What is a just transition and how does it affect the financial sector?

Ivana Popovic is a Research Associate, Alexandre C Köberle an Honorary Research Fellow, and Michael Wilkins is the Executive Director, at CCFI and Imperial College London’s Grantham Institute

1. Introduction

The concept of a just transition integrates social and environmental concerns related to a net zero transition. It stems from the fact that, although climate change is an environmental issue, it will unavoidably lead to changes that have social implications as well (Robins et al 2019). While ‘a ton is a ton [of CO2]’, and while it might be a useful measure for carbon budgets it does not reveal much about the socio-economic consequences associated with reducing its emissions (in Carton et al 2021).

Indeed, if net zero is ‘science-based’, a just transition is ‘rights-based’ (Curran et al 2022). A just transition aims to address the adverse effects a low-carbon transition might have on society, thus preventing or at least mitigating any social harm. At the same time, it aims to seize opportunities arising from addressing social injustices.

The move to a net zero future entails profound changes for societies and economies. In the UK, for instance, one fifth of jobs will be affected by a low-carbon transition (Robins et al 2019). Climate adaptation and mitigation policies have long-term benefits for society (eg. preservation of biodiversity, improved public health, job creation, and enhanced energy security).

In the short-term, however, and if poorly managed, climate policies can result in unequal distributions of costs and benefits among different groups and countries (Ludden et al; Robins et al 2020). Transitioning from high-emitting activities may result in stranded workers and communities (Gambhir et al 2018, p. 3), as well as missed opportunities for employee retention and skill improvement (ILO, 2022a).

Net zero transitions may also negatively affect low-income consumers, peripheral regions, and local economies (Robins et al 2020). Social inequalities can also be perpetuated or solidified, especially among vulnerable groups, who may not be able to adjust to the changes associated with the transition.

As low-carbon energy sources expand, they may also create concerns related to human rights such as abuses of indigenous peoples’ rights, displacement, and loss of livelihoods (Gambhir et al 2018; Signorelli and Horvath, 2019). “Systematically factoring in such risks (…) is central to a just transition” (ILO, 2022a).

Taking action to address climate change does not automatically generate socio-economic benefits (Robins et al 2020). Therefore, climate action should be accompanied by policies that would mitigate socio-economic risks and maximise related opportunities. The need for climate mitigation and adaptation is well established, as is the need for addressing the social consequences of those actions.

Striking a right balance between the two, however, remains a challenge (Ludden et al 2021). It is important to note here that concerns related to justice are not to be used as an excuse for climate-related inaction (Robins et al 2020). A just transition is not at odds with climate mitigation and adaptions efforts, but rather an integral part of those efforts.

It recognises that countries, communities, businesses, and social groups have different capacities when facing a low- carbon transition. These differences must be addressed to ensure that ‘no one is left behind’.

The purpose of this paper is to contribute to the discussion of a just transition with a particular focus on the financial sector. The paper is structured as follows. In the first part, it discusses what a just transition means in general. The second part of the paper focuses on a just transition for financial institutions.

Starting with an overview of the various components of a just transition, and why a just transition is important to the financial sector, the paper then proceeds to present a brief overview of the existing frameworks for integrating a just transition into financial institutions’ strategies.

2. Just transition to net zero

2.1. Background

The idea behind a just transition appeared in the late 1970s when labour unions in the United States sought to support workers in polluting industries (Gambhir et al 2018; Morena et al 2018). Apparently, it was born when a trade unionist, Tony Mazzocchi, started advocating for the rights of workers exposed to toxic chemicals over the course of their careers (Pinker, 2020; Morena et al 2018).

The term was introduced in 1995 by Les Leopold and Brian Kohler who argued that the real choice is not between ‘jobs or the environment’, but rather ‘both or neither’ (in Morena et al 2018). The concept gained international prominence during the 2000s, particularly in the context of UN discussions on climate change and sustainable development (Morena et al 2018)1.

In 2015 the Paris Agreement called upon the Parties to consider “the imperatives of a just transition of the workforce and the creation of decent work and quality jobs” when taking actions to address climate change (UNFCCC, 2015).

In addition, the agreement notices the importance of climate justice, as well as the need for the Parties to “respect, promote and consider their respective obligations on human rights, the right to health, the rights of indigenous peoples, local communities, migrants, children, persons with disabilities and people in vulnerable situations and the right to development, as well as gender equality, empowerment of women and intergenerational equity,” when taking climate-related actions. It also recognises the specific needs and circumstances that developing countries might experience when transitioning to a green future.

The Paris agreement was followed by the International Labour Organization’s (ILO) Guidelines for a Just Transition (2015) and the Solidarity and Just Transition Silesia Declaration adopted at the UN COP24 in 2018 (UNFCCC, 2018). Since then, several countries (eg. Canada, Germany, South Africa, the EU, the UK) have also started developing initiatives related to a just transition (Robins et al 2021a).

In 2021, the G7 affirmed the ministers’ commitment to address environmental justice and just transition objectives (G7, 2021). Commitment to supporting a just transition has been further reinforced by the Glasgow Climate Pact (UNFCCC, 2021) and the Sharm el-Sheikh Implementation Plan (UNFCCC, 2022).

Although the concept of just transition has been around for some time, its incorporation into climate action by financial institutions is a relatively new, but fast-growing phenomenon. Recently, Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) released a joint statement outlining five High-Level Principles for a just transition (MDBs, 2021). The African Development Bank (2022) and European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD, 2020) have also initiated plans related to a just transition.

CDC Group together with other stakeholders have published a white paper on just transition in the banking sector (Clifford Chance LLP et al 2021) and developed just transition finance roadmaps for India (Tandon et al 2021) and South Africa (Lowitt, 2021).

Some banks have started supporting a just transition by integrating social justice into their environmental, social and governance (ESG) reports (eg. Citigroup, 2020), corporate social responsibility (CSR) policies (eg. Crédit Agricole, 2021), plans to support emerging markets (eg. Standard Chartered, 2022; Deutsche Bank, 2022), and assessment reports based on the principles for responsible banking (PRB) (Barclays, 2021).

In 2018, more than 160 investors committed to incorporating a just transition into their climate practices (UN PRI, 2020). In the UK, a coalition of more than 40 financial institutions, along with other stakeholders, formed the UK’s Financing a Just Transition Alliance (Robins, 2021b).

Financial institutions are grappling with the realisation that a net zero transition opens new opportunities and benefits, but at the same time might produce negative socio-economic implications as well.

Crucially, a central axiom of just transition thinking is that a green future may not be possible if not supported by measures aiming to tackle the social injustice that it might bring. Thus, the question is not whether ‘just’ will become a necessary part of any net zero transition path, but rather how it will be achieved.

2.2. What is a just transition?

Although everyone agrees that a just transition puts people at the centre of climate-related discussions, the debate over what constitutes a just transition is far from settled. A just transition has no commonly accepted definition (Spengler et al 2021; ILO, 2021; Wilgosh et al 2022).

