Paradise lost?

Fabio Panetta is a Member of the Executive Board of the ECB

Introduction

Some 15 years ago, software developers using the pseudonym Satoshi Nakamoto created the source code of what they thought could be decentralised digital cash1. Since then, crypto has relied on constantly creating new narratives to attract new investors, revealing incompatible views of what cryptoassets are or ought to be.

The vision of digital cash – of a decentralised payment infrastructure based on cryptography – went awry when blockchain networks became congested in 2017, resulting in soaring transaction fees2.

Subsequently, the narrative of digital gold gained momentum, sparking a ‘crypto rush’ that led to one in five adults in the United States and one in ten in Europe speculating on crypto, with a peak market capitalisation of €2.5 trillion3.

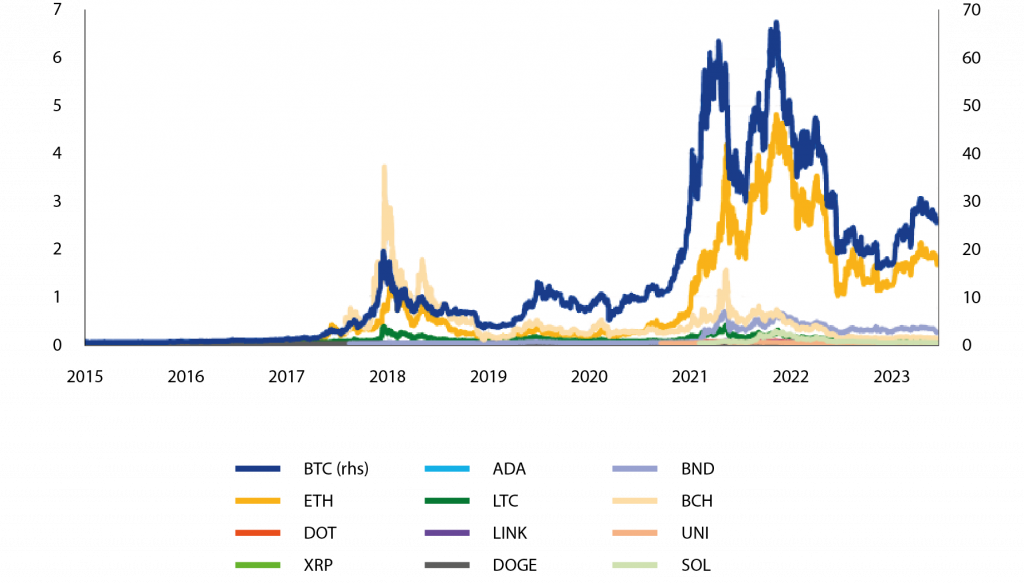

However, this illusion of cryptoassets serving as easy money and a robust store of value dissipated with the onset of the crypto winter in November 2021. The fall in the price of cryptos (Chart 1) led to a decrease of around €2 trillion worth of cryptoassets within less than a year. This caught millions of investors unprepared4. An estimated three-quarters of bitcoin users suffered losses on their initial investments at this time5.

Chart 1. Prices of bitcoin and selected altcoins (USD thousands).

Notes: The data are for the period from 1 January 2015 to 15 June 2023 and are based on the price of cryptoassets as in the Crypto Coin Comparison Aggregated Index (CCCAGG) provided by CryptoCompare. The altcoins’ names are abbreviated as follows: Bitcoin (BTC), Ether (ETH), Polkadot (DOT), Ripple (XRP), Cardano (ADA), Litecoin (LTC), Chainlink (LINK), Dogecoin (DOGE), Binance Coin (BNB), Bitcoin Cash (BCH), Uniswap (UNI), Solana (SOL).

Source: CryptoCompare.

Understandably, many are now questioning the future of cryptoassets. But the bursting of the bubble does not necessarily spell the end of cryptoassets6. People like to gamble and investing in crypto offers them a way to do so7.

Crypto valuations are highly volatile, reflecting the absence of any intrinsic value. This makes them particularly sensitive to changes in risk appetite and market narratives. The recent developments that have affected leading cryptoasset exchanges have highlighted the contradictions of a system which, though created to counteract the centralisation of the financial system, has become highly centralised itself.

