Improving the contestability of e-commerce in two jurisdictions: the Amazon case

Fiona Scott Morton is a Non-Resident Fellow at Bruegel

Executive summary

Antitrust cases against Amazon in the United States reveal that the e-commerce giant has developed algorithms that mimic price protection contracts called MFNs (from most-favoured nations, a term borrowed from international trade), despite the company saying publicly that it ended the contracts themselves some years ago.

MFNs are well known in antitrust enforcement for their anticompetitive effects: higher prices and less entry. The complaints describe how Amazon demotes merchants from its coveted Buy Box if Amazon finds a lower price on a rival e-commerce site, creating an incentive for merchants to set higher prices on rival sites.

The European Union, the Digital Markets Act bans such contracts. This would be a good remedy for the US as well as it would restore competition with minimal harmful side effects. The US complaints describe a different scheme that penalises brands if Amazon must reduce its retail prices to match a rival retailer. The EU may have to pursue this conduct under Article 102 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union that prohibits abuse of dominance.

Both the US Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and the European Commission have found that Amazon’s policy of tying its own logistics service to Amazon Prime status raises entry barriers to rivals. The European Union remedy redesigns the Buy Box and allows rival logistics services access to consumers.

This remedy provides a useful benchmark to consider in designing remedies for the FTC and for California, which is also pursuing an antitrust case against Amazon. In general, both the US and the EU gain from the enforcement actions of the other.

1 Introduction

Improving competition in digital markets is a priority for the governments in both the United States and Europe. In the European Union, this can be seen in the Digital Services Act, the Data Act, and most importantly, the Digital Markets Act. In the US, the desire for more competition can be seen in the Biden Administration’s appointments of leaders of the antitrust agencies who have brought several antitrust cases against digital platforms.

Amazon is one of the big-tech companies that receives regular criticism from politicians and the media. In the US, several antitrust cases against Amazon are currently in litigation, including those brought by the state of California (filed September 2022; Superior Court of the State of California, 2022) and the Federal Trade Commission and 17 states (filed September 2023; FTC, 2023).

These cases may have a bearing on enforcement against Amazon in Europe, where regulators have also been busy: an antitrust case brought against Amazon by the European Commission was resolved with commitments in December 2022 and commitments were also accepted in 2023 by the United Kingdom Competition and Markets Authority1.

In addition, the European Commission has designated Amazon’s e-commerce business as a core platform service2, meaning it will have to comply with the EU Digital Markets Act (Regulation (EU) 2022/1925) beginning in March 2024.

The conduct described in the US complaints against Amazon harms competition between online stores and among the merchants who sell via them. The first harm is the suppression of price competition between e-commerce platforms.

The second harm occurs when Amazon’s market power reduces competition in the logistics that merchants use to support their e-commerce sales. If they are available, independent logistics firms lower the cost of entry of rival e-commerce platforms and thereby increase competition. The evidence in this context unearthed in the US investigations is highly relevant to successful enforcement in the EU.

Meanwhile, Amazon’s commitments to the European Commission, and DMA provisions that apply to Amazon’s core platform services, should increase contestability and fairness in e-commerce markets. As this Policy Brief details, the combination of these policies can be effective in giving merchants more choices and lowering barriers to entry to Amazon’s competitors.

The US lags behind Europe in competition enforcement of e-commerce, and so US authorities can learn from such European solutions. Likewise EU regulators can learn from US antitrust enforcement. Regulators on both sides of the Atlantic can build on the enforcement activities of each other. More robust solutions will create more contestability and fairness for consumers and businesses.

2 Stifling price competition

2.1 How Amazon’s alleged conduct controls prices on rival marketplaces

The California and FTC complaints both accuse Amazon of operating what are effectively ‘platform MFNs’ (most-favoured nation commitments, a term borrowed from international trade) for third-party marketplace sellers and the brand representatives.

Platform MFNs are requirements that third-party sellers on a platform, in this case a marketplace, set prices for the same good on competing marketplaces that are at least as high as those found on the platform requiring the MFN.

The MFN thus controls prices on the seller’s own website and on competing marketplaces. These contracts end price competition between marketplaces because all prices for the good are the same. Furthermore, a merchant selling on a marketplace with lower fees cannot pass those lower fees through to consumers in the form of lower prices, without – under the terms of the MFN – also lowering the price of the good on the primary platform, in this case Amazon, which has higher fees.

