Geopolitical shifts and their economic impacts on Europe

André Sapir and Jacob Funk Kirkegaard are Senior Fellows, and Jeromin Zettelmeyer is the Director, all at Bruegel

Executive summary

Over the last decade, Europe has suffered from the decay of the post-war international order, economic coercion from both China and the United States, and aggression from Russia. This contribution puts these changes into a historical context, examines their short-term consequences, develops scenarios for 2030-2035 and uses these to draw out the policy implications for the next one to five years.

The short-term output impact of tariff and policy uncertainty since the beginning of the second Trump Presidency is expected to be moderate. However, Europe faces very high risks. Plausible short-term dangers include: a collapse of the US bond market; escalation of Russian military aggression against Ukraine or the European Union directly; a fiscal crisis triggered by a populist election victory in a high-debt euro area member; or a trade shock triggered by increasing tensions between the US and China and/or hostile Chinese actions in East Asia.

We develop three benchmark scenarios for the world in 2035, all of which involve continued US-China rivalry and greater multipolarity than in the past:

1. A further retreat from, or dismantling of, international cooperation, with continuing protectionism in the US and minimal global public goods.

2. A three-bloc world involving China- and US-led blocs alongside a non-aligned set of countries, with the provision of international public goods within, and partially between blocs.

3. A new multilateral order, with international cooperation over the provision of global public goods.

Actual outcomes could consist of combinations of these scenarios or variants of them. Scenario 1 would be least desirable for the EU, most countries individually and countries collectively, while scenario 3 would be most desirable. In scenario 2, Europe’s decision to align with the US or to choose non-alignment would depend on whether the US acts in a benevolent or coercive manner.

Short to medium term policy must both prepare Europe for adverse future scenarios and contribute to greater international stability and cooperation. This requires policies that increase Europe’s strategic autonomy from the two superpowers, both for its protection and to increase its bargaining power.

The policy focus should include much greater defence, tech and financial autonomy from the US, a far more resilient and integrated energy system, secure access to critical minerals and a fiscal framework that gives greater flexibility to low-risk countries.

Internationally, Europe should defend and promote the reform of the rules-based international order by forming coalitions with other countries from the Global North and some from the Global South. The two priority areas should be trade policy and climate policy.

1 Introduction

Geopolitical tension and uncertainty are staples of history, even in a period of relative international order and prosperity, as Europe and most of the world have enjoyed since the end of the Second World War. But the rise in tensions over the last decade, and particularly since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 and the return of President Trump to the White House, seems different from anything that European and other advanced democracies have experienced since the late 1940s. Unlike previous geopolitical episodes, the international order itself is now being challenged.

And unlike the 1971 collapse of the Bretton Woods system, which was also a major challenge to the existing order, today’s shift is not a reaction to the economic unsustainability of the previous regime. Rather, it is the manifestation of deeper trends, including the rise of China, the failure of democratic transition in Russia and increasing polarisation in many Western democracies. It is polarisation that has led to a drastic political and policy change in the United States, with profound consequences for the postwar system.

We argue both that the world is at the beginning of a new era that will challenge the foundations of European prosperity, and that the future is wide open and Europe may be able to shape it. We develop three scenarios to give a sense of both threats and opportunities.

In terms of threats, policies that enhance European strategic autonomy must be emphasised to a much greater degree than in the past. But Europe must not just create more autonomy for itself – it should also put it to the best possible use for the global rules-based order.

The remainder of the paper is divided into three parts. Section 2 recalls the main phases in the evolution of the international economic order since 1945, describes the current geopolitical state of affairs and summarises the short-term economic effects on Europe of recent US policy shifts. Section 3 presents three geopolitical scenarios that will confront Europe in 2030-2035. Section 4 describes Europe’s policy choices in relation to these scenarios. The paper ends with some conclusions.

2 The geopolitical state of affairs and its economic effects on Europe

2.1 The evolution of the multilateral system, 1945-2008

The postwar economic order, with the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank and the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) as the three central institutions, was created between 1944 and 1947 by the winners of the Second World War to foster postwar economic cooperation and to prevent a return to the economic nationalism of the 1930s. But what was intended as a new global economic order did not become truly global until the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1990.

2.1.1 The Cold War period

During the Cold War, running from 1947 to 1989, the world was divided into two spheres, east and west, which were political rivals with minimal economic relations between them. Countries in both spheres belonged to the global political institutions created after the Second World War under the leadership of the US, the United Nations and its specialised agencies. But only those in the western sphere – and two countries that later founded the non-aligned movement, India and Yugoslavia – joined the new economic institutions1.

Most developing countries, which were previously colonies of western countries, became and remained non-aligned after independence, maintaining a degree of political distance from the two spheres, while gradually joining the GATT, IMF and World Bank.

During this period, the world was bipolar, with two superpowers: the US as ‘leader of the free world’ and the Soviet Union as the main country in the communist camp, though increasingly in competition with China. The western camp lived in a ‘liberal international order’ in which crucial international public goods in trade, finance and defence were provided by the United States acting as its ‘benevolent hegemon’.

Multilateralism mostly prevailed within the western sphere, but not when it clashed with US interest, as with the ‘Nixon shock’ in August 1971, when the US president ended the Bretton Woods system of fixed but adjustable exchange rates by taking the dollar off the gold standard, and introduced a 10 percent tariff surcharge on all dutiable imports2.

The import surcharge was meant to put pressure on the main US partners to revalue their currencies against the dollar, which they did under the December 1971 Smithsonian Agreement of December 1971, in the hope of preserving the Bretton Woods system. This hope was dashed in 1973, after the US further devalued the dollar, forcing major currencies to float against the greenback and each other.

Another instance of US unilateralism during this period was Section 301 of the 1974 US Trade Act, which allows the US administration to unilaterally (ie. without recourse to the GATT dispute settlement procedure) address ‘unfair foreign practices’ through investigations, negotiations and, if necessary, the imposition of tariffs or other trade restrictions. Section 301 is the only US statute that permits the US administration to adopt unilateral trade sanctions on economic grounds. Two other statutes – Section 232 of the 1962 Trade Expansion Act and the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) of 1977 – also permit the US administration to unilaterally impose trade sanctions on certain countries, but on national security grounds.

Short to medium term policy must both prepare Europe for adverse future scenarios and contribute to greater international stability and cooperation. This requires policies that increase Europe’s strategic autonomy from the two superpowers, both for its protection and to increase its bargaining power

2.1.2 The rise and fall of hyper-globalisation, 1990-2008

With the 1989 collapse of the Berlin Wall and the end of the Soviet Union in 1991, liberal democracy appeared to have “triumphed as the final form of human government” (Fukuyama 1992). In geopolitical terms, this meant that all countries could now join the liberal international order.

In 1992, Russia joined the IMF and the World Bank. The next year, it applied to join the GATT but had to wait until 2012 to become member of its successor, the World Trade Organisation (WTO), created in 1995. The People’s Republic of China had already joined the IMF and the World Bank in 1980, and the WTO in 2001.

With China and Russia taking major steps to liberalise their economies, it looked as if Fukuyama’s “end of history” (Fukuyama 1992) was approaching, not only in an ideological sense but also geopolitically. Economic liberalisation in the former eastern sphere, in India and other large developing countries, together with the rapid introduction of information technologies created ‘One World’ with opportunities for more people in more places to compete, connect and collaborate more than ever.

This ushered in a period of truly global trade and investment integration – often referred to as ‘hyper-globalisation’ – dominated by purely economic incentives and global value chains (GVCs), with little or no geopolitical constraints (see, for instance, Antras 2020).

This period has been described as the unipolar world, with the United States commonly viewed as the sole superpower. It worked fairly well for nearly two decades. The US continued to act as a ‘benevolent hegemon’ and the liberal international order thrived, with democracy spreading around the world, the creation of the WTO as the lynchpin of the rules-based multilateral system, and hyper-globalisation delivering rapid economic growth to old and mostly new parts of the world.

However, according to geopolitical realists such as Mearsheimer (2019), the liberal international order was bound to fail because it contained the seeds of its own destruction. First, the spread of western-style democracy produced a nationalist backlash in some countries, including China and Russia.

Second, hyper-globalisation produced faster growth but also contributed to greater income inequality and financial instability, both of which contributed to a populist backlash in advanced countries, especially the US, after the Great Financial Crisis.

Third, hyper-globalisation was particularly helpful in promoting faster growth in China and other export-oriented developing countries. The “rise of China…along with the revival of Russian power … brought the unipolar era to a close” (Mearsheimer 2019, p. 8).