I will contend that due to their limitations, cryptos have not developed into a form of finance that is innovative and robust, but have instead morphed into one that is deleterious. The crypto ecosystem is riddled with market failures and negative externalities, and it is bound to experience further market disruptions unless proper regulatory safeguards are put in place.

Policymakers should be wary of supporting an industry that has so far produced no societal benefits and is increasingly trying to integrate into the traditional financial system, both to acquire legitimacy as part of that system and to piggyback on it.

Instead, regulators should subject cryptos to rigorous regulatory standards, address their social cost, and treat unsound crypto models for what they truly are: a form of gambling.

This may prompt the ecosystem to make more effort to provide genuine value in the field of digital finance.

Shifting narratives: from decentralised payments to centralised gambling

The core promise of cryptos is to replace trust with technology, contending that the concept ‘code is law’ will allow a self-policing system to emerge, free of human judgement and error. This would in turn make it possible for money and finance to operate without trusted intermediaries.

However, this narrative often obfuscates reality. Unbacked cryptos have made no inroads into the conventional role of money. And they have progressively moved away from their original goal of decentralisation to increasingly rely on centralised solutions and market structures. They have become speculative assets8, as well as a means of circumventing capital controls, sanctions or financial regulation.

The crypto ecosystem is riddled with market failures and negative externalities, and it is bound to experience further market disruptions unless proper regulatory safeguards are put in place

Blockchain limitations

A key reason why cryptos have failed to make good on their claim to perform the role of money is technical. Indeed, the use of blockchain – particularly in the form of public, permissionless blockchain – for transacting cryptoassets has exhibited significant limitations9.

Transacting cryptos on blockchains can be inefficient, slow and expensive; they face the blockchain trilemma, whereby aiming for optimal levels of security, scalability and decentralisation at the same time is not achievable10.

Cryptoassets relying on a proof-of-work validation mechanism, which is especially relevant for bitcoin as the largest cryptoasset by market capitalisation11, are ecologically detrimental. Public authorities will therefore need to evaluate whether the outsized carbon footprint of certain cryptoassets undermines their green transition commitments12.

Moreover, proof-of-work validation mechanisms are inadequate for large-scale use13. Bitcoin, for example, can only accommodate up to seven transactions per second and fees can be exorbitant.

While alternative solutions to overcome the blockchain trilemma and proof-of-work consensus shortcomings have emerged for faster and more affordable transactions, including those outside the blockchain, they have drawbacks of their own. ‘Off-chain’ transactions conducted via third-party platforms compromise the core principles of cryptoassets, including security, validity and immutability14.

Another important aspect is the operational risk inherent in public blockchains due to the absence of an accountable central governance body that manages operations, incidents or code errors15.

Moreover, the handling of cryptoassets can be challenging. In a decentralised blockchain, users must protect their personal keys using self-custody wallets, which can discourage widespread adoption due to the tasks and risks involved, for example the theft or loss of a key. Given the immutability of blockchains, they do not permit transaction reversal16.

