Benefits of the Capital Markets Union

Jean-Baptiste Gossé and Camille Jehle are Economists at Banque de France

The question of the optimal portfolio allocation seems particularly relevant for the EU, which exhibited a low level of corporate investment in some countries despite a large lending capacity in the last decade. Capital is supposed to flow from rich to poor countries, but this is not observed in practice (the Lucas Paradox) due to several sources of friction such as information asymmetry, market imperfections, or low institutional quality.

Although the creation of the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) eased access to equity markets (De Santis and Gerard 2006) and reduced transaction costs within the EMU (Haselmann and Herwartz 2010), a home bias persists in the euro area as regards trading stocks (Geranio and Lazzari 2019).

European institutions strive to reduce frictions and develop crossborder investments within Europe through the Capital Markets Union action plans, but the plans initiated in 2015 and 2020 have not yet produced the expected results (European Court of Auditors 2020).

In the context of the renewal of the European Commission this year, several recent propositions and statements launched the discussion on the priorities (eg. Letta 2024, Noyer 2024, Villeroy de Galhau 2024). Making full use of Europe’s capital markets will be key to mobilise the private investments needed to face common challenges (ECB 2024) and finance innovation while minimising the need for government support (Felke et al 2024).

Moreover, the lack of international diversification and integration can hinder the extent of risk sharing through portfolio incomes (Valiante 2016) and lower the capacity for innovation by restricting crossborder opportunities for higher risk projects.

A greater diversification of stock portfolios within the EU could have improved investors’ gains

In a recent paper (Gossé and Jehle 2024), we examine the benefits of stock diversification within the EU over the period 2012-23 using only available information when allocating the portfolio. According to standard finance theory, investors should be able to improve the performance of portfolios beyond the best-performing single asset by diversifying their portfolios (Markowitz 1952).

In our paper, we apply some modernised versions of this approach to stock market portfolios in order to determine whether European investors could have benefited from more crossborder diversification within the EU in the past years.

Under realistic assumptions (including limits on the share detained linked to the market capitalisation or GDP of each country), it would have been possible for investors to achieve significantly higher performances by reducing their domestic bias and investing more in other European countries, in particular in Central and Eastern European countries (CEECs).

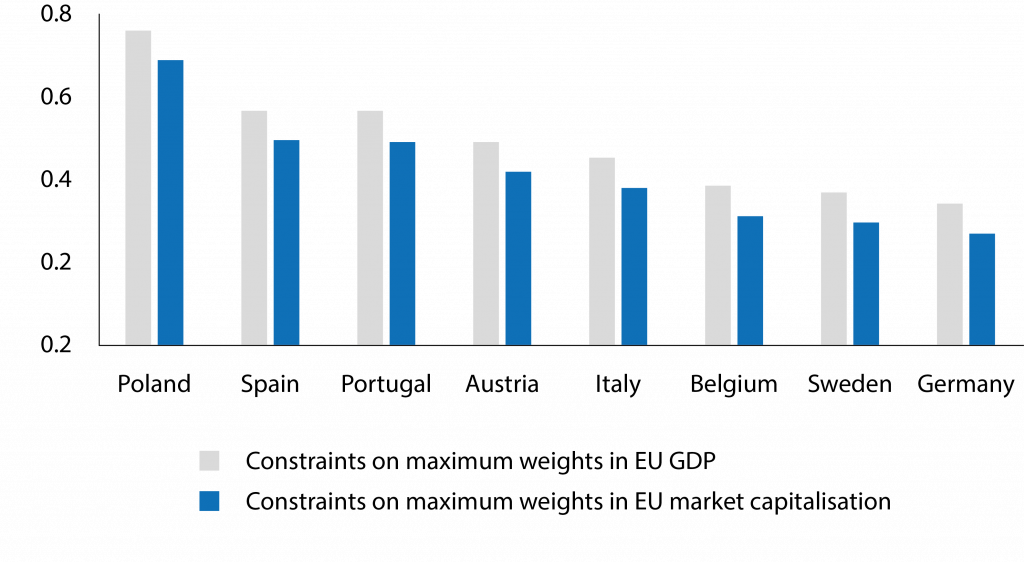

When redistributing intra-EU investments under market capitalisation constraints, improvements in performance are found to be significant (at the 10% level) for Austria, Belgium, Germany, Italy, Poland, Portugal, Spain, and Sweden, representing more than half of investments in listed shares within the EU.