The decline of the liberal international order and the ‘return of history’ ushered in the third and current phase in the post-Second World War international system. As anticipated by Kagan (2008 p. 4), “The end of the Cold War did not bring the end of history, but rather a return to a historical norm: competition among great powers.”

2.2 The return of Great Power competition and economic nationalism in the United States

Analysts disagree on how to describe the new era. Kagan’s ‘return to great power competition’ is one way. Others refer to it as the ‘post-post-Cold War era’3, as an ‘era of fragmentation’ (for instance, Clavijo 2024) or simply as a ‘multipolar era’ replacing the previous unipolar period4.

The problem with these labels is that they underplay what (in addition to the rise of China) has emerged as a defining feature of the last decade: the gradual withdrawal of the US from its role as ‘benevolent hegemon’. This shift accelerated with President Trump’s push to blatantly violate post-Second World War rules and norms, including with his ‘reciprocal’ tariffs (which are in fact unilateral rather than reciprocal and violate the cornerstone of the GATT/WTO regime, which forbids countries from discriminating between their trading partners).

Trump has also launched assaults against international law, democratic norms and institutions. One way to describe the present United States is as a ‘coercive hegemon’, though the term ‘hegemon’ itself does not fit well with the new multipolar age. In fact, the contradiction between the two – multipolarity and hegemony – describes well the current geopolitical situation, which is in a state of flux.

Though the US is not the hegemon it was during the unipolar post-Cold War period, or even the bipolar Cold War era, it retains exceptional features that set it aside from other major powers including China and the European Union.

It is easy to minimise the role of the US in world trade by noting that it accounts for less than 15 percent of global trade in goods and services (excluding intra-EU trade), and that therefore the rest of the world can and should continue to organise itself according to WTO norms and rules, which the US is now disregarding. But the US has demonstrated that it can coerce many of its trading partners, including the EU, to accept bad deals.

Typically, such deals involve accepting unilateral US tariff hikes and also opening up domestic markets and committing to buy products preferentially from the US (against the interests of trading partners and against WTO rules) as the price for keeping US tariffs lower than threatened by President Trump, and, above all, for retaining aspects of US security protection.

This continuing US power derives from its superiority in four areas: economy, finance, technology and military. China is the only country that partly rivals the US in all of these areas, except finance. While the EU has strengths in some of these areas, it is clearly dominated by the US, and increasingly China.

The US remains the largest economy (26 percent of world GDP in 2024 at market exchange rates), which partly explains why it is also the world’s largest importer of goods. Also, of course, the US now specialises mainly in the production of services, and therefore tends to export services and import goods – the opposite of China, the world’s second largest economy (on par with the EU, both accounting for 17 percent to 18 percent of world GDP at market rates), which specialises in the production of goods and therefore tends to export goods and import services.

Although the US is increasingly challenged by China for the top place in the GDP league (and has already been displaced by China when the comparison is made using purchasing power parity exchange rates), it remains unparalleled in finance. The US accounts for roughly 50 percent to 60 percent (depending on the exact year) of global equity market capitalisation, and 40 percent of bond market capitalisation, far ahead of the EU and China.

The US dollar continues to occupy a dominant position, accounting for 60 percent of international reserve holdings in currencies, 45 percent of global trade invoicing and 90 percent of foreign exchange transactions, again far ahead of the euro and renminbi.

In technology, although the US share of global research and development spending has been declining for decades, the US retains overall leadership. China is making rapid progress and has overtaken the US in some critical areas. As Draghi (2024) noted, Europe also has major technological capabilities, but is weak in digital technologies, such as artificial intelligence, the internet of things and quantum computing.

US technological leadership rests on the strength of its private sector, which benefits from a strong innovation ecosystem that includes top universities able to attract student and faculty talent from all over the world and easy access to venture capital.

For instance, in 2023, the US had twice as many active unicorns (startup companies valued at over $1 billion) as the EU and China combined. However, the policies of the Trump administration on research and universities threaten to deliver a blow to the US innovation ecosystem and weaken its technological leadership.

In the military field, US dominance comes partly from the fact that it has accounted for roughly 40 percent of global military expenditures for several decades, far more than its share of global GDP. This has allowed the US to finance the research, development and purchase of sophisticated weaponry, to maintain military bases and troops in every region of the world, and to lead alliances such as NATO, making it the ‘policeman of the world’, even if this role is increasingly contested, especially in Asia by China.

According to Carlough et al (2025), the US maintains 31 permanent bases and has access to 19 additional sites in Europe (the EU plus Norway, Turkey and the United Kingdom). Carlough et al (2025), citing official sources, also report that, in early 2025, the US had nearly 84,000 US service members in Europe, down from over 100,000 in 2022, after the full invasion of Ukraine by Russia.

All this sums up to an international system in flux and disorder. In trade, the WTO has been greatly weakened by the willingness of the US – the world’s largest importer of goods – to openly violate international rules, which have become partly outdated in any case because the role of the state in China, the world’s largest exporter of goods, is incompatible with the spirit (but not the letter) of the liberal economic order that the WTO represents.

But, so far, the rules-based multilateral system has held up. Apart from the US, other WTO members have continued to play by the rules, with one major exception, with many, including the EU, granting preferential access to (some) imports from the US, as part of the deals they have struck with President Trump to avoid the imposition of higher reciprocal tariffs.

In money and finance, where there has been no formal international system since the end of the Bretton Woods system in 1973, there is nonetheless a global order. One element is the role of the US dollar in international payments and as a store of value. Some Trump administration policies, such as the promotion of dollar-based stablecoins, could further enhance this role5.

Others, such as the administration’s lack of concern about fiscal sustainability, and words and actions that undermine the independence of institutions such as the Federal Reserve and the Bureau of Labor Statistics, could undermine the dollar’s international role (see section 2.3.2).

The other element in maintaining global order has been international organisations including the IMF, World Bank, Bank for International Settlements (BIS) and the Financial Stability Board (FSB), which have played important roles in coordinating international efforts to maintain financial stability or restore it during crises.

Although the Trump administration announced that it would review US membership of the IMF, World Bank and other international organisations, Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent has stated that the role of the US is rather to “push them to accomplish their important mandates” and focus on their “core mission”6.

The EU has played a constructive role by setting up the euro and ensuring its stability, but the absence of a “genuine Economic and Monetary Union”, as advocated more than a decade ago by Van Rompuy (2012), limits its ability to play a bigger international role.

Finally, in the area of international security, the fragile world order has been greatly damaged by Russia’s full invasion of Ukraine in 2022. This is rightly viewed as a painful wake-up call and turning point by Europeans, especially in the context of President Trump’s questioning of NATO, though for some others (including China and India), war in Ukraine has been no more damaging to the world order than the 2003 invasion of Iraq by the United States (with the support of the United Kingdom, Australia, Poland and others), which was also not authorised by the UN Security Council.

Meanwhile, in the Middle East, conflict has raged again since 2023, and Taiwan faces continuous threat of an invasion or a severe blockade by China. In all these theatres, the role of the US as ‘global policeman’ has receded, and no other power has filled its place. The EU, which is struggling with its own security, is not a candidate – except in Ukraine.

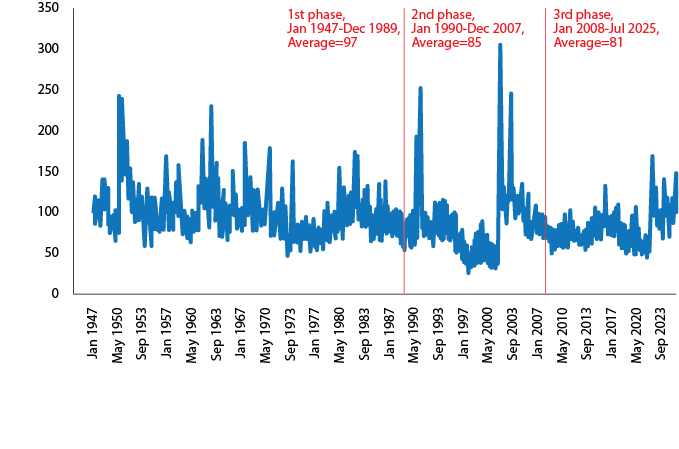

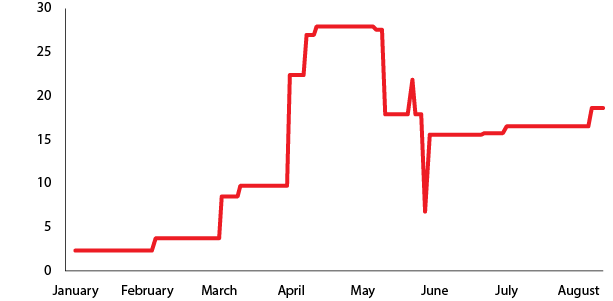

One way to compare the new era of armed conflict and economic nationalism with earlier periods is through indices designed to quantify geopolitical risks and policy uncertainty. The global Geopolitical Risk Index (GPR), which focuses mainly on military risk, is currently slightly below its level during the post-Cold War period, despite the Russia-Ukraine war and the latest episode of conflict in the Middle East (Figure 1)7.

