inconsistency that is likely the main reason for the EU’s competitive disadvantage, and lack of digital champions, compared to the less-fragmented US and China (Letta 2024; Draghi 2024).

The EU’s fragmented market hinders businesses from starting up, securing funding and expanding. Rather than being a drag on competitiveness, EU regulation, if well designed, has the potential to foster, rather than impede, the emergence of European champions.

But regulation is often not well-designed and for that reason can impose significant compliance costs on companies. Annual compliance costs related to the GDPR have been estimated up to €500,000 for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and up to €10 million for large organisations (Draghi 2024). Most importantly, regulation can create unwarranted distortions in technological markets. Whenever regulators constrain companies’ behaviour, they interfere with natural market dynamics, potentially resulting in inefficient outcomes.

For instance, regulators may reduce competition by (intentionally or inadvertently) erecting barriers to market entry. Alternatively, they may favour companies that do not deserve to be advantaged because they are less efficient than their competitors.

The GDPR, for example, introduced a mandatory data-management process for companies that handle large or highly sensitive datasets. These processes entail high fixed costs and thus larger firms have a comparative advantage, as the cost of GDPR compliance is relatively lower for them than for SMEs, because of economies of scale. Peukert et al (2022) provide evidence that web technology service markets have become more concentrated since the introduction of the GDPR. One aim of the Commission’s May 2025 Omnibus IV proposal (European Commission 2025d) is to address this issue.

The risk of distortion can never be entirely eliminated when regulation is introduced. However, it can be minimised by ensuring that regulations are linked closely to the market failure they address. In other words, regulation should not target issues that the market is expected to resolve within a reasonable timeframe. Often, instead, the EU regulates where not strictly needed.

For example, the AI Act obliges that high-risk AI systems with the greatest potential to cause harm to be accurate, robust and cyber-secure. Competition in AI system design is intense (HAI, 2025), and accuracy is one of the principal parameters on which developers compete.

Therefore, one should expect that the market will incentivise and reward more accurate AI systems. The need for accuracy requirements in regulation is thus not obvious.

The potential for value gains through both regulatory and deregulatory digital measures in the EU thus seems significant. The GDPR, for instance, could be improved by streamlining enforcement, ensuring it is more consistent and effective across the single market and emphasising higher-risk use cases. Reporting processes could be streamlined to reduce duplication with overlapping obligations under other regulations, such as the Digital Services Act or the AI Act27.

Additionally, the GDPR could incorporate greater automation in processing users’ consent for their personal data and could standardise consent requirements, easing compliance for low-risk data controllers. The November 2025 Digital Omnibus proposal requires automated privacy signals from browsers to overcome cookie consent fatigue, and this is no doubt a good step towards a more efficient regulatory framework.

4 The distributive effects of regulation

Fixing market failures (such as correcting the lack of market competition) entails both efficiency and distributive effects. Regulation, however, can also be designed primarily to have distributive effects (ie. to move along the efficiency frontier in Figure 1), without targeting a specific market failure. This is often true in the digital economy for three reasons.

First, correcting market failures takes time and is often outpaced by technological progress. The Digital Markets Act, for example, contains norms to enhance competition structurally, such as reducing the costs of switching between large online platforms (Article 6(6) DMA), and also fairness measures, such as preventing large platforms from exploiting non-public commercial data obtained from their business users in order to compete against those users (Article 6(2) DMA)28.

EU lawmakers assumed rightly that, even if the DMA Article 6(6) increases competition in digital markets by correcting the market failure arising from low levels of competition, ultimately reducing the likelihood of abuse, it will take a considerable amount of time to see results29. Therefore, Article 6(2) was also needed to prevent exploitation directly.

Second, perfectly functioning markets exist only in theory, and given the highly dynamic nature of digital markets, it would be naive to expect regulation to resolve all potential market failures indefinitely. The third reason is that even if markets did not fail and the economy was permanently at the efficiency frontier, it would not necessarily mean a distribution of value considered fair by society’s members, even if those members operate and manifest their preferences via the economy’s markets30.

Consider, for example, economic discrimination, or the practice of treating comparable economic actors differently to extract value from them. The data economy is based on the idea that users’ information can be used to generate value. The more producers know about their customers, the better they can tailor their offerings.

