Assessing China’s efforts to increase self-reliance

Francois de Soyres is Principal Economist and Dylan Moore is a Research Assistant at the Federal Reserve Board of Governors

Since the beginning of 2018, the US and China have been increasing tariff rates on each other’s imports, spurring debates about a possible fragmentation of trade into blocs of aligned countries (Alfaro and Chor 2023, Utar et al 2023, Pierce and Yu 2023).

Later that year, in a November 2018 speech, President Xi Jinping mentioned that current events were forcing China to “travel the road of self-reliance.” This vow has been forcefully reaffirmed in a variety of public official communications. More recently, at the closing ceremony of the 2023 National People’s Congress, Xi insisted that “China should work to achieve greater self-reliance,” referring to tensions with the US and other democracies.

In this column, we investigate the extent to which China is making progress towards self-reliance. We start by briefly reviewing China’s growth model, which is based on strong investment to expand production capacity coupled with restrained domestic consumption.

Then, we show that the Chinese economy is gradually becoming less dependent on imports, with stark trends in key manufacturing and technology sectors. A particular focus on the automotive sector highlights the impressive pace at which China went from a net importer to a net exporter of finished cars, together with expanding its share of value added in production.

We conclude by discussing the recent sharp decrease in inward foreign direct investment (FDI) in China and the risk of a gradual decoupling of production between China and advanced economies.

China’s declining reliance on imports, particularly in critical sectors like high tech and electrical products, demonstrates the progress that the country has made in just a few years

China’s growth model

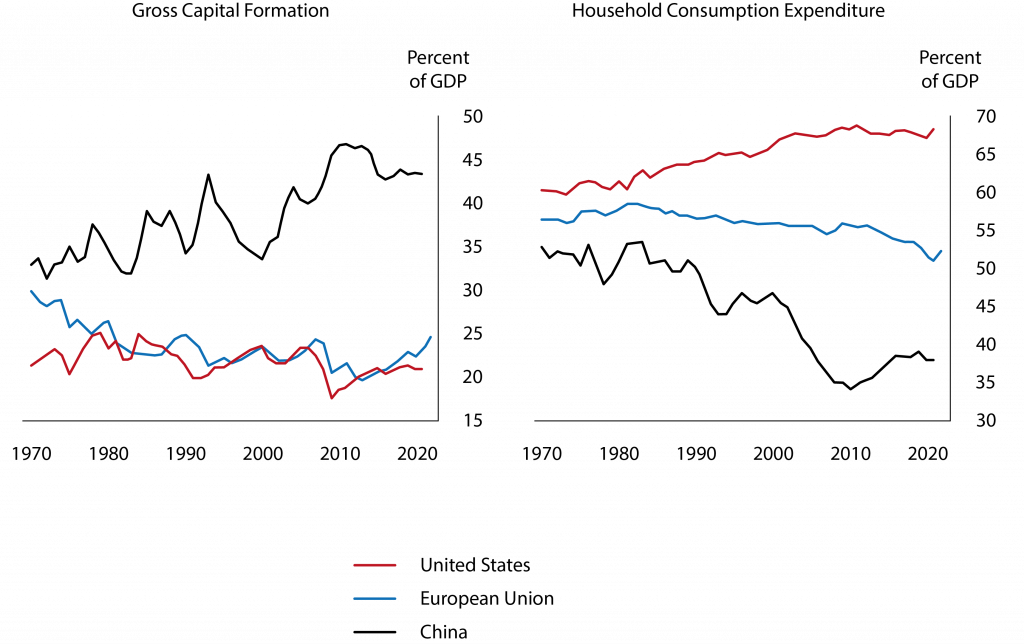

Over the past five decades, China’s development model has been characterised by an increasingly high investment share of GDP (left panel, Figure 1) together with a strikingly low household consumption share of GDP (right panel, Figure 1).

As China expanded its production capacity, especially in manufacturing sectors, without a corresponding increase in domestic demand, its economy became dependent on foreign demand.

According to data from the International Monetary Fund, China’s goods trade surplus reached an all-time high in 2022 of almost $900 billion, illustrating how much China relies on foreign demand as an engine of growth.