Instability

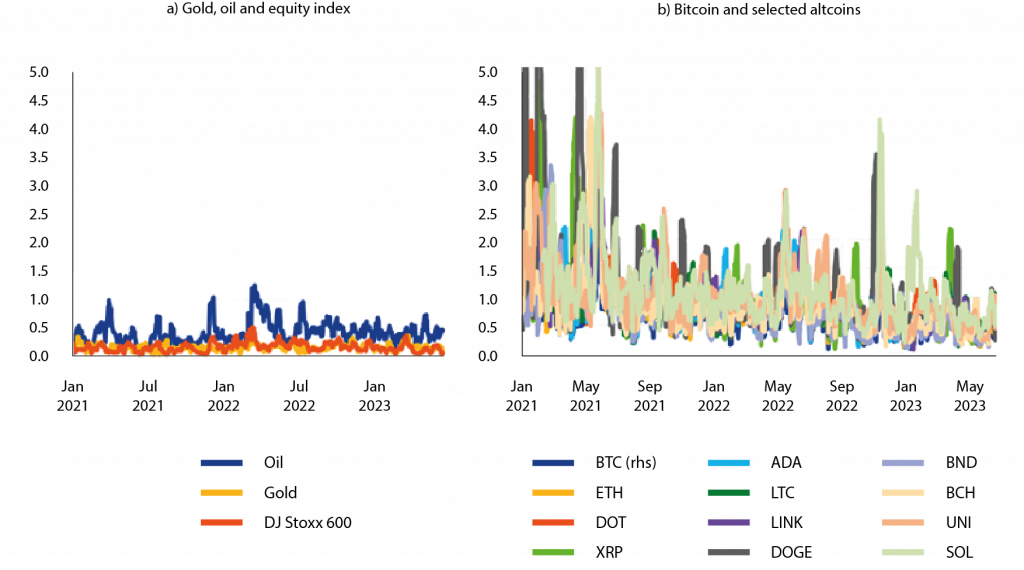

Another key limitation of unbacked cryptos is their instability. Unbacked cryptos lack intrinsic value and have no backing reserves or price stabilisation mechanisms17. This makes them inherently highly volatile and unsuitable as a means of payment. Bitcoin, for instance, exhibits volatility levels up to four times higher than stocks, or gold (Chart 2).

Chart 2. Price volatility of cryptos compared with other assets (annualised seven-day rolling standard deviation of daily percentage changes of prices).

Notes: The data are for the period from 1 January 2015 to 15 June 2023. For visibility reasons, the maximum of the y-axis for Chart 2, panel b is set to 5. Nevertheless, on 30 and 31 January 2021 the price volatility of DOGE exceeded 28. Oil data refer to the European Brent Spot price. The altcoins’ names are abbreviated as follows: Bitcoin (BTC), Ether (ETH), Polkadot (DOT), Ripple (XRP), Cardano (ADA), Litecoin (LTC), Chainlink (LINK), Dogecoin (DOGE), Binance Coin (BNB), Bitcoin Cash (BCH), Uniswap (UNI), Solana (SOL).

Sources: CryptoCompare, Bloomberg, Refinitiv and ECB calculations.

Such high volatility also means that households cannot rely on cryptoassets as a store of value to smooth their consumption over time. Similarly, firms cannot rely on cryptoassets as a unit of account for the calculation of prices or for their balance sheet.

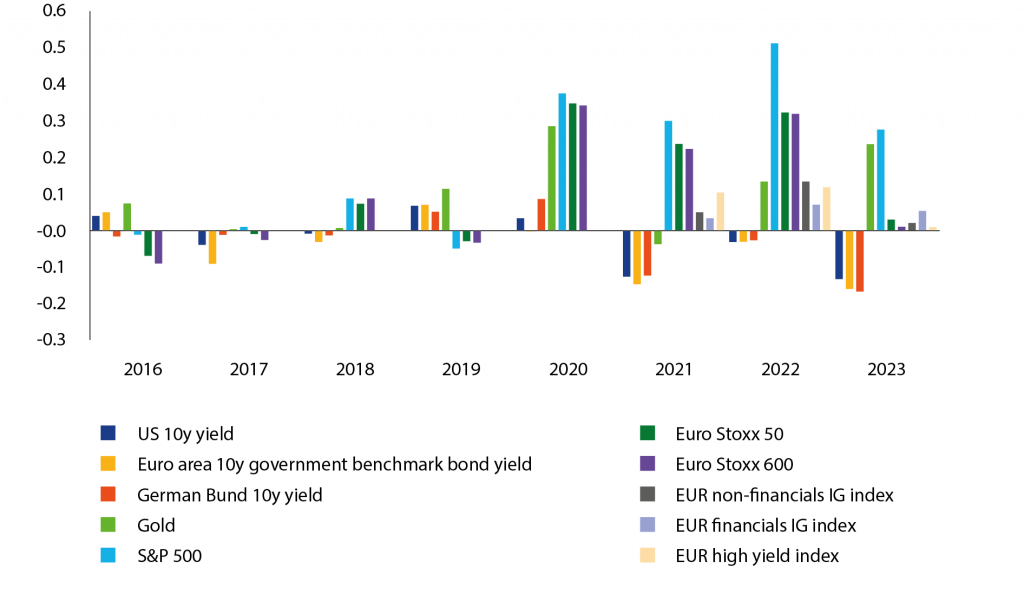

Moreover, unbacked cryptos do not improve our capacity to hedge against inflation. Indeed, their price developments exhibit an increasing correlation with stock markets (Chart 3). And empirical analysis finds that momentum in the cryptoasset market and global financial market volatility do have an impact on bitcoin trading against fiat currencies18.