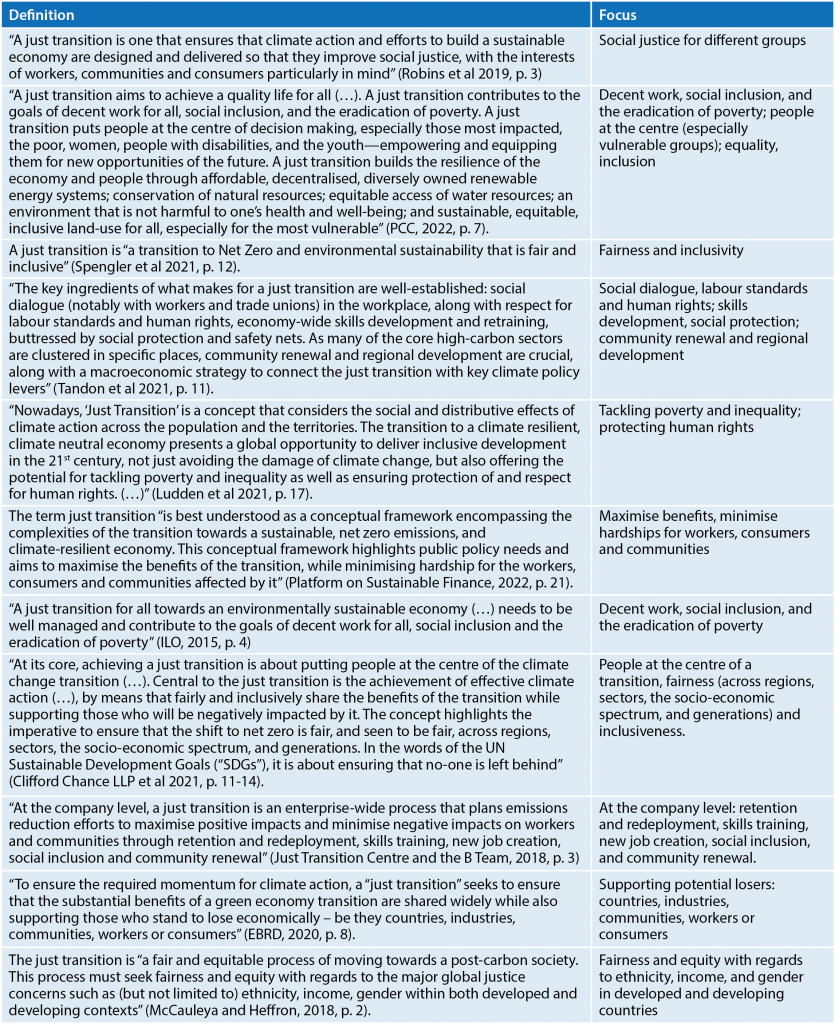

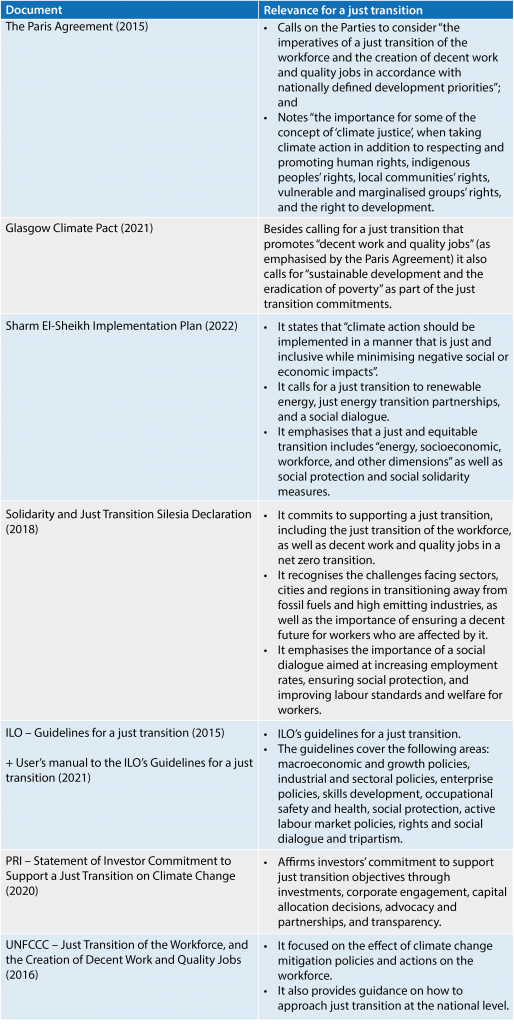

As a result, it can range from addressing concerns related to job losses during a low-carbon transition to more radical requests for transformation of the existing economic and political systems (Morena et al 2018). The table below illustrates how just transition definitions can vary.

Table 1. Examples of just transition definitions.

Definitions of a just transition, thus, might range from those that refer to broad objectives, ie. fairness and inclusivity (eg. Spengler et al 2021) to those that describe more concrete objectives, ie. decent work and the eradication of poverty (eg. PCC, 2022).

The concept of just transition has been often associated with addressing injustices after they occur, usually in the energy sector and in regard to job losses in the process of shifting away from fossil fuels (Just Transition Commission, 2021).

However, the socio-economic impacts related to a low-carbon transition usually extend beyond those felt by workers directly employed in the fossil fuel sector – they include a broader range of actors and issues such as impact on local communities, concerns related to land use for renewable energy, and consumers, households, and businesses who will be affected by rising energy prices (Pinker, 2020).

Beyond climate change, the term can also refer to environmental justice (see, eg. McCauleya and Heffron, 2018) and winners and losers of an energy transition (Cha, 2020). In addition to economic and social losses, a just transition can also involve cultural and emotional losses as a result of, for instance, close cultural ties with a local coal mining industry that needs to be closed (Cha, 2020).

Finally, as well as addressing injustices once they have occurred, the aim is also to prevent them from occurring in the first place. Just transition objectives differ depending on research domains, ideological viewpoints, or stakeholders’ needs. As a result, definitions of a just transition vary both in depth and breadth. These different approaches are discussed below in more detail.

When looking at stakeholders’ approaches to a just transition, there is a difference between those that are ‘group- or constituency-focused’ (ie. focused on a particular group of stakeholders) and those that are ‘sector-specific’ (ie. focused on a particular sector, instead of the economy as a whole) (Morena et al 2018).

Furthermore, there is a difference between just transition approaches based on the degree of change sought. Those are the following approaches:

(1) Status quo – which does not call for changing the rules of global capitalism, but rather for ‘a greening of capitalism’ based on voluntary, bottom-up and market-driven initiatives;

(2) Managerial reform – which seeks to modify certain rules and standards within the existing economic system such as those that relate to employment and occupational safety, but without challenging the existing system and balance of power;

(3) Structural reform – which aims to ensure both distributive and procedural justice, requiring institutional change and structural evolution; and

(4) Transformative approaches – which promote alternative routes to the existing economic and political systems that are seen as responsible for environmental and social problems (Morena et al 2018).