Online e-commerce platforms, for instance, can set higher prices for buyers who are more willing to pay (Borreau and de Streel 2018). On an aggregate level, this might be efficient because the supplier (the e-commerce platform) sells to everyone and maximises sales (in other words, price discrimination can get you closer to the efficiency frontier).

However, most of that overall value is captured by the discriminating platform. In the extreme case of first-degree price discrimination31, the economy may be at the efficiency frontier but buyers are left only with the value of their consumption. They gain no ‘surplus’, ie. the potential difference between what they are willing to pay and what they actually pay. Since all pay different prices, buyers might feel they are being treated unfairly.

The EU digital regulator opposes discrimination, as demonstrated by several explicit regulatory provisions. For example, Article 10(2) of the AI Act requires data-governance measures to mitigate discrimination by high-risk AI systems. Article 26(3) of the Digital Services Act forbids the use of sensitive information, such as sexual orientation or political beliefs, for targeted advertising.

Such provisions reflect a distributive-oriented choice by the regulator because, on pure efficiency grounds, discrimination could in theory be justified32. Discrimination might expand the economic value produced in the economy.

4.1 Mitigating vs. steering distributive effects

Regulation can have different types of distributive effects. In the analytical framework outlined in this paper, mitigating distributive effects, in which proposed laws shift the distribution of value among players without fundamentally altering business models, should be distinguished from steering distributive effects, in which proposed laws may encourage the development of alternative approaches to technological development.

The DMA contains an example of a potential mitigating distributive effect, as it prohibits large platforms from favouring their own services (prohibition of self-preferencing, Article 6(5)). This principle does not aim to change the business model, but rather to prevent abuse. However, it has distributive effects because it shifts value from platforms to their rivals, and this is not necessarily value-enhancing. In fact, self-preferencing may be pro-competitive, increasing consumer welfare (Katz 2024).

The GDPR, meanwhile, generates steering distributive effects, as it pushes companies to develop more privacy-friendly businesses and to adopt technologies that minimise data use (GDPR Article 25). Martin et al (2019) showed that the GDPR steers innovation in startups in data-intensive sectors towards privacy-preserving software.

Steering distributive effects are particularly important for the digital economy because they enable regulation to influence systemic choices. Through steering distributive effects, regulation can establish the foundation for alternative technological development paths, rather than those dominated by the US or China.

The need for systemic choices is urgent given the nature of digital technologies, which are increasingly deeply embedded in EU society and the economy. AI is progressively becoming the ‘infrastructure of infrastructures’33.

However, systemic choices are only feasible at an early stage of development. Once the economy has adapted to a new technological system, it can be extremely difficult to change it through regulation. David (1985) and Arthur (1989), for example, described this as technological path dependency: early coordination on a technology (cars, VHS) commits society to a specific trajectory that is hard to change.

Furthermore, significant risks are associated with the implicit decision to match the EU’s digital deregulatory agenda with the US. First, it is unlikely that the US’s technological lead can be matched, given its strong first-mover advantage. This is evident in how large US AI firms can utilise extensive data and computing facilities and thus benefit from substantial economies of scale (Krakowski et al 2023).

Second, as shown in the model described in section 2, bridging the EU-US divide would inevitably involve compromising the EU’s approach to technology, which is grounded in applying regulation to promote a human-centric digital economy (European Commission 2022). Aping the US would diminish the EU’s comparative advantage. By lowering safety or security standards, the EU could, for example, become less attractive to foreign talent.

Third, steering distributive effects can be beneficial for strategic autonomy goals, as they can support the development of technologies for which foreign powers lack a comparative advantage. The more these technologies become widespread, the greater the EU’s bargaining power. For instance, the principle of privacy by design enshrined in the GDPR might favour data-processing technologies that handle data closer to data subjects34.

Adoption of such technologies has been underwhelming so far but with support from complementary industrial policies, they could become more significant, exerting competitive pressure on the cloud market, enabling local, sovereignty-preserving alternatives that make centralised services less necessary.

