Liberals and women’s rights: past and present

Fleur de Beaufort is a Researcher and Patrick van Schie is the Director of the Telders Foundation, the Dutch Liberal Think Tank. In June 2019 they published a book about liberals and female suffrage in the Netherlands and Europe

A century of female suffrage in the Netherlands

This year the Netherlands is celebrating the fact that exactly one century ago women were granted the right to vote. Universal suffrage for Dutch women was realized two years after the same right was introduced for men, but while voting rights for men had been extended gradually over the preceding decades, no woman was entitled to vote until 1919.

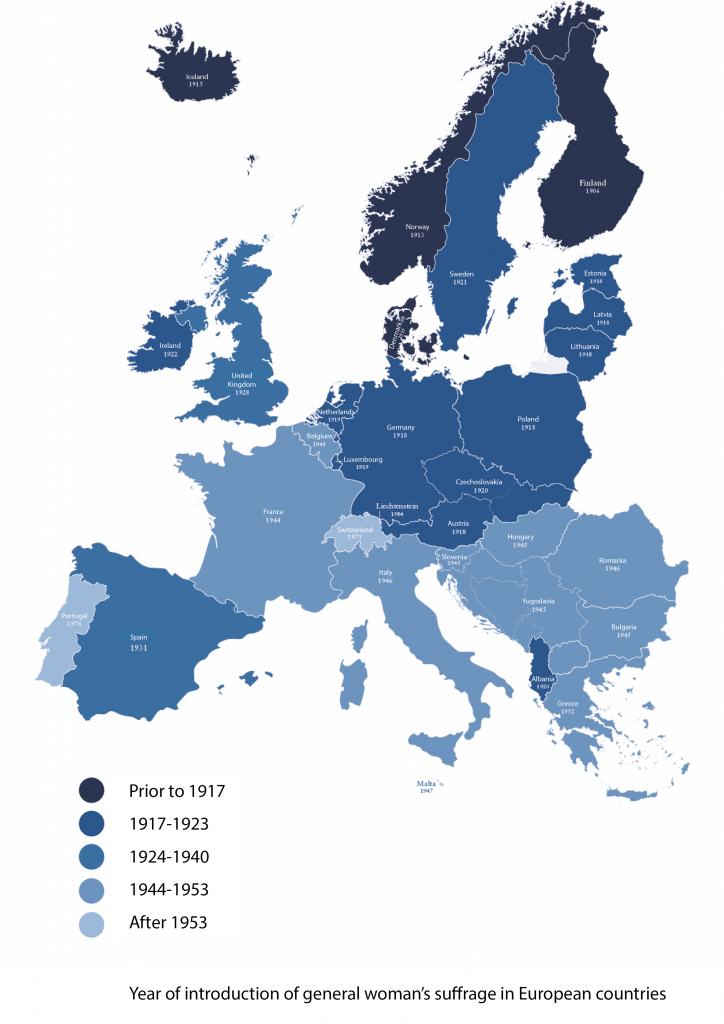

The Netherlands were not exclusive in incorporating women’s suffrage into law shortly after the end of the First World War; indeed, a wave of countries in the northern part of Europe did this during the same period (as did the United States and Canada). What did distinguish the Netherlands from those other countries was that it had been neutral during the war. The only other country to introduce women’s suffrage in this period after having been neutral was Sweden. There is no evidence of a direct impact of the war on the suffrage issue in either country.

In the Netherlands, however, there was another foreign event that changed the receptiveness of parliament to the issue. At the end of the First World War, and subsequent to the revolution in Russia in 1917, revolutions erupted in Central Europe. The Dutch socialist leader Troelstra tried to exploit this unrest by proclaiming revolution in the Netherlands. Although he met with more outright resistance than support, not only in parliament but in the country at large, the fear of revolution among Catholic parliamentarians caused them to change their stance on female suffrage from resistance to support.

Women – seen as more religious, more in favour of order and discipline, and with purer morals – were now welcomed as a firewall against revolution. This ensured the majority required in parliament that had been lacking in 1917, when general suffrage had been introduced for men, but when liberals and socialists had been the only parliamentarians willing to give the vote to women as well.