A further distinction can be made between these approaches in terms of the degree of inclusivity, which might range from exclusive (ie. geared toward a particular group) to inclusive (ie. geared towards the benefit of society as a whole) (Morena et al 2018). The above classifications of just transition are, thus, based on how much change (ranging from small and voluntary to more radical) and inclusivity each seeks.

Wilgosh et al (2022) provide a similar classification by making the distinction between two approaches: a limited approach to a just transition based on the existing market-based solutions and employment patterns, and an expansive approach that seeks structural transformation and more inclusivity.

Furthermore, bearing in mind that a net zero transition represents a process of exiting high-carbon activities and entering low-carbon activities at the same time, a just transition might be related to both – ‘transitioning into’ and ‘transitioning out of’ activities (SSE, 2020). Both ‘in’ and ‘out’ transitions will disrupt existing economic activities and generate new ones, with consequent socio- economic impacts (Clifford Chance et al 2021).

Also, different research traditions have their own version of ‘justice scholarship’ (Heffron, 2021):

(1) Climate justice – focuses on sharing the benefits and costs of climate change from a human rights standpoint (eg., the just transition should address the impacts of climate change on vulnerable groups);

(2) Energy justice – focuses on the application of human rights throughout the energy life cycle (eg. the just transition should address energy poverty); and

(3) Environmental justice – focuses on the social and environmental dimensions of a transition, and the involvement of all citizens in the development and implementation of environmental policies (eg. the just transition should address the communities affected disproportionately by pollution) (see Heffron, 2021; McCauleya and Heffron, 2018; Lo, 2021; Jenkins et al 2016).

Generally, climate and environmental justice focus on addressing injustices after they happen, whereas energy justice, at least in some cases, aims to address injustices before they happen (Heffron, 2021).

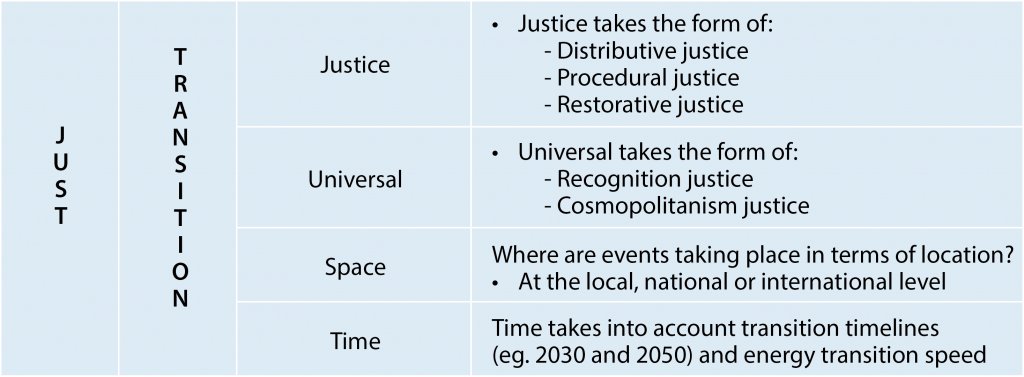

Recent definitions of a just transition, which link key dimensions of climate, energy, and environmental justice, distinguish between the following just transition approaches:

(1) Distributive justice – ensures fair distribution of costs and benefits;

(2) Procedural justice – ensures that everyone has equal access to decision-making processes;

(3) Recognition justice – ensures that all groups’ interests and needs are considered equally;

(4) Cosmopolitanism justice – refers to the transition effects from a global context; and

(5) Restorative justice – refers to repairing any injustice caused by a transition (see Heffron, 2021; McCauleya and Heffron, 2018; Ludden et al 2021; Williams and Doyon, 2019).

Space and time are also critical dimensions of a just transition (Heffron, 2021). Timelines (eg. 2030, 2050) influence transition speed (Heffron, 2021), while space may affect the degree of injustice. A transition needs to be grounded in ‘place-based realities’ (Robins et al 2020) and ‘considerations of local needs, capacity and priorities’ (Spengler et al 2021). Net job losses, for example, vary by region and country (Gambhir et al 2018).

Figure 1. The legal geography ‘Just’ framework for the just transition.

Source: Adapted from Heffron and McCauley (2018, p. 77).

This brief overview aims to raise awareness of the challenge of defining a just transition, and subsequently implementing related policies and plans. Depending on the context, the term might include anything from subtle, voluntary changes within the existing system of global capitalism to more radical societal changes.

Just transition might imply focusing on specific social groups (eg. workers and local communities), topics (eg. climate and energy transition), aspects of a net zero transition (eg. distribution and participation), and objectives (eg. eradication of poverty and inclusivity). Intuitively, all stakeholders understand what a just transition might imply. Terms such as fairness, inclusivity, and equality are well understood at the principle level.

However, the concept remains ambiguous when it comes to operationalising and taking action to address social injustices as part of net zero plans, as well as measuring and disclosing progress on a just transition. What is meant by ‘just’ might be subjected to various interpretations, based on a particular actor’s views and needs, and a context.

There is a need, therefore, for further clarification of what is meant by a just transition, especially in terms of the roles that various actors (including financial institutions) should play in addressing social injustices. To transition to a net zero (and nature-positive) future, all aspects of social and economic life would have to be transformed.

Every aspect of that road should be closely followed by measures that will assure that the transition is just. If there is no clear definition of a just transition and its components, social injustice may remain unaddressed.

The following sections aim to consider a just transition with a particular focus on the financial sector’s needs.

A central axiom of just transition thinking is that a green future may not be possible if not supported by measures aiming to tackle the social injustice that it might bring

3. Just transition and the financial sector: Existing definitions, practices, and guidelines

3.1. Defining a just transition for financial institutions

The current section provides a brief overview of what a just transition means based on existing guidelines for the financial sector.

Some of the most prominent just transition frameworks for financial institutions incorporate distributive, procedural, and restorative justice principles (eg. Curran et al 2022; Muller and Robins, 2022). They recommend addressing the distributional implications of a net zero transition, delivering positive social impacts for workers, communities and consumers, and engaging with workers and other stakeholders (Curran et al 2022).

To achieve a just transition, it is usually recommended that financial institutions need to engage in social dialogue, respect labour standards and human rights, facilitate skills development, support social protection, communities’ renewal, regional development, consumers and suppliers (Tandon et al 2021).

A just transition might also be defined through three mutually dependent elements: climate and environmental action, socio- economic distribution and equity, and community voice (Spengler et al 2021). The objective is sometimes more broadly defined – a just transition aims to maximise the economic and social benefits of climate action while minimising risks (ILO and Grantham Research Institute, 2022), it seeks to ensure that ‘no-one is left behind’ by providing fairness and inclusivity (PwC, 2022).