Therefore, a lower-priced entrant platform has no way to attract customers with lower prices if it wants to sell the products of merchants covered by the Amazon platform MFN. For this reason, platform MFNs also limit competition between marketplaces (Baker and Scott Morton, 2018).

A large economics literature3 confirms these intuitions: sellers will choose to set high prices on all competing sites to match those on a large platform with an MFN. This harms competition in goods. Second, the competing marketplace now has no reason to lower its fees, since it cannot gain more business that way. This harms competition between the marketplaces themselves and deters entry of more efficient marketplaces.

This economic logic is well-known among enforcers. MFN contracts have therefore been a frequent target of enforcement efforts in many industries. In 2013 Germany and the UK opened investigations into Amazon’s MFN contracts, which caused the company to abandon them in Europe (Bundeskartellamt, 2013).

In 2019, at the instigation of Senator Richard Blumenthal (not the FTC), Amazon voluntarily ended its MFN contracts in the United States. Observers might well think, therefore, that the anticompetitive effects of these contracts are gone.

2.2 De-jure versus de-facto MFNs

However, the US lawsuits set out the steps Amazon took to purposefully recreate the effects of the MFN contracts after it ended them formally. Both the California and FTC complaints describe the replacement tactics Amazon has used to control off-platform prices through the Amazon Standards for Brands policy (ASB), the Marketplace Fair Pricing Policy, the Seller Code of Conduct and Select Competitor – Featured Offer Disqualification (SC-FOD) (Superior Court of the State of California, 2022 (hereafter ‘Cal Comp’) paragraph 125; FTC, 2023 (hereafter FTC), paragraphs 276, 297).

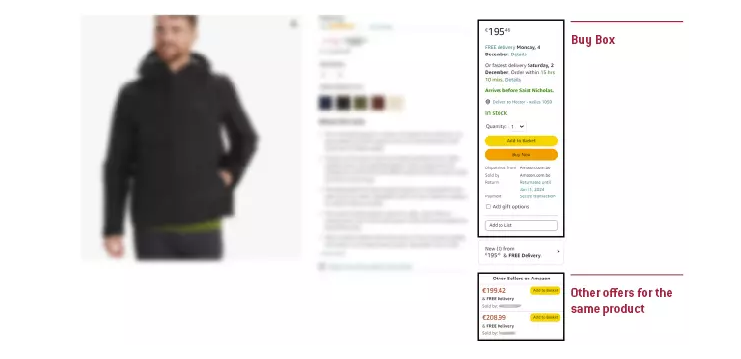

If a seller’s prices are lower on a rival site (FTC ¶ 277), Amazon downgrades the listing of the good, and removes it from eligibility for the ‘Buy Box’ or ‘featured offer’ (FTC ¶ 84) (the Buy Box is the familiar box on the top right of the Amazon product page; it shows one seller that Amazon has chosen and, by virtue of the design of the box, is made more prominent than any other seller).

Given Amazon’s huge consumer base, and the fact that 98 percent of purchases occur through users choosing the seller in the Buy Box (FTC ¶ 85), an excluded merchant is likely to lose significant sales with this downgrade.

Furthermore, the California and FTC complaints are detailed in their evidence that Amazon’s managers were aware of the purpose of the programmes. For example, SC-FOD was designed to enforce the contractual MFN’s “expectations and policies,” which “had not changed” (FTC ¶ 276). The FTC complaint states:

“At one time, Amazon designated only the very largest online stores as ‘Select Competitors’ for purposes of SC-FOD. After dropping the price parity clause from its Business Solutions Agreement, Amazon exponentially expanded its classification of ‘Select Competitors.’[…] According to a senior Amazon executive, Amazon expanded the designation of Select Competitors] to make “the punitive aspect” of SC-FOD “more effective”” (FTC ¶ 280).

Both complaints explain that Amazon’s Standards for Brands, or ASB programme, contractually requires certain third-party sellers to “ensure that their products’ prices on other online stores are as high or higher than their prices on Amazon at least 95% of the time” and imposes additional restrictions on sellers’ inventory and Amazon Prime membership4 so they effectively cannot sell anywhere but on Amazon (FTC ¶¶ 291-2; Cal Comp ¶¶ 145-8).