Chart 3. Returns correlations of bitcoin vis-à-vis selected financial assets (yearly rolling correlation).

Notes: The data are for the period from 1 January 2016 to 16 June 2023.

Sources: Bloomberg, S&P Global iBoxx, CryptoCompare and ECB calculations.

Cryptos as a means of gambling and circumvention

But the very instability of unbacked cryptos does make them appealing as a means of gambling. And their use as such has been facilitated by the establishment of a centralised market structure that supports the broader use of cryptoassets19.

Crypto exchanges have become gateways into the crypto ecosystem, often providing user access to crypto markets in conjunction with other services like wallets, custody, staking20 or lending. Off-chain grids or third-party platforms have offered users easy and cost-effective ways to engage in trading and speculation, while stablecoins are being used to bridge the gap between fiat and crypto by promising a stable value relative to fiat currency21.

Besides gambling, cryptoassets are also being used for bypassing capital controls, sanctions and traditional financial regulation. A prime example is bitcoin, which is used to circumvent taxes and regulations, in particular to evade restrictions on international capital flows and foreign exchange transactions, including on remittances22.

These practices may have destabilising macroeconomic implications in some jurisdictions, notably in developing and emerging markets.

Risks from the growing centralisation of the crypto ecosystem

The crypto ecosystem’s move away from its original goals towards more centralised forms of organisation, typically without regulatory oversight, is giving rise to substantial costs and an array of contradictions. There are two major facets to this phenomenon.

The re-emergence of classic financial sector shortcomings and vulnerabilities

First, dependence on third-party intermediaries, many of which are still unregulated, has resulted in market failures and negative externalities, which crypto was initially designed to sidestep.

The crypto ecosystem, for instance, has cultivated its own concentration risks, with stablecoins assuming a key role in trading and liquidity provision within decentralised finance markets23. The difficulties faced by prominent stablecoins in the past year likely contributed significantly to the noticeable downturn in these markets24.

Indeed, stablecoins often pose greater risks than initially thought. They introduce into the crypto space the kind of maturity mismatches commonly seen in money market mutual funds. As we have seen in the past year, redemption at par at all times is not guaranteed, risks of runs and contagion are omnipresent, and liquidation of reserve assets can lead to procyclical effects through collateral chains across the crypto ecosystem.

Another episode of instability driven by high concentration risk was the fall of the crypto exchange FTX. Initially the crisis seemed to primarily affect liquidity, but it quickly evolved into a solvency crisis. This situation arose due to FTX’s inadequate risk management, unclear business boundaries and mishandling of customer funds.

The repercussions of this event rippled through the crypto ecosystem, causing cascading liquidations25 that underscored the interconnectedness and opacity of crypto markets. Ultimately, it showcased how swiftly confidence in the industry could deteriorate.

Similarities to the FTX case can be seen in the recent civil charges brought by the US Securities and Exchange Commission against the biggest remaining crypto exchange: Binance. These civil charges allege that Binance’s CEO and Binance entities were involved in an extensive web of deception, conflicts of interest, lack of disclosure and calculated evasion of the law26. Should these allegations be proven, this would be yet another example of the fundamental shortcomings of the crypto ecosystem.

The recent crypto failures also show that risk, in itself, is technology-neutral. In financial services, it does not matter if a business ledger is kept on paper as it was for hundreds of years, in a centralised system as we have now or on a blockchain as in the cryptoasset ecosystem.

In the end, whether a firm remains in business or fails depends on how it manages credit risk, market risk, liquidity risk and leverage. Crypto enthusiasts would do well to remember that new technology does not make financial risk disappear. The financial risk either remains or transforms into a different type.

It is like pressing a balloon on one side: it will change in shape until it pops on the other side. And if the balloon is full of hot air, it may rise for a while but will burst in the end.

Links with the traditional financial sector

The second contradiction arises from the crypto industry’s attempt to strengthen ties with actors in the financial system, including banks, big tech companies and the public sector.

Major payment networks27 and intermediaries28 have enhanced their support services for cryptoassets. Numerous prominent tech companies, including Meta (formerly Facebook) and Twitter, have explored ways to incorporate crypto into their platforms29.