Under realistic assumptions it would have been possible for investors to achieve significantly higher performances by reducing their domestic bias and investing more in other European countries

Figure 1. Delta Sharpe ratios: significant gains for eight countries

Note: The Sharpe ratio compares the return of a portfolio with its risk. The delta Sharpe is the difference between the annualised Sharpe ratios of the optimal portfolio and of the national realistic reference portfolio (see Gossé and Jehle 2024).

The diversification strategies would require increasing the size of equity markets in some countries such as CEECs, where they remain less developed (Lehmann 2020), and easing crossborder investment in the EU through initiatives such as the Capital Markets Union. The results can be interpreted as showing that financial development should be encouraged in CEECs to improve the potential gains of diversification.

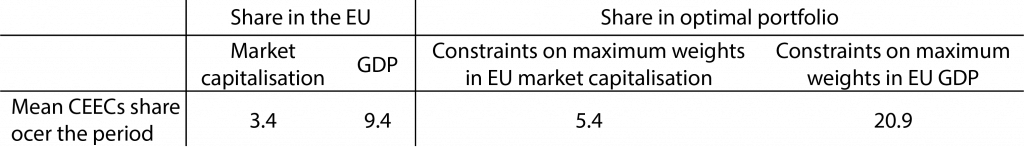

In particular, if the size of capital markets in terms of GDP were converging in EU countries, this would in most cases increase diversification gains and the share of CEECs would reach more than 20% (Table 1).

Table 1. Central and Eastern European countries’ share in EU market capitalisation, EU GDP, and optimal portfolios (%)

Note: Shares are expressed as a % of the total market capitalisation, total GDP, and the total investments made in EU stock markets by European investors (for optimal portfolios).

Diversification benefits are higher in low volatility periods

Since the period of analysis from 2012 to 2023 includes high volatility periods (European sovereign debt crisis, COVID crisis, and global energy crisis), we use the Volatility Index (VSTOXX) based on the real-time options prices of the EURO STOXX 50 in order to distinguish quintiles of volatility on the European equity markets.

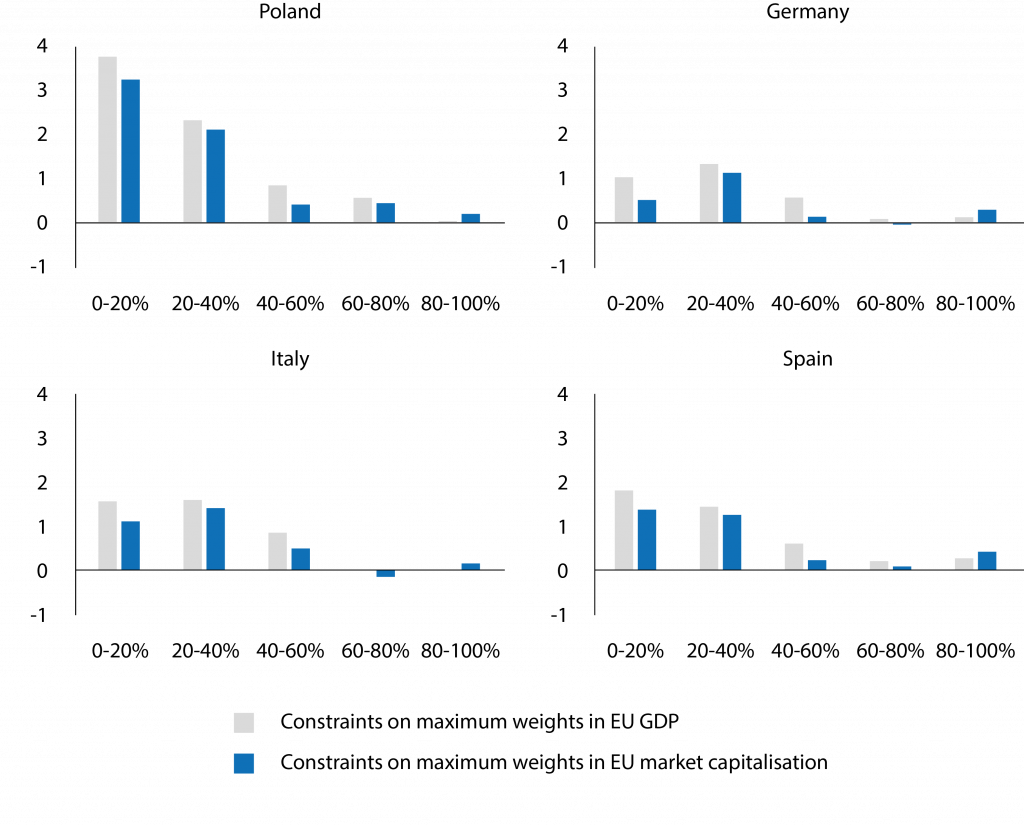

The optimal models perform much better during periods of lower volatility in the four major countries (Poland, Germany, Italy, and Spain) for which we found significant gains (Figure 2). Conversely, gains are very limited or almost nil during periods of high volatility.

