Time to step up policy coordination in the euro area

Reinhard Felke is Director for Policy, Strategy and Communication, DG ECFIN, and Nicolas Philiponnet is Deputy Head of Unit, DG ECFIN, at the European Commission

The euro area economy has weathered the shock emanating from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine with impressive resilience. In spite of initial worst-case scenarios, it now looks like the euro area could avoid a recession altogether and recent readings suggest that inflation rates may have peaked already.

Irrespective of these positive macroeconomic developments, risks abound on the horizon, requiring policymakers’ sustained vigilance and action. This column focuses on diverging inflation trends in the euro area, the interplay between monetary and fiscal policy, and supply-side issues.

In an effort to contain the shock originating from Russia’s aggression in Ukraine, European governments have adopted a host of emergency measures to support households and companies. While this has mitigated energy poverty, inflation, and the drop in living standards, measures have often not been entirely coordinated and designed in optimal fashion (Arregui et al 2022).

Moreover, specific measures differed widely, not only in terms of design features but also in terms of size, depending on individual governments’ fiscal space (European Commission 2022b).

High inflation and recession fears rightly called for demand-side policy responses to support vulnerable households and corporates (Bethuyne et al 2022), but beyond the very short term, these can only be successful when partnered with a much broader and longer-term policy agenda to limit energy demand, develop alternative sources of energy, and improve productivity.

Figure 1. Components of HICP inflation in the euro area, 2007-2022

Note: Annual inflation; monthly data.

Diverging inflation trend in the euro area

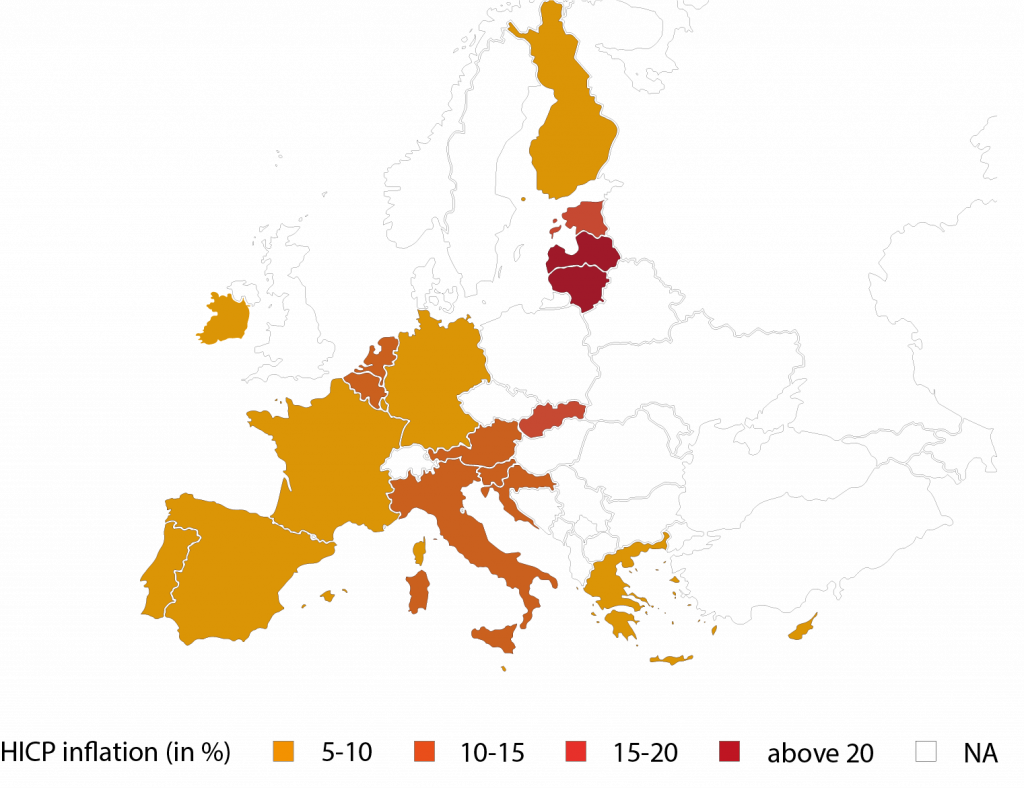

Inflation is high in all euro area member states, but it also shows striking heterogeneity across countries. Discrepancies in inflation rates across the euro area have gone less noticed in the policy debate so far.