By leveraging their large customer base and offering a mix of payments and other financial services, tech firms, especially big techs, could solidify the ties between cryptoassets and the financial system.

The recent failures of Silvergate Bank and Signature Bank have highlighted the risks for banks associated with raising deposits from the crypto sector. The stability of these deposits is questionable given cryptos’ volatility.

The discontinuation of the Silvergate Exchange Network and SigNet, which functioned as a quasi-payment system for the crypto investments of Silvergate Bank and Signature Bank clients, also shows how cryptoassets service providers depend on the traditional financial sector for settlement in fiat money.

The crypto industry not only seeks to strengthen its ties with the traditional financial industry. It also seeks to gain access to the public safety net that strongly regulated financial entities benefit from30.

Indeed, Circle, the issuer of the USD Coin (USDC) tried to gain access to the Federal Reserve’s overnight reverse repurchasing facility in order to back its stablecoin31.

The crypto industry is seeking to grow by parasitising the financial system: it touts itself as an alternative to the financial sector, yet it seeks shelter within that very sector to address its inherent risks, all in the absence of adequate regulatory safeguards.

The public response: backing, regulating or innovating?

The public sector response can be encapsulated in three main suggestions.

Not giving in to the temptation to offer public backing to cryptos

First, the temptation to offer public backing to cryptos must be resisted.

The idea of permitting stablecoin issuers as non-bank financial institutions to hold their reserves at central banks might seem appealing, but could lead to serious adverse consequences.

By granting stablecoins access to the central bank’s balance sheet, we would effectively outsource the provision of central bank money. If the stablecoin issuer were able to invest its reserve assets32 in the form of risk-free deposits at the central bank, this would eliminate the investment risks that ultimately fall on the shoulders of stablecoin holders. And the stablecoin issuer could offer the stablecoin holders a means of payment that would be a close substitute for central bank money33.

This would compromise monetary sovereignty, financial stability and the smooth operation of the payment system. For example, a stablecoin could displace sovereign money by using the large customer network of a big tech, with far-reaching implications34. Therefore, central banks should exercise prudence and retain control over their balance sheet and the money supply.

Regulating cryptos adequately and comprehensively

Second, regulators should refrain from implying that regulation can transform cryptoassets into safe assets. Efforts to legitimise unsound crypto models in a bid to attract crypto activities should be avoided35.

Moreover, the principle of ‘same activity, same risk, same regulation’ should be endorsed. Cryptos cannot become as safe as other assets and investors should be aware of the risks. Anti-money laundering/countering the financing of terrorism rules should be enforced, and crypto activities of traditional firms should be carefully monitored.

While some jurisdictions attempt to apply existing regulatory frameworks to cryptoassets, the EU’s Markets in Crypto-Assets Regulation offers a customised regulatory structure that applies to all 27 EU member states and draws on existing regulation where appropriate (e-money being one example). The EU has also updated existing regulation, for instance by extending the travel rule to crypto transactions36.

Despite the EU taking the lead in establishing a comprehensive framework regulating crypto activities, further steps are necessary. All activities related to the crypto industry should be regulated, including decentralised finance activities like cryptoasset lending or non-custodial wallet services37.

Moreover, the regulatory framework for unbacked cryptoassets may be deemed lighter than for stablecoins as it relies mainly on disclosure requirements for issuing white papers38, and on the supervision of the service providers which will offer them for trading. The risks posed by unbacked cryptoassets, which are largely used for speculative purposes, should be fully recognised.

Enhancing transparency and awareness of the risks associated with cryptoassets and their social cost are critical aspects of this approach. Public authorities will also need to address those social costs: for instance, cryptos’ ecological footprint cannot be ignored in view of environmental challenges.

Additionally, the experience of FTX, which expanded massively with little oversight, underscores the importance of global crypto regulation and regulatory cooperation. The Financial Stability Board’s recommendations39 for the regulation and oversight of cryptoasset activities and markets need to be finalised and implemented urgently, also in non-FSB jurisdictions.

The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision’s standard on the prudential treatment of banks’ cryptoasset exposures is a positive step in this direction. It stipulates conservative capital requirements for unbacked cryptoassets with a risk weight of 1,250%, as well as an exposure limit constraining the total amount of unbacked crypto a bank can hold to generally below 1% of Tier 1 capital.