Finally, by focusing its efforts on joining the AI gold rush, the EU maximises its exposure to potential systemic risks affecting the AI system. AI may be nearing an investment bubble. If the bubble bursts, the economic impact would be less severe if the EU had diversified its technological investments and prioritised a long-term perspective, taking into account AI’s ethical, societal and environmental impacts (Floridi 2024).

Regulation alone cannot compel systemic choices; however, it can support them. For instance, regulation can offer a strategic edge in technologies that may follow AI as the next major trend, such as quantum technologies. It could establish interoperability standards, design faster assessments of safety, security and regulatory compliance of quantum systems, or introduce public procurement rules, such as cybersecurity requirements, that promote the adoption of quantum technologies. By boosting demand for quantum, regulation would assist in directing investment towards it.

Regulation can likewise potentially prompt radical changes in digital business models or directly prohibit certain harmful uses. The Digital Services Act, for instance, could be enforced in a manner that brings about fundamental changes to social network business models, reducing addiction or doomscrolling by requiring adjustments to recommendation algorithms and engagement-driven design features.

Labour-market regulation could steer technological progress by boosting workers’ bargaining power and shaping incentives so that innovation focuses on augmenting labour rather than just replacing it; this implies banning or heavily restricting the use of monitoring or surveillance AI-enabled applications (Acemoglu and Johnson 2023).

5 Recommendations for a transparent and effective digital deregulatory strategy

The European Commission’s deregulatory digital strategy: 1) lacks an evidence base; 2) lacks transparency, and the Commission is not accountable for the distributional choices it makes; 3) is implicitly aimed at the unrealistic goal of catching up with the US while maintaining the EU’s level of protection from harm caused by digital technologies (section 1).

The Commission should not ignore the potential for distributive effects, assuming that its deregulatory strategy will only have efficiency effects. The Commission may use regulation or deregulation to pilot the economy to generate more value (section 3) and to distribute that value according to the goals it intends to pursue (section 4). But to be effective, it must acknowledge trade-offs and be transparent about the cost its initiatives entail.

The Commission’s deregulatory strategy should therefore:

1. Design an effective methodology to support any future regulatory or deregulatory initiatives with solid economic evidence. The claim that the urgency to take action prevents the carrying out of impact assessments overlooks the potential for substantial distributive effects35.

2. Relatedly, the Commission’s strategy should not specify from the outset fixed goals for the level of regulatory burden it aims to cut. The strategy’s efficiency target must be to maximise the value generated by the EU digital economy. Reducing the compliance burden is a means to achieve that aim but not a goal in itself.

3. Whenever a full impact assessment is not feasible, the Commission should still accompany initiatives with broad analyses of the potential effects. Analyses need not be detailed, but must be thorough and sound, highlighting all relevant dynamics, at least at the theoretical level36. The public goods involved should be identified clearly and whether they are in a complementary or substitutive relationship should be explained.

For example, if the Commission proposes to exempt AI companies from the ban on using sensitive personal data to train algorithms, it should clearly outline all academic literature indicating that using sensitive data for AI training may jeopardise human rights. Similarly, the Commission must establish the theoretical basis that supports the expected efficiency effects.

4. The Commission should state clearly the ultimate purpose of its deregulatory strategy. If the aim is solely to narrow the gap between EU and US tech markets, it should state this explicitly and outline the kinds of distributive decisions that will be needed to achieve that aim.

Conversely, if the goal is to help bridge the EU-US gap while also allowing for different visions of technological development to emerge, it should recognise that, in some areas, the EU-US gap might never be fully closed. For example, access to data in Europe will always be more costly (and, therefore, lower) than in the US, if the EU maintains higher privacy standards.

5. Finally, the Commission should establish metrics to assess the potential effectiveness of its initiatives ex ante and to validate them ex post. In this respect, technology can also be considered an enabler, rather than just the target of Commission proposals: large language models can speed up data analysis and improve its quality, and it is increasingly hard to justify regulatory proposals that lack quantitative backing. The Commission should propose:

Indicators to measure efficiency effects, such as: total reduction of compliance costs; lower exposure of personal data to potential abuse; increase in investment in technological infrastructure; increase in private and public adoption of digital services; reduction of cybersecurity risk; increase in online safety; quantitative increases in technological innovation.