Although they are exposed to the same global factors impacting energy prices, the annual inflation rate was above 20% in Latvia and Lithuania in December and below 7% in Spain, France and Luxembourg (Figures 2).

Such large divergences are unprecedented since the creation of the euro area. They are to a large extent driven by economic structure and country-specific energy intensity, that is, the energy necessary to produce one unit of value added in the economy. Structural features drive in particular the extent to which increases in energy prices pass through to other sectors and goods in the economy.

Policy measures taken by individual countries to compensate workers and companies, in some cases by muting the energy price increases also contribute to price divergences.

Inflation pressures are expected to ease gradually going forward, but this will not necessarily take place at an even pace throughout the currency union. Persistent gaps in price and wage inflation across the euro area could impede the good functioning of the euro area and they call for particular attention.

Addressing high inflation and the consequences of the energy shock remains a key challenge for policymakers in the euro area. A coordinated policy response is needed to avert long-term divergences and fragmentation

First, divergences make it more challenging to ensure that the single monetary policy is effective throughout the euro area. Second, price differential may translate into competitiveness divergences driving persistent differences in economic and labour market performance.

It is worth recalling that it was ten years of build-up in external imbalances within the euro area’s early days that laid the foundation for the euro crisis in 2010.

Vigilance and policy coordination in this respect is therefore warranted, reinforcing the relevance of tools such as the Macroeconomic Imbalance Procedure within the European Semester.

Figure 2. HICP inflation in the euro area, December 2022 (%)

Managing the policy mix

Confronted with a clear deceleration in economic activity and still high inflation, fiscal policymakers are in a tight spot. Fiscal policy needs to respond to social needs and support vulnerable, yet viable, energy-intensive companies, but it should also not provide an inflationary push to the economy.

In a context where monetary conditions are tightening, there is a risk that fiscal and monetary policy end up pulling in opposite directions. This is a very different situation from the COVID-19 period, where the accommodative monetary policy and the supportive fiscal stance acted in sync. The budgetary plans of euro area countries currently foresee an overall neutral fiscal stance for 2023, which is appropriate.

However, this stance could become much more expansionary if the emergency energy measures, which are currently expected to be rolled back in 2023, end up being extended. Much will thus depend on developments in energy prices and on the policy reactions to these.

If supports continue to be required, further efforts will be needed to increase the quality and targeting of the related measures. So far, only 20% of energy measures are income measures targeted to vulnerable households or energy-intensive companies (European Commission 2022a).

Most measures are poorly targeted and, more often than not, they distort prices and reduce the incentives to lower energy consumption. There is a consensus on the need to enact temporary, targeted, and non-distortionary measures moving away from broad-based price measures (Eurogroup 2022).

Still, the political pressure to lower actual energy prices, together with the difficulties of designing and rolling out well-targeted income measures, will remain an obstacle. A common approach at the EU level to adopt two-tier energy price systems, according to which a lower price is applied for a basic share of the energy consumption, could be instrumental.

Fiscal policy’s focus on addressing the immediate impact of the energy crisis should not crowd out the long-term response to structural challenges. The green and digital transition, but also security concerns, call for additional investment.

Most of the investment needed for the green transition is expected to come from the private sector but public spending still has a role to play, for instance as part of large infrastructure projects or to support a green industrial policy (Terzi et al 2022).

At a time when public debt in some euro area member states is at a record-high level, the fiscal space available at the national level to support investment needs for the long-term is limited. The increase in interest rates, which will gradually feed in higher debt service, is set to weigh on member states’ debt dynamics.

In this context, EU level instruments can provide support (European Commission 2023). The need to respond to long-term reform and investment needs while addressing short-term policy challenges is the key rationale for the Recovery and Resilience Facility, launched in early-2021, and of the REPowerEU initiative, on which the Council and the European Parliament reached an agreement in December 2022.

Preventing entrenched competitiveness differentials

As energy prices increases diffuse throughout the economy, the competitiveness of euro area companies vis-à-vis international competitors is affected.