Although there had been several doubters among them, liberal politicians had been the staunchest proponents of female suffrage when it became an issue in Dutch politics at the end of the nineteenth century. Their arguments were mainly framed in terms of their belief that women would turn out to be just as capable as men of making sound political judgments, rather than in terms of equal rights.

As liberals, they were convinced that individuals – whether male or female – were sensible and thus capable human beings, so it would be to the disadvantage of society as a whole to deny it the influence of the female perspectives and insights.

Liberals and women’s suffrage in other European countries

In Scandinavia too, liberals were often the first to propose legislation to introduce votes for women; their earliest attempts in Finland date from 1897. Ten years later it was the Russian Tsar who gave the women of autonomous Finland (formerly part of the Russian Empire) the vote, almost as if by accident, making Finland the first European country with universal women’s suffrage at a national level.

In Denmark, there had also been liberal proposals in parliament before the First World War, but in the end a combined liberal-socialist government was successful in giving Danish women the vote from 1915 onwards. Likewise in Sweden, several liberal women’s suffrage bills adopted by the second chamber before the war had been rejected by the conservative-dominated Senate before a combined liberal-socialist government was able to introduce women’s suffrage in the aftermath of the Great War.

To be honest, liberals were not fierce supporters of women’s political rights everywhere. Looking at the map of Europe, one might be tempted to think that the late introduction of votes for women in predominantly Catholic countries such as France, Italy and Belgium was due to the resistance of conservative Catholic parties, but it was often the liberals and socialists who had combined their efforts to stop initiatives for women’s suffrage in these countries.

Take Belgium, for example, where a Catholic proposal for female suffrage just after the First World War was thwarted by the liberals, who feared that women could be more easily influenced by priests to vote for the Catholic party, which was already the strongest party in the country.

Even after the Second World War, when the liberals were no longer able to stop the introduction of women’s suffrage, a liberal minister succeeded in postponing it for at least one national election, meaning that Belgium lagged even further behind in this respect than it had already.

Belgian and southern-European liberals frequently acted opportunistically in obstructing female suffrage. They realized that equal voting rights were in accord with liberal principles, but they feared the electoral consequences. During the interbellum in France, members of the Radical (liberal) party who voted in favour in the Chamber of Deputies, repeatedly voted against once they became Senators; the Senate having the final vote.

Counterproductive activism in Britain

In Britain, liberal members of parliament were divided. In the early twentieth century, liberal backbenchers were mainly pro female suffrage, but a few important figures were either indifferent or openly opposed. Unfortunately for contemporary feminists, Prime Minister Asquith was one of the latter, and continually appeared to give other issues priority over women’s suffrage.

Nowhere in Europe did the struggle for women’s suffrage attract more activism and attention than in Britain. But the country was far from the first to introduce the measure, and when it was finally established in a bill in 1918 it applied only to about two thirds of the adult female population; the rest had to wait for another ten years.

Many British feminists tended (and still tend today) to blame the liberal government of 1906 onwards, particularly Asquith himself, but probably just as important was the role of the feminist movement itself, more specifically the ultra-radical faction led by Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughters.

The demands of feminists nowadays are noticeably the opposite of those of the female activists who fought for the right to vote more than a century ago

Their Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) – a rowdy but also tiny part of the British women’s suffrage movement as a whole – soon opposed every liberal politician, whatever the consequence (for instance the election of a staunchly anti-suffrage conservative as MP) or the position that the individual politician himself took on the issue.

This policy naturally alienated liberals of all hues, including liberal-minded women, and was not at all helpful in converting those opponents of female suffrage in the liberal ranks. Even more damage was done by the campaign of outright violence and vandalism started by the WSPU in 1908.

This included the breaking of shop windows and damaging of paintings in museums, attacks on liberal politicians, and setting fire to letter boxes, houses and churches. Such criminal acts were abhorred by the general public and made liberal politicians wary of appearing to give in to the violence.

Nowadays the actions of the ultra-radical suffragettes (who should not be confused with the moderate suffragists) are often portrayed as having laid the foundation for women’s suffrage in Britain, but in fact they were counterproductive. It is no coincidence that partial women’s suffrage was introduced in Britain more or less without incident in 1918, almost four years after the WSPU had suspended its violent activities.