Figure 1. Geopolitical risk index, 1 Jan 1947 to 1 Jul 2025, average by geopolitical phase

Source: Bruegel based on Caldara and Iacoviello (2022). Data downloaded from https://www.matteoiacoviello.com/gpr.htm.

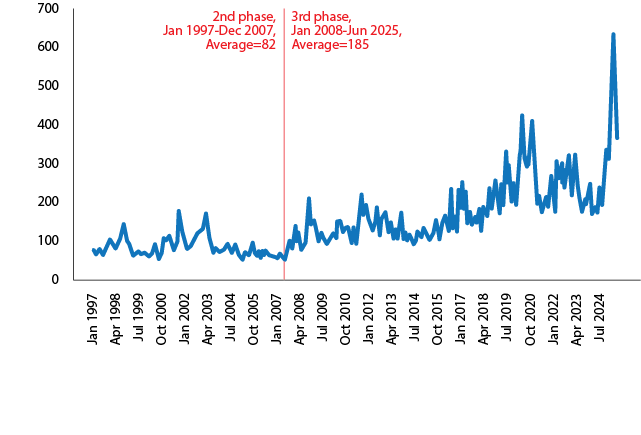

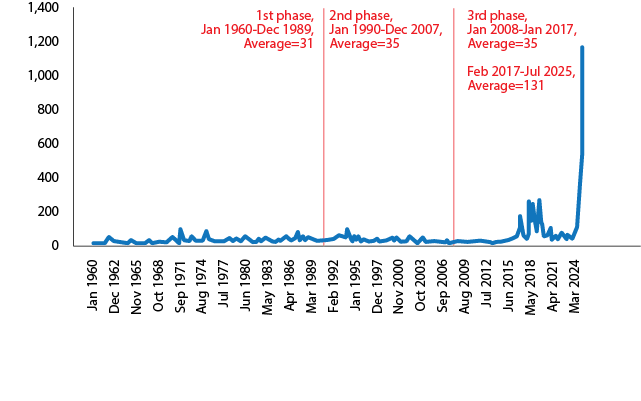

By contrast, the global Economic Policy Uncertainty Index (EPU) and Trade Policy Uncertainty Index (TPU) have moved up since 2017, reaching their highest ever level immediately after so-called ‘liberation day’ (1 April 2025), when President Trump announced the imposition of ‘reciprocal’ US tariffs on imports from trading partners (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2. Economic policy uncertainty index, Jan 1997 to Jun 2025, average by geopolitical phase

Source: Bruegel based on Davis (2016). Data downloaded from https://www.policyuncertainty.com/global_monthly.html.

Figure 3. Trade policy uncertainty index, Jan 1960 to Jul 2025, avg. by geopolitical phase

Source: Bruegel based on Caldara et al (2020). Data downloaded from https://www.matteoiacoviello.com/tpu.htm.

2.3 Short-term economic effects on Europe

The acceleration of the shifts described in the last section in President Trump’s second term is at time of writing affecting the European economy through three main channels: a sharp rise in US tariffs, policy uncertainty and fiscal policy. These impact the EU directly and indirectly, via their impact on the United States (which will remain the EUs largest trading partner in the foreseeable future, tariffs notwithstanding). Monetary policy on both sides of the Atlantic is seeking to modulate the impact of these policy shocks. In addition to baseline effects, there are substantial downside risks.

2.3.1 Baseline effects

Tariffs. US effective import tariffs have gone from 2.4 percent at the end of 2024 to almost 19 percent in mid-August 2025 (Figure 4). Imports from the EU now face a baseline tariff of 15 percent, with some products (steel and aluminium, copper and cars) facing higher tariffs at the time of writing, and a yet-to-be defined set of ‘strategic products’, to which lower or zero tariffs will apply8.

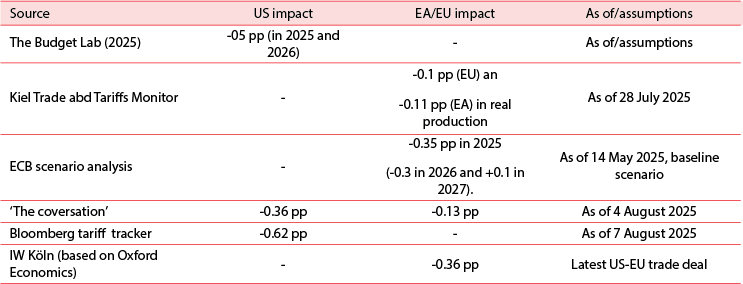

Estimates of the 2025 and 2026 GDP impact of these tariffs on the US are larger than the impacts on the EU, ranging from -0.35 percent to -0.6 percent of GDP (relative to the preexisting baseline), while the impact on the EU is estimated at -0.1 percent to -0.35 percent of GDP (see Annex Table 1). While the US economy is suffering a generalised negative supply shock via import prices, the EU is suffering a negative demand shock that affects about 20 percent of its goods exports (worth 3 percent of EU GDP in 2024)9.

Furthermore, the 15 percent levy is at the low end of the range of reciprocal tariffs the US has imposed on most other major exporters, implying that it may offer the EU a gain in market share relative to other exporters, which may compensate for some of the losses relative to US producers.

Figure 4. United States average effective tariff rate

Source: Bruegel based on The Budget Lab (2025).

Policy uncertainty. While some of recent rise in policy uncertainty (Figures 2 and 3) is transitory (as the policy regime emerging from the stop-and-go announcements of the US administration becomes clearer), some may be permanent, as erosion of the rules-based order and independent institutions in the US creates more room for executive discretion.

Notwithstanding the recovery in the US stock market after declines when the US tariff hikes were announced on 1 April, there is evidence that policy uncertainty has dampened investment in the US. Greater volatility and weaker growth in the US hurts the EU through the export channel and might strengthen investment in the EU in relative terms.

Fiscal policy. While the Trump administration’s so-called One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA), signed into law on 4 July 2025, is estimated to be roughly neutral over the next ten years compared to an extension of current US fiscal policy (which was and remains on an unsustainable path)10, it is expansionary in the short term because the spending cuts envisaged in the bill are backloaded. According to IMF estimates, the OBBBA will raise the US deficit by about 1.5 percent of GDP in 2026.

Fiscal policy in the EU has been affected mainly through the impact of policy shifts on defence spending. In March, the European Commission (2025b) announced that EU members during 2025-2028 would be allowed to debt-finance an increase in defence spending by up to an additional 1.5 percent of GDP per year relative to 2021 levels, if they request the national escape clause (NEC) under the EU fiscal rules.

By end-April 2025, 16 EU countries had made such requests11. According to the European Commission (2025c), based on “credibly announced and sufficiently detailed measures”, additional defence expenditures announced by 30 April 2025 will amount to 0.1 percent of EU GDP in 2025.

The June NATO summit triggered further announcements for 2026 and beyond, while the German medium-term fiscal-structural plan, published in July, envisages an increase in the country’s fiscal balance by about half a percent of GDP relative to the European Commission’s baseline for both 2025 and 2026. On this basis, the combination of higher defence spending and additional fiscal expansion in Germany could add fiscal stimulus in the order of 0.2 percent to 0.4 percent of EU GDP during 2025-2026.

Importantly, this stimulus is set against a baseline that would otherwise be contractionary, as many EU countries had begun their adjustments under fiscal rules enacted in 2024, leading to net neutral or slightly expansionary fiscal stances in 2025 and 2026.

Monetary policy. The combination of higher tariffs and policy uncertainty has created a difficult task for the Federal Reserve, which needs to manage a negative supply shock in an environment of high demand uncertainty. With US inflation likely to be above target, it has opted to leave the federal funds rate unchanged at 4.25 percent to 4.5 percent since December 2024.

