Resilient global supply chains and implications for public policy

Cyrille Schwellnus, Antton Haramboure, and Lea Samek are all Economists at the Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development

Widespread supply disruptions during the COVID-19 pandemic raised concerns about the risks from globalised value chains. This column studies the resilience of global supply chains using new measures of supply chain dependencies and concentration across the world.

It finds that the impact of mobility restrictions on output are greater in industries with few supplying countries (high geographic concentration) and few supplying firms within the industry (high industry concentration). Public policies can enhance resilience by promoting management and worker skills (ex ante), using targeted fiscal support (ex post), and increasing geographic diversification of supply chains.

The globalisation of supply chains – loosely defined as an increasing share of imported intermediate goods and services in output – has raised productivity and boosted the participation of lower-income countries in international trade (Irwin 2022, OECD 2013). But widespread supply disruptions in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic have raised concerns that globalised supply chains expose domestic production to shocks from abroad, including by creating strategic dependencies on a small number of key players (Javorcik 2020, OECD 2021).

For instance, widespread shortages of critical medical equipment (eg. respirators) and critical inputs into manufacturing (eg. semiconductors) during the COVID-19 pandemic have triggered a debate about the desirability of onshoring and the geographical diversification of inputs.

Mapping global supply chain dependencies

In a recent project, we analyse the resilience of global supply chains in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic with a view to providing insights for public policies. In our first paper (Schwellnus et al 2023b), we draw a detailed map of global supply chain dependencies based on new indicators that account for both the size and the complexity of supply chain exposures1.

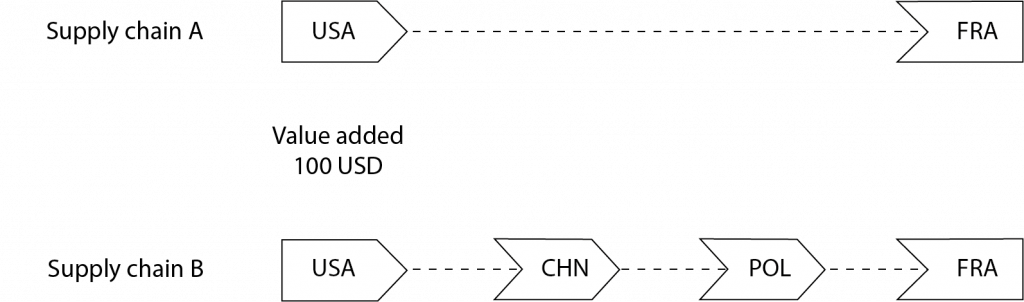

Following a simple but powerful insight of Baldwin and Freeman (2022), our indicators are based on gross trade and gross output rather than value added, thereby implicitly accounting for the fact that longer supply chains may be more vulnerable to disruptions.

To see this, consider the stylised supply chains in Figure 1. Suppose the US produces a semiconductor that embodies $100 of US value added. The short (and simple) supply chain A consists of direct exports to France. In the longer (and more complex) supply chain B, the US exports the semiconductor to China, which embodies it in a display and exports it to Poland, which, in turn, embodies it in a car and exports it to France. It is plausible that supply chain B is more vulnerable to disruptions than supply chain B even though the exported value added from the US to France is the same.

Figure 1. Longer supply chains are more vulnerable to disruptions

Our global map of supply chain dependencies based on these indicators emphasises the potential risks related to supply chain concentration. First, some industries are not only highly dependent on foreign inputs but also on geographically highly concentrated suppliers, making them particularly vulnerable to disruptions. This is, for instance, the case of the automotive and information and communications technology (ICT) and electronics industries that were heavily affected by supply disruptions in the wake of COVID-19.

Second, China is a critical choke point in global supply chains, with global supply and demand across a broad range of industries – especially manufacturing and mining – being heavily concentrated in China. Highly concentrated supply chains may be particularly risky by making rapid substitution to alternative suppliers in case of a shock very costly.

The key challenge for public policies will be to preserve the benefits of global sourcing for the overwhelming majority of supply chains while limiting costs when resorting to risk mitigation strategies in strategically important and highly concentrated ones

The transmission of foreign shocks through global supply chains

The econometric analysis in our second paper shows that our indicators of global supply chain dependencies are not only plausible but empirically relevant (Schwellnus et al 2023a). In this paper, we use exogenous mobility shocks during the COVID-19 pandemic to estimate the transmission of foreign disruptions on domestic output through global supply chains.