As with the SC-FOD programme, Amazon was clear about why it penalised ASB sellers who did not meet the programme’s requirements: “Amazon told those punished ASB sellers that they were being sanctioned because ‘customers considering your products could have easily found your products cheaper at another major retailer, and may have chosen to shop elsewhere’” (FTC ¶ 297). These statements should raise concerns in all jurisdictions that Amazon’s contractual MFNs were only a small part of the competition problem.

The US lags behind Europe in competition enforcement of e-commerce and US authorities can learn from European solutions

2.3 How Amazon’s alleged conduct controls prices on rival retail sites

The California complaint describes behaviour that also creates an effective MFN in Amazon’s retail operation. Amazon’s retail business differs from the marketplace business because Amazon itself buys goods at wholesale prices, owns those goods, and then sells them via its own website at prices it chooses. A marketplace, by contrast, hosts independent merchants that control what they sell and how it is delivered, and set their own prices.

As described in the complaint, brands that sell wholesale to Amazon fare even worse than re-sellers because of another MFN-like scheme. Amazon requires brands to agree to a contract called a Minimum Margin Agreement (Cal Comp ¶¶175-204). Amazon uses an algorithm to reduce its retail prices if it finds a lower price for the same product on a rival website, such as Walmart.com.

But the brand Amazon buys from wholesale remains responsible for maintaining Amazon’s profit margin. The brand must therefore make up the difference between the price initially set by Amazon, and the lower price that Amazon has matched. This is true even though the brand itself does not choose the retail price in either setting; the online stores have that responsibility.

The result of this scheme is that whenever Walmart.com, for example, has a sale on a certain product or brand, Amazon matches the sale price, and its profit margin may fall below its target level. If so, Amazon requires the brand to compensate it for the new low price.

Naturally, this penalty causes the brand to want to sell to Walmart.com at a high enough wholesale price so that Amazon’s retail price will always be lower than Walmart’s. In general, a brand does not want to offer discounts to Walmart because that might encourage a sale that would cause the brand to suffer if Walmart.com decides to lower prices for any reason, eg. to attract consumers to its store.

The brand might even withdraw from Walmart.com altogether if such sales cause it to owe large sums to Amazon. Internal Amazon documents acknowledge the “punitive aspect” of this scheme (FTC ¶ 282). The anticompetitive impact of this programme is the same as an MFN in its ability to raise prices at rival stores.

2.4 What remedies would restore vigorous price competition?

Assuming that the allegations about MFNs described in the preceding subsections are proved, agencies or courts will need to impose remedies to restore the lost competition. The simplest remedy is to ban MFNs entirely: wide MFNs (which cover prices in rival e-commerce stores), narrow MFNs (which cover prices on the website of the brand itself) and any conduct that creates the same incentives as an MFN. The EU has already banned MFNs in Article 5(3) of the Digital Markets Act.

To explain the impact of an MFN ban on the strategies of all parties, it is useful to consider two questions. First, for the MFN to be triggered, a rival must offer a lower price.

Why is a rival e-commerce store setting a retail price lower than Amazon’s price?

1. The rival store has lower costs of operation than Amazon;

2. The rival platform bought the good from its manufacturer for a lower price; or

3. The rival platform has a different strategy or weaker market position than Amazon and lower prices are the best way to attract consumers.

These answers are standard manifestations of competition that benefits consumers. If prices are lower on a rival e-commerce site for any of these reasons, consumers gain, and the law should not permit Amazon to implement contracts or policies that suppress that competition.

If Amazon wishes to retain customers after this MFN is banned, it can bring down its fees or raise its value. Likewise, Amazon can bargain for a lower price from the manufacturer, or possibly cut its costs by making its own-label version of the product.

The second question when assessing the potential impact of an MFN ban has to do with re-sellers:

Why is a third-party reseller setting a price on Amazon that is higher than on other platforms?

4. It thinks Amazon shoppers are inattentive and not price-responsive and is exploiting them with a high price; or

5. Its costs are lower on rival platforms because those platforms’ fees are lower.

A reseller is not violating competition laws if it chooses to set different prices in different distribution channels for reasons such as differences in cost or demand. But, of course, this conduct hurts Amazon shoppers and Amazon’s brand. A remedy that restores the lost competition in fees (5) should ideally allow Amazon to protect its own consumers from any possible exploitation in (4).