While the export-dependency of the Chinese economy has been widely discussed (Bown 2022, Freund et al 2023, Hogan and Hufbauer 2023), Chinese authorities have been more worried about the country’s import-dependency, observing that China needs access to a variety of inputs for its own production.

In 2018, President Xi Jinping called for a ‘whole-nation approach’ to reducing China’s dependence on imports of critical technology components. His strategy includes increasing the country’s investment in strategically critical technology sectors, strengthening domestic talent-grooming, and ‘reshoring’ expertise to spearhead innovation.

Figure 1. Composition of Chinese growth in China

Note: The data extend through 2021 for China and the US and 2022 for the EU.

Source: The World Bank.

Decline of China’s reliance on imports

We start by looking at the joint evolution of GDP, imports, and exports. While imports and exports have historically been much more volatile than official GDP numbers, Figure 2 reveals another remarkable fact: over the past five years, import growth has been notably weaker than export growth.

Figure 2. Evolution of Chinese GDP versus trade

Note: Series are seasonally adjusted.

Source: Haver Analytics; FRB staff calculations.

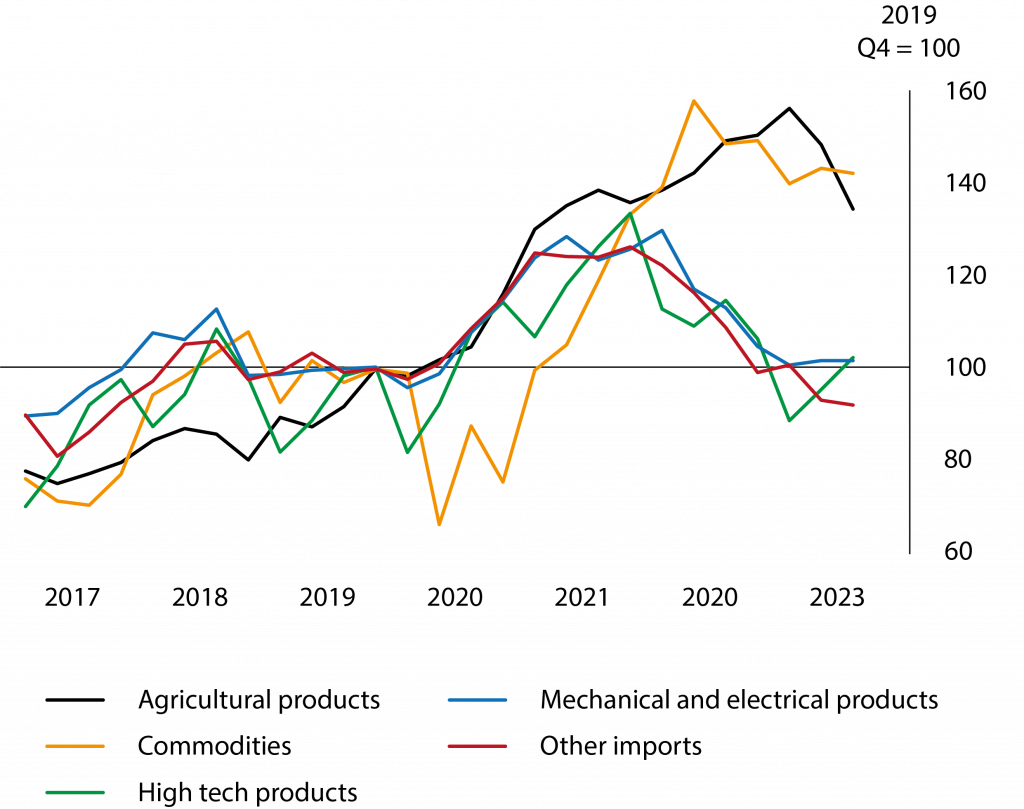

Taking a closer look at the sectoral level, we note that the lukewarm Chinese imports are mostly driven by two sectors: (i) Mechanical & Electrical products and (ii) High-Tech products, which having been falling since early 2022 (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Evolution of Chinese imports by sector

Note: Data are seasonally adjusted and end in 2023:Q3. Commodities includes coal and lignite, crude oil, refined petroleum products, fertilizers, steel or iron products, unwrought copper and copper, and unwrought aluminium and aluminium. Other imports includes beauty cosmetics and toiletries, plastics in primary forms, textile yarns, fabrics, and their products, and garments and clothing accessories. Share of total imports: 35% mechanical and electrical products, 23% high tech products, 18% commodities, 10% agricultural products, 3% other imports, 2% medicinal materials and pharmaceutical products (not shown).

