Free trade remains the best policy

Patrick Minford is Professor of Applied Economics at Cardiff University

It has always been obvious to economists that the massive Trump tariff rollout in early April would be hugely damaging-to the US. Tariffs seem to many politicians to be a way of forcing foreigners to pay for their country’s exports, so making a gain for their voters; they also seem to think that by protecting their home industries they are scoring a gain in higher home output.

Unfortunately, in the world markets where trade takes place, none of this is true. In fact the opposite is true; the cost of tariffs on imports is paid by home consumers, while the rise in home output in the protected industries causes the contraction of more efficient unprotected industries, which lowers overall output.

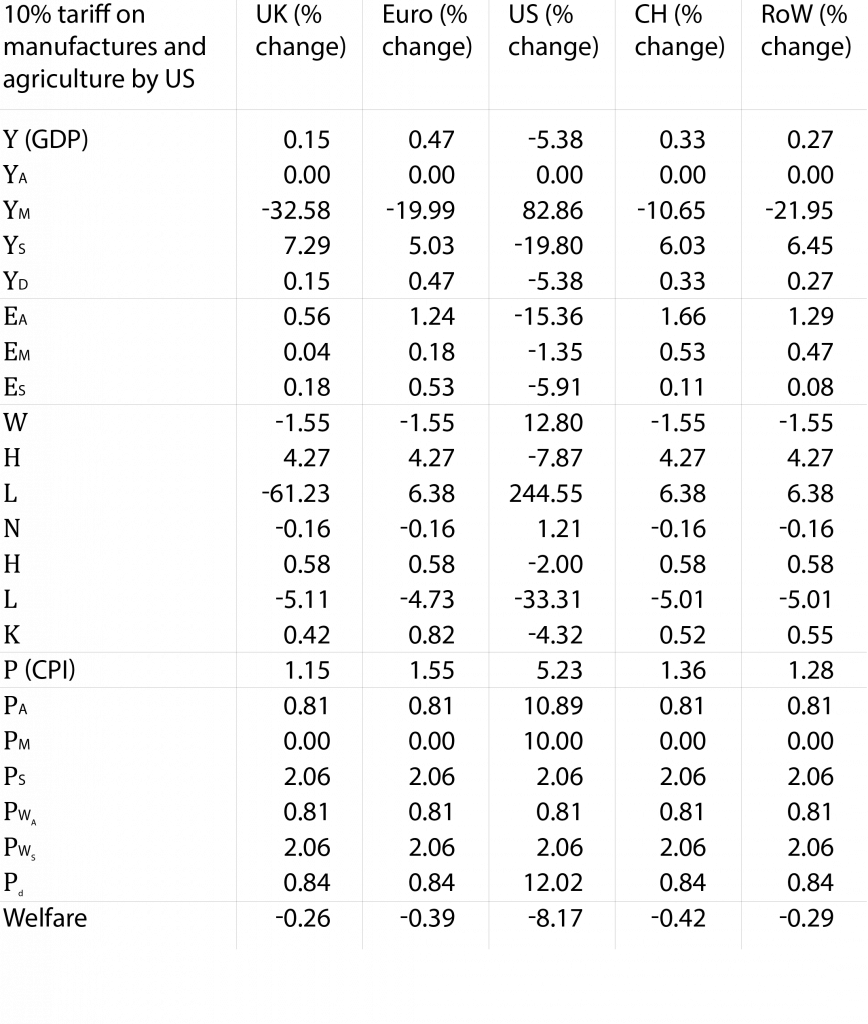

Table 1 shows what happens with a 10% US tariff according to our world trade model; we use the model that fits best-the ’Classical’ model, which assumes that world markets act in a highly competitive manner. What the tariff does is cause a loss of welfare for the US of around 8% of GDP*.

Roughly half of this is due to reduced output as resources leave the most productive sectors and move into less productive protected ones. The other half is due to consumer welfare losses from higher prices. Now that US average post-deal tariffs have reached 17%, the implied US costs are up to 13% of GDP. As for other countries the costs are minimal; this is because they can all divert their exports to other parts of the world market.

Table 1. World trade model simulation of 10% tariff by the US on agriculture and manufactures imported from all other countries/blocs

Notation: y=output; E=Expenditure; N= unskilled labour force (w=its wages); H- skilled labour force (h=its wages); L=land (l= land price); K=capital; Pw=world price (world price of manufactures is numeraire); subscripts-A=agriculture; M=manufacturing; S=services; D=non-traded

Note on welfare measure: Welfare loss from the tariff is computed as: [Welfare percent =% output loss/GDP+consumer surplus lost-Terms of Trade gain- gain as % of GDP], where the consumer surplus loss=percent rise in CPI x 0.5 and the TOT gain=% rise in world price of exports/world price of imports x share of trade in GDP.