Handily, Amazon has already built the tool needed to combat the possible exploitation in (4): the Buy Box. When third-party sellers list on Amazon, the firm’s algorithm evaluates their offers and puts the one that meets its criteria into the Buy Box (see the annex for an illustration). Consumers with ranking bias and default bias tend to purchase the option in the Buy Box, meaning that the winning seller typically obtains 98 percent of sales (according to the FTC complaint).

Annex: The Buy Box

If Amazon’s algorithm weights high prices negatively, a third-party seller engaging in the exploitation in (4) would be expected to sell very little because it is not in the Buy Box and, if any diligent consumers search the listing, they will find an exploitative price – which will limit sales.

The design of the Buy Box means it can be used legitimately by Amazon to defend consumers on Amazon Marketplace from exploitation by high-priced sellers. Thus, it duplicates the pro-competitive impact of the MFN without the anticompetitive element and can be used to replace it when the MFN is banned. Because the Buy Box is only for prices on the Amazon platform, it does not duplicate the restraint on horizontal competition that characterises an MFN.

Now consider the case of a product sold by only one reseller on Amazon, and which that re-seller is pricing in an exploitative manner. The Buy Box cannot fix this problem. However, Amazon has the incentive and ability to recruit another reseller to its platform. Entry will be attractive for the new seller because undercutting the incumbent’s exploitative price still allows for a healthy margin.

Thus, both Amazon and rival third-party sellers have an incentive to defeat the conduct described in (4), while Amazon has the information to identify the opportunity and the ability to facilitate entry of lower-priced rivals.

If there is only one original seller of the product, such as the brand itself, there is also nothing for the Buy Box to leverage. But Amazon has procompetitive tools to combat this strategy. For example, the brand’s listing on the search-results page could truthfully explain to the customer what the brand’s regular list price is and could recommend substitute products on Amazon that are not overpriced – all without removing the ability to buy the brand in the normal way.

An Amazon premium here could occur because the cost of selling is higher on Amazon. If the brand finds the costs of selling on Amazon to be higher than on other platforms, either because of advertising that is effectively required, or high fees charged by the platform, it may build those costs into the price it charges.

This is a normal feature of competition. Customers will evaluate the benefits of the Amazon platform (OneClick purchasing, fast delivery, saved addresses) and compare them to the price difference. If the latter outweighs the former, the customer will leave Amazon to buy the brand for a lower price elsewhere.

A reasonable concern is that a ban on MFNs will lead to inefficient free-riding (showrooming). This occurs when sellers use the dominant platform to display their product and attract buyers, but then encourage those buyers to purchase off the platform, thereby avoiding the platform’s fees. This can reduce below the optimal level the incentive to build and invest in a platform.

However, a consumer who sees a product on Amazon and searches for the seller’s page to buy it at a lower price is giving up all the services of Amazon: saved payment, saved addresses and quick delivery times. Amazon itself touts the superiority of its services and the stickiness it creates with time- and attention-strapped consumers.

The government complaints contain quotations from managers at the company that acknowledge high switching costs for consumers (FTC ¶ 182). For these reasons, free-riding may be minimal.

3 Stifling entry of competitors

3.1 The link between shopping and fulfilment

Additional allegedly illegal conduct described by the FTC relates to the tying of fulfilment by Amazon (FBA) membership to participation in Prime (and therefore sales, as noted above). Formerly, merchants could use their own fulfilment and delivery services within the Prime programme (called SFP, or seller-fulfilled Prime) (FTC ¶ 400).

The merchants that participated in SFP could have their listings qualify for Prime, and therefore the Buy Box, but also could send out those items using a logistics provider of their choice, rather than using Amazon.

This is important because such a merchant can then also fulfil sales from rival e-commerce platforms with the same logistics infrastructure they use for Amazon sales. This promotes the entry of rival e-commerce marketplaces because, by virtue of hosting the same sellers on their platforms, their delivery quality and cost is similar to Amazon’s.

When Amazon banned SFP or made it difficult5, most Amazon merchants turned to FBA, which does not have this beneficial effect on rival marketplaces.