Source: Haver Analytics.

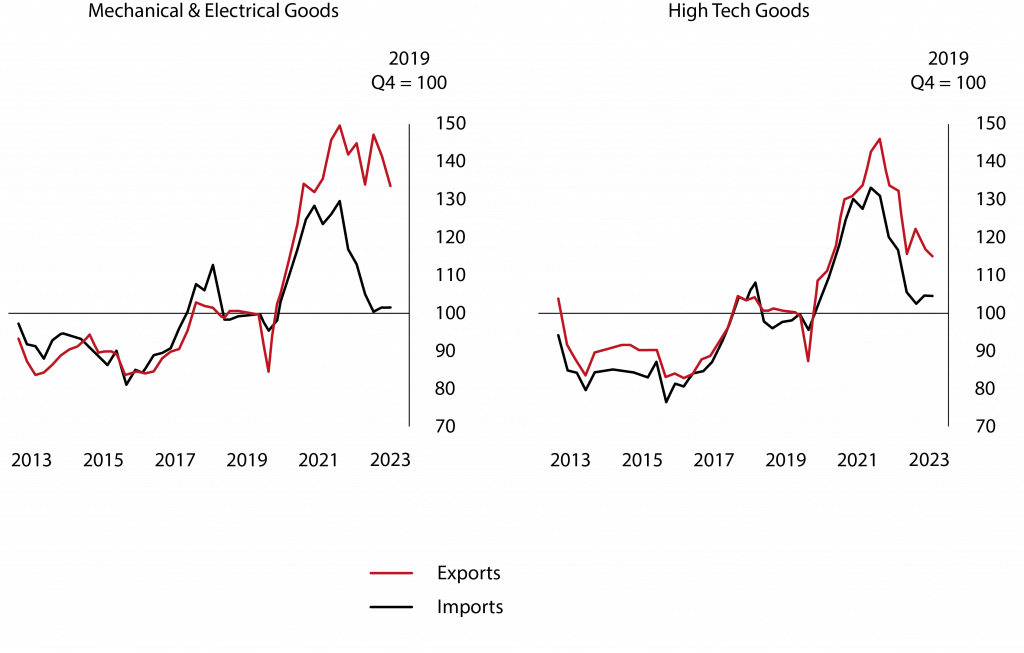

To investigate if the decrease in imports in these sectors could be driven by global forces, it is useful to look at the joint evolution of both imports and exports. Figure 4 reveals that imports and exports in these key sectors have decoupled since 2021, following a period in which the two measures moved closely together.

Mechanical and electrical product exports have been relatively flat, while imports have experienced a significant decline. Over the same period, high tech goods exports have declined, but imports have dropped further. The overall decline in high-tech trade is likely partially attributable to trade and investment restrictions imposed by the US in this specific sector.

Figure 4. Chinese trade balance by sector

Note: Data are seasonally adjusted and end in 2023:Q3.

Source: Haver Analytics.

A focus on the automotive sector

The Chinese automotive sector provides insights into the processes underlying China’s pursuit of self-reliance. China has received attention as the world’s biggest producer of electric vehicles (EVs), and EVs are one of the many high-tech products the government is interested in supporting.

However, Chinese exports of all automobiles – including internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles – have surged since 2020, greatly outpacing overall production and domestic sales due to several factors (Figure 5, left panel).

First, China can produce cheaper cars due to lower domestic prices for components like steel and electronics. Local governments have also been providing subsidies, particularly to electric vehicle companies, further pushing down prices in the sector.

Second, Chinese domestic auto demand has shifted strongly towards electric vehicles (Figure 5, right panel), leaving China with a large production capacity for internal combustion engine cars at a time of diminishing domestic demand for these vehicles.

This has pushed China to export markets, where demand for internal combustion engine cars is not declining as rapidly, rather than closing these factories entirely.

Figure 5. Shifting trends in the Chinese automotive industry

Note: New energy vehicles is the term used by the Chinese government for vehicles that are predominantly powered by electricity.

Source: Haver Analytics.

