Balancing profit shifting and investment

Katarzyna Bilicka, Michael Devereux and Irem Güçeri

President Trump’s second-term tax agenda has already reshaped the global fiscal landscape – most notably through the passage of the ‘One Big Beautiful Bill Act’ (OBBBA) and a sharp, if legally contested, escalation in tariff use.

But arguably the most consequential change for the structure of the international tax system has been his decision to withdraw the US from the multilateral agreement, negotiated by more than 140 countries under the OECD’s Inclusive Framework, to introduce a 15% global minimum tax (GMT) on multinational enterprises (MNEs).

The GMT represents the most ambitious international effort in decades to curb profit shifting to tax havens. At the time of writing, 57 countries have already implemented measures to introduce the tax, and ten more have implementation in progress1.

But what, exactly, is at stake – for countries which have introduced the GMT, and for those that have not? How much profit shifting actually occurs? How is real activity affected by taxation, and how does that change when multinationals move paper profits across borders? And how costly are the elaborate tax-avoidance structures that make such shifting possible?

Economists have long debated the magnitude of profit shifting. Empirical estimates date back to Hines and Rice’s (1994) work that assumed that the more an MNE grows its profit shifting activities, the more and more costly it becomes to shift the next dollar of profit to tax havens.

Meta-analyses of firm-level studies (Beer et al 2019, Heckemeyer and Overesch 2017) suggest that reported taxable profits fall by a little over 1% when the tax rate rises by one percentage point – a modest semi-elasticity. Yet macroeconomic analyses using country-level data (Clausing 2016, Tørsløv et al 2022) find far larger responses. Why do the two literatures disagree?

Our recent research (Bilicka et al 2025) helps resolve this puzzle by identifying what has been missing from firm-level studies, namely, a more realistic treatment of global MNEs’ tax avoidance practices and acknowledging the large number of multinationals that shift all their profits out of high-tax countries.

These ‘full shifters’ behave fundamentally differently from firms that shift only part of their profits and ignoring them systematically understates the true scale of profit shifting by roughly half.

Treating tax avoidance as an investment

To explore this behaviour, we build a structural model in which each multinational decides not only how much capital to invest in each country, but also how much to invest in a tax-avoidance asset: the firm’s internal capability to move profits to low-tax locations. This ‘tax avoidance asset’ acts as a public good within the multinational: once established, it reduces the variable cost of shifting profit for all subsidiaries worldwide.

The idea reflects companies’ real-life policy choices. A company that owns valuable intellectual property might establish a cost-sharing agreement that allocates patent ownership to its Caribbean affiliate. Setting up such an arrangement might be expensive, but once in place, the marginal cost of routing income through that structure is small.

Firms without such capacity face much higher marginal costs and may remain taxable in high-rate countries. Recognising the initial investment into avoidance and its impact on the variable profit-shifting cost changes the predicted responses to tax reforms.

Quantifying fixed and variable costs of profit shifting

Our study distinguishes between fixed and variable costs of profit shifting. Using corporate tax return data from the UK, we estimate that the fixed costs (of setting up the structure) are 1.5% of the true tax base. The variable costs (maintaining it and shifting each additional pound) add another 3%.

These costs vary across firms depending on their business models and opportunities for shifting. For firms with low costs, full shifting is optimal. For others, partial shifting makes sense. And for some, the costs outweigh the benefits entirely. These estimates highlight the significant resources MNEs allocate to tax avoidance – lawyers, transfer-pricing specialists, and complex intra-group arrangements.

Why focusing only on the ‘intensive margin’ misses half the story

The standard economic model of profit shifting treats avoidance as a smooth, continuous response: a firm shifts a little more profit when tax differentials widen. Empirical studies using microdata typically estimate this relationship by regressing reported profits on tax rates, implicitly assuming that every firm adjusts at the margin.

In practice, however, many firms report zero taxable profits year after year. There are, of course, business-as-usual reasons for such patterns alongside profit shifting, including true company losses that can be carried over to multiple tax periods.