A just transition is also seen as a way of connecting climate-related concerns to other Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (Tandon et al 2021) or as the ‘social’ pillar of the ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) framework (Curran et al 2022).

It seems that the least common denominator is the understanding that both climate change and action will produce certain socio-economic injustices that should be prevented, mitigated, or compensated for in a fair manner.

There is also an understanding that any action related to a just transition should simultaneously be: (a) universal and place-based, (b) applied across all sectors as well as sector-specific, (c) all-inclusive and group-specific, and (d) dynamic as well as grounded in the status quo (Spengler et al 2021).

Financial institutions are expected to gain an understanding of the needs of different social groups, the risks they may face, and the opportunities for business that might arise as part of a net zero transition (Robins et al 2019). Their financial products and services should be designed to help clients achieve a net zero transition in a socially inclusive way (Robins et al 2020).

Usually, just transition frameworks for financial institutions identify workers, communities, suppliers, and consumers as key actors to be affected by a net zero transition (eg. Robins et al 2021a; Curran et al 2022). Their recommendations tend to be centred around these stakeholders. Some add to that group citizens (F4T, 2021b), indigenous peoples (ILO and Grantham Research Institute, 2022) and emerging markets (Standard Chartered, 2022).

‘Just nature transition’ frameworks for financial institutions have also begun to emerge (see Muller and Robins, 2022). The rationale is to address the socio-economic consequences of nature loss and actions to restore and preserve nature. Several just transition frameworks for the financial sector, like the one by Spengler et al (2021), include nature- and climate-related elements.

Since a number of financial institutions are seeking to assess climate- and nature-related financial risks and opportunities jointly, the development of just transition guidelines will likely follow a similar trajectory in the future.

3.2. Why is a just transition important for financial institutions?

Just transition objectives can only be achieved by shifting global finance and adopting investments that accelerate and support those objectives (Spengler et al 2021). The concept of a just transition is relatively new in the financial sector (Spengler et al 2021; Muller and Robins, 2021).

When used, it has been applied either very abstractly or narrowly to address the loss of jobs associated with a shift away from fossil fuels (Spengler et al 2021). Typically, investors look for either climate or social investments, rarely combining the two (Ibid.). A just transition should be about both. Its purpose is to integrate socio-economic concerns into climate-related finance and investments plans.

What makes a just transition significant for the financial sector? Firstly, financial institutions should incorporate a just transition into their plans to ensure compliance with growing national and international initiatives requiring a net zero transition to be just. All financial institutions are expected to align their strategies with the Paris Agreement and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

As mentioned earlier, the Paris Agreement calls all parties to align their policies with “the imperatives of a just transition” and climate justice, in addition to respecting and promoting human rights, indigenous peoples’ rights, local communities’ rights, vulnerable and marginalised groups’ rights and the right to development.

Besides calling for a just transition that promotes ‘decent work and quality jobs’, the Glasgow Climate Pact also calls for ‘sustainable development and the eradication of poverty’ as part of the just transition commitments (UNFCCC, 2021).

With the Sharm El-Sheikh Implementation Plan, just transition objectives have been further reinforced (UNFCCC, 2022). The document explicitly states that “climate action should be implemented in a manner that is just and inclusive while minimising negative social or economic impacts.”

It also calls for a just transition to renewable energy, just energy transition partnerships, and a social dialogue. The Plan emphasises that a ‘just and equitable transition’ includes ‘energy, socioeconomic, workforce, and other dimensions’ as well as social protection and social solidarity measures.

Similarly, since they connect environmental and social dimensions (eg. climate action and decent work) many SDGs overlap with just transition aims (Muller and Robins, 2022; Tandon et al 2021).

Aside from aligning their strategies with the Paris Agreement and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), financial institutions are also expected to adhere to human, social, and labour rights, as outlined in the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs) (UN, 2011), ILO standards, OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises (OECD Guidelines, 2011), and other relevant documents (Clifford Chance LLP et al 2021; Curran et al 2022).

Even though the UNGPs and OECD Guidelines do not provide a comprehensive framework for financial institutions to integrate just transition dimensions into their policies, they serve as a critical foundational element (Clifford Chance LLP et al 2021).

Secondly, financial institutions should aim to support a just transition due to ‘the risks of not doing so’, especially when it comes to potential litigation exposures (Clifford Chance LLP et al 2021).

Increasingly, countries are pledging to make their net zero transitions ‘just’ by including just transition objectives in their Nationally Determined Contributions (ILO, 2022a). Some countries, such as Belgium, Germany, and the Netherlands, have adopted or are considering laws related to mandatory human rights and environmental due diligence (Clifford Chance LLP et al 2021).

Likewise, the EU Taxonomy which defines sustainable activities requires compliance with minimum safeguards, meaning those carrying out economic activities must ensure alignment with the OECD Guidelines, UNGPs, the eight fundamental conventions identified in the ILO Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work, and the International Bill of Human Rights (Article 18, European Parliament and the Council, 2020).

All these initiatives increase the risk of overlooking socio-economic concerns related to a net zero transition, including the possibility of litigation. Though they may not produce legal effects immediately, financial institutions should begin adjusting to just transition requirements so that they can be ready to comply when they do (Clifford Chance LLP et al 2021).

Thirdly, the financial sector should support just transition efforts to reduce financial risks related to climate change and action. A just transition increases the support for green growth (Curran et al 2022). Some studies find that perceived fairness is an important predictor of public support for climate action (in Robins et al 2020).

Failure to consider socio-economic challenges could lead to climate action failing or being delayed, and consequently the financial sector may be adversely affected. Overlooking the risks of potential negative impacts on workers, businesses, or communities can result in operational and supply chains disruptions, changes in market demands, and deterioration of local economies, which in turn can negatively affect the health of the financial sector (ILO, 2022a).

A just transition thus helps financial institutions to manage systemic risks arising from climate change by integrating the environmental and social aspects of economic performance (PRI, 2020).

Besides, addressing social injustices related to the workforce and communities that may be negatively impacted by a net zero transition has become an ‘increasingly material driver for value creation’ (Ibid.), for instance by affecting customers’ ability to repay loans due to technological changes (Robins et al 2020).

Fourthly, a just transition is important for financial institutions because it creates space for new business opportunities. Addressing social concerns is critical to building a resilient green economy that develops the needed skills and capabilities (Curran et al 2022) in a timely manner.

Overlooking human capacities and skills to deal with a net zero transition can ‘bring less than optimal co-benefits’ (ILO, 2022a). Through collaboration with vulnerable sectors, groups, and regions, the financial sector can identify new net zero opportunities (Robins et al., 2020).

For instance, banks can adapt existing and develop new products, such as just transition linked corporate loans, in order to address socio-economic challenges and opportunities (Clifford Chance LLP et al 2021)2.