Indicators to measure mitigating distributive effects, such as: changes in the balance of expected revenues between different kinds of market players (of different sizes or operating in different sectors); loss of established rents in relation to the creation of new safeguards from online harm; gains of new rents by specific market players in relation to loss of established consumer protections.

Indicators to measure steering distributive effects, such as: relative changes in the balance of different kinds of technological innovation (for example, the ratio between safety-oriented and monitoring-oriented AI-powered applications in the workplace); shifts in investment between different kinds of technologies; creation of new technological business models.

Proponents of deregulation, such as the European Commission, often assert that deregulation will cause no harm. Conversely, opponents tend to argue that boosting trust in digital technology through regulation reinforces the sustainability of tech business models. Neither claim is fully convincing, and a polarised debate may impede EU efforts to improve its regulatory framework and support the growth of European tech markets. The Commission should therefore adjust its deregulation strategy by increasing transparency about its aims and taking full responsibility for its actions.

Endnotes

1. See Statista, ‘The 100 largest companies in the world by market capitalization in 2024’, 30 May 2025, and Dealroom (2025).

2. See the Global AI Vibrancy Tool. The composite index includes metrics such as research output, investment, infrastructure and policy.

3. Guntram Wolff, ‘Europe may be the world’s AI referee, but referees don’t win’, Politico, 17 February 2020.

4. As seen in the EU approach to environmental policy; Art. 191(2) of the Treaty on Functioning of European Union.

5. This, however, is not necessarily true when also considering the qualitative aspects of innovation. See Klinke and Renn (2002), for example.

6. A move to simplify sustainable finance rules has been criticised for its potential to distort sustainable-finance markets by significantly reduce companies’ reporting; see Sylvia Merler, ‘Streamlining or hollowing out? The implications of the Omnibus package for sustainable finance’, First Glance, 3 March 2025, Bruegel.

7. European Commission, ‘Omnibus IV’, 21 May 2025.

8. See European Commission press release of 19 November 2025, ‘Simpler EU digital rules and new digital wallets to save billions for businesses and boost innovation’.

9. Francesca Micheletti and Mathieu Pollet, ‘EU’s red tape bonfire stokes tech patent rows’, Politico, 12 February 2025.

10. The AI Act is a comprehensive framework governing the development, market placement, deployment and use of AI systems within the EU. It entered into force in August 2024, but its full applicability is being phased in.

11. See European Commission press release of 16 September 2025, ‘Commission collects feedback to simplify rules on data, cybersecurity and artificial intelligence in the upcoming Digital Omnibus’. The 19 November 2025 Digital Omnibus gives the option to the Commission to decide to delay enforcement.

12. Drafting an impact assessment can take more than a year (European Commission, 2009). In relation to the Omnibus proposals, the results of impact assessments in any case may have been predetermined to some extent: Commission President Ursula von der Leyen has said that she considers necessary a reduction in reporting obligations for large corporates of at least 25 percent, and for small and medium enterprises, of at least 35 percent. See Ursula von der Leyen, ‘Mission Letter Valdis Dombrovskis, Commissioner-designate for Economy and Productivity, Commissioner-designate for Implementation and Simplification’, 17 September 2024.

13. Most of European companies’ compliance costs originate in EU countries’ national legislation. In addition, European companies do not consider regulation as the main obstacle to investment (EIB, 2024).

14. This paper draws extensively from, and expands on, Mariniello (2025).

15. This classification is broadly consistent with the mainstream economic literature on regulation. See, for example, Joskow and Rose (1989) and Baldwin et al (2011).

16. Value is an all-encompassing concept used to indicate how prosperous an economy is. It is equivalent to total welfare or total utility. It can include measurable quantities (such as domestic output) and less objectively quantifiable benefits (quality and accessibility of services).

17. Digital services, for instance, tend to benefit from scale and network externalities, which naturally lead to market concentration.

18. A public good is a good defined by two properties: non-rivalry (one person’s consumption of the good does not reduce its availability to others) and non-excludability (individuals cannot easily be excluded from benefiting once the good is provided).