The FTC’s complaint emphasises this impact on competition, namely that the decline in availability of independent fulfilment and logistics services at scale reduced entry and growth of rival e-commerce stores. When SFP reduced multihoming across e-commerce marketplaces, that reduced competition between marketplaces (FTC ¶ 405).

Amazon executives appreciated the value of the lessened competition, according to the FTC complaint. An Amazon executive stated that the mere prospect of increased competition for fulfilment services “keeps me up at night” (FTC ¶ 391).

Another executive “explained to his colleagues that he had an ‘oh crap’ moment when he realized that this was ‘fundamentally weakening [Amazon’s] competitive advantage in the US as sellers are now incented [sic] to run their own warehouses and enable other marketplaces with inventory that in FBA would only be available to our customers” (FTC ¶ 31).

3.2 Fairness concerns

The FTC complaint tracks the concerns expressed by the European Commission about the way in which the design of the Buy Box effectively required sellers to participate in Prime and therefore to use FBA. However, that similarity masks an interesting element to the European case. The Italian competition authority started its investigation6 because local rival logistics operators wanted to be included by Amazon on an equal basis to Amazon’s logistics.

The conflict with Amazon arose because of the possibility that rival logistics providers have slower delivery times. The open question is whether Amazon treats rival logistics providers as consumer prefer (by performance) or in a way that favours Amazon’s logistics services.

The European Commission case also demonstrates a view that the treatment of merchants was unfair in that Amazon’s own products were ranked higher than equivalent rivals and the Buy Box incentives were extremely sharp.

In other words, if a merchant did not get into the Buy Box (which required buying FBA), their sales dropped almost to zero, while their Amazon ranking may only have been very slightly lower than the winner’s rank.

Such a strong response becomes unfair to sellers if there is any bias or imprecision in the ranking. This concern for fairness is conceptually distinct from the competition, but is a feature of European antitrust enforcement.

However, the fairness element is not central to the argument of illegality in either case. Since a merchant will not use a logistics service that causes exclusion from the Buy Box, the Amazon policy linking FBA, Prime and the Buy Box has an exclusionary impact on rival logistics providers.

These policies prevent merchants from multihoming (offering their goods on multiple marketplaces), which in turn creates an unnecessary barrier to entry of rival marketplaces. The link to competition is fundamental.

And importantly, while the quality of current rivals may be poor, that does not invalidate this theory of harm. Under different rules logistics providers would have different incentives to invest. If a rival could serve merchants within the Amazon Prime programme, it would have the incentive to invest to improve its quality so that merchants would select it, and this would generate competition in logistics.

If the Amazon algorithm is, in fact, downgrading products that consumers prefer, this lowers the quality of the service and should cause consumers to switch to a rival store. If rival stores can more easily enter because rival logistics are available, then competition between merchants will improve.

If the Amazon algorithm only ranks products according to attributes valued by consumers – with no bias or distortion – competition among those merchants will intensify and consumers will benefit.

3.3 Remedies to protect competition in fulfilment

A simple remedy to apply in the United States would be the restoration of the Amazon SFP pro-gramme, which was shown to be technically feasible and popular with merchants (see section 4.1). Merchants would always be free to choose Amazon’s fulfilment service. It is likely Amazon would want to establish quality standards for rival delivery services to qualify for Prime, in order to maintain the reputation of the Amazon brand for quality and reliability.

Information reported in both the EU and US has shown that Amazon previously tracked such performance. Maintaining quality standards to ensure consumers have a good user experience is a perfectly procompetitive policy, provided the standards are transparent and are applied fairly. If so, a delivery service with a proven quality can be used by merchants in SFP, and their listings will be treated equivalently to those delivered by Amazon.

The European Commission has taken two approaches to a remedy. The prohibition decision was resolved with commitments that Amazon implemented in 2022 (Amazon, 2022):

To address the Buy Box concern, Amazon proposed to commit to:

–treat all sellers equally when ranking the offers for the purposes of the selection of the Buy Box winner;

–display a second competing offer to the Buy Box winner if there is a second offer from a different seller that is sufficiently differentiated from the first one on price and/or delivery. Both offers will display the same descriptive information and provide the same purchasing experience.