3.3. Just transition in the financial sector: what is new and what is old?

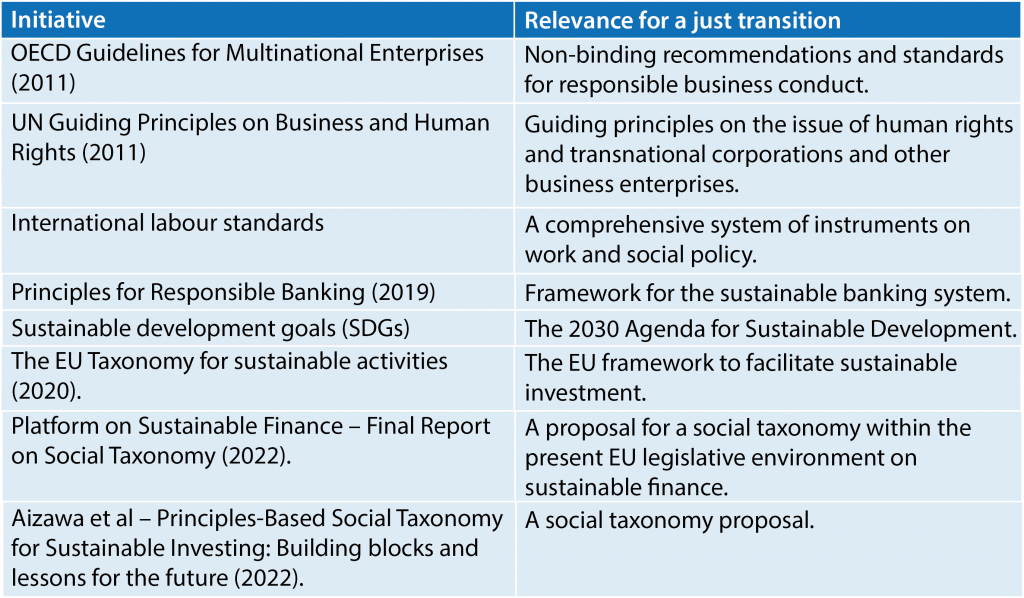

Although relatively new in the financial sector, the concept of just transition overlaps or is closely related to some of the existing practices and rules that financial institutions already align with.

As mentioned earlier, financial institutions are expected to adhere to human, social, and labour rights, as outlined in the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs), ILO standards, OECD Guidelines, and other relevant documents, such as the International Bill of Human Rights.

Although these documents do not explicitly refer to a just transition, they cover some of the just transition objectives, such as the protection of human rights, employment, the environment, public health, and consumer interests.

Just transition objectives are also closely related to SDGs especially those that concern decent work and economic growth (SDG 8), reduced inequalities (SDG 10), poverty elimination (SDG 1), climate action (SDG 13) and protection and restoration of biodiversity and ecosystems (SDGs 14 & 15).

A number of financial institutions have already put in place activities aimed at supporting the SDGs. To achieve the SDGs, it is essential to ensure ‘no one is left behind’ and to build an ‘inclusive and just society’ (UN, 2015). These are also the goals that a just transition seeks to achieve.

A just transition is also closely associated with Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) frameworks. According to some interpretations it is supposed to cover the social pillar of the ESG framework (see, eg. Curran et al 2022).

However, the environmental pillar of ESG often receives more attention than the social pillar (ILO, 2022a). For example, while Green Bonds represent the largest segment of the sustainable debt market, Sustainability-Linked Bonds (SLB) have only recently emerged (Ibid.).

Furthermore, financial institutions often consider environmental and social indicators separately, as part of their ESG disclosure frameworks, rather than addressing how social and climate issues intersect (UN PRI, 2022). To ensure a just transition they should connect the ‘E’ and ‘S’ pillars of their strategies (F4T, 2021b).

Financial institutions that focus on ESG considerations should consider whether and how they already incorporate aspects of just transition issues, and if so, where they may fall short (Clifford Chance LLP et al 2021).

Each of the above covers some aspects of a just transition, but not all. Besides, the goal of a just transition is to integrate socio-economic considerations into net zero transition plans and strategies.

It is not about considering environmental and socio-economic concerns separately, but rather simultaneously as part of transition plans and strategies aiming to avoid any social harm and maximise opportunities related to a net zero future.

Similarly, a just transition is about processes as well as outcomes (ILO, 2022a). It includes the participation, involvement, and support of all stakeholders through social dialogue.

Therefore, even though financial institutions may already apply certain principles and practices relevant to a just transition, they must do so in a more comprehensive and integrated manner so that potential socio-economic risks that could undermine a net zero transition are properly addressed while opportunities are seized.