In contrast, the European Central Bank’s task has been comparatively simple: with euro area inflation declining below 2 percent and slowing external demand, because of higher US tariffs and appreciation of the euro-dollar exchange rate, it has lowered its deposit interest rate. However, markets view a Federal Reserve interest rate cut in September as likely and expect a further cut by the end of 2025 and two cuts by mid-2026.

In contrast, markets are currently pricing in no further cuts from the ECB this year and are unsure about a cut in the first half of 202612. The joint impact of policy shocks and policy uncertainty is reflected in short-term output expectations.

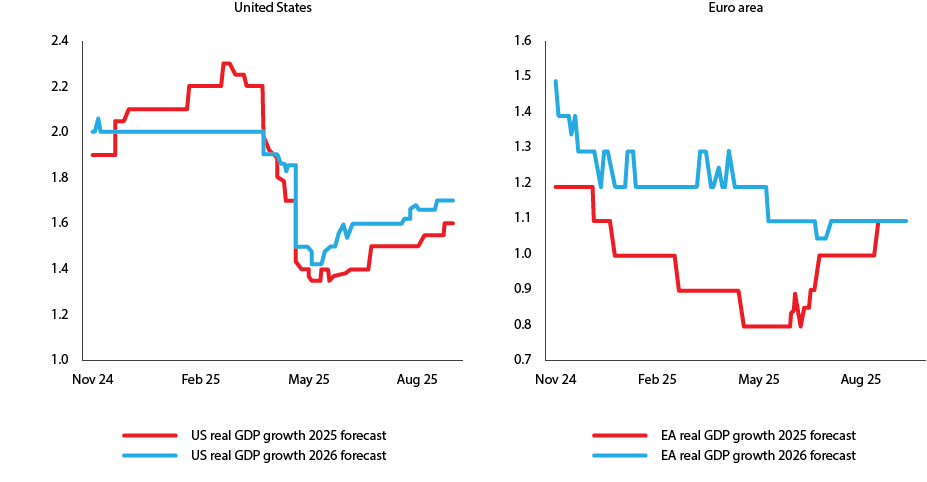

Figure 5 shows the evolution of median forecasts of private sector economists surveyed by Bloomberg for both the US (panel a) and the euro area (panel b). The purple lines show forecasts for 2025 real GDP growth; the light blue lines show forecasts for 2026. Dates on the x-axes indicate the time of the forecasts.

Since Trump’s second inauguration in January until early September 2025, the 2025 median growth forecast for the US has dropped by 0.50 percentage points, from 2.1 percent to about 1.6 percent, while the euro area median forecast dropped by just 0.1 percentage points, from 1.2 percent to 1.1 percent.

In the interim, forecasts for 2025 have undergone large swings, particularly in the US, where exuberance in the first months of the new administration was followed by a large drop in output expectations in April, when the extent of Trump’s tariff hikes became clearer, and eventually a modest recovery. US output expectations for 2026 have gone through a similar cycle, albeit of smaller amplitude (Figure 5, left panel).

For the euro area, the 2025 forecast decline in the first half of 2025 has been more gradual than in the US, while the June-August recovery was steeper, likely reflecting a combination of monetary and fiscal policy easing, and the trade agreement with the US at the end of July.

At time of writing, forecasters expect modestly higher US growth in 2026 than in 2025, perhaps reflecting expected fiscal stimulus and monetary easing. Euro area output in 2026 is expected to be unchanged from 2025.

Figure 5. US and euro area short-term forecasts of annual real GDP growth (percent)

Note: Latest observation 04/09/2025.

Source: Bruegel based on Bloomberg Economist Survey (median response).

2.3.2 Risks

While expected EU and US economic performance for both 2025 and 2026 is sub-par, baseline forecasts remain relatively benign – far from a recession in either the US or the euro area. Nevertheless, it is easy to imagine far worse outcomes, even in the relatively short term (2025-2027). We focus on four.

A collapse of the US bond market, triggered by one or several of the following: (1) a sense that the US deficit is out of control, as political majorities in the US make fiscal adjustment impossible in the foreseeable future; (2) a sharp rise in inflation expectations; (3) a loss of faith in the quality of US economic data, particularly inflation and labour market data, triggered by Trump’s assault on institutions.

An escalation of Russian military actions against Ukraine or the EU directly. This could take several forms: significant further loss of territory in Ukraine, leading to a new refugee wave; an acceleration of Russia’s hybrid campaign against the EU, targeting EU government institutions, critical infrastructure and other economic assets; or even a direct Russian military attack on one or several EU countries.

In the case of a direct military attack, the defence of Europe would become existential, testing NATO and EU unity. Russian military or hybrid gains short of a direct attack on the EU, however, may hurt the EU particularly through their political and economic knock-on effects.

These include nationalist populist backlash in the EU – hurting mainstream parties and eroding the consensus around additional assistance to Ukraine – and sharp drops in EU consumer and investment confidence, depressing output, increasing fiscal stress and possibly prompting a return of the fiscal-banking ‘doom loop’ in some EU countries.

A fiscal crisis in the euro area triggered by a populist election victory in a high-debt member state. With the government of the country in question unable or unwilling in this scenario to undertake fiscal adjustment in response to a loss in market confidence, EU crisis mechanisms may fail to work. The resulting debt crisis would throw the euro area into turmoil and raise questions about the sustainability of the common currency, as it did during 2010-2012.

A trade shock triggered by increasing tensions between the US and China and/or hostile Chinese actions in East Asia. Global supply chains could be disrupted either by an interruption of shipping linked to hostilities in East Asia, or by export bans on all critical minerals to any nation deemed to take ‘hostile economic actions’ against China.

All EU countries would be included in China’s immediate export ban. The EU would be faced with a prolonged economic downturn from the de facto end of freedom of navigation in the high seas in a vital part of the world and the severance of important global sea lanes, and would be denied access to critical minerals crucial to its industrial economy.

These shocks could be amplified in two ways. First, crisis scenarios may overlap (for example, policy paralysis arising from a populist victory and the priority of repelling Russian aggression). Second, several countries could be pushed to the fiscal and social breaking point.

The accumulation of crises since 2008 has left profound economic, political and social marks on the EU, US and other advanced countries. One measure of this is the level of public debt. In 2007, at the end of the post-Cold War period, debt-to-GDP ratios stood between 60 percent and 65 percent on average for the EU and euro area, with substantial differences between countries. The US ratio was similar.

By 2024, debt-to-GDP ratios had increased by more than 20 points for the EU/euro area, with a big increase in the dispersion between countries. In countries including Denmark, Germany and the Netherlands, the debt ratio remained around or well below 60 percent, while it increased by around 50 percent of GDP or more in Finland, France, Spain and the US (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Debt-to-GDP ratio in 2007 and 2024 (percent)

Notes: Solid black line indicates a debt-to-GDP ratio of 100 percent. Countries are ranked in increasing order of the difference between the debt ratio in 2024 and 2007.

Source: Bruegel based on IMF (WEO).

According to Darvas et al (forthcoming), stabilisation of the debt ratio over the long term will require fiscal adjustment of about 6 percent of GDP in the US, 5 percent of GDP in France and about 3 percent to 4 percent of GDP in Italy, Spain and Belgium. Although they have much lower debt ratios, several central and eastern European countries are also under high pressure to adjust over the medium term on account of very high deficits.

Add to this the additional cost of defence in the face of the new geopolitical reality, plus the costs of ageing populations and climate change (mitigation and adaptation), and it becomes clear that public finances are in a very difficult place in many EU countries and the US.

We assess the policy implications in section 4, after examining three geopolitical scenarios for the period 2030-2035 in section 3.

3 Three geopolitical scenarios for the coming decade

This section discusses three contrasting geopolitical scenarios for 2030-2035 that share two common features: the world will be more multipolar than today, with no country willing or able to play the role of global hegemon providing overall insurance to the system; and the US-China geopolitical rivalry will persist. Multipolarity will increase because the number of major powers will rise. By 2030-2035, there will be a dozen major powers falling into three tiers:

Superpowers: China and the US. There is much speculation among analysts and policymakers about the economic, military and technological trajectories of the two countries over the next five to ten years, and whether the US will retain its lead in some or all of these areas or be overtaken by China13. But there is consensus that in this timeframe, China and the US will remain the world’s only superpowers.