But even when we account for these ‘true’ losses, there remains a substantial share of MNEs reporting zero taxable profits persistently. This is because, once a multinational has established the structure that allows them to move profits to low-tax jurisdictions, the marginal cost of shifting an additional dollar may be small.

This pattern – some firms shifting intensively, others completely – creates a wedge between micro-level and macro-level estimates of the semi-elasticity of profit shifting. The latter capture both the intensive response among partial shifters and the extensive decision to exit the tax base entirely. Our goal was to model both margins jointly and quantify the underlying costs that generate such heterogeneity.

Recognising the importance of extensive margin helps reconcile conflicting evidence, explains why multinationals respond so strongly to tax changes in aggregate, and clarifies the true trade-offs facing policymakers as they reshape international taxation for the 21st century

Reconciling divergent elasticities: micro versus macro perspectives

The model reconciles the conflicting evidence from previous studies. Using UK tax data, we estimate that a one percentage point increase in the tax rate reduces reported profits by 2.4%. This matches the range of ‘macro’ estimates, which typically find elasticities of between 2.5 and 5.2 (Clausing 2016, Hines and Rice 1994).

But if we replicate the approach of typical firm-level studies – focusing only on firms with positive taxable income – we get an elasticity of just 1.3, closely matching the consensus from micro studies of around 1.1 to 1.4 (Beer et al 2019, Heckemeyer and Overesch 2017). The gap therefore stems from ignoring firms that have exited the tax base altogether.

The investment trade-off

Profit shifting doesn’t just affect tax revenues – it fundamentally alters investment incentives. Our model recognises that profit shifting reduces the effective tax rate on capital, and so in turn reduces the cost of capital for investment in real productive assets.

As a result, multinationals that engage in aggressive profit shifting respond much less to statutory tax rate changes when making investment decisions. A one percentage point tax increase reduces their capital investment by just 0.8%.

Firms that don’t shift profits respond more than twice as strongly, cutting investment by 1.8%. This happens because profit shifting dampens the tax impact, keeping the effective tax rate low even when statutory rates rise.

Policies that successfully curb profit shifting will raise the effective tax rate multinationals face, potentially reducing investment. We gain revenue and reduce wasteful avoidance costs, but at the price of higher costs of capital and potentially lower investment.

Lessons from the Italian CFC reform

We test our model through a quasi-natural experiment: the 2002 Italian Controlled Foreign Company (CFC) reform, which tightened rules on profit shifting to tax havens. CFC rules operate, for the purpose of our model, in a very similar way to the way in which current minimum tax rules work.

Using a difference-in-differences approach, we find that the reform significantly reduced profit shifting by Italian MNEs operating in the UK. This led to higher reported UK taxable income but had limited short-term effects on investment. These results align with our model’s prediction that curbing profit shifting increases the cost of capital for productive assets, potentially dampening investment in the long run.

Policy experiments highlight trade-offs in tax reform

Our framework also allows us to conduct counterfactual analyses of tax policy scenarios, offering insights into the trade-offs faced by governments:

Reducing high-rax country rates. Lowering corporate tax rates in high-tax jurisdictions reduces the incentive for firms to shift profits abroad, leading to increased domestic investment. This comes at the expense of tax revenue collected domestically.

Increasing tax haven rates or introducing a global minimum tax. Raising tax rates in havens curbs profit shifting but may also deter investment in high-tax countries due to higher capital costs. For example, a 15% GMT significantly reduces profit shifting and the wasteful investments associated with tax avoidance networks. This raises global welfare for relatively low rates of GMT such as the currently agreed 15%. But global welfare declines with higher GMT rates due to distortive effects of the tax on investment.

Our findings highlight that the optimal tax policy depends on balancing these trade-offs. For instance, while a GMT creates revenue gains by discouraging profit shifting, its broader impact on productive investment varies across countries.