3.4. Existing frameworks for incorporating a just transition into financial institutions’ strategies

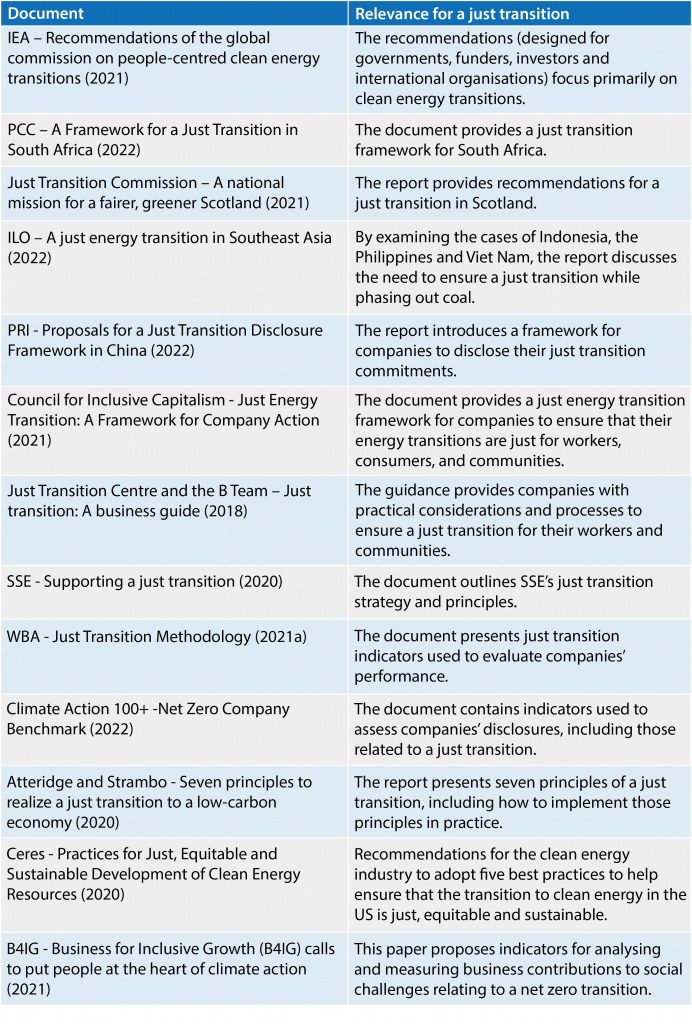

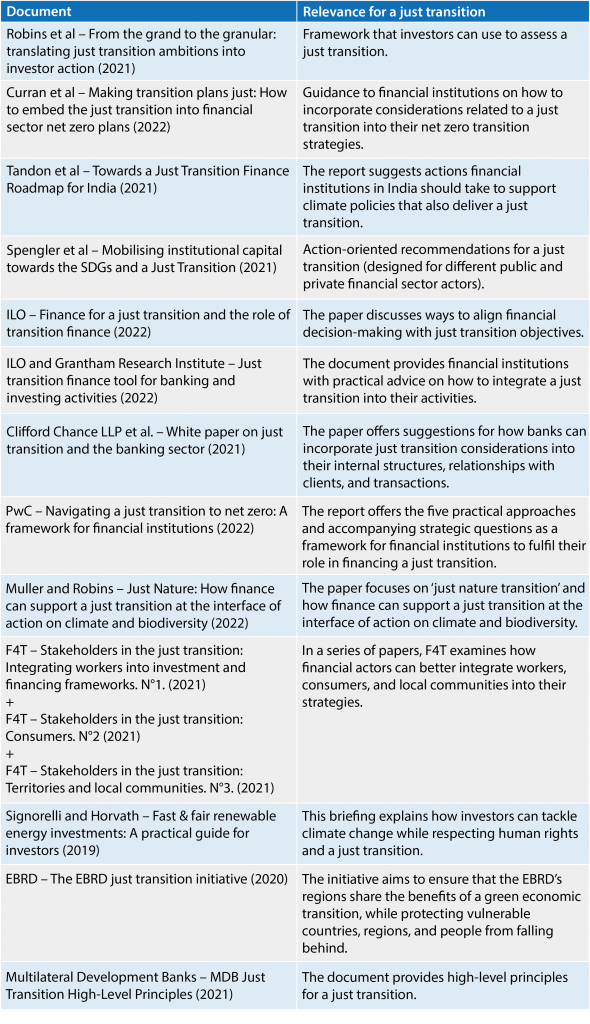

Generally, frameworks for implementing a just transition can be classified as those that focus specifically on a just transition (see Appendix 2, 3 and 4) and other related initiatives that do not explicitly refer to just transition objectives but intersect with them (see Appendix 1).

They can also be divided into those designed for governments and social actors (see Appendix 3) and those designed for financial institutions (see Appendix 4). This section focuses mainly on frameworks that are intended to provide recommendations for a just transition in the financial sector (listed in Appendix 4).

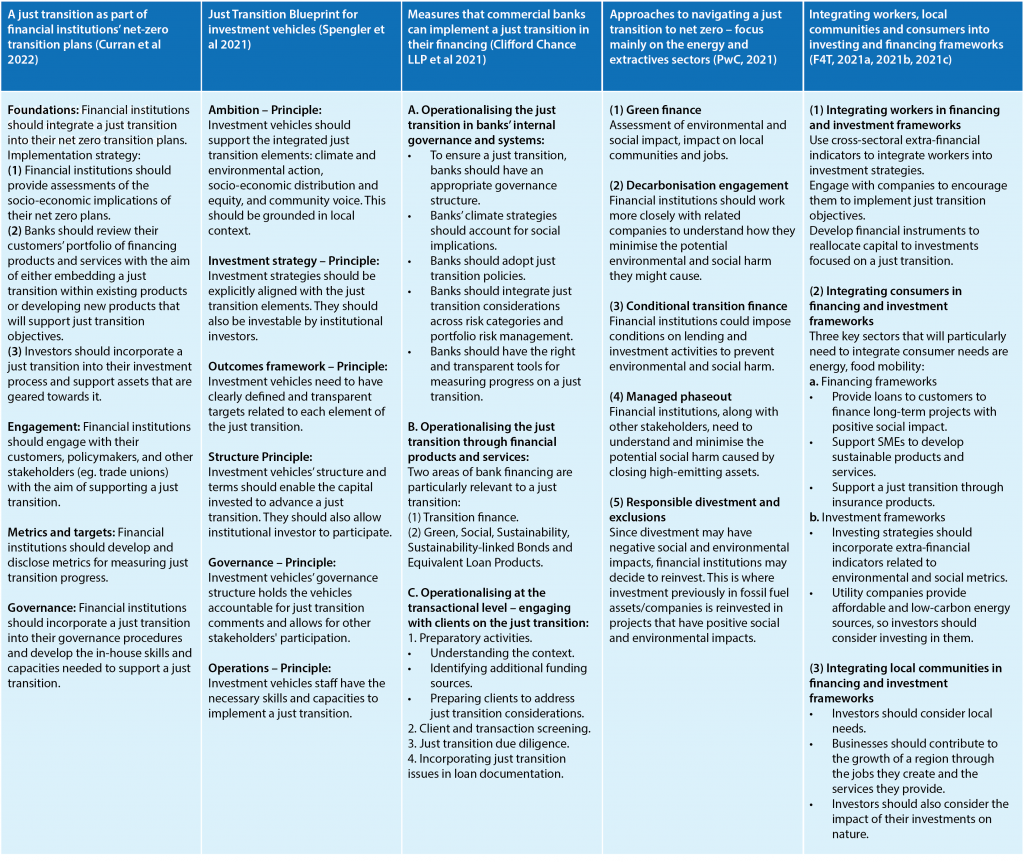

Some of the frameworks designed for the financial sector align their recommendations for a just transition with frameworks for financial institutions’ net zero transition plans (eg. Curran et al 2022). Others focus on investment vehicles (eg. Spengler et al 2021), commercial banks (eg. Clifford Chance LLP et al 2021), development banks (EBRD, 2020), financial institutions’ practical decision-making (eg. PwC, 2021), or the integration of human rights into renewable energy investments (Signorelli and Horvath, 2019).

While some offer more principle-based guidance, others provide more detailed guidance. Finally, some of the frameworks focus on particular countries (eg. Tandon et al 2021), while others provide more general recommendations.

Based on the review of those frameworks, Table 2 outlines key steps and principles the finance sector should consider to address just transition concerns.

In general, all reviewed frameworks recommend financial institutions to integrate just transition objectives into their policies, plans, governance structures and procedures, products and services, engagements with clients and other stakeholders, and disclosure frameworks.

Banks are expected to assist their clients and customers in aligning with just transition objectives. This includes providing loans to customers to finance projects with positive social impact, conducting just transition due diligence, encouraging product development aiming to address social injustices etc.

Supporting SMEs to develop sustainable products and services is seen as particularly significant in that respect. Transition finance, green, social, sustainability, and sustainability-linked bonds are also considered particularly significant areas of bank financing that should be improved to address social injustices.

Similarly, investors are also expected to support just transition objectives, by incorporating a just transition into their strategies, setting clear targets related to a just transition, and applying extra-financial indicators related to social impacts, among other things.

As divestment and decarbonisation engagement might have far reaching negative social impacts, it is recommended that financial institutions approach this issue with suitable care.