19. This is a drastic simplification, of course. TFP and DF depend on many other factors, and the Commission has many different policy tools to produce them. The purpose of this model is, however, to isolate the effect of regulation. The model thus assumes that all the other factors or policy tools affecting TFP and DF are given.

20. Consumer protection increases liability risks and may deter innovation or market entry for new technologies; online safety may divert resources to moderation and compliance; digital inclusion may imply pricing constraints and reduced profitability; AI ethics limits companies in using sensitive data to optimise pricing strategies; cybersecurity increases operational costs.

21. Researchers have attempted to explain that the dichotomy regulation vs competitiveness does not necessarily hold (see, for example, Bradford 2024). However, this does not imply that such a dichotomy never holds.

22. Mario Mariniello, ‘The European Commission’s Digital Omnibus could increase risks, not growth’, First Glance, 13 November 2025, Bruegel.

23. The examined initiatives are: the Digital Services Act, Digital Markets Act, AI Act, Data Act, Cyber Resilience Act, NIS2 Directive, European Digital Identity Regulation (eIDAS 2.0), Data Governance Act, Platform Work Directive, European Health Data Space, Gigabit Infrastructure Act, Interoperable Europe Act, European Media Freedom Act and the revision of the Product Liability Directive.

24. The flatter the indifference curve, the more units of the good on the X-axis are needed to compensate for a reduction of one unit in the good on the Y-axis, for the individual to be indifferent when two bundles of goods are compared.

25. EIB (2024) found that uncertainty was considered a major obstacle to investment by 44 percent of European companies, while regulation was considered an obstacle by 32 percent.

26. The Digital Omnibus repeals Regulation (EU) 2018/1807 because it has been de facto superseded by the Data Act.

27. The Digital Services Act establishes an EU regulatory framework for online intermediaries, attempting to enhance transparency, accountability and user protection, reducing the spread of illegal and harmful content online.

28. The DMA requires online platforms with significant market power to make some of their services compatible with others. Without this regulation, competition in those markets would remain low because the major platforms benefit from large network effects, giving them a significant advantage over potential challengers. By opening markets to competition, the DMA aims to unlock their potential and encourage the creation of more value for the economy than they currently generate.

29. Increasing market competition reduces the ability of incumbent players to abuse their market power. In the extreme (and theoretical) scenario of perfect competition, no abuse is possible because no market player has the power to commit it.

30. What ‘fairness’ amounts to is a matter for political philosophy. See, for example, Rawls (2001) and Rawls (2005).

31. First-degree price discrimination occurs when a supplier has full information about its customers’ willingness to pay for its products. For an overview, see Mariniello (2022).

32. There are many reasons why discrimination can reduce or increase efficiency. It depends on the context. For an analysis, see Papandropoulos (2007).

33. Robin Berjon, ‘Infrastructure Shock’, 23 September 2024.

34. ‘Fog’ computing, for example, moves cloud capabilities closer to end devices by processing data locally within a network. ‘Edge’ computing processes data directly on or near devices, minimising latency and bandwidth use.

35. Draghi (2024) may have been the catalyst for the Commission’s strategy, but lacks granularity to justify specific regulatory design choices.

36. The 207-page European Commission Staff Working Document accompanying the November 2025 Digital Omnibus proposals dedicates just slightly more than one page to measuring the distributional impact of the proposed GDPR amendment on pseudonymised data. See European Commission (2025e), pages 54-55.

References

Acemoglu, D, A Makhdoumi, A Malekian and A Ozdaglar (2021) ‘Too Much Data: Prices and Inefficiencies in Data Markets’, American Economic Journal: Microeconomics 13(4): 1–42.

Acemoglu, D and S Johnson (2023) Power and Progress: Our Thousand-Year Struggle Over Technology and Prosperity, New York: Public Affairs.

Adepeju, AS, CA Edeze and MT Adenibuyan (2025) ‘Personalization vs. Privacy: Consumer Trust in AI-Driven Banking Marketing’, Multidisciplinary Research Journal 12(3): 45-61.

Aridor, G, Y-K Che and T Salz (2021) ‘The Effect of Privacy Regulation on the Data Industry: Empirical Evidence from GDPR’, Proceedings of the 22nd ACM Conference on Economics and Computation: 93–94.