It will be key for the European Union and other Basel jurisdictions to transpose the Basel standard into their legislation by the 1 January 2025 deadline40. However, regulation alone will not be sufficient.

Innovating: digital settlement assets and central bank digital currencies

Third, the public sector needs to contribute to the development of reliable digital settlement assets.

Central banks are innovating to provide a stability anchor that maintains trust in all forms of money in the digital age. Central bank money for retail use is currently only available in physical form – cash. But the digitisation of payments is diminishing the role of cash and its capacity to provide an effective monetary anchor.

A central bank digital currency would offer a digital, risk-free standard and facilitate convertibility among different forms of private digital money. It would uphold the singleness of money and protect monetary sovereignty. We are advancing with our digital euro project and aim to complete our investigation phase later this year.

Furthermore, the tokenisation of digital finance may require central banks to modify their technological infrastructure supporting the issuance of central bank money for wholesale transactions. This could involve establishing a bridge between market distributed ledger technology (DLT) platforms and central bank infrastructures, or a new DLT-based wholesale settlement service with DLT-based central bank money41. We will involve the market in the exploratory work that we have recently announced42.

Conclusion

Cryptoassets have been promoted as decentralised alternatives promising more resilient financial services. However, the reality does not live up to that promise. The blockchain technology underpinning cryptoassets can be extremely slow, energy-intensive and insufficiently scalable. The practicality of cryptoassets for everyday transactions is low due to their complex handling and significant price volatility.

To address these drawbacks, the crypto ecosystem has changed its narrative, favouring more centralised forms of organisation that emphasise crypto speculation and quick profit. But recent events have exposed the fragility of the crypto ecosystem, demonstrating how quickly confidence in cryptoassets can evaporate.

In many respects, this ecosystem has recreated the very shortcomings and vulnerabilities that blockchain technology initially intended to address.

Further complicating matters, the crypto market seeks integration into the financial sector for increased relevance and public sector support. This would not provide the basis of a sustainable future for crypto. If anything, it would only heighten contradictions and vulnerabilities, resulting in greater instability and centralisation.

The public sector should adopt a determined position by establishing a comprehensive regulatory framework that addresses the social and environmental risks associated with crypto, including the use of unbacked cryptoassets for speculative purposes.

It should also resist calls to provide state backing for cryptos, which would essentially socialise crypto risks. The public sector should instead focus its efforts on contributing to the development of reliable digital settlement assets, including through their work on central bank digital currencies.

Decisive action of this kind should motivate the crypto ecosystem, including its foundational technology, the blockchain, to realign its objectives towards delivering real economic value within the digital finance landscape.

Endnotes

1. See Nakamoto, S (2008), “Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System”, bitcoin.org.

2. To maintain a system of decentralised consensus on a blockchain, self-interested validators need to be rewarded for recording transactions. In order to achieve sufficiently high rewards, the number of transactions per block needs to be limited. As transactions near this limit, congestion increases the cost of transactions exponentially. See Boissay et al (2022), “Blockchain scalability and the fragmentation of crypto”, BIS Bulletin, No 56, Bank for International Settlements, 7 June.

3. It should be noted that holdings of cryptoassets are often concentrated in the hands of a few holders who could influence supply and prices. Moreover, some investments are the proceeds of illicit activities, which may be price elastic.

4. The market capitalisation of cryptoassets decreased from its peak of around €2.68 trillion on 10 November 2021 to €801 billion on 2 July 2022. By 14 June 2023 it stood at €978 billion. Source: CoinMarketCap.

5. See Auer et al (2022), “Crypto trading and Bitcoin prices: evidence from a new database of retail adoption”, BIS Working Papers, No 1049, Bank for International Settlements, November.

6. See Panetta, F (2023), “Caveat emptor does not apply to crypto”, The ECB Blog, 5 January.

7. See Panetta, F (2022), “Crypto dominos: the bursting crypto bubbles and the destiny of digital finance”, speech at the Insight Summit, London Business School, 7 December.

8. Incidences of fraud, human error and manipulation have eroded the trust of crypto enthusiasts, leading to calls for scrutiny, oversight and public intervention. Research and analysis show that fully decentralised set-ups are often concentrated on few holders or require other types of human intervention. This makes them prone to manipulation and risks. See for example, Sayeed and Marco-Gisbert (2019), “Assessing Blockchain Consensus and Security Mechanisms against the 51% Attack”, Applied Sciences, Vol. 9, No 9, April.