Table 2. An overview of selected frameworks addressing a just transition designed for the financial sector.

The analysed frameworks suggest that in addition to general principles, strategies to deal with the socio-economic effects of a net zero transition should also be sector- and location-specific. A one- size-fits-all approach is not recommended.

Some sectors, such as energy, food, and transport, are seen as particularly vulnerable to social injustices. However, the social implications extend beyond these sectors and should therefore be addressed appropriately.

A just transition does not apply only to ‘sectors undergoing decarbonisation’, but also to ‘net zero aligned and enabling activities that benefit from green financial flows’ (ILO, 2022a).

There is also agreement that while some financial actors and companies have started developing plans for a just transition, this has been far from common practice. Most companies do not consider a just transition (WBA, 2021b) and financial flows are not systematically aligned with just transition goals (ILO, 2022a).

One of the reasons for this relates to the difficulties in identifying and tackling “the components of the just transition agenda from a finance perspective because of a lack of consensus around definitions, limited standardisation of social metrics, difficulties in obtaining decision-useful data, emerging but still limited market recognition of the need to address socio-economic impacts of the decarbonisation process, immaturity of available processes and mechanisms focused on social parameters and the fact that social spending is often seen as a cost rather than an investment” (ILO, 2022a).

Existing frameworks provide clear guidance on how financial institutions can incorporate a just transition into their strategies, governance, and products. However, further work is required to identify and standardise all components of a just transition – that is, socio-economic risks resulting from a net zero transition, pathways to address those risks, metrics for evaluating progress on a just transition, and business opportunities associated with it.

Future work is also necessary to develop sector- specific guidelines and to consider both the short-term and long-term socio-economic consequences of a green future. Meanwhile, firms and financial institutions that do engage with the just transition agenda should do so in a comprehensive and integrated manner that aligns environmental and social objectives.

4. Conclusion

The purpose of this paper is to contribute to ongoing discussions regarding a just transition and the financial sector. It is intended to facilitate future considerations of a just transition by providing an overview of available definitions and frameworks related to its aims and components.

The paper suggests that a just transition represents a multidimensional concept, and it should be regarded as such by the financial sector. Focusing solely on employment in high-emitting sectors, as has been the case in the financial sector up until now, is not sufficient.

A just transition encompasses a much broader set of issues, such as the impact of a low-carbon transition on local communities, concerns related to land use for renewable energy, social inequalities, and eradication of poverty. These should be addressed in locally relevant and appropriate manner that respects the needs and concerns of specific stakeholders, especially the most vulnerable who are often voiceless in most settings.

Financial institutions should therefore start considering all these various components to ensure that a net zero transition is indeed just. Hence, to accelerate adoption and implementation by financial institutions, a broader consensus is needed on the definition of just transition.

An in-depth analysis and classification of socio-economic risks associated with net zero transitions that should be included in financial institutions’ standard risk assessments will be presented in a follow-up paper published by the Centre for Climate Finance & Investment (CCFI).

The analysed literature also suggests that environmental and socio-economic concerns should not be treated separately but rather simultaneously to avoid social harm and maximise opportunities associated with a green future. The financial sector is also expected to engage with other stakeholders (eg. workers, local communities, and indigenous peoples) and understand socio-economic challenges they might face.

Furthermore, financial institutions should assess the social impacts of their decisions and activities, assist clients in aligning with just transition objectives, encourage product development aiming to address social injustices, and develop in-house expertise and governance structures related to a just transition. To do so they should firstly commit to making their net zero strategies ‘just’ by defining clear targets and metrics for measuring success.

While some financial actors, such as multilateral development banks and private sector players, are taking a more active role in just transition initiatives, a significant gap remains in the alignment of financial flows with just transition goals (ILO, 2022a). Consequently, more work is needed to ensure that financial institutions are well-prepared for the challenges related to a just transition.

Besides identifying all relevant components of a just transition that should be considered by the financial sector, as discussed earlier, this also involves having a thorough understanding of the costs of a just transition as well as the business opportunities that are associated with it.

Appendix

Appendix 1. A not-exhaustive list of initiatives that intersect with the just transition objectives

Appendix 2. A not-exhaustive list of international agreements and initiatives that refer to a just transition

Appendix 3. A not-exhaustive list of frameworks addressing a just transition designed for governments and other societal actors

Appendix 4. A not-exhaustive list of frameworks addressing a just transition designed for the financial sector

Endnotes

1. For more about a brief history of just transition see Morena et al (2018).

2. For more examples of financial products that can support a just transition, see, for instance, Clifford Chance LLP et al. (2021, pp. 66–68).

References

African Development Bank (2022). The African Development Bank’s Just Transition Initiative to Address Climate Change in the African Context. Discussion Paper.

Aizawa, M et al (2022). Principles-Based Social Taxonomy for Sustainable Investing: Building blocks and lessons for the future. IISD Report.

Atteridge, A and Strambo, C (2020). Seven Principles to Realize a Just Transition to a Low-Carbon Economy. SEI policy report, June 2020.

Barclays (2021). Principles for Responsible Banking (PRB).

B4IG (2021). Business for Inclusive Growth (B4IG) Calls to Put People at the Heart of Climate Action. November 8, 2021.

Carton, W et al (2021). Undoing Equivalence: Rethinking Carbon Accounting for Just Carbon Removal. Perspective article. Frontiers in Climate, 3:664130. Sec. Negative Emission Technologies.

Ceres (2020) Practices for Just, Equitable and Sustainable Development of Clean Energy Resources.

Cha, MJ (2020). A Just Transition for Whom? Politics, Contestation, and Social Identity in the Disruption of Coal in the Powder River Basin. Energy Research & Social Science, 69, 101657.

Citigroup (2020). Environmental, Social and Governance Report.

Clifford Chance LLP et al (2021). Just Transactions: A White Paper on Just Transition and the Banking Sector.

Climate Action 100+ (2022). Climate Action 100+ Net Zero Company Benchmark v1.2. October 2022.

Council for Inclusive Capitalism (2021). Just Energy Transition: A Framework for Company Action.

Crédit Agricole (2021). Our Sector Policies.

Curran, B et al (2022) Making Transition Plans Just: How to Embed the Just Transition into Financial Sector Net Zero Transition Plans. London: Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, London School of Economics and Political Science.

Deutsche Bank (2022). Deutsche Bank Supports Indonesia Just Energy Transition Partnership.

EBRD (2020) The EBRD Just Transition Initiative. Sharing the Benefits of a Green Economy Transition and Protecting Vulnerable Countries, Regions and People from Falling Behind.

European Parliament and of the Council. (2020). Regulation (EU) 2020/852 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 June 2020 on the Establishment of a Framework to Facilitate Sustainable Investment and Amending Regulation (EU) 2019/2088 (Text with EEA relevance).

F4T (2021a) Stakeholders in the just transition: Integrating Workers into Investment and Financing Frameworks. N°1.