To address the Prime concerns Amazon proposed to commit to:

–set non-discriminatory conditions and criteria for the qualification of marketplace sellers and offers to Prime;

–allow Prime sellers to freely choose any carrier for their logistics and delivery services and negotiate terms directly with the carrier of their choice;

–not use any information obtained through Prime about the terms and performance of third-party carriers, for its own logistics services.”

Notice that the Buy Box rule in these commitments will be a less-effective replacement for an explicit MFN – as argued above – because it cannot steer users to less-expensive option as forcefully. The results of this combination of commitment and DMA ban will need to be studied to evaluate if the former weakens the latter.

4 The role of the DMA in promoting competition in ecommerce

4.1 DMA rules

One might think that Europe is ahead of the US in banning MFNs because Amazon gave up its MFN contracts in Europe in 2013 (Bundeskartellamt, 2013). But the US litigation evidence raises the possibility that the company effectively replicated the prohibition on sellers discounting off the Amazon platform by other means – and this could have been true in Europe as well.

It is therefore unclear whether the outcomes (prices and entry) Europe has experienced in the last ten years reflect competition effectively free of MFNs or not.

The European Digital Markets Act (Article 5(3)) again bans MFNs for the core platform services designated by the European Commission. Amazon’s retail business is a CPS and therefore must comply with Article 5(3) by March 2024. If the processes and algorithms described above are being used in Amazon’s European operations today, these will surely be viewed as violating the DMA and would have to be changed.

The DMA also explicitly permits disintermediation of the platform in Article 5(4). It says that gatekeepers, or the hard-to-avoid digital giants covered by the DMA:

“… shall allow business users, free of charge, to communicate and promote offers, including under different conditions, to end users acquired via its core platform service or through other channels, and to conclude contracts with those end users, regardless of whether, for that purpose, they use the core platform services of the gatekeeper.”

Juxtaposing this wording with text from Amazon’s Seller Code of Conduct in the US is informative7:

“Circumventing the Sales Process: You may not attempt to circumvent the Amazon sales process or divert Amazon customers to another website. This means that you may not provide links or messages that prompt users to visit any external website or complete a transaction elsewhere.”

Article 6(5) of the DMA requires gatekeepers to not rank their own services and products more favourably than those of third parties. This rule backs up, or duplicates, one of the Buy Box commitments and might affect Amazon’s house brands and retail products relative to the products of third-party sellers on Amazon Marketplace.

It also likely applies to Amazon’s Prime fulfilment and delivery service (FBA). FBA should not automatically be ranked favourably relative to services of third-party sellers, but rather the ranking conditions should be “transparent, fair and non-discriminatory.”

Amazon itself has the ability to measure how well SFP serves customers; it found that over 95 percent of the time, SFP met the delivery requirements set by Amazon (FTC ¶ 401). Under this rule, it would seem that a product delivered by a rival service that is as fast and reliable will cause the product to be ranked equivalently to one being delivered by Amazon Prime, all else being equal.

Importantly, in addition to Articles 5(3) and 5(4), the DMA also contains an anti-circumvention rule in Article 13. If Amazon devised methods to effectively replace the platform MFN contracts, they could be considered circumvention of 5(3) and 5(4).

Such an interpretation is sup-ported by statements in the FTC complaint against Amazon such as “replacement of a contractual price parity term with an expansion of SC-FOD would appear to be] not only trivial but a trick and an attempt to garner goodwill with policymakers amid increasing competition concerns” (FTC ¶ 15).

4.2 The effectiveness of the DMA

The Commission defined Amazon’s core platform service to be its marketplace services, not its retail services. Therefore, the de-facto MFN that operates through the retail channel, the Minimum Margin Agreement, may not be governed by the DMA.

The EU competition authority may want to bring an antitrust case against Amazon’s retail MFN under Article 102 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the EU (prohibiting abuse of dominance). In this way the antitrust law would complement the DMA and fill an enforcement gap. This package of enforcement outcomes such as price and quality in the EU e-commerce marketplace.

Rival e-commerce sites that do not require costly advertising and/or have lower participation fees will enable merchants to set lower prices there and attract consumers with those lower prices8. Because of the prohibition on MFNs, those merchants will not be penalised by Amazon for the price differential.