9. Blockchain technology may however be well-suited to other areas, for instance, supply chain management.

10. See S Shukla (2022), The ‘Blockchain Trilemma’ That’s Holding Back Crypto, The Washington Post, 11 September.

11. As of 14 June bitcoin had a market capitalisation of €465.92 billion. Source: CoinGecko.

12. See Gschossmann, I van der Kraaij, A, Benoit, P-L and Rocher, E (2022), “Mining the environment – is climate risk priced into crypto-assets?”, ECB Macroprudential Bulletin, 11 July.

13. Moreover, Makarov and Schoar show that bitcoin mining is highly concentrated: the top 10% of miners control 90% of mining capacity and just 0.1% (about 50 miners) control close to 50% of mining capacity. Alternatively, blockchains based on proof of stake are faster, but also tend towards centralisation, as larger coin holders can reap more rewards, concentrating power and the risk of 51% attacks. See Makarov, I and Schoar, A (2022), “Blockchain Analysis of the Bitcoin Market”, NBER Working Papers, No 29396, National Bureau of Economic Research, 18 April.

14. See Soares, X (2023), “On-Chain vs. Off-Chain Transactions: What’s the Difference?”, CoinDesk, 11 May.

15. See Walch, A (2018), “Chapter 11 – Open-Source Operational Risk: Should Public Blockchains Serve as Financial Market Infrastructures?”, in Chuen, DLK and Deng, R (eds.), Handbook of Blockchain, Digital Finance, and Inclusion, Vol. 2, Academic Press, pp. 243-269.

16. Moreover, the fact that data stored on the blockchain is immutable and transparent may put the technology in conflict with digital privacy rights.

17. In the absence of flexible supply mechanisms, unbacked cryptos are incapable of effectively responding to temporary fluctuations in demand and thus fail to stabilise their value. Similarly, bitcoin’s limited supply – at 21 million coins – means that it does not offer protection against the risk of structural deflation.

18. Di Casola, P, Habib, M and Tercero-Lucas, D (2023), “Global and local drivers of Bitcoin trading vis-à-vis fiat currencies”, ECB Working Paper Series, forthcoming.

19. The industry’s trend towards centralisation is clear. Since 2015 approximately 75% of the actual bitcoin volume has been associated with exchanges or exchange-like entities, including online wallets, over-the-counter (OTC) desks and large institutional traders. See Makarov and Schoar (2022), op. cit.

20. Staking is the foundation of the proof-of-stake consensus mechanism, which entails individuals locking up their assets (native coins) on a blockchain to secure the protocol. The stake acts as a form of collateral to ensure that validators, who are responsible for verifying and appending the blockchain, act in a manner that is in line with the protocol’s rules. See Oderbolz, N, Marosvölgyi, B and Hafner, M (2023), “The Economics of Crypto Staking”, Swiss Economics Blog, 1 March.

21. They back their value with securities, commodities, as well as fiat money. Interestingly and inevitably, major stablecoin issuers – such as Tether or Circle – adopt centralised organisational structures, directly contradicting the initial ideas as laid down in Satoshi Nakamoto’s white paper. The notion that stablecoin issuers might invest in cryptoassets could further concentrate holdings and contradict the low-risk requirements for stablecoin reserves.

22. Graf von Luckner, C, Reinhart, CM and Rogoff, K (2023), “Decrypting new age international capital flows”, Journal of Monetary Economics, 1 June.

23. Although it represents only a small part of the cryptoasset market, the stablecoin Tether accounts for close to half of all trading on cryptoasset trading platforms. See the section entitled “Stablecoins’ role within the crypto-asset ecosystem” in Adachi, M et al (2022), “Stablecoins’ role in crypto and beyond: functions, risks and policy”, Macroprudential Bulletin, Issue 18, ECB.

24. See the May 2023 report by the ESRB Task Force on Crypto-Assets and Decentralised Finance entitled “Crypto-assets and decentralised finance”.

25. A decentralised finance ecosystem is built around crypto lending that is collateralised by other cryptoassets, using smart contracts to implement margin calls. The failure of FTX had a large impact on the price of cryptoassets serving as collateral for crypto lending. This triggered cascading liquidations by crypto lenders because of the decrease in the value of the collateral.