Other (potential) great powers: Russia, the EU and India. Besides China and the US, only Russia currently qualifies as a great power, mainly (or even only) because of its large nuclear arsenal. But as Mearsheimer (2019) has argued, Russia “will be by far the weakest of the three great powers for the foreseeable future, unless either the US or Chinese economy encounters major long-term problems.”

Although it has plenty of economic and soft power, the EU is not currently a great power because it lacks military capability. However, European re-armament is speeding up and in the next five to ten years, EU countries will have substantial military capacity (Burilkov et al 2025), especially if reinforced by partnerships with countries including the UK, Canada, Norway and Ukraine.

Another candidate for great power status is India, the world’s most populous country and already one of the five largest in terms of GDP, with the fastest growing economy among the top five. India has also a rapidly growing military footprint. Its 2025 defence budget was the third largest in the world, after the US and China, not counting the EU as bloc.

Middle/regional powers: in Asia (Indonesia, Japan), Africa (Nigeria, South Africa), the Middle East (Turkey, Saudi Arabia) and South America (Brazil). All these seven countries (except Nigeria) belong to the G20 and are already regional powers. Brazil, Saudi Arabia and South Africa also belong to the BRICS, as do China, India and Russia.

The three scenarios we discuss differ with respect to two variables: the degree of intensity in the US-China geopolitical rivalry; and the capacity of other major powers and smaller countries to organise rules-based international cooperation and institutions.

Note that the scenarios are not designed as a typical triad comprising a ‘central’ or ‘base case’ scenario, which represents the most likely outcome based on current information, plus upside and downside scenarios that explore more optimistic and pessimistic outcomes. Instead, they are meant to be organising principles that help describe possible states of the world in 2030-2035. Actual outcomes could well consist of weighted combinations of two of these scenarios (or even all three), and of variants within scenarios.

3.1 Scenario 1: collapse of international cooperation

Scenario 1 is defined as a ‘bad’ (collectively inefficient) non-cooperative equilibrium across the three tiers of powers. By 2030-2035, there are only loose and opportunistic alliances between countries, and a bare minimum of international cooperation. The global public goods created after the Second World War (UN, IMF, World Bank, WTO) have lost relevance or ceased to exist, mainly because of the intense geopolitical competition between the US and China, with neither willing or able to provide or promote international public goods, and both acting coercively towards other countries.

The US continues to maintain substantial tariffs, even if they have not led to the desired results (US reindustrialisation and enhanced economic security), mainly because they raise substantial revenue for the US government, which needs it to help finance its large debt.

The only global public good that continues to be provided in this scenario might be some degree of control of nuclear proliferation, the area with the biggest potential negative global externality. Another area with a very large potential negative global externality, climate change, is one of the victims of the collapse of the international order, propelled by a doom loop involving domestic and international conflict.

Major powers with low social cohesion, high public debts and high levels of support for populist politicians oppose international cooperation and institutions. Meanwhile, nationalist and populist policies reduce economic growth and the ability of countries to deal with the economic consequences of ageing and climate change (Funke et al 2023), which further increases domestic discontent and international conflicts.

Scenario 1 closely relates to the ‘Kindleberger trap’, a term coined by Joseph Nye to warn – a few weeks before the start of the first Trump presidency – of the risk of a situation in which neither the declining superpower, the US, nor the ascending one, China, is able or willing to assume the role of ‘benevolent hegemon’14.

Since Kindleberger (1973), it has been widely agreed that such a role must be played by one of the great powers to sustain a liberal international order, as the US did for the Western sphere during the Cold War period or globally during the much shorter period of hyper-globalisation15. Scenario 1 lacks any such hegemon.

3.2 Scenario 2: back to a world of blocs

The defining feature of scenario 2 is that the world splits into three groups: a US-led bloc, a China-led bloc and a non-aligned set of countries. This scenario has two variants, depending on the degree of interdependence between the US and China blocs16:

In the decoupling variant, the US-China geopolitical rivalry is intense, and after more than a decade of economic (trade, finance, technology) and political fragmentation, the two blocs are detached from one another, perhaps not as much as was the case between the western and eastern blocs during the Cold War, but far more than is the case in 202517.

In the derisking variant, the US-China geopolitical competition is somewhat less intense, and the two blocs remain fairly interdependent, managing the risks of such interdependence with “intelligent economic security policy”18. This is in line with what President Biden’s National Security Advisor, Jake Sullivan (2023), advocated with his “small yard, high fence” policy: selective decoupling in areas where national security is at stake.

The first variant is easier to understand. It amounts to a new Cold War, with little relationship between the US-led and China-led blocs, except for security issues handled by the two superpowers. The second variant is probably more realistic, though harder to grasp.

In particular, it is not clear what the exact perimeter of the ‘small yard’ would be, nor whether it would be possible to really keep it ‘small’. After all, what constitutes ‘national security’ or even ‘economic security’ is highly subjective. In addition, imports and supplier relationships that pose a risk to economic security are very hard to pinpoint empirically (Pisani-Ferry et al 2024).

In both variants, global cooperation would likely be more extensive than in scenario 1. In particular, the two blocs may agree to cooperate not only on nuclear proliferation, but also on climate change. Global economic institutions including the IMF, World Bank and the WTO would retain meaningful roles.

In the decoupling variant, however, these roles would be much reduced, even compared to their already diminished levels in 2024, ie. before the de-facto US exit from the WTO in 2025. In particular, trade governance would probably revert to the pre-WTO days, when GATT members enjoyed more ‘policy space’ (meaning they could be more protectionist) and there was no Appellate Body to adjudicate disputes, resolution of which was left to diplomats and politicians rather than judges.

This governance structure would include most current WTO members, but might not include the US, unless by 2030-2035 it has re-embraced some form of rules-based trade, particularly the most-favoured-nation (MFN) non-discrimination principle that is enshrined in Article I of the GATT and is one of its cornerstones.

With China and its state capitalist practices now impacting the US-led bloc relatively little, the countries of this bloc may decide to retain WTO-like governance among themselves, including by reinstating the Appellate Body dismantled by US actions during the Obama and first Trump administrations because of rulings related to trade with China19.

In the de-risking variant, the two blocs should in principle be ready to cooperate more closely than in the decoupling variant, and economic institutions including the IMF, World Bank and the WTO should retain greater roles, with some redefinitions to meet demands from the Global South, which would presumably remain non-aligned with the two blocs.

In terms of membership of the two blocs, it is fair to assume that countries that are likely to remain security-dependent on the US for geographical reasons, such as South Korea or Japan, will be part of the US bloc. It is less clear with which bloc the EU, India and Russia – the three actual or potential ‘great powers’ – would align.

In view of the EU’s lopsided trade deal with the US administration20, it might seem obvious that the EU has chosen, or felt that it had to choose, the US bloc. However, this was in 2025. By 2030-2035, the EU may have gained sufficient strategic autonomy to be able to make real choices, especially if European military capacities have been strengthened.

In view of India’s history since independence in 1947, during which it stayed non-aligned with both the US and the Soviet Union and later Russia, India is unlikely to align itself with the US. However, an opportunistic alliance with America to counter its Chinese neighbour is likely to remain part of its strategy.

Finally, Russia’s position is by no means obvious. It has a solid alliance with China, which has been strengthened by the war in Ukraine. However, Russia has gradually become the junior partner in its relationship with China and may seek to reestablish a more balanced relationship by strengthening links with Europe and America.

A crucial factor in the decision of the EU to align itself with, or perhaps behind, the US, or to become non-aligned, will be US behaviour. Will it return to its role of relatively benevolent hegemon, or will it continue to behave as a ‘coercive hegemon’, as it did by imposing a 15 percent reciprocal tariff on the EU and demanding from the EU concessions for not imposing higher tariffs, which has been described as humiliating?21

In the former case, the EU would likely continue to align with the US, though it would seek a better arrangement than it enjoys currently. In the latter case, it would be difficult for the EU to belong to the US-led bloc, pushing it toward the non-aligned.

3.3 Scenario 3: multilateralism reinvented

In scenario 3, the two superpowers, although remaining rivals in some areas, agree to cooperate to provide global public goods in all areas that have potential negative externalities, including nuclear proliferation, climate change, trade and finance, because they have discovered – perhaps after having passed painfully through scenarios 1 and 2 – that not tackling common problems through common efforts and institutions has a high cost, not only for others but also for themselves.

In this idealistic scenario, a new international order would be established. This would involve reforming multilateral global institutions including the UN, the IMF, World Bank and WTO to guarantee a greater role for the Global South, which remained largely non-aligned in scenario 2, and to respond better to their development goals, while ensuring international security and dealing with global warming.