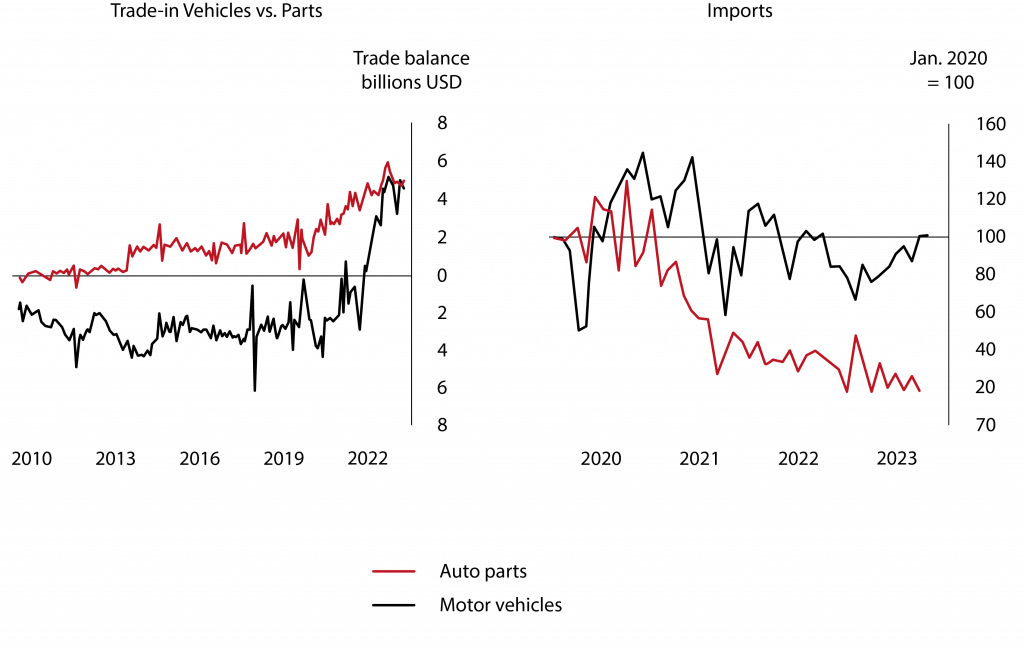

Moreover, Figure 6 (left panel) shows that China’s trade balance has experienced an impressive shift. For finished vehicles, China went from a net importer to a net exporter over the past few years, while at the same time significantly increasing its net exports of auto parts.

This supports the idea that China is not only gaining market shares in assembled vehicles but is also making progress towards comprehensive self-reliance.

Moreover, looking at gross flows reveals that the shift in the trade balance is the result of growth in exports but also a steep decline in imports, particularly auto parts (Figure 6, right panel).

Figure 6. Evolution of trade in auto parts and motor vehicles

Source: Haver Analytics.