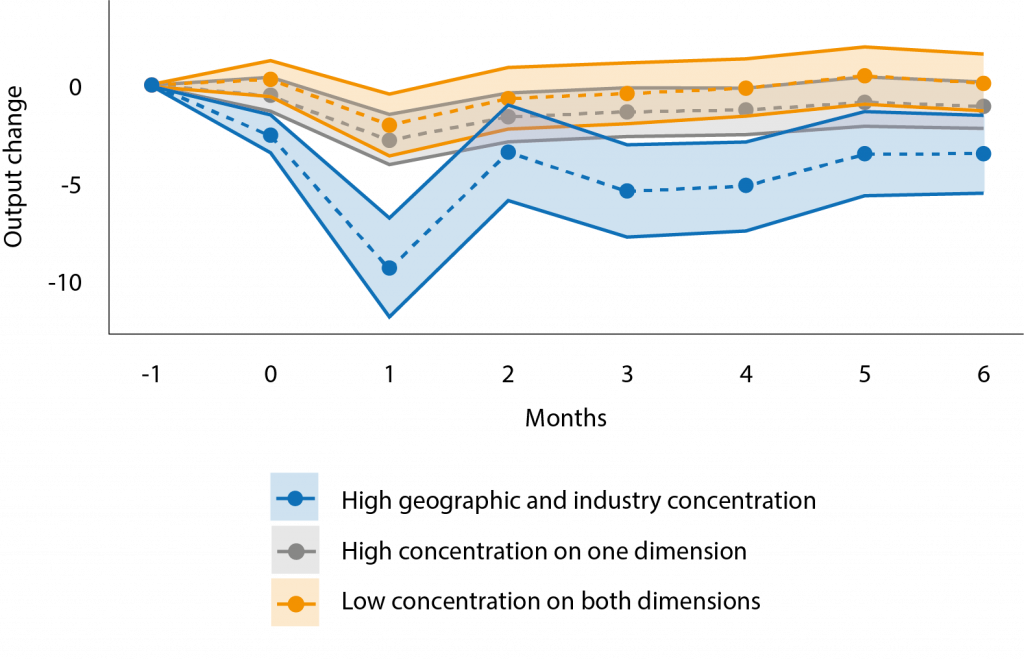

We find that our indicators of global supply chain dependencies are economically and statistically significant in transmitting foreign disruptions (Figure 2). The effects are particularly large in industries with few supplying countries (high geographic concentration) and few supplying firms within the industry (high industry concentration), in which the average quarterly output decline in response to a one standard deviation tightening of mobility restrictions abroad is about 5%2. To put this into perspective, the tightening of mobility restrictions in the spring of 2020 amounted to two standard deviations.

Figure 2. Supply chain concentration amplifies the output decline in response to a shock

One way that public policies can enhance global value chain resilience is by facilitating a quick rebound of output, either before a shock occurs (agility policies) or after it materialises (adaptation policies). Our econometric results suggest that promoting management and worker skills is a crucial agility policy by allowing for a rapid restructuring of production. Well-targeted government fiscal support in the form of grants, loan guarantees, and support for workers stands out as a significant adaptation policy.

Another way that public policies can enhance global value chain resilience is by mitigating the risk that shocks from abroad are transmitted to the domestic economy in the first place. We find that geographical diversification would reduce the adverse effects on output of a simulated shock to Chinese production in the most exposed downstream industries by up to 25%.

The partial onshoring of production (in addition to diversification) would only have very limited additional benefits in terms of shielding domestic production from shocks. Moreover, onshoring may come at a significant cost in terms of large up-front investments and/or higher production costs.

The shielding effects of technological innovation that reduces dependencies on specific inputs sourced from abroad (eg. fossil fuels) are comparable to diversification but require large technological shifts that may take time to materialise.

Implications for public policies

So what do our results imply for the overall public policy design to strengthen the resilience of global supply chains? Our results suggest that a key factor shaping the appropriate policy response to global supply chain risk is geographical concentration of supply.

Another crucial determinant is the strategic importance of the relevant value chain. From an economic perspective, a strategically important value chain provides an essential input to a wide range of domestic downstream industries (eg. critical raw materials) or provides significant technological spillovers to the wider economy (eg. semiconductors)3.