Arthur, WB (1989) ‘Competing Technologies, Increasing Returns, and Lock-In by Historical Events’, Economic Journal 99(394): 116-131.

Baldwin, R, M Cave and M Lodge (2011) Understanding Regulation: Theory, Strategy, and Practice, Oxford University Press.

Bellman, S, EJ Johnson, SJ Kobrin and GL Lohse (2004) ‘International Differences in Information Privacy Concerns: A Global Survey of Consumers’, The Information Society 20(5): 313-324.

Blind, K, C Niebel and C Rammer (2024) ‘The Impact of the EU General Data Protection Regulation on Product Innovation in Firms’, Industry and Innovation 31(3): 311–351.

Borreau, M and A de Streel (2018) ‘The Regulation of Personalised Pricing in the Digital Era’, Note DAF/COMP/WD(2018)150, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Bradford, A (2024) ‘The False Choice Between Digital Regulation and Innovation’, Northwestern University Law Review 118(2).

Bruegel Dataset (2023) ‘A dataset on EU legislation for the digital world’, version of 6 June 2024.

Brynjolfsson, E, D Li and L Raymond (2025) ‘Generative AI at work’, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 140(2): 889-942.

Campbell, J, A Goldfarb and C. Tucker (2015) ‘Privacy Regulation and Market Structure’, Journal of Economics & Management Strategy 24(1): 47-73.

Choi, JP, D-S Jeon and B-C Kim (2019) ‘Privacy and Personal Data Collection with Information Externalities’, Journal of Public Economics 173: 113–124.

David, PA (1985) ‘Clio and the Economics of QWERTY’, American Economic Review 75(2), 332–337.

Dealroom (2025) ‘Opening moves in global AI’, AI Action Summit, Paris, February.

Despres, T, M Ayala, N Zacarias Lizola, G Sánchez Romero, S He, X Zhan … J Bernd (2024) ‘“My Best Friend’s Husband Sees and Knows Everything”: A Cross-Contextual and Cross-Country Approach to Understanding Smart Home Privacy’, Proceedings on Privacy Enhancing Technologies (PoPETs) 2024(4): 413–449.

Draghi, M (2024) The future of European competitiveness: A competitiveness strategy for Europe (Part A) and In-depth analysis and recommendations (Part B), European Commission.

Draghi, M (2025) ‘High Level Conference – One year after the Draghi report: what has been achieved, what has changed’, speech, 16 September.

European Commission (2009) ‘Impact Assessment Guidelines – Annexes’, SEC(2009) 92 final.

European Commission (2012) ‘Impact Assessment accompanying the document Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on the protection of individuals with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data (General Data Protection Regulation)’, SEC(2012) 72 final.

European Commission (2025a) ‘A Simpler and Faster Europe: Communication on implementation and simplification’, COM(2025) 47 final.

European Commission (2025b) The European Data Market Study 2024–2026: First Report on Facts and Figures.

European Commission (2025c) ‘Proposal for a Digital Omnibus’, COM(2025) 837 final.

European Commission (2025d) ‘Proposal for a Directive and a Regulation as part of the Omnibus IV – Simplification Package’, COM(2025)501 and COM(2025)502.

European Commission (2025e) ‘Staff Working Document accompanying the proposal for a Digital Omnibus and the proposal for a Digital Omnibus on AI’, SWD(2025) 836 final.

EIB (2024) EIB Investment Survey 2024: European Union Overview, European Investment Bank.

European Ombudsman (2024) ‘Decision on the European Commission’s failure to carry out an impact assessment before adopting the ‘Omnibus’ package of legislative proposals (case 1400/2024/MIG)’, Strasbourg, 11 September 2024.

European Parliament (2025) ‘Draft report with recommendations to the Commission on digitalisation, artificial intelligence and algorithmic management in the workplace – shaping the future of work’, 2025/2080(INL).

Floridi, L (2024) ‘Why the AI Hype Is Another Tech Bubble’, Philosophy & Technology, 37(4): 128.

Frey, CB and G Presidente (2024) ‘Privacy regulation and firm performance: Estimating the GDPR effect globally’, Economic Inquiry 62(3): 1074-1089.