In a setting of unfettered competition we may see consumers leave Amazon in pursuit of lower prices, or we may see consumers choose to pay more for the quality they are accustomed to and stay with Amazon. Either outcome is a manifestation of competition. Business users will be free to set the prices they want on each distribution channel they use, and end users will therefore have more choice and lower prices.

DMA Article 13 prohibiting circumvention will play an important role in enforcement of the other Articles needed to create competition in e-commerce. Because it is clearly straightforward to create algorithms and policies that mimic the effect of a contractual MFN, enforcers will need to develop processes or tests to monitor compliance under DMA Article 5(3), or the ban on MFNs will achieve almost nothing.

Successful enforcement will advance the DMA’s contestability and fairness goals. The ban on MFNs increases contestability both on the platform and between platforms. Safeguarding merchants’ freedom to contract differently across distribution channels and the equitable ranking of offers enhances fairness between different business users, as well as between business users and the platform’s offerings.

5 Conclusions and policy recommendations

Soon there will be evidence of the effectiveness of the newly-mandated choice architecture of the Buy Box and its algorithm. Enforcers, merchants and Amazon will be able to measure the performance of third-party fulfilment and delivery, which will be very helpful to policy development. The changes should cause products without Prime shipping and lower prices to appear higher in the organic ranking, which could reduce the influence of Prime.

However, advertised products may fill the search results page so that shoppers do not see these highly-ranked inexpensive products. Such a poor user experience might cause consumers to shop elsewhere, and if the MFN provision (DMA Article 5(3)) is enforced, competitors to which consumers can switch will enter.

Even better, switching consumers can use their rights under DMA Article 6(9) to choose to port their personal data, including addresses, recurring purchases and methods of payment, to their new accounts with rivals.

Enforcers in the US should pursue a simple ban on platform MFNs because it will likely pre-serve competition between platforms with minimal negative impact. An effective remedy would also be to ban conduct and contracts similar to MFNs in Amazon’s retail business, such as the Minimum Margin contracts.

If all those contracts – and the establishment of any similar programme that achieves the same anticompetitive ends – are prohibited, price competition will be able to flourish online. Given the policies Amazon seems to have adopted to replace MFNs in practice, both elements of the remedy are crucial.

In Europe, the main enforcement challenge seems to be possibility of de-facto MFNs enforced through carefully designed algorithms. Amazon’s March 2024 compliance report to the European Commission may need to include information describing whether Amazon tracks the prices of its sellers on other platforms, and if it does, what actions Amazon takes after it finds sellers charging less outside Amazon’s marketplace.

The answers to these questions are critical to demonstrate the gatekeeper is in compliance with the DMA. The Commission may find the information revealed in the US litigation to be helpful as it interprets Amazon’s compliance reports, as well as in any Article 102 litigation.

The case of Amazon illustrates that different parts of the DMA can work together to create a whole that is greater than the list of those parts. Eliminating MFNs allows for lower prices on rival sites, while a consumer’s ability to port her data allows for easy switching to those sites.

Unbiased rankings allow the best choices to rise to the top of the search results page, including choices fulfilled by a rival logistics provider. That rival logistics provider in turn can support entry in e-commerce. And the entrant can attract customers with a differentiated strategy which cannot be blocked by incumbents using MFN-equivalent policies or practices. The addition of the Buy Box redesign adds to the force of this combination.

Making sure this cluster of policies is effective at increasing contestability and fairness will require measurement of outcomes as well as inputs. What choices appear in the Buy Box and how do consumers respond to different design choices in the shopping environment? Measurement of the performance of all parties providing fulfilment and logistics will likewise be critical to policy evaluation.

The more effective these European Commission enforcement changes are – the MFN enforcement, portability of data, the Buy Box design and the increased shipping options – the more likely it is that they will be exported to other jurisdictions facing similar problems, whether from Amazon or another local dominant e-commerce platform.

In the United States, third-party sellers and brands will want California and the FTC to demand the European solutions if they are shown to be successful. Litigation in the US moves so slowly that there will be plenty of time to evaluate the outcomes of the existing EU antitrust commitments and the DMA before any US remedy would need to be chosen.

Moreover, a judge would likely find it attractive to choose a remedy that reduces the possibility of negative unanticipated outcomes in the marketplace. A solution that has been tried in Europe and has succeeded there is much less risky to impose on US consumers.