These are the long run costs. More immediately we also see short run effects causing lost output both in the US and abroad and raising US inflation as the tariffs raise prices.

It may appear as if President Trump has got away with his tariff policies in spite of these and other criticisms from economists like us. But in the short run exporters to the US may be willing to absorb some of the tariff cost to keep the US market until they can divert their exports elsewhere at the better prices available in world markets.

This will keep US prices down for a while. But once they have diverted their output to other world markets paying the normal world price, they will charge the same prices to US importers. So the US inflation hit will come through.

As for output, in the short run it depends on demand. So US demand will be set by US monetary and fiscal policies, which are likely to be expansionary. Similarly foreign demand will be set by the equivalent foreign policies, especially in Europe and China.

But these are likely to offset the deflationary tariff effects only partially, as fiscal deficits are high and interest rates already lowered. We have yet to see how the world economy settles down in the short run as the tariff fog disperses. But in the long run output depends on supply. With the tariff raising the US prices of home manufactured output, manufacturing will expand as resources are switched from services, which give the US its comparative advantage and so are more productive. Hence overall output will fall.

What these figures underline is the self-harm from tariffs, explaining why most other countries have been reluctant to retaliate by raising their own tariffs. The exception was China for which the short run effects were highly threatening, given its huge excess capacity in its chosen and highly subsidised hi-tech sectors like EVs and batteries.

By retaliating with tariffs on the US only, it avoids the long run tariff costs as its consumers simply switch to non-US products so that import prices remain unchanged.

However, China’s economy is slowing as its excess capacity is hard to divert to other countries, now resisting dumping, and its home policies are unable to offset home deflation due to the collapse in property and the loss of consumer confidence. In Europe generally public debt is high and limiting the scope for fiscal stimulus, while monetary policy has already eased as much as may be possible given the need to keep inflation down.

It is these short run problems with US tariffs that create the temptation to retaliate. In the interwar period, there was general retaliation as countries tried to protect the demand for their home industries in the face of falling export demand. So far retaliation has been the exception rather than the rule; China has retaliated against the US only but with the US targeting other parts of SE Asia to which China exports, this restriction may not last.

What this all means is that the US is damaging its long run prospects by pursuing old-fashioned protectionism, and the rest of the world will be reducing its US trade. US and world growth will probably be slower in the short run, as further policy loosening is difficult.

However, it is worth spelling out why free trade has been the best policy for the US as well as the world at large. Even as the US has now contracted out of trade, the rest of the world will need to rebuild the world trade order without it and not be tempted to join in a general trade war.

In the long run protection by the US alone will not affect the rest of the world and can be ignored, so that merely US trade collapses. This will permit the rest of the world to rebuild the world trading system until the US once more rejoins it at some future date

Why globalisation and free trade is good for the common man-the disastrous mistake of Trump has been to fail to see this and other countries must avoid the same trap

It is widely said that today’s ‘populist’ agendas include the rejection of ‘globalisation’ and ‘free trade’ in favour of ‘nationalism’ and protectionism. Certainly it is true that the Trump agenda did include these. Yet this agenda is a disaster for the US common man who voted for it, as we saw above. As for the rest of the world, it should strongly resist being sucked into a trade war and must maintain free trade.