As Asquith himself – now no longer Prime Minister – said, he was now able to vote for women’s suffrage without giving the impression that he had given in to violence and crime.

What kind of equality?

Whether liberals voted for or against the actual bills to introduce female suffrage, the great majority of them did not question the liberal credentials of the measure. Almost nobody reasoned that women were equal, let alone that they were the same as men in everything, but that liberalism itself as an ideology required that women deserved equal treatment and an influence of their own in the form of equal rights – including the vote – was almost undisputed.

Nowadays, however, the debate on equal rights for men and women sometimes seems to narrow down to equal opportunities and the presupposed lack of equal opportunities for women. Once women gained the right to vote, their actual presence in politics grew rather slowly.

In the case of the Netherlands, it took fifty years before the number of women in parliament exceeded 10% of the seats. From the 1970s, their number grew to 41% (62 seats out of 150) in 2010 – the highest percentage of female representation so far, as it declined to 35% in the most recent elections of 2017.

The picture is much the same at a local level, and current female representation in local government stands at 42%. In party politics, almost all leadership positions are filled by men, and the lists of candidates at elections continue to present more men than women to the voters.

Even though the position of prime minister or president has been held by a woman in a growing number of countries in recent years, the presence of women in politics continues to lag behind the participation of their male counterparts. The same can be said for board memberships and other leading positions in business, as well as government office.

For more than a decade this fact has motivated a number of people to call for a legally binding quota for board membership and political positions to solve this ‘problem’. In a free labour market – as is the general assumption among those in favour of quotas – women don’t share the same opportunities as men simply because they are women. Only legally binding quotas can end this inequality – or so the advocates of legislative action argue.

Before addressing the more fundamental arguments as to why legally binding quotas are – in our opinion – wrong, it might be good to focus on the ‘problem’ of female participation in politics and business. It is certainly true that the number of women in certain positions is lower than the number of men, but is it correct to blame inequality of opportunity for this, or could there be other causes?

Perhaps fewer women feel the ambition to be active in politics or in higher board positions. If this is the case, it is surely not a problem if this is the outcome of free individual choices. Women who do have the ambition to grow in certain positions should certainly have the same opportunities as men with these ambitions.

The much criticized ‘old boys’ network’ – whereby men hire other men they already know or recognize as their equal – can’t be the answer either, as women, once they are part of this network, exhibit the same behaviour.

The female board index (an annual overview of the presence of women in the executive and supervisory boards of Dutch listed companies) shows that the number of positions filled by women is growing faster than the number of women in these positions. If women are active in politics or in higher positions on boards it is more likely for them to receive new appointments and thus be active on several boards or in different political functions.

One could argue that there is no problem at all, as women who have the ambition, and (more importantly) are willing to make the choices in the organization of their private life that will be compatible with the requirements of demanding jobs, share the same opportunities as their male counterparts.

It is true that women are more often the ones who take care of the family, and choose to work part-time as a result, but this is hardly something in which the government should interfere. Liberals in particular will instinctively disapprove of government legislation to solve such a private matter.

As for positions in politics, women in general exhibit less interest in politics, something demonstrated, for example, in their party membership. Far more men are active members of political parties.

The demands of feminists nowadays are noticeably the opposite of those of the female activists who fought for the right to vote more than a century ago. Instead of equal rights as a starting point, the debate about demands for legally binding quotas centres on equality of outcomes.

In other words, if the outcomes of a process based on equal rights are unappealing, the government is urged to do something to influence these outcomes in a more desirable way, even if this involves inequality as a means to an end. So-called ‘positive discrimination’ means that the rights of one group (ie. men) are limited and ignored because the rights of another group (ie. women) are deemed to be more important.

For true liberals, however, it is not the fairness of the outcome of a process that counts, but the fairness of the process itself, based on certain key values such as individual liberty, responsibility and equal rights.

Moreover, liberals will always take the individual and their rights as the starting point, and generally feel great antipathy to the focus on groups and group rights that tends to be espoused by socialists and other left-wing politicians.