F4T (2021b) Stakeholders in the Just Transition: Consumers. N°2.

F4T (2021c) Stakeholders in the Just Transition: Territories and Local Communities. N°3.

Gambhir, A et al (2018). Towards a Just and Equitable Low-Carbon Energy Transition. Grantham Institute Briefing Paper No 26, August 2018.

G7 Ministers (2021). G7 Climate and Environment: Ministers’ Communiqué. London, 21 May 2021.

Heffron, RJ (2021). Achieving a Just Transition to a Low-Carbon Economy. Palgrave Macmillan Cham.

Heffron, R and McCauley, D (2018). What is the ‘Just Transitions’? Geoforum, 88, 74-77.

IEA (2021) Recommendations of the Global Commission on People-Centred Clean Energy Transitions.

ILO (2022a) Finance for a Just Transition and the Role of Transition Finance. Input paper prepared for the G20 Sustainable Finance Working Group under the Indonesian Presidency.

ILO (2022b) A Just Energy Transition in Southeast Asia: The Impacts of Coal Phase-out on Jobs.

ILO (2015). Guidelines for a Just Transition Towards Environmentally Sustainable Economies and Societies for All.

ILO and Grantham Research Institute for Climate Change and the Environment (2022). Just Transition Finance Tool for Banking and Investing Activities.

Jenkins, K et al (2016). Energy Justice: A Conceptual Review. Energy Research & Social Science, 11, 174-182.

Just Transition Centre and the B Team (2018). Just Transition: A Business Guide.

Just Transition Commission (2021). A National Mission for a Fairer, Greener Scotland.

Lo, K (2021). Authoritarian Environmentalism, Just Transition, and the Tension Between Environmental Protection and Social Justice in China’s Forestry Reform. Forest Policy and Economics, 131, 102574.

Lowitt, S (2021). A Just Transition Finance Roadmap for South Africa: A First Iteration. Trade & Industrial Policy Strategies (TIPS).

Ludden, V et al (2021). Social Impacts of Climate Mitigation Policies and Outcomes in Terms of Inequality. Final Report. Rambøll Management Consulting A/S. DK reg.no. 60997918.

McCauleya, D and Heffron, R (2018). Just Transition: Integrating Climate, Energy and Environmental Justice. Energy Policy, 119, 1-7.

Morena, E et al (2018). Mapping Just Transition(s) to a Low-Carbon World. A Report of the Just Transition Research Collaborative.

Muller, S and Robins, N (2022). Just Nature: How Finance Can Support a Just Transition at the Interface of Action on Climate and Biodiversity. London: Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment and Centre for Climate Change Economics and Policy, London School of Economics and Political Science.

Muller, S and Robins, N (2021). Policy brief: Financing the Just Transition Beyond Coal. October 2021. London: Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment. PPCA.

Multilateral Development Banks. (2021). MDB Just Transition High-Level Principles.

OECD (2011). OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises. OECD Publishing.

PCC (2022). A Framework for a Just Transition in South Africa.

Pinker, A (2020). Just Transitions: A Comparative Perspective. A Report prepared for the Just Transition Commission. The James Hutton Institute & SEFARI Gateway.

Platform on Sustainable Finance (2022). Final Report on Social Taxonomy.

PwC (2022). Navigating a Just Transition to Net Zero: A Framework for Financial Institutions.

Robins N, et al (2021a). From the Grand to the Granular: Translating Just Transition Ambitions into Investor Action. London: Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment and Centre for Climate Change Economics and Policy, London School of Economics and Political Science.

Robins N et al (2021b). Just Zero: 2021 Report of the UK Financing a Just Transition Alliance. London: Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, London School of Economics and Political Science.

Robins, N et al (2020) Financing Climate Action with Positive Social Impact: How Banking Can Support a Just Transition in the UK. London: Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, London School of Economics and Political Science.

Robins, N et al (2019). Banking the Just Transition in the UK. Policy insight, October 2019. Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment and the Sustainability Research Institute.

Signorelli, A and Horvath, E (2019). Fast & Fair Renewable Energy Investments: A practical guide for investors. Business & Human Rights Resource Centre.

Spengler, L et al (2021). Mobilising Institutional Capital Towards the SDGs and a Just Transition. Full Report. Workstream B. Impact Taskforce.

SSE (2020) Supporting a Just Transition.

Standard Chartered (2022). Just in Time: Financing a Just Transition to Net Zero.

Tandon, S et al (2021). Towards a Just Transition Finance Roadmap for India: Laying the Foundations for Practical Action. Practical thinking on investing for development. Insight.

UN (2015). Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

UN (2011). Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. Implementing the United Nations “Protect, Respect and Remedy” Framework.

UN PRI (2022). Investing for a Just Transition: Proposals for a Just Transition Disclosure Framework in China.

UN PRI (2020). Statement of Investor Commitment to Support a Just Transition on Climate Change.

UNEP FI (2021). Principles for Responsible Banking. Guidance Document.

UNFCCC (2021). Glasgow Climate Pact.

UNFCCC (2022). The Sharm el-Sheikh Implementation Plan. (2021).

UNFCCC (2018). Solidarity and Just Transition Silesia Declaration. COP24 to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), 3 December 2018, Katowice, Poland.

UNFCCC (2016). Just Transition of the Workforce, and the Creation of Decent Work and Quality Jobs. Technical paper.

UNFCCC (2015). The Paris Agreement.

WBA (2021a). World Benchmarking Alliance: Just Transition Methodology.

WBA (2021b). Just Transition Assessment 2021. Are High-Emitting Companies Putting People at the Heart of Decarbonisation?

Wilgosh, B et al (2022). When Two Movements Collide: Learning from Labour and Environmental Struggles for Future Just Transitions. Futures, 137 (2022) 102903.

Williams, S and Doyon, A (2019). Justice in Energy Transitions. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 31 (2019): 144–153.

This article is based on a September 2023 briefing paper published by the Centre for Climate Finance & Investment at Imperial College Business School. This briefing paper was authored by Ivana Popovic, Alexandre C Köberle, and Michael Wilkins. The authors thank Ajay Gambhir (Imperial College London) for his review and comments.

The Centre for Climate Finance & Investment at Imperial College Business School

The Centre for Climate Finance & Investment (CCFI)’s purpose is to unlock solutions within mainstream capital markets to address the challenges posed by global climate change. We investigate how financial markets and organizations are affected by climate change; defining and quantifying the risk associated with climate change and undertaking research on how capital markets are responding. Our work is generating a new understanding of the multi-trillion-dollar investment opportunity encompassing renewable energy, clean technologies, and climate-resilient infrastructure.

Combining interdisciplinary research with real-world experience, the CCFI is creating a point of interface between academics and practitioners. Researchers working with the CCFI bridge the academic and business worlds through research and industry collaborations. Founded in 2017, through the generous support of Quinbrook Infrastructure Partners, the Centre aims to produce high impact academic research as well as timely working papers and reports that influence the market.