This new order would not depend on the ability or willingness of a superpower to provide global public goods. Instead, the new international order would be managed by a new grouping composed of China, the United States, Brazil, the EU, India, the African Union and maybe one or two more countries. In its most idealistic variant, this new grouping would take over from China, France, Russia, the UK and US as the new permanent members of the UN Security Council.

A less idealistic, though still ambitious, variant of this scenario would assume that the US-China rivalry will preclude the participation of the two superpowers in the reinvention of the multilateral rules-based order, at least initially.

In this variant, a coalition of countries, involving the EU, the UK, Norway, Canada and a small group of like-minded countries from the Global North (including Japan and Korea) and the Global South, would take the initiative, hoping that the US will join them at a later stage. China, however, may already be part of the coalition for some issues (such as climate change) though not for others (such as trade), as we discuss in section 4.

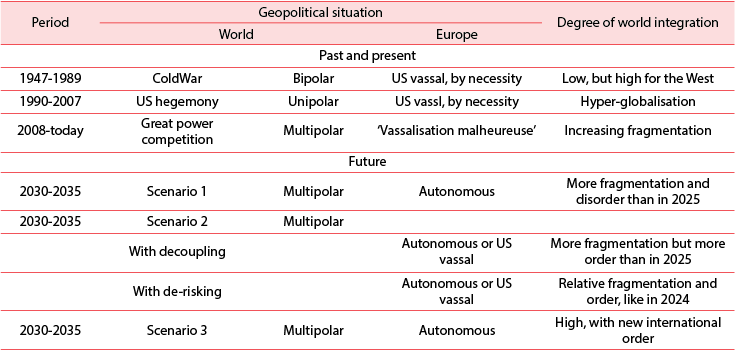

Table 1 summarises the geopolitical situation and the degree of world integration in each of the three scenarios for 2030-2035 (and beyond) and compares them to the conditions that prevailed during the three phases from 1945 to the present.

Table 1. Geopolitical situation and degree of world integration, by period

Source: Bruegel.

From the perspective of informing EU policy, the scenario analysis offers two main takeaways. First, the three scenarios can be ranked in terms of their welfare implications for the EU and the world collectively. Scenario 1 would be least desirable for the EU, most individual countries and countries collectively, because international cooperation on global public goods would be largely absent, armed conflict would likely be frequent, and protectionism would become the norm.

Scenario 2 (multipolarity with strong elements of bipolarity and some multilateralism within each of the two blocs) would be better because it would entail some international rules (strong ones inside the blocs and weaker ones between them) and greater capacity to deal with global issues than scenario 1.

Finally, scenario 3 (multipolarity with multilateralism) would be the most desirable.

Second, the probability of realisation of any of these three scenarios mostly depends on the two superpowers. But the other major powers, including the EU, will also be influential. The EU and its allies may also be able to shape which variant of a scenario becomes reality. As already indicated at the beginning of section 3, all three scenarios have two features in common: continued US-China rivalry for at least a decade, and multipolarity.

In such a setting, the EU may be able to take steps, with other partners, to push the world in the direction of scenario 3; or it may be able to shape scenario 2 by strengthening international institutions and/or by choosing whether to align with the US or be non-aligned in areas other than security (on which Europe will want to preserve NATO).

4 Policy choices for Europe

The discussion in section 3 implies that EU policy and institutional choices must serve two purposes: to influence the world in the direction of greater stability and international cooperation – that is, scenario 3, or the more benign variants of scenario 2 – and to optimally adapt to whichever scenario or scenario combination arises.

This appears to create a dilemma. However hard the EU may try to preserve or restore a cooperative international order, it may fail. If it does, it would then need a different set of institutions and policies than it would need in the case of success. Scenario 3 may justify policy choices that have the same flavour as in the period of hyper-globalisation: low levels of military spending, high levels international specialisation.

In some variants, the US might regain its status as a reliable ally, implying that depending on the US in areas such as defence, technology or digital infrastructure would have a low cost. In contrast, in one variant of scenario 2 and in scenario 1, the EU might be essentially on its own, forcing much higher levels of self-reliance. Military spending would be high, and the argument for much deeper military integration in the EU, including a common army, would be far stronger.

As it turns out, however, identifying the right policies is much simpler than this confusing array of state-contingent possibilities suggests, for two reasons.

First, many policies choices do not involve a trade-off between security and efficiency. These include all reforms that encourage innovation and deepen the single market22. Such reforms are not just good for growth, but help the economy weather shocks, including those resulting from economic coercion.

A deeper single market allows the flexible reallocation of services and goods production in the face of external shocks, while deeper and more unified capital markets reduce both financial fragility and dependence on US capital markets.

Second, Europe’s policymakers are not called on to make policy choices for 2035. They are called upon to make choices for the next one to five years, both in light of how these choices will impact Europe during this period, and how they will influence Europe’s future.

Seen in this light, a dominant strategy emerges. Apart from pursuing policies that are good for both growth and resilience – which should be done anyway – Europe should make policy choices that reduce its dependence on the two superpowers and increase its security more broadly.

This would protect it against attempts by the superpowers to exploit this dependency, and it would increase Europe’s bargaining power, both to deter bad behaviour – such as arbitrary imposition of tariffs by the US, export embargos by China or aggression by Russia – and to preserve or rebuild cooperative international arrangements.

Such policies are good both in the world as it is currently and is likely to remain in the medium term – a world in which the US is no longer a friendly hegemon. Such policies would also nudge the world in a better direction.

In the remainder of this section, we develop a short-to medium term policy agenda that meets these criteria and covers two areas: EU domestic and international policies.

4.1 The domestic policy agenda

4.1.1 Defence autonomy

An essential element of strategic autonomy is to strengthen the EU’s ability (and that of its European neighbours, including Ukraine) to defend itself without help from the United States. The EU and its European allies also have a strong interest in preserving NATO: the North Atlantic alliance has been, and continues to be, a cornerstone of its security. This requires a strategy that satisfies both objectives: preservation of NATO, and much greater defence autonomy from the US.

Over the past year, the EU has started to move in this direction, by accelerating national rearmament, and through modest steps that help members shoulder the financial burden of rearmament and that encourage joint procurement, including SAFE, a €150 billion lending instrument23, and the use of the ‘national escape clause’ (NEC) to accommodate higher defence spending under EU fiscal rules24. But these steps do not go nearly far enough. Europe needs to go much further, in two respects.

First, it must create a single market for defence equipment. This should include non-EU allies including the UK, Norway, Ukraine and potentially Canada, Switzerland and Turkey. Because such a market will be resisted by national defence-industrial interests, its creation requires a legal commitment device, analogous to EU legislation prohibiting national preferences in procurement and promoting competition within the EU.

In addition to prohibiting discrimination in procurement against companies inside the single market, such legislation should designate areas and modalities for joint procurement and lay the basis for standardisation of defence products. Europe-wide competition, greater standardisation and joint procurement (where possible) are essential to raise the scale of European defence production, reducing unit costs and ensuring the interoperability of equipment.

Unfortunately, creating such legislation through EU regulations or directives is impossible because Article 346 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the EU (TFEU) exempts national security related industry from single-market commitments.

Hence, the legal framework for creating a single European defence market requires an intergovernmental treaty, with an institutional mechanism to enforce it. One advantage of taking this route is that it would allow non-EU countries to join on an equal footing, and it would not require all EU countries to join.

Second, Europe must jointly develop and owning common defence assets to reduce its dependence on US-provided strategic enablers such as satellite-based intelligence, surveillance and communication infrastructure, strategic airlift (heavy transport aircraft and aerial refuelling systems), military mobility and air defence systems.

While NATO functions well, these can complement US-provided assets and contribute to fairer burden-sharing within the alliance. And if the US were to lose interest, Europe would have an alternative.

Assets of this type must be jointly planned and funded to ensure fair burden-sharing and good incentives. This could be done through a new intergovernmental organisation created by EU NATO members and their European allies (Wolff et al 2025; Zettelmeyer et al 2025a).

Or it could be done through existing, EU-based institutions and arrangements, with the EU providing funding through dedicated debt issuance financed by service payments by the countries that benefit from the common defence assets (Steinbach et al 2025), and planning and technical expertise through Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) and the European Defence Agency.

In either case, operational control would need to be delegated to national or joint control-and-command systems that have the military capacity to run them.

4.1.2 Tech autonomy and AI

Defence autonomy is closely related to technological and, especially today, AI-related autonomy. On this, the EU (and other countries) faces both hardware and software challenges.