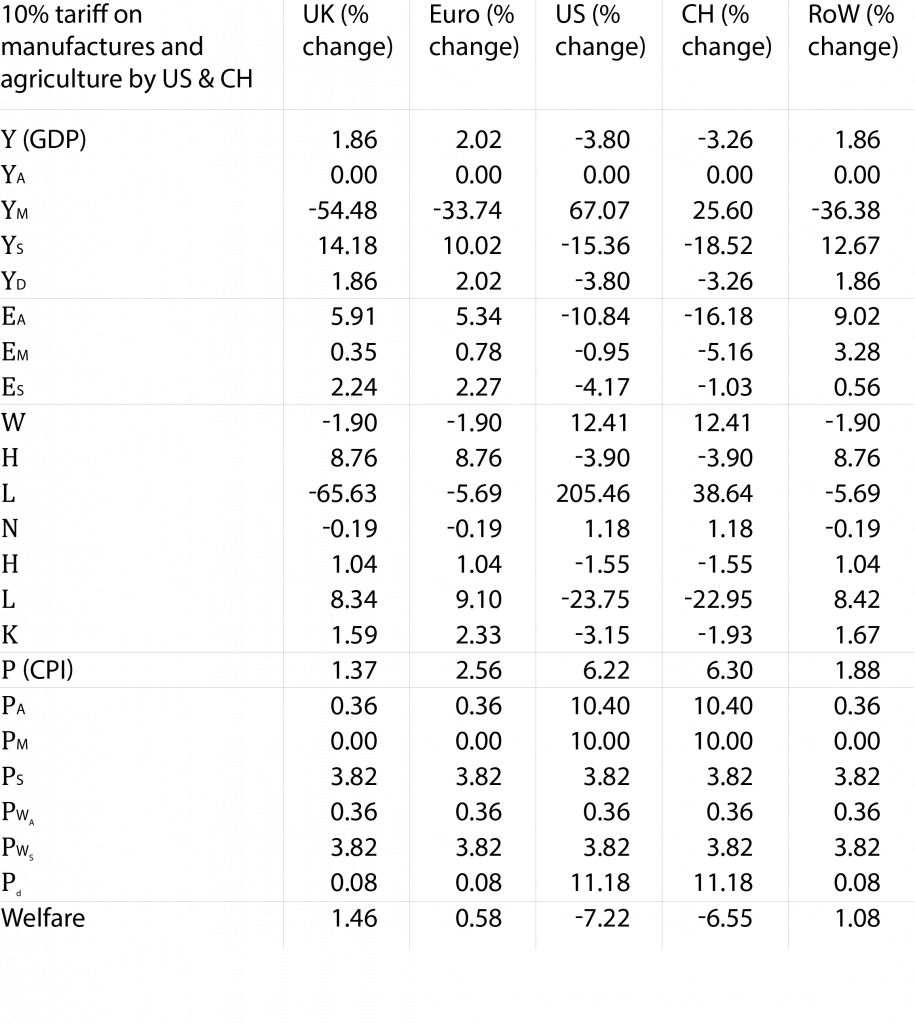

We illustrate why China should not retaliate with Table 2 showing the effect of China raising its tariffs in the same way as the US in retaliation. It shows the same self-harming effects as the US move.

In China’s case welfare falls by 7%, with about 3% coming from the fall in output and the rest from consumer welfare due to higher prices. Again the effect on other countries is small. This US-China tariff war only badly damages those two countries, the damage in each case coming from self-harm. It does seem now that both countries are discovering this and gradually retreating to a lowering of these tariffs.

Notice that in fact China has at no stage put a tariff on others than the US; but if it did, it would have no long run effect on them, as they would all divert their exports elsewhere. The main gain for them from this Chinese policy is that there are no short run demand effects coming from China.