26. See US Securities and Exchange Commission (2023), SEC Files 13 Charges Against Binance Entities and Founder Changpeng Zhao, 5 June.

27. In particular, Mastercard, PayPal and Visa continue building capabilities and strategic partnerships to support cryptoassets (as well as stablecoins).

28. See, for example, JP Morgan’s Onyx Coin Systems Product Team, Fidelity’s Fidelity CryptoSM Account and Citi’s collaboration with METACO to develop and pilot digital asset custody capabilities.

29. Meta expressed interest in the metaverse and the potential integration of cryptoassets and blockchain technology within its virtual reality platform. The company has been exploring the concept of a blockchain-based digital currency called ‘Facebook Diem’ (previously known as Libra). Twitter has integrated bitcoin tipping features. It allows users to send and receive bitcoin tips to content creators and other users on the platform.

30. See PYMTS (2023), Circle Says Lack of Direct EMI Access to EU Central Bank Accounts Stifles Payments Innovation.

31. Circle’s USD 31 billion USDC stablecoin maintains around USD 25 billion of its reserves in short-term US Treasury bills in the exclusive Circle Reserve Fund, managed by BlackRock. The fund is registered as a ‘2a-7’ government money market fund. Circle’s objective for the fund was to secure access to the Federal Reserve’s reverse repurchasing facility through BlackRock, allowing the company to move USDC’s remaining cash reserves from partner banks to the fund under a Federal Reserve account.

32. Reserve assets are the assets against which the stablecoins are valued and redeemed.

33. In contrast, the substitutability between central bank money and bank deposits is limited by the fact that, on bank balance sheets, deposits are matched against risky assets (bank loans).

34. See Panetta, F (2020), “From the payments revolution to the reinvention of money”, speech at the Deutsche Bundesbank conference on the “Future of Payments in Europe”, 27 November.

35. See Chipolina, S and Asgari, N (2023), “Binance slams US crypto crackdown and makes bid for UK oversight”, Financial Times, 10 May.

36. The ‘travel rule’, already used in traditional finance, will in the future cover transfers of cryptoassets. Information on the source of the asset and its beneficiary will have to ‘travel’ with the transaction and be stored on both sides of the transfer. The law also covers transactions above €1,000 from ‘self-hosted wallets’ (a cryptoasset wallet address of a private user) when they interact with hosted wallets managed by cryptoasset service providers. See Regulation (EU) 2023/1113 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 31 May 2023 on information accompanying transfers of funds and certain cryptoassets and amending Directive (EU) 2015/849 (Text with EEA relevance), Official Journal L 150, 9 June 2023, p. 1–39.

37. Crypto lending is a centralised or decentralised finance service that allows investors to lend out their crypto holdings to borrowers. Decentralised crypto lending platforms use smart contracts to automate loan payouts and yields, and users can deposit collateral to receive a loan if they meet the appropriate requirements automatically (see Duggan, W (2023), “Crypto Lending: Earn Money From Your Crypto Holdings”, Forbes, 30 January). A non-custodial wallet, or self-custody wallet, entails the crypto owner being fully responsible for managing their own cryptos. The users have full control of their crypto holdings, manage their own private key and handle transactions themselves (see “Custodial vs Non-Custodial Wallets”, crypto.com, 17 February 2023).

38. This is a sort of prospectus for cryptoassets that informs potential holders about the characteristics of the issued cryptoasset before they offer a token to the public or list it on a trading platform.

39. See Financial Stability Board (2023), “Crypto-assets and Global “Stablecoins”.

40. See European Central Bank (2023), “Crypto-assets: a new standard for banks”, Supervision Newsletter, 15 February.

41. Panetta, F (2022), “Demystifying wholesale central bank digital currency”, speech at the Deutsche Bundesbank’s Symposium on “Payments and Securities Settlement in Europe – today and tomorrow”, Frankfurt am Main, 26 September.

42. European Central Bank (2023), “Eurosystem to explore new technologies for wholesale central bank money settlement”, Frankfurt am Main, 28 April.

This article is based on a speech delivered at a panel on the future of crypto at the 22nd BIS Annual Conference, 23 June 2023.