Figure 2. Delta Sharpe ratios for the four largest countries exhibiting significant gains depending on the level of volatility

Note: The figures show the delta Sharpe ratio for the different quantiles of market volatility (measured with the VSTOXX).

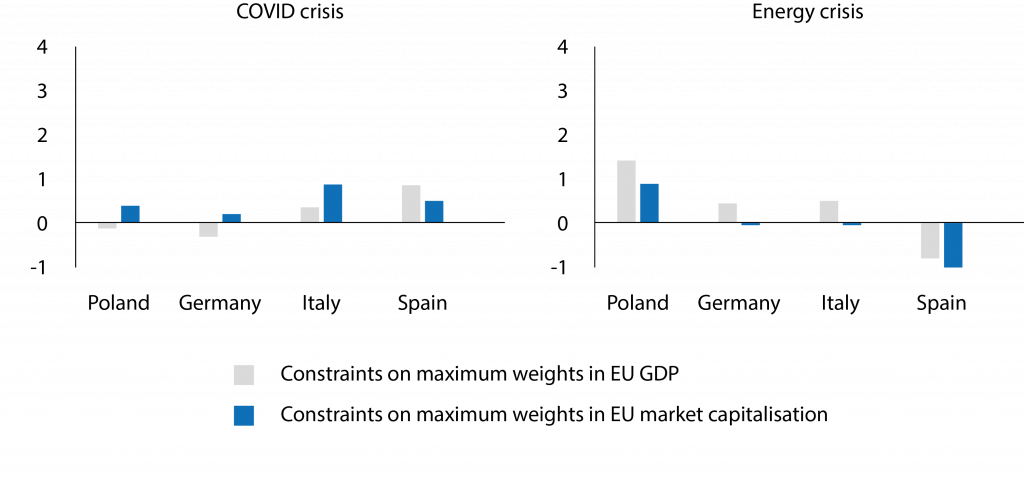

When analysing the delta Sharpe ratios during recent crises, we find similar results to the most volatile periods, with some exceptions (Figure 3). In Spain, the Sharpe ratios are much higher during the COVID crisis (similar levels as for the 40% less volatile periods in Figure 2) and much lower during the energy crisis. In Poland, the Sharpe ratios tend to be higher during the energy crisis compared to those observed for high volatility periods over the whole sample.

Figure 3. Delta Sharpe ratios during COVID and energy crises for the four largest countries exhibiting significant gains

Note: The figures show the delta Sharpe ratio for the quantiles of market volatility (measured with the VSTOXX) for the periods of high volatility (using the same 80% threshold as in Figure 1) following the COVID (March to July 2021) and energy crises (March to June 2022).

Diversification gains do not imply lower institutional quality or higher political risk

In the context of growing concerns about the quality of democracy and the intensification of geopolitical risk, investors may nevertheless be reluctant to increase their portfolios’ exposure to political risk. When instability linked to political risk increases, the optimal asset allocation can be revised in favour of home countries (Smimou 2014).

However, the mitigation of political risk is a central source of diversification gains (Attig et al 2023) and significant benefits can be achieved by including politically risky countries (Cosset and Suret 1995).

A high level of trust is particularly needed to attract investors in the stock market, which implies stronger investor protection and contract enforcement (Guiso et al 2008)1. Osina (2021) shows that rule of law, government effectiveness, and political stability are among the most important institutional factors determining gross capital flow dynamics.

Given that the level of trust in institutions to maintain a sound and stable financial system is identified as a major barrier to capital flows, we incorporate constraints on rule of law, voice and accountability, and political stability to ensure that diversification gains do not imply a decrease in the average institutional quality of investors’ portfolios. The aim is to obtain optimised portfolios that are equivalent in terms of institutional quality to the existing ones.

Significant diversification gains are confirmed for all countries except Sweden and Portugal (for the political stability index only for the latter)2. The share of CEECs is sometimes lower, especially when constraints based on GDP are applied, but always remains at much higher levels than in realistic reference portfolios.