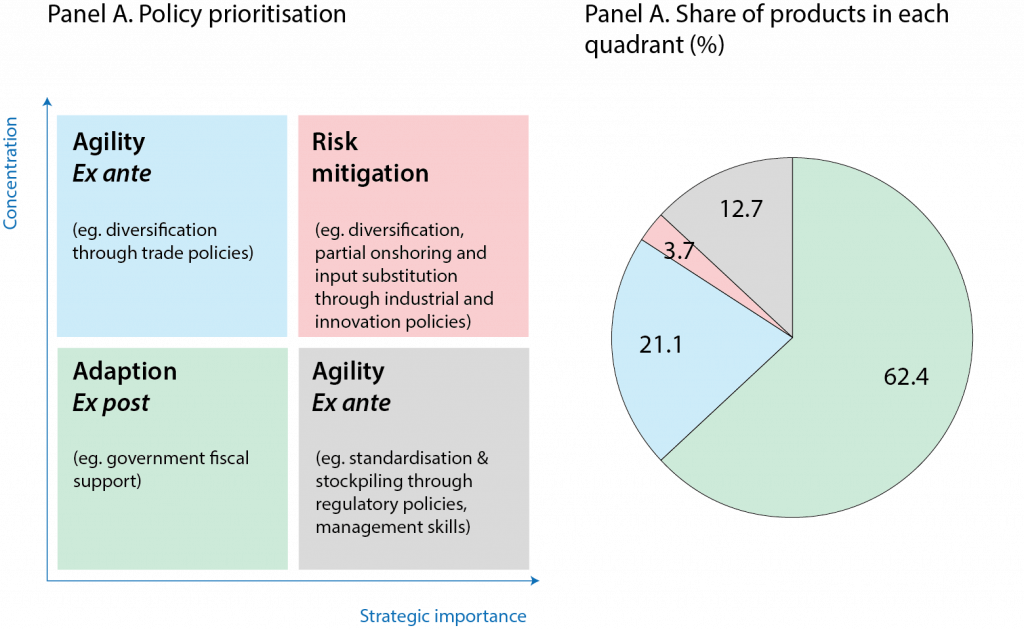

Concerns about global supply chain risk are most pronounced in supply chains that are both highly concentrated and strategically important (Figure 3, Panel A, top-right quadrant). For instance, given that semiconductor production is highly concentrated in a small number of key players and semiconductors are a critical input into a broad range of other industries (including national defence), a disruption of the supply chain would have large adverse macroeconomic consequences (Haramboure et al forthcoming).

In such supply chains, the benefits of risk mitigation strategies to limit foreign exposures, such as diversification of input suppliers (including through near and partial onshoring of production) and technological innovation to substitute specific inputs may, in some cases, justify high upfront investment costs and increases in operating costs.

Figure 3. Policies need to be tailored to the specific supply chain

In strategic value chains where suppliers are geographically diversified (eg. a range of medical, pharmaceutical, and ICT products), policies could promote agility, including through the standardisation of inputs and the holding of adequate inventories.

In non-strategic value chains with few suppliers (eg. parts of the textiles and apparel value chain), public policies could promote greater diversification through trade policies that provide better market access to small suppliers. In non-strategic value chains with many suppliers (eg. construction materials), the focus should be on ex-post adaptation measures through fiscal support in case of exceptionally large disruptions.

The overwhelming majority of supply chains are non-strategic and non-concentrated, with only a small fraction being strategically important and highly concentrated (Figure 3, Panel B). Based on a common threshold of geographic supplier concentration (Herfindahl-Hirschman Index above 2500) and a list of strategic products maintained at the OECD, about 62% of supply chains are neither dependent on concentrated suppliers nor strategically important.

Only about 4% are both strategically important and highly concentrated. Even though these proportions are only illustrative due to the ad-hoc definitions of geographic concentration and strategic importance, they nonetheless imply that risk mitigation policies are relevant only for a small fraction of supply chains.

In sum, in the overwhelming majority of global supply chains, ex-ante agility and ex-post adaptation policies are likely to be sufficient to deal with disruptions. Moreover, even in highly concentrated and strategically important supply chains, the potential benefits of risk mitigation policies need to be balanced with potential costs.

The key challenge for public policies will be to preserve the benefits of global sourcing for the overwhelming majority of supply chains while limiting costs when resorting to risk mitigation strategies in strategically important and highly concentrated ones.

Endnotes

1. We have made these indicators publicly available at https://forms.office.com/e/q0ZcVACFax.

2. The estimated output decline is 2.5% in the month of the shock (month 0 in Figure 2), 9% in the month following the shock (month 1), and 3.5% in the second month following the shock (month 2).

3. From a non-economic perspective, strategic importance also encompasses considerations such as the importance of a value chain for national defence, public health, and food security.

References

Baldwin, R and R Freeman (2022), “Risks and global supply chains: What we know and what we need to know”, Annual Review of Economics 14: 153-180.

Haramboure, A, J Guilhoto, G Lalanne and C Schwellnus (forthcoming), “Vulnerabilities in the semiconductor supply chain”, OECD Science, Technology and Industry Working Papers.

Irwin, DA (2022), “Globalization enabled nearly all countries to grow richer in recent decades”, PIIE Blogs, 16 June.

Javorcik, B (2020), “Global supply chains will not be the same in the post-COVID-19 world”, in R Baldwin and S J Evenett (eds), COVID-19 and Trade Policy: Why Turning Inward Won’t Work, CEPR Press.

OECD (2013), Interconnected Economies: Benefiting from Global Value Chains, OECD Publishing, Paris.

OECD (2021), Fostering economic resilience in a world of open and integrated markets, Report prepared for the 2021 UK Presidency of the G7.

Schwellnus, C, A Haramboure and L Samek (2023a), “Policies to strengthen the resilience of global value chains: Empirical evidence from the COVID-19 shock”, OECD Science, Technology and Industry Policy Papers.

Schwellnus, C, A Haramboure, L Samek, RC Pechansky and C Cadestin (2023b), “Global value chain dependencies under the magnifying glass”, OECD Science, Technology and Industry Policy Papers.

This article was originally published on VoxEU.org.