In the 2030-2035 timeframe, reunification of Taiwan with China cannot be ruled out, creating a risk that the entire world’s supply of state-of-the-art 2 nanometre (or less) chips, important for AI development, will be in Chinese hands. Medium-term EU technological and AI sovereignty may rest on having such a plant not just outside Taiwan, but inside the EU or in a geographically close and politically reliable trading partner. Appropriate EU measures to sway key firm-level decisions towards meeting this goal will be necessary.

On the software side, US firms have an entrenched dominance over global digital services platforms outside the Chinese market. To successfully dislodge current technology incumbents and secure EU technological autonomy in these areas, entirely new technologies are likely to be required.

EU policies must therefore remain focused on facilitating such disruptive innovation through ‘moonshot missions’, rather than on supporting EU-based substitutes for existing services offered by US domiciled entities. This will include focusing on several policy areas, with careful consideration given to the probable impact of AI on future technology trends and on broader society.

AI is a powerfully disruptive general-purpose technology (Bresnahan and Trajtenberg 1995; Ding 2021), characterised by a wide and pervasive applicability across many economic sectors, and with the potential for continuing technical improvements and synergies with other innovations. This means skills for the promotion of AI adoption throughout the EU economy will be crucial.

This requires focusing on a wide section of the workforce, rather than just the limited segment needed to pioneer its development. Designing and training innovative AI applications at thousands of large EU firms and SMEs requires a workforce with access to practically focused AI skills, with course certifications recognised across the EU, AI based life-long learning modules and AI courses available at tertiary, professional degree and vocational training educational institutions.

Accelerating adoption by European businesses of AI assisted workflows, task solving and product development further requires flexible labour market regulation and workplace conditions that will facilitate profitable firm-level AI adoption.

AI will meanwhile continue to generate fake online identities and misinformation, frequently promoted by platform-owning intermediaries through algorithms designed to maximise their revenues. It will therefore become, and likely already is, a conduit for destabilisation and hybrid warfare.

To counter this, the EU, with private-sector identity-verification service providers in a public-private partnership to ensure cost and technology standards, should implement a common digital identity and authentication standard.

This should include a common digital EU identity platform to serve as a gateway via which Europeans will access a wide variety of public and private online services.

Working in tandem with current provisions in the Digital Markets Act (Regulation (EU) 2022/1925), the promotion of verifiable human-generated content in the EU will weaken the digital platform network effects currently fuelling the dominance of US-based entities. This will help promote European content providers and reduce the influence of robotised digital information created outside the EU.

4.1.3 Financial autonomy

European citizens, banks and firms depend heavily on the US through several financial channels. These include the payments system (the only EU-wide retail payment service providers are American companies; EU-based competing services are typically nationally based) and dependence on US Treasury Bonds as a store of value and as collateral.

In the current state of US politics, as well as in scenario 1 and some variants of scenario 2, this is a significant problem. A coercive US could threaten to order its companies to disrupt EU payments to gain leverage, impose taxes on capital outflows or even threaten to restructure US Treasury Bonds held by specific institutional holders along the lines described by Miran (2024).

The introduction of the (retail) digital euro is an important step to guard against the first risk but is not sufficient, for two reasons. First, holdings of digital euros are expected to be tightly capped to a few thousand euros. Furthermore, the digital euro will not be usable for payments outside the euro area.

While the digital euro could prove useful to consumers and for safeguarding retail payments inside the euro area, it will not reduce the dependence of EU companies on US-based payment technologies. While private European solutions are emerging25, it is unclear how reliable they will become, particularly if the providers may themselves be dependent on US technology.

Second, the expected growth of dollar-based stablecoins implies that EU dependence on the US dollar both for payments and as a store of value may be about to become a lot bigger. The US administration is promoting dollar-based stablecoins, backed by US Treasuries, for fiscal reasons. Unless there are EU-based alternatives, US stablecoins might become the payments technology of choice for EU companies, particularly for international transactions.

The EU could respond in two ways. One approach would be for the EU (including the European Central Bank) to actively support the creation of euro-based stablecoins, while ensuring their safety26. This could be done by promoting the harmonisation and standardisation of euro stablecoins, and by mitigating systemic risk, including by giving stablecoin issuers direct access to ECB liquidity support.

Second, the EU could maintain the current strategy on stablecoins, which is to provide a regulatory framework but otherwise leave the market to itself. But if this is the choice, the ECB should also provide a digital currency that can compete with stablecoins in providing free and fast payments and settlement services, both wholesale and retail. This would go far beyond the digital euro as currently planned27.

In either case, the ECB should accelerate its work on improving wholesale digital payments infrastructure, an area in which it has started a pilot project (Appia)28. This could be made interoperable with stablecoins, making euro stablecoin transactions faster and more secure and improving the attractiveness of regulated relative to unregulated stablecoins. And the EU needs to accelerate work on capital market union (rebranded the Savings and Investment Union), enabling the emergence of low-cost, diversified investment instruments available to all savers and investors (EU and non-EU).

4.1.4 Energy systems

Europe’s reliance on imported energy has proven a strategic vulnerability. Europe’s strategy of building a largely electrified energy system powered by domestic resources (European Commission 2024) is the right path to decarbonise and to end dependence on imported fossil fuels. But if the necessary investments, which are substantial, are planned and financed country-by-country, Europe risks locking in avoidably high energy costs.

A predictable, European rules-based market framework, embedded in coordinated long-term system planning, can significantly reduce investor risk and the cost of capital, prevent wasteful duplication and deliver a more efficient geographic and technological mix of generation, storage and demand.

Beyond immediate savings in dispatch and investment, a large and predictable market fosters scale economies, competition and innovation, reducing costs over time (Zachmann et al 2024). Equally, a consistent framework enhances resilience by turning Europe’s scale and diversity into cost-effective mutual insurance.

The current system is still far from a single market in which price differences point to underlying economic cost differences. The biggest successes in the last two decades have been the common carbon market and the coupling of electricity wholesale markets, which has substantially reduced inefficiencies in dispatch across borders (eg. when the wind is blowing strongly in one country, production from gas-fired power plants in another country can be reduced).

But currently, the system remains characterised by poorly coordinated national electricity system development planning, unaligned national remuneration mechanisms for investments in generation, opaque stacking of national policy-driven pricing-components, leading to idiosyncratic final electricity prices for individual consumers, and insufficient crossborder transmission and its inefficient usage.

An ambitious strategy to put the EU on track to a resilient and affordable integrated electricity system should include:

Establishment of an EU energy information administration that would providing reliable, relevant and usable data on the current and planned state of the energy system, underpinning informed policy discussions.

Introduction of real coordination of national system planning, including an independent top-down view serving as a benchmark.

A European fund to catalyse more crossborder transmission.

Progress towards a single borderless dispatch market, in which only physical constraints would justify price differences.

A means of ensuring that capacity remuneration mechanisms are organised, at least at regional level (Holmberg et al 2025).

Making this work will require long-term trust, discipline to resist domestic vested interests and a willingness to pool elements of sovereignty. It will only succeed with a credible commitment at the highest political level.

4.1.5 Secure access to critical minerals

China successfully weaponised its critical minerals export-control regime and established trade escalation dominance over the US in retaliation against Donald Trump’s tariffs29. While the EU is neither in a geopolitical rivalry nor a trade war with China, EU firms were affected by China’s export controls on critical minerals.

The urgency of securing EU access to critical minerals in the face of China’s continuing global dominance, especially of refining and processing of critical minerals, has risen since the European Critical Raw Materials Act (CRMA, Regulation (EU) 2024/1252) entered into force in May 2024. New policy measures must now be added. Domestic measures should include further incentivising and mandating critical raw materials recycling.

The recently updated EU battery material recovery targets30, applying 2031 target values of 95 percent for cobalt, copper, lead and nickel31, should serve as inspiration for all identified critical materials. Target values must be updated frequently to track progress in best commercially available recycling practices.

For rare earths that are used in such small quantities that recycling may not be cost efficient, mandatory minimum stockpiles should be established. EU governments could choose to do this at national or EU level by simply buying and stockpiling the raw materials deemed sufficiently important, or they can incentivise businesses to do it via tax benefits or prescribed firm-level inventory levels.

Significant expansion of public funding for basic materials research at EU public and private institutions, pursuing ‘innovative substitution’ to make new and cheaper but equally efficient materials available to replace critical raw materials currently sourced from China.