Additionally, Amazon cannot argue that such a remedy is costly or difficult from an engineering point of view because the company will already have built and deployed it in Europe. But this cheerful picture depends on the effectiveness and success of the new European enforcement package.

Endnotes

1. See European Commission press release of 22 December 2022, ‘Antitrust: Commission accepts commitments by Amazon barring it from using marketplace seller data, and ensuring equal access to Buy Box and Prime’. The UK CMA has already agreed commitments (CMA, 2023). In addition, the Italian Competition Authority levied a substantial fine of more than €1 billion; see press release of 9 December 2021, ‘A528 – Italian Competition Authority: Amazon fined over € 1,128 billion for abusing its dominant position’.

2. See European Commission press release of 6 September 2023, ‘Digital Markets Act: Commission designates six gatekeepers’.

3. See for example Cooper (1986), Salop (1986), Scott Morton (1997), Moshary (2015) and Baker and Chevalier (2013).

4. Amazon Prime is a paid subscription service that gives certain premium benefits to customers, including faster delivery of goods and access to music and other services.

5. FTC ¶ 408. Amazon wanted to minimise any potential backlash from SFP sellers, so in 2019 Amazon let sellers already in SFP remain, while blocking new enrolment. Critically, Amazon communicated to those sellers who were already in SFP that it expected them to fulfil orders themselves, rather than using independent fulfilment providers. Amazon’s internal analyses showed that sellers using independent fulfilment ser-vices met Amazon’s stringent SFP standards more often than sellers fulfilling orders themselves. For example, in the last quarter before Amazon suspended enrolment, SFP sellers using independent fulfilment providers satisfied Amazon’s delivery requirement 98.4 percent of the time (compared to 96 percent for all SFP sellers), and satisfied Amazon’s shipping requirement 99.8 percent of the time (compared to 96.8 percent for all SFP sellers).

6. See footnote 1.

8. FTC ¶ 236. The FTC complaint quotes one Amazon executive as acknowledging that the advertising costs are “likely to be passed down to the customer and result in higher prices for customers”; Amazon founder Jeff Bezos is quoted as instructing executives to “accept more ‘defects’” (the term for junk advertisements) because the advertising revenue to Amazon is more than the sales it loses from the degradation in search quality and higher prices. See FTC ¶ 5.

References

Amazon (2022) ‘Case COMP/AT.40462 and Case COMP/AT.40703 – Amazon; Commitments to the European Commission’.

Baker, J and J Chevalier (2013) ‘The Competitive Consequences of Most-Favored-Nations Provisions’, Antitrust Magazine 27(2).

Baker, J and F Scott Morton (2018) ‘Antitrust Enforcement Against Platform MFNs’, Yale Law Journal 7(27): 1742-2203.

Bundeskartellamt (2013) ‘Amazon removes price parity obligation for retailers on its Marketplace platform’, Case Report.

CMA (2023) ‘Decision to accept binding commitments under the Competition Act 1998 from Amazon in relation to conduct on its UK online marketplace’, Case number 51184, Competition & Markets Authority.

Cooper, TE (1986) ‘Most-Favored-Customer Pricing and Tacit Collusion’, RAND Journal of Economics 17(3): 377-388

FTC (2023) ‘Federal Trade Commission and others v. Amazon.com, Inc.’.

Moshary, S (2015) ‘Advertising Market Distortions from a Most Favored Nation Clause for Political Campaigns’, mimeo.

Salop, SC (1986) ‘Practices that (Credibly) Facilitate Oligopoly Co-ordination’, in JE Stiglitz and GF Mathewson (eds) New Developments in Analysis of Market Structure, Palgrave Macmillan London

Scott Morton, F (1997) ‘The Strategic Response by Pharmaceutical Firms to the Medicaid Most-Favored-Customer Rules’, RAND Journal of Economics 28(2): 269-290.

Superior Court of the State of California (2022) ‘The People of the State of California v. Amazon.com, Inc.’.

Disclosure: Within the last three years the author has engaged in antitrust consulting for a range of healthcare companies, government plaintiffs and the digital platforms Amazon and Microsoft. The author’s Amazon engagement ended more than two years ago and predates the US complaints discussed in this article.

This article is based on the Bruegel Policy Brief Issue no 22/23 | December 2023.