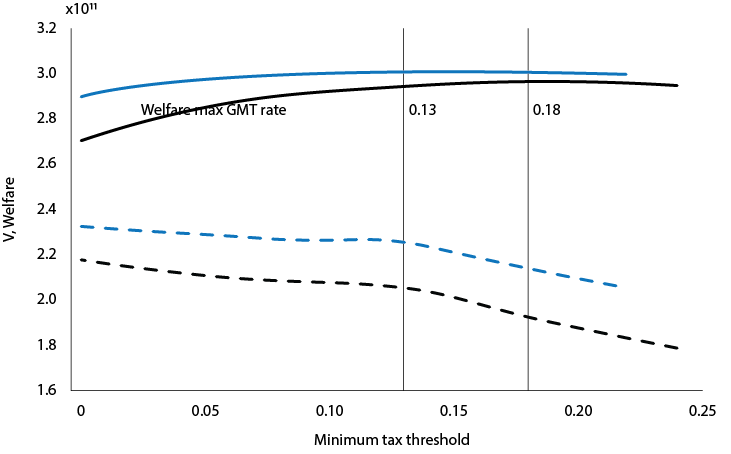

In Figure 1, we demonstrate that there are efficiency gains from introducing a GMT at moderate levels, and that the optimal rate varies depending on the implementing high-tax country’s own tax rate. The initial gains for low levels of GMT thresholds arise from the elimination of costly tax avoidance investments. The dashed lines in the figure show the net present value of MNE cash flows (denoted V) and the smooth lines indicate global welfare.

Based on our simple measure of welfare as a tax revenue-investment trade-off, for a country with a 30% home corporate tax rate (the black lines), the optimal GMT rate is 18%, while this rate is 13% for a country with a 20% home corporate tax rate (the blue lines).

Figure 1. Impact of global minimum tax at varying threshold rates on welfare

What this means for policy

As countries implement the global minimum tax and debate further reforms, two lessons emerge. First, the scale of profit shifting may be larger than many firm-level studies suggest – perhaps twice as large – and revenue projections based solely on intensive-margin responses will be too conservative.

Second, the connection between profit shifting and investment creates fundamental trade-offs that cannot be ignored. In implementing policies aimed at eliminating profit shifting, policymakers need to balance revenue needs, efficiency gains from reduced avoidance costs, and the effects on real economic activity.

Recognising the importance of extensive margin helps reconcile conflicting evidence, explains why multinationals respond so strongly to tax changes in aggregate, and clarifies the true trade-offs facing policymakers as they reshape international taxation for the 21st century.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Katarzyna Bilicka is a Lars Peter Hansen Associate Professor of Economics and Statistics in the Jon M Huntsman School of Business at Utah State University, Michael P Devereux is Emeritus Director of the Oxford University Centre for Business Taxation, Emeritus Professor of Business Taxation at Saïd Business School, and an Emeritus Fellow at Oriel College, and Irem Güçeri is an Associate Professor of Economics and Public Policy in the Blavatnik School of Government at the University of Oxford

Endnote

1. See the PwC Pillar 2 Tracker at https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/services/tax/pillar-two-readiness/country-tracker.html.

References

Beer, S, R De Mooij and L Liu (2020), “International Corporate Tax Avoidance: A Review of the Channels, Magnitudes, and Blind Spots”, Journal of Economic Surveys 34(3): 660-88.

Bilicka, K, M Devereux and İ Güçeri (2025), “Tax Policy, Investment and Profit Shifting”, NBER Working Paper 33132.

Clausing, K (2016), “The Effect of Profit Shifting on the Corporate Tax Base in the United States and Beyond”, National Tax Journal 68(4): 905-934.

Heckemeyer, JH and M Overesch (2017), “Multinationals’ profit response to tax differentials: Effect size and shifting channels”, Canadian Journal of Economics/Revue canadienne d’économique 50: 965-994.

Hines, J and E Rice (1994), “Fiscal Paradise: Foreign Tax Havens and American Business”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 109(1): 149-182.

OECD (2020), Tax Challenges Arising from Digitalisation – Report on Pillar Two Blueprint: Inclusive Framework on BEPS, OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project, OECD Publishing.

Tørsløv, T, L Wier, and G Zucman (2022), “The Missing Profits of Nations”, Review of Economic Studies 90(3): 1499-1534.

This article was originally published on VoxEU.org.