However, the EU should not push for domestic production targets for critical mineral extraction and processing that are costly to implement. It should rely instead on trade with trusted partners (see section 4.2).

4.1.6 A risk-based reform of the EU fiscal framework

The 2024 reform of the EU fiscal framework was a big step in the right direction. It rightly requires high-debt, high-fiscal-risk countries to cut their deficits quickly. But it also suffers from two major flaws.

The costs associated with these flaws, insofar as they guide national fiscal policies in the EU in the wrong direction, were perhaps manageable before the acceleration the geopolitical challenges the EU has faced since the start of the second Trump administration. But they have now been shown to be prohibitive, including in most of the scenarios discussed in section 3.

The first flaw, which was apparent even before the system became fully final (Darvas et al 2023) was that EU-endorsed investment spending was not favoured sufficiently relative to other spending. While debt sustainability must remain the primary objective of fiscal rules, there should be no quantitative limits on a debt-financed investment boost within a pre-agreed period (say, seven years), provided that: (1) the criteria of high-quality public investment defined in the current fiscal framework are complied with, and (2) debt remains sustainable at the end of the period.

The latter will generally require adjustment in the non-investment budget while the investment programme is being carried out. However, the adjustment needed to pay for even a large investment programme – provided it is temporary – is limited (Annex 1 of Darvas et al 2024).

The second flaw has become obvious only more recently. It is that the rules impose the same standard of fiscal adjustment – to put debt on a declining path with high probability within four to seven years – regardless of whether fiscal risks are high or low. The only exception is for countries with debt below 60 percent of GDP, which do not need to put their debt on a declining path as long as it is projected to stay below 60 percent in the medium term.

The consequence is heavy constraints on the fiscal policies of both countries with debts below but close to 60 percent of GDP, and close to but above 60 percent of GDP, even when those countries could afford an extended period of increasing debt without meaningful fiscal risks (because their debt remains relatively low and the adjustment required to stabilise the debt would remain manageable).

There may be several reasons why no-one worried about this feature of the new rules. First, it relates directly to Article 126 TFEU in conjunction with Treaty Protocol 12, which defines government deficits as excessive if debt is above the 60 percent of GDP reference value unless it “approaches the reference value at a satisfactory pace.”

Second, the countries that would benefit from greater flexibility without creating fiscal risks – including Germany and potentially the Netherlands – felt that they did not need it. In Germany, a national fiscal rule imposed even tougher constraints than the EU rule. This situation has now changed.

As a result, the EU rules are imposing constraints on German policy and potentially the policies of other countries close to the 60 percent of GDP threshold that are tighter than is good for these countries or for the EU collectively (Zettelmeyer et al 2025b).

A solution that gives more fiscal space to low-risk countries could take one of two forms (Steinbach and Zettelmeyer 2025; Pench 2025):

First, define much longer adjustment horizons for countries with debt above but near 60 percent of GDP and low fiscal risks. The latter could be identified using a sovereign risk assessment methodology (such as the IMF’s sovereign risk and debt sustainability framework, or using elements of the current EU methodology), perhaps supported by market indicators, including risk premia.

Alternatively, increase the debt reference value outlined in Treaty Protocol 12 from 60 percent to 90 percent. This would not require Treaty change, but it would require unanimity in the Council.

4.2 The international policy agenda

To enhance its strategic autonomy, making significant progress on domestic policy should be an absolute priority for the EU during the next five to ten years. Simultaneously, the EU should develop its international agenda. We focus on two areas: trade and climate.

4.2.1 Trade policy

EU trade policy should have two objectives. First, it should promote trade, thereby contributing to growth and enhanced strategic autonomy. Second, this autonomy should be used to promote a rules-based international trade order that favours gains from trade.

On the first objective, the EU needs to further extend its large network of regional and bilateral trade agreements (already currently covering 74 countries and 44 percent of EU trade)32 to enhance its economic security, including in critical raw materials.

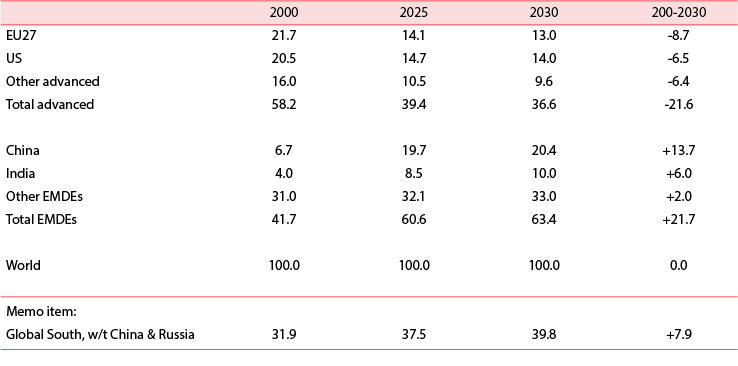

Here, the EU’s strategic emphasis should be on agreements with the Global South, which is already pivotal in many areas and can only increase in importance in the future given its growth prospects. By 2030, the Global South (defined here as the emerging and developing economies (EMDEs), minus China and Russia) is expected to account for 40 percent of global GDP at PPP, slightly more than the share of the west (defined here as the advanced economies) and double that of China (Table 2).

Table 2. The EU27 and the world: GDP at PPP (% of the world), 2000, 2025, and 2030

Source: Bruegel based on IMF (WEO).

The EU has already free-trade agreements (FTAs) with important countries in the Global South, including Mexico, South Africa and Vietnam. It should rapidly ratify the FTA with Brazil (and its Mercosur partners) and conclude FTA negotiations with India and Indonesia33, the three biggest players in the Global South.

The EU also has strategic partnerships on raw materials with 14 countries from the Global North (including Australia, Canada and Norway) and the Global South (including Argentina, Chile and Zambia), complementing existing or future FTAs. These partnerships should be welcomed but also given more resources.

On the second objective, the EU should seek to move the trading system towards our scenario 3, or at least the most benign version of scenario 2. This involves two priorities: ensuring that the EU and most economies continue to adhere to existing WTO rules, despite the Trump administration’s behaviour, and seeking effective reform of the WTO.

The EU must decide whether it is politically ready to take the lead and gather a ‘coalition of the willing’ to redesign international trade rules and institutions without US participation (at least initially). The US does not believe at the moment in a rules-based order, while China’s economic system sits oddly with the practices of most other countries.

Sweden’s National Board of Trade (Altenberg 2025) has proposed that the EU launch a rules-based trade coalition (RBTC) with like-minded partners, extending Commission President Ursula von der Leyen’s June 2025 suggestion that the EU deepen its cooperation with the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP)34. According to President von der Leyen, acting together, the EU and the CPTPP countries would show to the world that free trade with a large number of countries is possible on a rules-based foundation.

Using two main criteria to select RBTC partners – like-mindedness at the WTO, and countries with which the EU already has or is in the process of signing an FTA – Altenberg (2025) came up with non-exclusive list of 56 potential coalition members: the 27 EU countries, 13 non-EU European countries (including Iceland, Norway, Switzerland and Ukraine), 11 CPTPP members (including the UK), and five others35. Neither China not the US are on the list of potential RBTC partners (Altenberg 2025).

The coalition would operate outside the WTO institutional framework, but its ultimate goal would be to strengthen the multilateral trading system and the WTO by reforming them. At the same time, the coalition should be ready to cooperate with countries interested in maintaining a rules-based framework. This could be done through open plurilateral agreements with different memberships. For instance, an agreement to cooperate on the trade and climate interface would need to include China, India, Indonesia, Brazil and South Africa (Garcia Bercero 2025).

This and other proposals based on the idea of coalitions of the willing are compatible with scenario 3.

4.2.2 International climate policy

For climate protection, there is no option other than multi- or plurilateralism, to even hope to keep to the goals of the Paris Agreement. Ideally, plurilateral efforts would need to involve the top five emitters – China, the US, the EU, India and Russia – which together account for roughly 60 percent of global emissions, with China responsible for half this figure.

In this area, a coalition of the willing, perhaps led by the EU but leaving out China, the US and Russia, will clearly not work. Assuming that the US and Russia are unwilling to participate at the moment, the coalition would need to include the EU, China and India, and perhaps some other large emitters such as Brazil and Japan.

This coalition would account for a little more than 50 percent of global emissions but would be rather unbalanced in terms of emissions between emerging economies (with China, India and Brazil accounting together for roughly 40 percent of global emissions) and advanced economies (with the EU and Japan accounting together for only 10 percent of global emissions).