More energy-intensive production processes, and in particular upstream processes, are affected the most. However, inter-sectoral dependency means that even sectors with relatively limited energy content see a rise in input prices.

Within sectors, more vulnerable companies, and in particular SMEs, may find it difficult to improve energy efficiency in the short term. It is therefore important to facilitate adjustment and to do so in a coordinated manner across the EU.

Higher competition can contribute to lower inflation and provides further incentives for companies to increase energy efficiency. A more efficient insolvency framework can also support the reallocation of resources associated to the energy transition.

In the short term, however, temporary support schemes to help vulnerable firms weather the sudden increase in energy prices, in line with the state aid framework, are useful (European Commission 2023).

However, differences in the level of public support, together with heterogeneous energy price inflation across countries, impacts on relative competitiveness within the euro area.

Within the Single Market, support should be coordinated to avoid harmful distortion to fair competition and a possible ‘subsidy race’ that would weigh on public finances and delay the energy transition.

Eventually, as the costs for carbon-intensive energy will remain elevated, efforts to increase energy efficiency and the use of renewable energy are key to maintain euro area companies’ competitiveness.

Developments in wages in the face of high inflation also remain a key point of attention for policymakers and social partners. Compensation per employee increased in 2022, but at a pace that was much below inflation (Figure 3).

On the upside, the contained wage developments have contributed to keeping inflation expectations well-anchored. This implies however that the purchasing power of wage has eroded – and is expected to continue doing so in 2023 (European Commission, 2022a) – holding back consumption in the short term.

The impact of inflation is strongly regressive, hitting lower income levels disproportionally hard. This calls for an adequate update in the minimum wage, and targeted social benefits and tax measures that can alleviate the impact on low-wage workers. Mirroring the heterogeneity in inflation, developments in nominal wages are very different from country to country.

Going forward, wages are expected to accelerate in a staggered manner in order to gradually recapture lost purchasing power. There is a thus risk that, even if energy prices recede, divergences in unit labour costs persist over time.

It will be important that future wage growth remains in step with relative productivity developments to avoid that divergences in unit labour costs become entrenched and contribute to widening competitiveness gaps across the euro area.

Figure 3. Nominal and real compensation per employee

Conclusion

Addressing high inflation and the consequences of the energy shock remains a key challenge for policymakers in the euro area. Given the heterogenous impact across the area, a coordinated policy response is needed to avert long-term divergences and fragmentation.

With its proposal for the euro area recommendation, which was approved by the Council on 17 January, the Commission has outlined a comprehensive policy agenda encompassing fiscal, labour market, social and structural policies (European Commission 2022c).

It echoes the Eurogroup’s call for coordinated energy measures. There is an overall consensus on the way forward, and the next few months will put the resolve of member states and their ability to adopt a coordinated approach to the test. The recent agreement on REPowerEU and the effective implementation of the RRF are encouraging signals in that respect.

References

Arregui N, O Celasun, D Iakova, A Mineshima, V Mylonas, F Toscani, Y Wong, L Zeng, L and J Zhou (2022), “Targeted, Implementable, and Practical Energy Relief Measures for Households in Europe”, IMF Working Paper No. 2022/262.

Bethuyne, G, A Cima, B Döhring, Å Johannesson Lindén, R Kasdorp and J Varga (2022), “Targeted income support is the most social and climate-friendly measure for mitigating the impact of high energy prices”, VoxEU.org, 6 June.

Eurogroup (2022), “Eurogroup statement on draft budgetary plans for 2023”, Eurogroup statements and remarks, December.

European Commission (2022a), European Economic Autumn 2022 Forecast, European Economy Institutional Paper 187, DG ECFIN, November.

European Commission (2022b), Euro area report, European Economy Institutional Paper 193, DG ECFIN, December.

European Commission (2022c), Recommendation for a Council Recommendation on the economic policy of the euro area, COM(2022) 782 final.

European Commission (2023), A Green Deal Industrial Plan for the Net-Zero Age, COM(2023) 62 final.

Terzi, A, M Sherwood and A Singh (2022), “Industrial Policy for the 21st Century: Lessons from the Past”, European Economy 157.

This article was originally published on VoxEU.org.