Gentile, G and O Lynskey (2022) ‘Deficient by Design? The Transnational Enforcement of the GDPR’, International and Comparative Law Quarterly 71(4): 799-830.

Goldfarb, A and CE Tucker (2011) ‘Privacy Regulation and Online Advertising’, Management Science 57(1): 57-71.

HAI (2025) AI Index Report 2025, Stanford Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence.

Henriksen-Bulmer, J and S Jeary (2016) ‘Re-identification attacks—A systematic literature review’, International Journal of Information Management 36(6): 1184-1192.

Jia, J, GZ Jin and L Wagman (2021) ‘The Short-Run Effects of GDPR on Technology Venture Investment’, Marketing Science 40(4): 593-812.

Joskow, PL and NL Rose (1989) ‘The Effects of Economic Regulation’, in R Schmalensee and RD Willig (eds) Handbook of Industrial Organization, vol. 2, Elsevier.

Katz, ML (2024) ‘Does it matter if competition is “fair” or “on the merits”? An application to platform self-preferencing’, Review of Industrial Organization 66: 43-70.

Klinke, A and O Renn (2002) ‘A New Approach to Risk Evaluation and Management: Risk-Based, Precaution-Based, and Discourse-Based Strategies’, Risk Analysis 22(6): 1071-1094.

Krakowski, S, J Luger and S Raisch (2023) ‘Artificial intelligence and the changing sources of competitive advantage’, Strategic Management Journal 44(6): 1425-1452.

Lefouili, Y, L Madio and YL Toh (2024) ‘Privacy Regulation and Quality-Enhancing Innovation’, The Journal of Industrial Economics 72(2): 662-684.

Letta, E (2024) Much More than a Market, report to the European Council.

Lysne, O, A Elmokashfi and NN Schia (2019) ‘Critical communication infrastructures and Huawei’, TPRC47: The 47th Research Conference on Communication, Information and Internet Policy.

Mariniello, M (2022) Digital Economic Policy: The Economics of Digital Markets from a European Union Perspective, Oxford University Press.

Mariniello, M. (2025) ‘Efficiency and Distributive Goals in the EU Tech Regulatory Strategy’, Intereconomics 60(3): 141-148.

Martin, N, C Matt, C Niebel and K Blind (2019) ‘How Data Protection Regulation Affects Startup Innovation’, Information Systems Frontiers 21(6): 1307-1324.

McMillan, L and L Varga (2022) ‘A review of the use of artificial intelligence methods in infrastructure systems’, Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 114: 105161.

Meyers, Z (2025) ‘Can the EU reconcile digital sovereignty and economic competitiveness?’ CERRE Issue Paper, September, Centre on Regulation in Europe.

Niebel, C (2021) ‘The Impact of the General Data Protection Regulation on Innovation and the Global Political Economy’, Computer Law & Security Review 41: 105523.

Papandropoulos, P (2007) ‘How Should Price Discrimination Be Dealt with by Competition Authorities?’ Concurrences 3: 34-38.

Peukert, C, S Bechtold, M Batikas and T Kretschmer (2022) ‘Regulatory Spillovers and Data Governance: Evidence from the GDPR’, Marketing Science 41(4): 318-340.

Prince, JT and S Wallsten (2022) ‘How Much Is Privacy Worth Around the World and Across Platforms?’ Journal of Economics & Management Strategy 31(4): 841-861.

Rawls, J (2001) Justice as Fairness: A Restatement, Harvard University Press.

Rawls, J (2005) Political Liberalism (2nd ed.), Columbia University Press.

UNCTAD (2019) Digital Economy Report 2019: Value Creation and Capture – Implications for Developing Countries, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development.

Von Zahn, M, S Feuerriegel and N Kuehl (2022) ‘The cost of fairness in AI: Evidence from e-commerce’, Business & Information Systems Engineering 64(3): 335-348.

This Policy Brief benefitted from helpful discussions within Bruegel. Many thanks in particular to Antoine Mathieu Collin, Stephen Gardner and Bertin Martens for their helpful comments. This article is based on Bruegel Policy Brief Issue no31/25 | November 2025.