Declining inward foreign direct investments

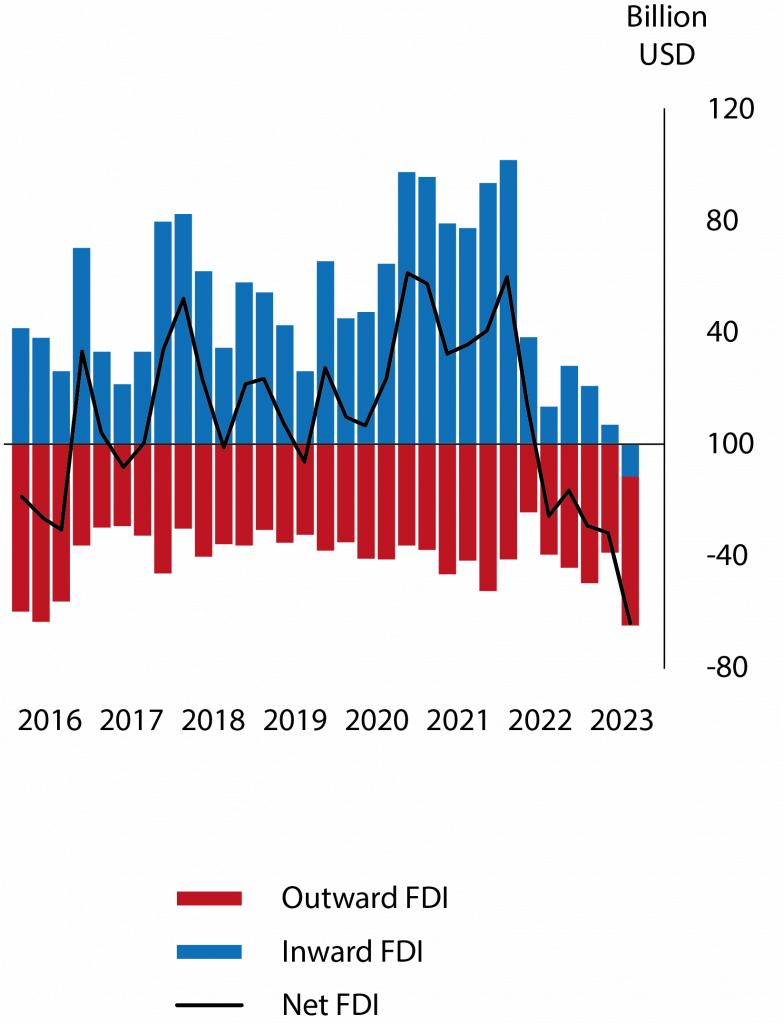

Declining foreign direct investment (FDI) into China may be affecting the country’s decision to pursue self-reliance, and its urgency in meeting these goals. As shown in Figure 7, inward FDI in China turned negative in 2023:Q3 for the first time since the value began being recorded in 19981. By comparison, outward FDI has maintained a relatively flat level since 2017.

Figure 7. Foreign direct investment in China

Source: State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE).

Some of this decline in inward FDI may be attributable to unique domestic factors in China, such as lower interest rates, a precarious real estate sector, and a crackdown on consulting firms through a counter-espionage law.

That said, on top of these economic forces, the rise in geopolitical risks and fear of sanctions is likely to have played an important role as well: tensions between the US and China have escalated over the past year, with the US even implementing a ban on high-tech investment in China in August.

As a result, global investors may have been directing part of their capital towards countries that are perceived as friendlier to the western bloc.

China’s pursuit of self-reliance may be both a cause and a consequence of the sharp decline in inward FDI. China has implemented several policies in the name of national security that have made it more difficult for foreign firms to succeed. At the same time, steep declines in investment could increase China’s urgency in reducing its foreign dependence.

Concluding thoughts

Since 2018, China has pursued its clear, stated objective of self-reliance, and seems to have made progress in several key sectors. As geopolitical tensions rise, domestic and foreign restrictions on crossborder trade and investment have also intensified, potentially increasing China’s urgency in pursuing its self-reliance goals.

China’s declining reliance on imports, particularly in critical sectors like high tech and electrical products, demonstrates the progress that the country has made in just a few years.

At the same time, production linkages between China and the western bloc remain high. According to the OECD, China’s contribution to foreign value added in world domestic final demand has grown significantly throughout the 2010s, reaching 39% in 2020.

A fragmentation of global production processes is not in sight, and China’s pursuit of self-reliance is likely to continue having global ramifications.

Endnote

1. A negative value for inward FDI means that foreigners are pulling money out of firms in China or selling off ownership stakes, or both.

References

Alfaro, L and D Chor (2023), “A perspective on the great reallocation of global supply chains”, VoxEU.org, 28 September.

Bown, C (2022), “Four Years Into the Trade War, are the US and China Decoupling”, Working paper, Peterson Institute for International Economics.

Freund, C, A Mattoo, A Mulabdic and M Ruta (2023), “US-China decoupling: Rhetoric and reality”, VoxEU.org, 31 August.

Hogan, M and GC Hufbauer (2023), “Despite disruptions, US-China trade is likely to grow”, Peterson Institute for International Economics Policy Brief 23-14, October.

Pierce, JR and D Yu (2023), “Assessing the Extent of Trade Fragmentation”, FEDS Notes, Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, November.

Utar, H, A Cebreros and L Torres (2023), “Shifting sands in cross-border supply chains: How Mexico emerged as a key player in the US-China trade war”, VoxEU.org, 9 December.

Authors’ Note: The views expressed in this note are our own, and do not represent the views of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve, nor any other person associated with the Federal Reserve System. This article was originally published on VoxEU.org.