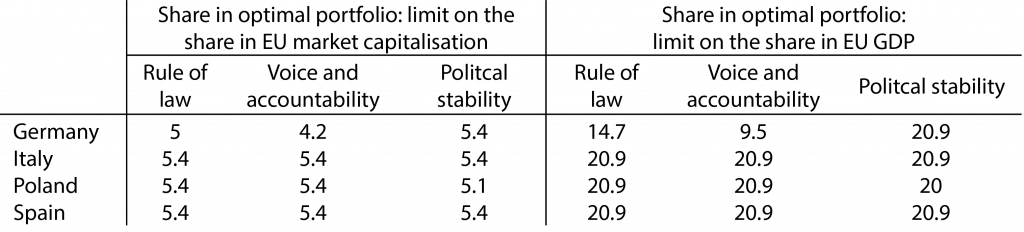

Investors therefore still benefit from significant diversification gains when investing more significantly in CEECs for an equivalent or higher average level of institutional indicators of their portfolios. Table 2 shows that for the four largest countries exhibiting significant gains, the mean share of CEECs would remain the same in most cases when constraining the level of institutional quality.

Table 2. Central and Eastern European countries’ mean share with constraints on institutional indicators for the four largest countries exhibiting significant gains

Note: Results are expressed as a percentage of the optimal portfolio.

Conclusion

In this column, we argue that a reduction in investment barriers could contribute to a better allocation of equity investments by reducing the home bias and further diversifying stock portfolios within the EU.

However, to avoid an imbalance between the demand for shares in markets that provide potential portfolio efficiencies and the supply of listed shares (McDowell 2018), it would be necessary to develop financial markets in Central and Eastern European Countries to a level more in line with the size of their economies.

This portfolio diversification would contribute to easing access to capital for CEEC firms, where the level of investment has decreased since the global crisis. Our results therefore tend to support, from the financial investors’ point of view, the benefits of deepening the Capital Markets Union and developing financial markets.

Endnotes

1. Trust is defined here as the subjective probability of being cheated by equity issuers and by institutions.

2. For these two countries, it was not possible to compute optimal portfolios when adding these constraints because of the very high levels of the average institutional indicators in their realistic reference portfolio.

References

Attig, N, O Guedhami, G Nazaire and O Sy (2023), “What explains the benefits of international portfolio diversification?”, Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money 83, 101729.

Cosset, JC and JM Suret (1995), “Political risk and the benefits of international portfolio diversification”, Journal of International Business Studies 26: 301-318.

De Santis, RA and B Gérard (2006), “Financial integration, international portfolio choice and the European Monetary Union”, ECB Working Paper 626.

ECB Governing Council (2024), “Statement by the ECB Governing Council on advancing the Capital Markets Union”, 7 March.

European Court of Auditors (2020), Capital Markets Union – Slow start towards an ambitious goal, Special Report No 25/2020, 11 November.

Felke, R, M Lichetta, N Philiponnet and M Verwey (2024), “Aim far, act now: Strengthening investment and economic integration to revitalise growth in the euro area”, VoxEU.org, 24 January.

Geranio, M and V Lazzari (2019), “Stress testing the equity home bias: A turnover analysis of Eurozone markets”, Journal of International Money and Finance 97: 70-85.

Gossé, JB and C Jehle (2024), “Benefits of diversification in EU capital markets: Evidence from stock portfolios”, Economic Modelling 135, 106725.

Guiso, L, P Sapienza and L Zingales (2008), “Trusting the stock market”, The Journal of Finance 63(6): 2557-2600.

Haselmann, R and H Herwartz (2010), “The introduction of the Euro and its effects on portfolio decisions”, Journal of International Money and Finance 29(1): 94-110.

Lehmann, A (2020), “Emerging Europe and the capital markets union”, Bruegel Policy Contribution No. 2020/17.

Letta, E (2024), Much More Than a Market. Speed, Security, Solidarity. Empowering the Single Market to Deliver a Sustainable Future and Prosperity for All EU Citizens, 18 April.

Markowitz, H (1952), “Portfolio selection”, Journal of Finance.

McDowell, S (2018), “The benefits of international diversification with weight constraints: A cross-country examination”, The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance 69: 99-109.

Noyer, C (2024), Developing European capital markets to finance the future, April.

Osina, N (2021), “Global governance and gross capital flows dynamics”, Review of World Economics 157(3): 463-493.

Smimou, K (2014), “International portfolio choice and political instability risk: A multi-objective approach”, European Journal of Operational Research 234(2): 546-560.

Valiante, D (2016), “Europe’s untapped capital market”, VoxEU.org, 13 March.

Villeroy De Galhau, F (2024), “From a Capital Markets Union to a genuine Financing Union for Transition”, Speech Eurofi – Ghent, 23 February.

This article was originally published on VoxEU.org.