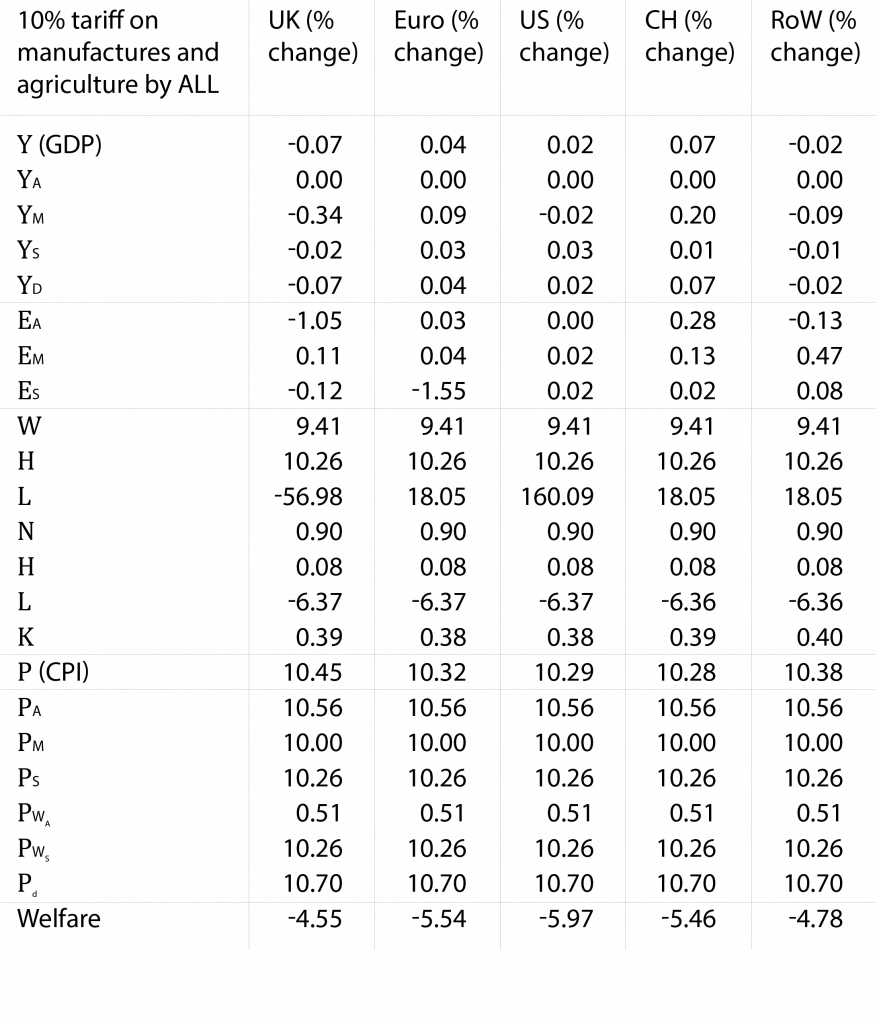

What this underlines is, as already noted, that other countries should not retaliate with their own tariffs, since this will only reduce their welfare further. To illustrate this (Table 3), we show the effects of a general application of 10% tariffs to all goods (manufactures and agriculture) from all other countries.

Now all countries are raising their goods prices internally by 10%, causing an initial world-wide shift of output into goods from services and of demand from goods into services.

However, this creates world excess demand for services which must be resolved by a rise in world service prices to eliminate these shifts in supply and demand. The overall result is a general rise in prices, damaging consumer welfare through the loss of surplus.

Notice that all these prices are expressed relative to the baseline world price of manufactures, which is kept fixed equal to 1, as the ‘numeraire’, so assuming zero inflation which the model does not calculate. Thus in this simulation the price of consumer goods rises by about 10% relative to consumer incomes, reducing the real value of consumption and losing half of this as surplus.

Table 2. World trade model simulation of 10% tariff by the US and China on agriculture and manufactures imported from all other countries/blocs

Notation: y=output; E=Expenditure; N=unskilled labour force (w=its wages); H-skilled labour force (h=its wages); L=land (l= land price); K=capital; Pw=world price (world price of manufactures is numeraire); subscripts- A=agriculture; M=manufacturing; S=services; D=non-traded.

Table 3. World trade model simulation of 10% tariff by all trade blocs on agriculture and manufactures

Notation: y=output; E=Expenditure; N= unskilled labour force (w=its wages); H-skilled labour force (h=its wages);L=land (l= land price); K=capital; Pw=world price (world price of manufactures is numeraire); subscripts-A=agriculture; M=manufacturing; S=services; D=non-traded.

Note on welfare measure: Welfare loss from the tariff is computed as: [Welfare percent=% output loss/GDP+consumer surplus lost-Terms of Trade gain- gain as % of GDP], where the consumer surplus loss=percent rise in CPI x 0.5 and the TOT gain=% rise in world price of exports/world price of imports x share of trade in GDP.

Conclusions

What all this shows is that globalisation and free trade are good for the economy and the average voter. Unfortunately, ignorant and ambitious politicians have tried, often successfully, to persuade this voter that he/she has been unfairly treated by the market forces these have unleashed, that they have been ‘left behind’.

Yet take for example American households: they have benefited from one of the fastest per capita growth rates in the OECD. While some industries have contracted, such as coalmining in West Virginia, the West Virginian residents like other voters displaced by global competition have enjoyed the massive expansion of Medicaid, Medicare and Social Security paid for by the economy’s growth and resulting tax revenues.

By contrast the Trump agenda, notionally designed to benefit the ‘left behind’, is causing them acute harm, both in the short and the long term, as our tables reveal.

It is vital that the rest of the world refuses to retaliate against this US trade-destroying agenda. The temptation is there to retaliate to prevent the short run effects of export disruption and reduced demand from the US-just as happened in the 1930s.

But in the long run protection by the US alone will not affect the rest of the world and can be ignored, so that merely US trade collapses. This will permit the rest of the world to rebuild the world trading system until the US once more rejoins it at some future date.

* Details of this model-fitting exercise can be found in Minford, P, Xu, Y and Dong, X (2023) ‘Testing competing world trade models against the facts of world trade’, Journal of International Money and Finance, 2023, vol. 138, issue C.